This Week's Show

Air Date: February 20, 2026

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Canceling Climate Regs

View the page for this story

After a landmark Supreme Court case that directed EPA to determine whether carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases endanger public health, the agency found in 2009 that indeed they do. Now, the Trump EPA is attempting to revoke that endangerment finding to unravel all subsequent regulations on tailpipes, smokestacks and more. Vermont Law and Graduate School emeritus Professor Pat Parenteau explains to Host Jenni Doering why this step is just the beginning of what looks to be a long legal fight. (12:13)

Stormy Weather for Climate Science

View the page for this story

The Trump administration has declared scientists at places like the National Center for Atmospheric Research are promoting ‘climate hysteria’ by overstating the risks to public health and safety, so it’s moving to cut off funds for NCAR. Former TV weatherman Alan Sealls, president of the American Meteorological Society, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the important climate and weather modeling NCAR does and how the loss of funding could impact this research. (09:24)

Ice Skating on the Rideau Canal

/ Bob CartyView the page for this story

The warmer winters of climate disruption are bringing shorter and shorter skating seasons on the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, Canada. We head into the Living on Earth archives for a taste of days gone by, when reporter Bob Carty hit the ice to meet locals enjoying the serenity of a skate along the canal. (07:18)

"Under Milkweed"

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

One of the most heavenly scents on Earth is that of milkweed in bloom, says Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender. But fewer and fewer monarch butterflies are showing up to feed and lay their eggs on this vital plant that gives them a powerful toxic defense against predators. (02:24)

Bluetooth Butterfly Tracking

View the page for this story

Monarch butterflies can travel thousands of miles each year between Mexico and North America in an epic relay race of multiple generations. And thanks to new technology, our phones and other Bluetooth devices can now tell us what paths these brave little insects take on this journey. Dan Fagin, who teaches environmental journalism at NYU and is writing a book about monarchs, talks with Host Steve Curwood about the tiny trackers and what it’s like to be among millions of monarchs where they overwinter in Mexico. (15:06)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

260220 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Dan Fagin, Pat Parenteau, Alan Sealls

REPORTERS: Bob Carty, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The Trump EPA attempts what it calls the biggest deregulatory action ever, if it survives court battles.

PARENTEAU: By repealing the endangerment finding, you're knocking out the foundation for all of the federal government's regulation of carbon pollution and greenhouse gases, whether it's oil refineries, cement plants, every source you can think of that's putting this kind of pollution into the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: Also, a breakthrough for monarch butterfly research.

FAGIN: The Holy Grail forever in monarch science has been to develop some kind of radio tagging, which can work for bigger animals, but to figure out a way to make a tag so small that we can actually track the entire journey of a monarch butterfly.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Canceling Climate Regs

The E.P.A. has moved to repeal its 2009 “endangerment finding,” which says that greenhouse gases endanger human health. (Photo: Adina Voicu, Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In the landmark 2007 case Massachusetts versus EPA, the Supreme Court ruled 5 to 4 that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases qualify as air pollutants under the Clean Air Act and should be controlled if they endanger public health. And when Barack Obama became president in 2009 the EPA found greenhouse gases do in fact endanger human health and welfare and thus need to be regulated. The EPA did not put a cap on all global warming gases, but focused on major sectors, including tailpipe emissions from vehicles, the smokestacks of power plants, and emissions from oil and gas extraction. Revoking endangerment eliminates such rules and re-ignites the conservative anti regulatory campaign that began in the Reagan era. Repeal of the endangerment finding won’t happen without fights in court, but if the Trump administration does finally win its bid to end federal climate pollution regulation, states may move to curb emissions and expand efforts like the existing regional greenhouse gas initiative. Joining us now is Pat Parenteau, emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School, and an EPA Regional Counsel under President Ronald Reagan. Pat welcome back to Living on Earth!

PARENTEAU: Thanks, Jenni, it's very good to be with you.

DOERING: Pat, what are the likely consequences of the EPA decision now to rescind this finding, the consequences for public health and the climate?

If upheld by the courts, Pat Parenteau says the repeal of the endangerment finding could result in 18 billion tons of additional pollution in the atmosphere, 58,000 additional deaths, and 37 million more asthma attacks in the United States, according to estimates from the Environmental Defense Fund. (Photo: United Nations, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PARENTEAU: The consequences cannot be overstated, and they're negative. By repealing the endangerment finding, you're knocking out the foundation for all of the federal government's regulation of carbon pollution and greenhouse gases, whether it's oil refineries, cement plants, every source you can think of that's putting this kind of pollution into the atmosphere. This removes the ability of EPA to regulate any of it. When Trump announced this repeal of the endangerment finding at his press conference, he and EPA Administrator Zeldin were bragging about the fact that this was the largest deregulatory effort in the history of the country. Right along with that, and they didn't acknowledge this, it's the most devastating decision by the federal government endangering public health and welfare in the history of the country. Here are some of the statistics. Eighteen billion tons of pollution will be in the air we breathe and in the atmosphere driving climate change as a result of this decision, if it holds, and we'll be talking about that. Fifty-eight thousand additional deaths will occur as a result of this, and those deaths will come from the effects of climate change, like heat waves, floods, fires, drought, but there's also lots of other kinds of illnesses, respiratory illnesses. There will be 37 million more asthma attacks on Americans as a result of this decision. Those are some of the health effects, but the impacts go well beyond that. They're going to increase fuel prices by an estimated 25 cents per gallon by 2035, if this holds. That can result in $1.7 trillion impacts on consumers. Again, Trump was bragging about the fact that this decision saves $1 trillion, but that's just the cost of compliance for industry. It ignores the cost of climate change.

