January 10, 2025

Air Date: January 10, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Wildfires Bring 'Climate Trauma'

View the page for this story

Wildfires like those hitting southern California take an enormous social and psychological toll on victims and observers alike. Jyoti Mishra is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego and joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how people and communities can heal from the ‘climate trauma’ brought by wildfires and other disasters linked to the climate crisis. (09:42)

U.S. To Abdicate Climate Lead Again

View the page for this story

President-elect Trump’s stated plans to again remove the U.S. from the Paris Accord would be just the latest whiplash in a decades-long trend of U.S. inconsistency on the climate. E3G senior consultant Alden Meyer and Host Jenni Doering talk about what’s ahead for global and domestic climate policy over the next four years. (10:43)

States Fight Plastics Crisis in Court

View the page for this story

With a global plastics treaty delayed and federal action to stem the plastics crisis unlikely in the near future, states and cities are turning to the courts for remedies. Bethany Davis Noll teaches at NYU law school and joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran to explain the potential impact of these lawsuits against fossil fuel companies and beverage makers. (10:25)

Jimmy Carter's Green Legacy

View the page for this story

The Carter Presidency left a legacy of environmental action, ranging from major habitat protection to trying to address the then largely unrecognized threat of fossil fuels to climate stability. Gus Speth chaired the White House Council on Environmental Quality under Jimmy Carter and sat down with Host Steve Curwood to recall pivotal moments and ponder what might have been if the solar-panel-loving President had won a second term. (16:22)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

250110 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Bethany Davis Noll, Alden Meyer, Jyoti Mishra, Gus Speth

THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Disastrous wildfires can take a huge social and psychological toll.

MISHRA: It’s not just PTSD, it’s not just depression or anxiety, you see these cognitive effects and brain effects. The terminology is now understood as climate trauma, and it deserves its own recognition, awareness, and characterization.

DOERING: Also, the Carter White House is remembered for its prophetic message about climate change.

CARTER: The problem with the climate issue has always been that if you wait until the effects become unignorable you will have waited too long to deal with the problem. So, it's always been a question of trusting science to lead us in the right directions rather than waiting on all the consequences to come forward.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth, stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Wildfires Bring 'Climate Trauma'

The 2018 Camp Fire was California's deadliest and most destructive wildfire to date, burning over 153,000 acres and destroying nearly 19,000 structures, including the town of Paradise. Located in Northern California’s Butte County, it is approximately 500 miles north of the recent wildfires affecting Southern California and the Los Angeles region. (Photo: Pierre Marcuse, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

[FIRE SOUND – BBC https://www.tiktok.com/@bbcnews/video/7457940962195574049?is_from_webapp=1&web_id=7457962656554550827 ]

DOERING: The catastrophic wildfires that have hit Southern California are acute symptoms of the climate emergency. Climate disruption is driving rapid oscillation between massive rainstorms that promote underbrush, followed by periods of drought that dry that underbrush into tinder for wind-driven sparks. Not only are people hurt and property destroyed, the huge wildfires also sear communities and the mental health of both victims and observers. Jyoti Mishra is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego. She and colleagues from California State University, Chico studied the psychological and social impacts of the 2018 Camp Fire, California’s deadliest to that date, as well as the devastating 2023 Maui blazes.

MISHRA: Wildfires are climate disasters that we're seeing with increasing frequency in the world that we live in today and these can really, deeply impact mental health. In our work, we've shown that communities suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder symptoms, also anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms even you know, many months after witnessing a climate disaster, and it can be so prevalent that up to 30 to 40% of community members can be suffering from these mental health symptoms.

DOERING: Wow, that's a huge toll. What about the cognitive impact? How do our brains react to these disasters?

The Orange County Airport wildfire, also known as the "Airport Fire," began on September 10, 2024. It affected areas in Orange and Riverside counties and rapidly spread to over 19,000 acres with no containment reported initially. The fire disrupted air travel and blanketed nearby communities with heavy smoke, highlighting the region's growing wildfire challenges. (Photo: Daniel Lincoln, Unsplash)

MISHRA: There are definitely cognitive impacts observed not just in people who are directly exposed to the fires, but also to those who are indirectly exposed. So the difference between these individuals is that directly exposed are those who have suffered from loss of property or immediate impacts on their own family, whereas indirectly exposed individuals are those who have witnessed the fires in their community, in their immediate community, but have been fortunate to not have personal loss of any kind. We see that there can be cognitive impacts in both of these exposed individuals, whether directly exposed or indirectly exposed. The cognitive impacts can be poor ability to suppress distractions or ignore distractions in our environment, and therefore not being able to pay attention very well. This also then impacts how we make decisions, and underlying this, we find that our brains, especially the frontal cortex, which is responsible for executing all of our cognitive functions, that is hyper aroused. It is in a state of hyperactivity all the time, which is interpreted as if our brains are in this hyper alert state where everything in the environment could be threatening to us. And so imagine being in the state of someone who thinks that everything around them is a threat to their survival, then our brains are constantly computing that information, and it makes for a very tiresome effort and not being able to function very well cognitively.