DOERING: All right, so Pat walk us through what the Trump administration EPA has argued in this move to revoke the engagement finding. How exactly are they framing this?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so they basically are saying the United States Supreme Court got it wrong in Massachusetts versus EPA. What Zeldin is basically saying is, when I read the Clean Air Act, I don't see in it the authority, the clear delegation of authority to do what the Obama administration did and what the Biden administration built on that and did, right? So this is a frontal attack on the Supreme Court's decision in Mass versus EPA. It's pretty clear the strategy here is to get this case back to the Supreme Court and have it overrule Massachusetts versus EPA and adopt the reading of the statute that Zeldin is arguing instead. And that would have very profound consequences.

The case may ultimately reach the U.S. Supreme Court, where a decision would have long-term consequences for the E.P.A.’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Joe Ravi, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: Now, Pat in the original proposed rule to revoke the endangerment finding, the Trump EPA seemed to be focusing a little bit on climate denial, on denying the science itself, but I understand that they have really walked that back in this more final rule. So talk to me about that aspect of this.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, I mean, they're basically saying science doesn't matter because we're saying we don't have the legal authority to do anything about it. It's, well, it's too bad if, in fact, the science is accurate, because we can't do anything about it. So they have totally shifted the focus. Zeldin has, wisely, I would say, decided, I'm not going to attack the science, which is rock solid. But then when you think about it, so you're admitting that there's a danger. You're not denying there's a danger. You're saying you can't do anything about it? That's what he's doing.

DOERING: So Pat. How solid are the legal grounds of this action by EPA? I mean, to what extent can they simply rescind this landmark finding in a single action?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, well, they can't do it by themselves. You know, I've worked up three scenarios for you, okay? So there are lots of different ways this could go. The first scenario is, it's not clear that this case can even get to the Supreme Court before the clock runs out on the Trump administration, right? He's got less than three years to go. This case will be ripe, as we say, for litigation. It goes to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, what we call the DC Circuit. It's a very expert court. It's also a court that isn't dominated by conservatives. So the question is, can Trump and Zeldin manage to get through the DC Circuit and up to the Supreme Court before, as I would put it, they turn into a pumpkin at the end of their term? I think there's a 50/50 chance it won't get there in time. The reason that's significant is because if the next president, which we can only hope to God, shows more of an understanding of the threat of climate change and more of a commitment to do something about it, they could reinstate, they could repeal the repeal, and they could reinstate the endangerment finding. So you see the incredible significance of the clock right now. If Trump can't get this to the Supreme Court and win in the Supreme Court before he's done, the next president can erase all of this.

DOERING: So that's scenario one. What's the second scenario, Pat?

Our guest Pat Parenteau predicts that the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, or the DC Circuit, may issue a “stay” or pause of implementation of the repeal of the endangerment finding if requested. (Photo: Tony Webster, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

PARENTEAU: The second scenario, then, is Trump does get the thing to the Supreme Court before he's done, but he loses, okay? He loses five to four, the same way George W Bush lost five to four in Mass versus EPA. How does that happen, right? Well, this is a head count exercise. You start with the three liberal so-called justices, what I call the three sisters, right? You got to have their votes, but it's pretty clear you do have their votes to uphold Massachusetts versus EPA. And you know, the Trump administration is counting on Chief Justice Roberts being in their corner, but subsequently, the Chief Justice has said, I think Massachusetts versus EPA is settled law, so you don't have his vote going in. So then you go down the list, you know you're going to get Justice Thomas, Justice Alito and probably Justice Gorsuch. You're probably going to get Justice Kavanaugh, because Justice Kavanaugh has been very critical of EPA regulation under the Clean Air Act in the past. So there's four votes. Where does the fifth vote come from? It comes down to Justice Barrett. So I think she's the swing vote in this case, if it gets there, and I think from a decision that she rendered in a very important Clean Water Act case, I think she's going to have trouble seeing that if the science says this is a danger, if the Supreme Court, 19 years ago, said that EPA had the authority to regulate it, I don't think she's going to say, overrule it. So that's why I think there's a 60 to 40 chance if it gets to the Supreme Court in time, Trump loses.

DOERING: All right, so what's the third scenario?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so the third scenario, if you're still with me, is Trump wins in the Supreme Court, God forbid, in my view, but I have to acknowledge that's definitely a possibility, right? If that happens, then a future president can't do anything about it. That's the significance of that. Once the Supreme Court has ruled, EPA no longer has the authority to regulate greenhouse gases. Only Congress can reinstate that authority. A future president is hamstrung. Can't do anything about it.

DOERING: So Pat, just to clarify, has the endangerment finding actually been revoked by this action by EPA, or does that not happen until the legal battles have been settled?

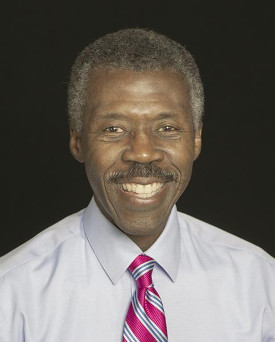

Pat Parenteau served as an EPA regional counsel under President Ronald Reagan and he’s currently an emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. (Photo: Vermont Law and Graduate School)

PARENTEAU: Oh, no, it does happen. Technically, here's what happens. The rule is published in the Federal Register, and then 60 days later, the repeal of the tailpipe standards takes effect, okay? So we're still in a two-month window right now, but when that takes effect, it's automatic. So here's what I predict is going to happen in response to that. The Attorneys General of California and Massachusetts have already announced, no surprise, they're going to challenge this, and I predict that the first thing they're going to do in the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia is to move for what we call a "stay," okay, of the rule, which means put a pause on the rule while the case works its way out. I think they have a very strong case to do that. Think about it, this decision overturns again 19 years of regulation. It proposes to overturn a Supreme Court decision that's already on the books. The point is, the District of Columbia court is going to say, I think it's going to say, a stay of this rule is entirely appropriate. Given all of that, what's the hurry? That's a long-winded answer, but it means that the rule will take effect unless the DC Circuit puts a stay on it.

DOERING: So it sounds like this is really just the beginning of the process of repealing this finding.

PARENTEAU: I would say so, and that's why I say I think it's going to take longer than three years to sort it out.

DOERING: Pat Parenteau served as EPA Regional Council under President Ronald Reagan, and he's currently an emeritus professor at Vermont Law and Graduate School. Thanks again so much, Pat.

PARENTEAU: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- The White House | “Final Rule: Rescission of the Greenhouse Gas Endangerment Finding and Motor Vehicle Greenhouse Gas Emission Standards Under the Clean Air Act”

- Heritage Foundation | "Heritage Praises Trump Administration Rollback of Endangerment Finding"

- Sierra Magazine | "Environmental Groups Vow to Stop Trump’s EPA From Revoking the Endangerment Finding As global heating accelerates, the nation’s environmental watchdog is trying to muzzle its own ability to act"

- Learn more about Pat Parenteau

- The New York Times | “E.P.A. Faces First Lawsuit Over Its Killing of Major Climate Rule”

- Environmental Defense Fund | "Weakening Climate Protections will Increase Pollution, Cost Americans More than a Trillion Dollars"

[MUSIC: The String Revolution, “Englishman in New York” on Red Drops, 934555 Records DK]

CURWOOD: Coming up, Stormy weather for an important climate center. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Waverley Street Foundation, working to cultivate a healing planet with community-led programs for better food, healthy farmlands, and smarter building, energy and businesses.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Edgar Meyer, Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007: I. Prélude, on Bach: Unaccompanied Cello Suites Performed on Double Bass by Johann Sebastian Bach, Sony Classical]

Stormy Weather for Climate Science

The National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. (Photo: Thomson M, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The Trump White House has declared scientists at places like the National Center for Atmospheric Research or NCAR are promoting climate hysteria by overstating the risks to public health and safety. So, citing what he calls “climate alarmism,” White House Budget director Russ Vought says he has ordered the National Science Foundation to cut off funds for NCAR, which is based in Boulder, Colorado. Alan Sealls is a former TV weatherman who teaches meteorology at the University of South Alabama and serves as president of the American Meteorological Society. Welcome to Living on Earth, Alan!

SEALLS: Thank you. Happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So many Americans, I dare say that most, aren't familiar with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, or NCAR, yet it plays a central role in weather and climate research in the United States and around the world, indeed. Describe for us what exactly NCAR does.

SEALLS: Yeah. So NCAR, National Center for Atmospheric Research, what it does is in the name. It is the center for our nation's research into the atmospheric science. A lot of folks right now, if they look at their weather app on their phone, the computer model that they're seeing on the phone either directly came from NCAR or it was a base model that's public domain, that was built upon by private companies to improve it and make it more detailed and more local. So in the most basic sense for meteorologists, NCAR has come up with all sorts of incredible assets that we use to model weather, predict the weather. They've come up with tools that the hurricane hunters use when they're in a hurricane to drop into the storm and get more detailed measurements, which statistically improves the forecast. NCAR has come up with methods to reduce aircraft turbulence, which not only makes it more comfortable for the passengers, but it makes it more cost effective for the airlines to avoid the turbulence. It extends the life of, literally, the airplanes. And NCAR definitely is known for climate research. What NCAR has done over the decades is allowed climate scientists to figure out that, yes, fossil fuels create carbon dioxide, which, yes, does create sort of a barrier to allow heat to be trapped in the earth, which is what we call climate change. So things like that, that's what NCAR helps us better understand. And we're not done yet. It is a nonstop process to gain more knowledge and share that knowledge with the world.

CURWOOD: NCAR is not a government agency exactly. What is it?

SEALLS: So it's really interesting. NCAR was started by the National Science Foundation, which is a government agency. And that started about 1950. Ten years later, NCAR was put together as a consortium of universities that said, we can't afford to have our own computers, but we need them to do research. We can't afford to have our own aircraft, but we need aircraft to do our own research. So NCAR is sort of a central repository of not only data, but resources, equipment, brain power that universities can tap into to do their research.

The National Science Foundation will be breaking up the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado. This facility is one of the largest sources of climate alarmism in the country. A comprehensive review is underway & any vital activities such as weather…

— Russ Vought (@russvought) December 17, 2025

CURWOOD: So the White House has suggested that NCAR's responsibilities could be simply relocated to other organizations. At the same time, though, the Trump administration has significantly reduced funding for several science agencies, including the National Science Foundation itself. So given these cuts, to what extent do you think other institutions have the capacity to take on NCAR's work?