DOERING: Yeah and I've heard people describe that cognitive arousal, that like hyper, anxious, aroused state, as just feeling like you can't turn your brain off and it's hard to sleep, right?

Wildfires have been intensifying in recent years as climate disruption worsens. This photo shows an aerial view of wildfires burning across California, between Joshua Tree and Los Angeles, in 2020. (Photo: Patrick Campanale, Unsplash)

MISHRA: Correct. Yes, we find a lot of sleep disturbances as part of this symptom you know, characteristics. Overall it's such a complex set of symptoms, it's not just PTSD, it's not just depression or anxiety. You see these cognitive effects and brain effects that the terminology is now understood as climate trauma. And it's its own beast that we now want to study on its own and deserves its own sort of recognition, awareness and characterization. Not just in the scientific literature, but also for our healthcare workers, our physicians, to know that when our communities are impacted by climate trauma, what kind of effects does it have on mental health and brain function and then provide appropriate treatments.

DOERING: What factors into how people can recover from a traumatic wildfire event?

MISHRA: Yes, I think several factors are important. Obviously, when one has greater means for recovery, when one has greater socioeconomics, then that can help towards rapid recovery. When one has greater healthcare access, then that helps in rapid recovery. Also having our health care physicians, our mental health care practitioners, recognize that there is this impact on our brains, on our mental health and well being, that climate trauma is a distinct entity that comes up after a climate disaster. Having that recognition and then getting proper treatment for that can make a big difference in resolution of that trauma. Having said that, we've also found that there are individual differences beyond one's means, such as for individuals who are physically fit, individuals who practice mindfulness. And then we also find that individuals who have a sense of stronger family ties and community ties, they also have lower symptom profiles.

DOERING: And you mentioned that mindfulness can actually be a part of this. Why is that?

"The Little Brain" by Dr. Jyoti Mishra was published in 2022 by Fulton Books. The book is tied to a meaningful cause, as all proceeds support Dr. Mishra's brain health research. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jyoti)

MISHRA: Well, we find the way mindfulness helps is that it helps you to compartmentalize the present moment. That you're in this present moment now and then when the fire is over, you are in a new moment and that new moment is not threatening anymore, and that you do not have to dwell in that prior moment. What happens is that our brains get stuck in that prior moment of being in the state of constant arousal that everything is threatening. Of course, everything is threatening when you are in the midst of a climate disaster, but when things are back to safety, then our brains need to understand that we're back in a safe place, and that's something that mindfulness can help with.

DOERING: Even in the midst of these disasters, we see people jumping in, trying to help out, you know, street vendors giving away food, people offering shelter in their homes for those who are fleeing fires. And then, of course, there's rebuilding that people pitch in for. What benefits can those kinds of activities bring for mental health in the wake of these disasters?

MISHRA: I think that's absolutely beneficial. Therapies that focus on psychological healing and mindfulness, compassion-based healing that are actually very effective, they work in this umbrella where one is able to look beyond oneself and embrace common humanity and be empathetic and compassionate towards common humanity, and that then brings well-being to oneself. And so I definitely recommend people to be part of these community efforts.