SEALLS: So I think the duties that NCAR has could be moved around, and still, the overall product would be the same. But the question is, why? Why would you take something, in my opinion, that's working really well, and take it apart? And I will add that recently, the budgets for NASA, NOAA, USGS, other government agencies, those budgets were finalized in a bill which, the cuts were nowhere near as severe as the White House Office of Management and Budget originally intended. They were not too far off the mark from last year's budget. But the problem is, NCAR is not listed in the budget, which means, in a sense, it already on paper, has disappeared. So now we're at the crossroads of, what do we do? How do we rebuild or reorganize? I don't think anyone is sure the best way to do it. And that brings us to where we are at this point, which is the National Science Foundation put out a notice called the DCL, Dear Colleague Letter, and the Dear Colleague Letter goes out to the entire industry and the world, and it says, what's your input? What do you think we can do to move what was NCAR in a different direction?

CURWOOD: So you are president of the American Meteorological Society, and you had an annual meeting at the end of January. So what's the overall mood, the sentiment within your colleagues regarding these proposed changes to the National Center for Atmospheric Research?

NCAR’s two research aircraft are among the world’s most advanced tools for gathering atmospheric data. Sealls worries that private industry may take over these capabilities, resulting in a less equitable spread of data for all. (Photo: National Science Foundation, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

SEALLS: It was a mixed feeling. We actually had a town hall session specific to what was going on at NCAR, and it was a packed house, hundreds of people, and almost all those people in one form or another, had either worked with NCAR, at NCAR, or received the benefit of NCAR. And as you would imagine, people were, they weren't surprised, but no one was happy about what was going on. And it was really more questions about, how do we go forward, rather than people saying, oh, we need to hold on to what was. Because it's pretty obvious right now that NCAR will not be allowed to be what it was. So within the American Meteorological Society, we are trying to get all of our members to give us input, so that we can give input to the National Science Foundation. But a large part of our membership is private industry. So for example, NCAR maintains two research aircraft. It doesn't specify, what should we do with this aircraft or these aircraft, but the letter does say, what do you think we can do to replace that capability? Private industry could say, hey, we've got aircraft. We can do this research. Some of that I find a little bit odd, because private industry is all about competition with other businesses, whereas NCAR is about collaboration and sharing on on an equal level. And that is one of the strengths of a government funded agency, is that everybody benefits equally.

CURWOOD: This isn't the first pushback by the federal government against climate and meteorological research. Some folks have said that we're behind in building weather satellites that can help us observe Earth's systems. What's your view of that?

SEALLS: So in weather technology, there is always research where we say, here's the latest, greatest tool that we need to replace our current tools. And that requires funding, government funding. It requires research. And the latest round of satellite technology, there are some sensors that could go on the satellite that right now, the government is not funding for them to go there. It's available. The hardware is there. The technology is there. But the government is saying, well, we don't think that part is important. Sometimes, because that part happens to be associated with climate which right now is associated with something negative, but that's really short-sighted.

Sealls emphasizes the importance of weather satellites for forecasting and tracking storms, adding that sustained government funding is required to update and maintain this technology. (Photo: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what are the risks that we face when it comes to weather forecasting and disaster preparedness without a fully functioning NCAR?

SEALLS: I'll tell you what it's not first, because sometimes people jump to the most gloom and doom projection. It's not going to say that tomorrow's weather forecast is going to be bad or less accurate, but what it does say is two or three years from now, the forecast may not be any more accurate than it is this year. NCAR has allowed steady progress in forecasting weather. And it means that if we lose NCAR and its capabilities, we will start lagging behind other countries as a nation. And again, the capabilities go into our communication and electrical power. When we have our big storms, those are the two things that we often lose. So it's about being able to better predict, which means better prepare and be less vulnerable to the extremes of weather.

Alan Sealls is a broadcast meteorologist, author, and professor of weather broadcasting at the University of South Alabama. He’s also the current president of the American Meteorological Society. (Photo: Courtesy of Alan Sealls)

CURWOOD: So let's look ahead now. What do you expect the next few months to hold for NCAR as an organization, do you think?

SEALLS: Uncertainty, unfortunately. One of the points that I picked up at our American Meteorological Society conference, when I talked to folks in the private weather industry, they said, we can't make decisions because there's no certainty, and that means they can't invest. Another company that makes radars, for example, says the parts, we have to pay more because of the tariffs. So the uncertainty right now feeds into the bigger picture of our communities. The Dear Colleague Letter that we talked about, coming from the National Science Foundation, in theory, it should help the National Science Foundation say, oh, we have found these really good solutions to what we can do after NCAR is gone. But we don't know that they're going to follow that. We would hope that they do, but we don't know. So unfortunately, uncertainty.

CURWOOD: Alan Sealls is a broadcast meteorologist, author and professor of weather broadcasting at the University of South Alabama. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

SEALLS: Thank you.

Related links:

- About the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR)

- Read the National Science Foundation’s Dear Colleague Letter

- Learn more about Alan Sealls

[MUSIC: David Grier, “Angeline The Baker” on Freewheeling, Rounder Records, a Division of Concord Music Group, Inc.]

Ice Skating on the Rideau Canal

Winterlude Festival on the canal in Ottawa (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

DOERING: One of the many casualties of climate disruption and weird winter weather is the Rideau Canal in downtown Ottawa, Canada, which can no longer count on becoming a skateway every winter. But this year the January cold blasting out of the Arctic had people gliding on the canal for 41 straight days, so today we reprise a 2013 piece when veteran broadcaster Bob Carty hit the ice.

[TRAFFIC COMMUTE]

[RADIO ANNOUNCER: “CURRENTLY IN OTTAWA IT’S AROUND 16 DEGREES...]

CARTY: Rush hour in Ottawa on a cold March morning. So cold you have to scrape the frost off the inside of the car windows. So cold your tires have frozen flat on the bottom, and until they warm up you get a bumpy ride, what Canadians call having square tires. And then there's the slippery streets, the snowbanks, and the slush.

[RADIO ANNOUNCER: “...AND ANOTHER ACCIDENT. WE’RE UP TO 6 NOW...”]

CARTY: In Ottawa, where winter is a five-month affair, there is at least an alternative to the morning madness of rush hour. Instead of the expressway, you can take the skateway.

[PHONE RINGS]

[RECORDED VOICE: “RIDEAU CANAL CONDITIONS AT 8:30 A.M. THE ICE SURFACE CONDITIONS ARE GOOD FROM THE NATIONAL ARTS CENTER TO PATTERSON CREEK...”]

[SKATES ON ICE]

MAN 1: Early in the morning, when the sun comes up, and there's hardly anybody on the canal and you can just hear your skates, it's about the only thing you can hear. It's wonderful.

WOMAN 1: I haven't skated for years. I skated when I was a kid, and it's great to be able to skate again, and it's just so much fun skating to work. I just think it's incredible. This frozen Rideau Canal is like a wonder of the world.

Winterlude Festival on the canal in Ottawa (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CARTY: For two-and-a-half months, from late December to the usual mid-March thaw, an old canal running through Ottawa becomes the world's largest skating rink. It's 15 yards wide in most places. On one side students head south towards the University. On the other side, some neighbors and I are heading downtown with backpacks and briefcases. It's a three-and-a-half-mile commute for me, a 20-minute skate on a good day.

MAN 2: There's a few little bumps, but otherwise it's just really smooth and clear. The best part would be just at the beginning here, when you're sort of on the ice, just between the two walls of the canal.

WOMAN 2: What's interesting for me, being able to look at the sides of the canal, is that my ancestors were Irish stone masons who were brought over to work on the canal. The canal was built by Colonel By in 1832, and it was to give Canadians a route so they could avoid being ambushed by Americans on the St. Lawrence River. It's an amazing engineering feat.

CARTY: And there's another engineering feat just in keeping the skateway in operation every day. It takes 40 full-time employees, and a fleet of snow blowers, plows, and tractor-mounted sweepers, to clean off the snow and the ice shavings. Then, every other night, workers drill holes through the ice to pump up water to flood the surface. It's the equivalent of flooding 125 end-to-end hockey rinks. It takes eight hours. The result is a clean, smooth surface. Almost. You do have to watch out for the occasional rut. And the choice of skates is critical.

WOMAN 3: This took me a long time to get it straight about what kind of skates. I tried the new plastic molded skates that have Velcro snaps, and they're supposed to be really quick to put on. But I hated the feel of them. Then I tried the traditional women's fancy skates with the picks. Didn't like them, and so I now am the proud owner of my first pair of men's hockey skates, and they're great.

CARTY: Hockey skates are my choice, too. Though the new fad on the skateway are speed skates, the ones with long 14-inch blades, worn by men and women in spandex outfits who torque by you as you're struggling against the headwind. [GASPS] Did I mention the wind? It can turn a pleasant, just below freezing temperature into a wind chill that feels like 15 degrees below zero. Doesn't seem to bother some skateway commuters, though I have a personal rule of thumb: If your nostril hair freezes in the first minute, maybe it's too cold to skate today, even if you do have the appropriate apparel, such as some or all of the following.

WOMAN 4: Scarves and a “toque,” mitts, long underwear.

MAN 3: Fairly light shell jacket and a sweater. Shirt and tie. And the trick is not to get too sweaty on the way to work.

WOMAN 5: I, for one, need knee pads. [LAUGHS]

WOMAN 6: As you can see, I got on a really ugly hat that keeps me warm. And you need Kleenex in your pocket.

WOMAN 7: You need to have Kleenex in your pocket for two reasons. One, you need to be able to blow your nose, because it gets cold and then you go into the warmth. The second reason is to wipe off your skate blades when you're finished.

[CHILDREN TALKING, SKATING]

CARTY: After the morning rush hour, the skateway is taken over by others - children and their teachers on a school outing, pairs of mothers, on skates, pushing strollers, reckless teenagers bobbing in between tentative tourists who are trying not to break any bones.

[SKATES SWOOSHING]

WOMAN 8: The amazing thing is, on a beautiful Saturday or Sunday, to see thousands and thousands of people on this canal walking, pushing their kids in these little sleighs. And you see people who are new to Canada, who are valiantly trying to skate and kind of staggering along, and it's great.

[SKATING ON ICE]

Ottawa skaters (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CARTY: At the end of the day, the commuters reappear on the skateway, a bit rubbery in the legs. Which sometimes requires a brief stop for rest and refreshment at one of the outdoor eateries on the canal.

CLERK AT COUNTER: How are you? What can I get for you?

CUSTOMER: One orange juice, one hot chocolate, and a famous beaver tail.

CARTY: Yes, you heard it right. He ordered a beaver tail. What exactly is a beaver tail?

CUSTOMER 2: It's really a flat, long, dough-like pastry thing, and this one has garlic butter and cheese on it, so it's almost like a mini-pizza. But you can get just plain cinnamon and sugar, and even if you want some jams on top, you can do that, too.

[SKATES ON ICE]

CARTY: Recharged and refreshed, the final mile home is like skating downhill. The wind is gone. The stars are coming out. Skateway commuters can give you sound ecological arguments for doing this: it saves fossil fuels, it reduces pollution, it lessens the risk of climate change. But frankly, the real reason is that it just feels good. As one 7-year-old put it, you don't have to go around in circles. It's fun to skate straight. For Living on Earth, I'm Bob Carty, skating straight on the Rideau Canal in Ottawa, Canada.