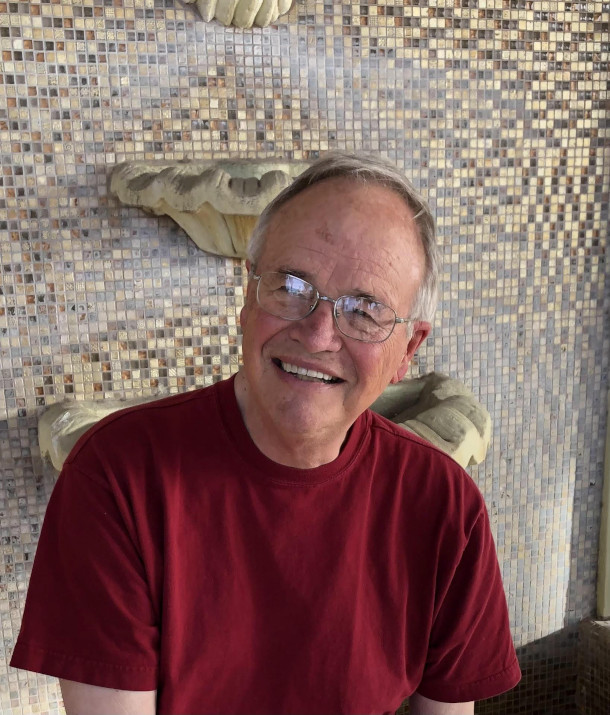

A professional headshot of Dr. Jyoti Mishra, Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego. Dr. Mishra is also the founder of the Neural Engineering and Translational Labs (NEATLabs), where she leads research on mental health. (Photo: Courtesy of Dr. Jyoti)

DOERING: Jyoti, you're based in San Diego, not too far from the Los Angeles area wildfires. And of course, San Diego itself is no stranger to fires like these. How do you feel?

MISHRA: Um, I feel. Um…just give me one moment… Sorry. I have family here from LA, sorry.

DOERING: I'm so sorry.

MISHRA: Okay, I feel deep sense of emotion and sense of, a lot of grief for our families and our community members who have lost their homes or have suffered in these climate disasters, and it only helps to, us to continue to do the work that we do, and move towards working with our community partners to develop resiliency solutions, especially for our future generations, for our children. It's important that we move away from framework of doom and gloom to how together we can survive and thrive in this new world that we live in on Earth. We are facing difficult times, but if we work together, there's still time to bend the curve, to slow the warming and to witness a world where the number of disasters that are seen are reduced over time and we need our policy makers and our politicians, everyone to work together with us on this, but it really just increases our resolve to continue to do this work.

DOERING: Jyoti Mishra is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego. Thank you so much, Jyoti.

MISHRA: Thank you. It was nice talking to you.

Related links:

- Dr. Jyoti Mishra is co author of the 2023 paper “Differences in interference processing and frontal brain function with climate trauma from California’s deadliest wildfire”

- Access detailed reports and resources on California’s wildfires, including incident updates and prevention efforts

- Inside Climate News | "As Wildfires Threaten Urban Areas Like Los Angeles, ‘Planning for the Unprecedented’ Is Crucial, Experts Say"

- Discover insights into how climate change drives the increasing severity of wildfires, based on California’s Climate Change Assessments

- Learn more about Dr. Jyoti Mishra

- Explore the work of the Neural Engineering and Translational Labs

[MUSIC: Javier Rubio Carballo “Scarborough Fair]

CURWOOD: The outlook for international climate action as the White House changes hands. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Javier Rubio Carballo “Scarborough Fair]

U.S. To Abdicate Climate Lead Again

In 2017, then-President Donald Trump announced his decision to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement. (Photo: Joyce N. Boghosian, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The California wildfires and the unprecedented hurricanes on the Gulf coast back in 2024 can be seen as climate wake-up calls. But saving the world’s forests and transforming energy systems are tremendous tasks, and more than 30 years of UN climate talks have yet to contain the continuing slide into climate disruption. The most powerful country in the world is a big part of the problem. As the US prepares to inaugurate a president who appears dismissive about the climate crisis, we’re joined by Alden Meyer to help us understand this moment and how we got here. He is a senior consultant with E3G and a longtime observer of the UN climate meetings. Hey, Alden, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MEYER: Good to be with you again. Happy New Year.

DOERING: Happy New Year. So, as the U.S. enters a second term with President Trump, he's pledged to once again remove us from the Paris Agreement. What's the history of the U.S. involvement in the underlying U.N. climate treaty?

MEYER: Well, it's kind of been a roller coaster ride for the world since this process started back in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro at the Earth Summit. President George H. W. Bush, at the time said the American way of life is not negotiable, and blocked any attempt to make commitments in that treaty for developed countries legally binding. And then, of course, five years later, we negotiated the Kyoto Protocol because the original treaty with its non-binding goals, wasn't achieving the results people wanted. And the U.S. had no strategy to ratify that treaty in the Senate under the Clinton-Gore administration. And of course, when George W. Bush became president in 2001, he famously declared that the Kyoto Protocol was dead. The rest of the world