[MUSIC: Paul Winter “Wolf Eyes” from Common ground (A&M Records 1977)]

DOERING: We first aired this piece back in 2013. The following year Bob Carty passed away after an award-winning career with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and he also produced many fine stories for Living on Earth. We miss him and his great gifts in audio and reporting.

Related links:

- Ottawa Citizen | “Big void left by the closure of the Rideau Canal Skateway”

- CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) remembers Bob Carty

- More about Bob Carty and his music

[MUSIC: Paul Winter “Wolf Eyes” from Common ground (A&M Records 1977)]

"Under Milkweed"

A female monarch butterfly feeds from a milkweed plant. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Monarch butterflies and the milkweed they depend on inspired this essay from Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Under Milkweed

Monarch Butterfly

Stewart B. McKinney National Wildlife Refuge

© 2026 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

LENDER: When milkweed is in bloom I love to be in the middle. “Weed” must have meant something else when our Celtic-Anglo-Saxon-Norse-French-Roman tongue acquired the name and named it, because milkweed is beautiful when it blooms. Compound blossoms. Carmine violet. Each flowerlet a cup of nectar the scent of ambrosia... Do not give in to the temptation, to eat of it, or drink of it. Milkweed can stop your beating heart. Maybe that’s why the nomenclature is what it is. Never mind. Milkweed is not there for us. Milkweed brings monarch butterflies. Who feed on the sweets and the poison too. That black-orange-yellow-fluttering-butterfly of a monarch’s wings tells bird, and beast alike, take a bite and it is me, who will finish, you!

Last year and the year before and for a number of years before that by the time the monarchs arrived milkweed had gone to seed. This year the same, all the monarchs too late. Except one. One monarch butterfly who came to the right place, for milkweed, in flower, just in time.

A male monarch butterfly at rest. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Spring is around the corner now. Nothing is certain. Maybe that one monarch will tell her friends. Maybe, I’ll just… help her out. Under milkweed, as milkweed blooms, at the top of my lungs “Heh! Monarch Butterflies! Over heeeere!”

One monarch butterfly is only magic. Two? A miracle. Which is exactly, what butterflies are about. And so is Life. And so are you.

Related link:

Mark Seth Lender’s Website

[MUSIC: Jacob Shea, Sara Barone, Bastille, “Monarch Butterflies” on Planet Earth III (Original Television Soundtrack)]

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence, Mark Seth Lender. Just ahead, tracking the three-thousand-mile journey of that small but mighty butterfly. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the estate of Rosamund Stone Zander - celebrated painter, environmentalist, and author of The Art of Possibility – who inspired others to see the profound interconnectedness of all living things, and to act with courage and creativity on behalf of our planet. Support also comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Scarborough Fair” on Pure Hammered Dulcimer, Traditional, arranged Joshua Messick]

Bluetooth Butterfly Tracking

Tags from Cellular Tracking Technologies of Cape May, New Jersey, allow scientists and butterfly enthusiasts to follow the journey of monarch butterflies as they fly south for the winter. (Photo: Sheldon Blackshire)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The amazing Monarch butterfly is as beautiful as it is mysterious. Every year successive generations of monarchs take part in an epic relay, with each generation playing a different but vital role. Monarch butterflies that hatch in the spring and early summer live fast and die young at only two to six weeks. But those that emerge in late summer can survive six to nine months. That’s long enough to migrate thousands of miles south for the winter and start the return north the following spring to breed. The precise paths these brave little insects take to get from North America to their winter colonies in Mexico have long eluded scientists and butterfly enthusiasts. But thanks to new technology, our phones and other Bluetooth devices can now tell us where these tiny creatures are traveling. Joining us now is Dan Fagin, who teaches environmental journalism at NYU and is writing a book about monarchs. Dan, welcome back to Living on Earth!

FAGIN: Thanks, Steve, nice to talk to you.

CURWOOD: And great to talk to you. Hey, let's talk monarch butterflies. Monarchs have this fascinating migration pattern. Several generations they fly north, and then one generation to get all the way back to the tropics. Please talk to me about the new way to track them.

FAGIN: Yeah, something really kind of amazing has happened to monarch science. And you know, monarch butterflies are this beloved butterfly that scientists have been studying intently, really, since the 1940s and you know, the most intriguing thing about them, they have a lot of intriguing habits, but the most intriguing thing, Steve, as you mentioned, is this amazing migration that they do, multiple generations, thousands of miles. And for a long time, people have been trying to understand where monarchs go and how they get there. And for many, many years, the only way that they could do that was by using paper tags or sticker tags. The Holy Grail forever in monarch science has been to develop some kind of radio tagging, which can work for bigger animals, but to figure out a way to make a tag so small that we can actually track the entire journey of a monarch butterfly. And sure enough, after all these years, a startup company called Cellular Tracking Technologies based in Cape May, New Jersey, figured out a way to do it, and now we know where these monarchs are actually going and how they get there.

CURWOOD: So what are some of the surprising places that monarch butterflies go?

Dan Fagin, director of New York University’s Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and the author of the Pulitzer Prize winning Toms River, is writing a book about monarch butterflies. (Photo: Dan Fagin)

FAGIN: Maybe the most amazing thing about how this technology works is that a monarch pings, they register if they pass within a couple hundred feet of any kind of device equipped with Bluetooth, whether that person realizes it or not, if their Bluetooth is turned on, they are helping with this data collection. So we can now see, Steve, that if a monarch is over the ocean and passes near a boat that has a cellular device turned onto Bluetooth, they will ping. And sure enough, some of these monarch tracks, which, by the way, people can see for themselves by downloading the app, pass over oceans, deserts, all kinds of unexpected places.

CURWOOD: Let me understand this for sure, the monarch tracking device transmits in Bluetooth, and anyone gets that signal, you have to have the app to get the signal? Where is the signal going?

FAGIN: No, anyone can contribute to the data set, whether they realize they're doing it or not. Their device will ping and the data will go back to the central data depository that will show up as one detection along the route. Anyone can see where these tagged monarchs are going by downloading the app and looking. That's not about detecting the presence of monarchs. That's about looking at the data that's already been collected.

CURWOOD: Talk to me for a moment more about the technology. I mean, how much does a monarch butterfly weigh and how much does this tracking device weigh? I imagine the numbers are small in both cases, huh?

FAGIN: Yeah, really small. The way I like to analogize it is, a butterfly weighs about as much as half of a raisin, so it's very light, and the tags themselves are much lighter, still, little more than 10 percent of the body weight of the monarch, which is sort of like three uncooked grains of rice riding on half of a raisin.

CURWOOD: So Dan, what are we learning about the monarchs by tracking them? What are we learning about them through this tracking?

FAGIN: Yeah, a lot of things. You know, the monarch, you know, for reasons that we can talk about, is in trouble. We know that their populations are declining, especially the migratory population, they face all kinds of problems. So it's really important to figure out, well, how do we know what are the most popular routes that they take? And so we can think about how to help them in those particular places, and now we have a better idea about that, and after another few years of radio tagging, we'll have a better idea still. And another thing, Steve, is we can tell how affected by weather they are, because you can watch what happens to one of these monarchs when a big cold front comes by or there's a storm, and we can now see in real time that these monarchs are getting blown way off course. So now we know that weather is a very, very big deal for these guys. That they're stronger than we think, but they're not strong enough to resist a huge storm. But the flip side of that is they have these fantastic navigational abilities.

Tracking devices are about 10 percent of the weight of the monarch butterfly, the equivalent of three uncooked grains of rice on half a raisin, according to Dan Fagin, who is writing a book about monarch butterflies. (Photo: Sheldon Blackshire)

CURWOOD: How do they navigate? How do they know where they're going?

FAGIN: Yeah, it's really quite amazing, Steve. Over millions of years, they've evolved two different biocompasses, and they need two, because one of them tracks the sun is sort of anchored to the sun, but that's a problem when it's cloudy out. So they also have another biocompass that is attuned to the Earth's magnetic field. And you know, there's so many amazing things about this that they have these abilities at all. But what's especially amazing is that the sun compass actually compensates for the sun's journey across the sky, at least as we perceive it. We're the ones who are moving, not the sun, but as we perceive it. That could be a real problem for monarchs. If they just track the sun, they would constantly go off course. But this bio compass they have adjusts for this. It's called the time compensated sun compass, and it's quite miraculous. A few other insects have them too.

CURWOOD: Uh huh. Wait a second, you're telling me that monarchs can tell time essentially.

FAGIN: Yeah, they can. They can. You know, they they have a much more naturalistic way of doing it. They don't look at digits, but yeah, they adjust based on where the sun is and where south, or sometimes southwest, is their general journey direction in the fall. And they adjust for that all day long, and it keeps them going. So even when they're blown way off course, by these storms, they can adjust and get back on track, and this new data shows us this.

Digital tags on monarch butterflies ping off Bluetooth devices and send back data to scientists to map the path of monarch butterflies as they journey south for the winter. Data has shown that cold fronts and storms blow monarchs off course, but their navigational skills help them reach their overwintering place. (Photo: Courtesy of Cape May Point Arts and Science Center)

CURWOOD: So talking about the southern journey that single generation monarch might make, say from eastern Canada all the way to Mexico, I'm guessing most of them don't make it all the way. So how is climate disruption and loss of habitat making things harder for them? What's the survival rate?

FAGIN: Some people think that, you know, less than 5 percent of the monarchs that start the journey in September actually make it through the winter and then reproduce successfully in the early spring. That it's less than 5 percent. Some people think it's a little higher than that. That it might be, you know, more like 10 or 15 percent. These new tags will help us figure that out, once we get a nice, big, robust data set. But they face so many potential risks along the journey, and really at every stage of their year-long multi-generational life cycle. Climate change is an obvious one, because climate change creates problems for them at every stage of their yearly journey. They definitely when they're migrating in the fall, they need access to nectar plants, or they'll never make it. They need to fortify themselves along the way, and climate change is wreaking some havoc with where and when these plants are available in the fall and also in the spring, when they're moving north and they need nectar plants, again. In Mexico, climate change is creating all sorts of problems for them. They have a very narrow temperature range that they are comfortable with and that means that for winter, that's why they migrate in the first place. And for winter, they need to find a place that's not too cold and not too hot. And it turns out that's a few Mexican mountaintops, typically around 10 or 11,000 feet high. And the problem is that as the climate gets warmer and moisture patterns change and drier, the monarch colonies on these mountains keep moving up, and essentially they're going to run out of mountainside. It's going to get too warm, and they're already, I can see, just from my own journeys, the trips I've taken down there over the last 10 years, we can see the monarchs moving up the mountain and, and they're running out of mountain. So that's a problem. There's also problem that things are getting much drier all along their journey, including in Mexico, and that has caused all kinds of disease problems in Mexico. Beetles, beetle infestations are a really big problem on their overwintering grounds. So this is a problem. And honestly, Steve, you know, climate change is only one of the big issues that they face. There are other critical problems too.

As tagged monarch butterflies travel south for the winter, they ping off Bluetooth devices such as cellphones, which send the data to scientists tracking the monarchs’ journey. The data set shows where the monarchs are located at a point in time. (Photo: Project Monarch Collaboration)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I imagine we use a lot of chemicals that aren't good for insects.

FAGIN: Yeah.

CURWOOD: And I imagine that the habitat is not exactly expanding.

FAGIN: Yeah, that's definitely true. There's a lot of recent research about neonic pesticides, neonicotinoid pesticides, that suggest they're a real problem for monarchs as well as other insects, but the biggest problem that affects them during the summertime is that monarchs coevolved with milkweed plants. They will only lay eggs on milkweeds. And it turns out that in their main summer breeding grounds, which is the upper Midwest, it coincides with the Corn Belt, with the huge corn and soybean raising areas of the Midwest. And anybody can tell you who is familiar with farming in the Midwest, something has changed fundamentally with the way that corn and soybeans are raised over the last 25 years, and that is the rise of genetically engineered seeds that are resistant to herbicides, which means that you can use a lot more herbicide, Roundup, Glyphosate is the most famous one on your crops, and that has wiped out the most important refuges of milkweeds in the upper Midwest. There's still milkweed in the Upper Midwest, but there's so much less than there used to be. And this is a big problem for monarchs.

CURWOOD: Now you've visited the tropical or perhaps subtropical monarch butterfly colonies. Talk to me about this experience. What is it like?

The Project Monarch Butterfly App allows users to see the path taken by monarch butterflies as they fly south. (Screenshot: Andrew Skerritt)

FAGIN: There's really no phenomenon quite like it on Earth. You go to these very isolated locations, in Michoacán and the State of Mexico, where there have been overwintering colonies most years, and you're already pretty high elevation. And then you start walking even higher in these park areas, and you're walking up the mountain, and you start to see more and more monarchs. And then after, you know, another half hour, 40 minutes, depending on where you are, you're hiking and hiking, you're getting tired, and then all of a sudden, you just see teeming hordes of Monarch butterflies circling overhead and in the fir trees, by the millions. It's just impossible to describe how many there are.

CURWOOD: So Dan, tell us about your interest in monarch butterflies. Where did the fascination begin?

FAGIN: Well, I think it was two different things. After I finished my last book, you know, I was very proud of that book, but it was about an emotionally difficult topic, children with cancer, and I wanted to do something different, and I was really just starting to realize that this concept of a human dominated planet is even bigger than climate change itself. Climate change is just one manifestation of this bigger question of humans essentially taking control of the future of this planet. We're living in uncontrolled experiments, and we don't know how it will end. So I was really interested in that. And then right about that same time, I had read stories about monarchs, and a neighbor was raising monarchs, and I just started to learn more. And then we decided, hey, let's put some milkweeds on the front lawn. And we waited and waited, and then monarch showed up. And it was amazing. It was such an enchanting, amazing thing. And so on a very human level, my wife and I really loved it. But it also got us thinking about, what exactly are we doing here? Are we creating? Is this a natural environment? Not really. We're creating an environment that's optimized for this species. And to me, that is a really interesting thing to think about, because it's really the future that we will all face, and our footprint is all over this planet, and there's no going back. And so as an environmental journalist, this is really the central question, and that is, what are we going to do with our power? So this is a Pottery Barn situation. We broke it and we own it, right? You break it, you buy it, and, and, and we own this planet. And so the question is, can we manage it in a way that meets human needs and also maximizes biodiversity? This is a, you know, a big question that our kids and our grandkids are going to face in all sorts of different ways. And as an environmental journalist, I want to encourage that conversation.

Each fall monarch butterflies fatten up on roadside weeds ahead of their fall migration south. A monarch feasts on dandelions along the road in Tallahassee, Florida, which is on the path toward the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: Andrew Skerritt)

CURWOOD: Pulitzer Prize winner Dan Fagin is a journalism professor at New York University, where he directs the Science, Health and Environmental reporting program, and he's working on a book about monarch butterflies that both he and his editor are waiting anxiously for. Dan Fagin, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

FAGIN: It was a pleasure talking to you, Steve.

Related links:

- Dan Fagin’s Website

- Cellular Tracking Technologies | “Revolutionary Tracking Study Follows Monarch Butterflies from Canada to Mexico Using Groundbreaking Technology and Continent-wide Collaboration”

- Find the Project Monarch Science App on the Apple Store

- Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve

[MUSIC: Jacob Shea, Sara Barone, Bastille, “Monarch Butterflies” on Planet Earth III (Original Television Soundtrack)]

DOERING: Please join us for our next Living on Earth Book Club event on Thursday, February 26th! Acclaimed nature writer and New York Times bestselling author Terry Tempest Williams will join us on Zoom to discuss her new book, The Glorians: Visitations from the Holy Ordinary, and you can be part of the conversation. So, join us online for this free event, Thursday, February 26th at 6:30 pm Eastern. Sign up now at LOE dot org slash events! That's LOE dot org slash events.

[MUSIC: Jacob Shea, Sara Barone, Bastille, “Monarch Butterflies” on Planet Earth III (Original Television Soundtrack)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Sophie Bokor, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti Mclean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Bella Smith, Julia Vaz, El Wilson, and Hedy Yang.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to the Stewart B McKinney National Wildlife Refuge. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us please, on our Facebook page, Living on Earth. Find us on Instagram, Threads and BlueSky @livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments@ loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth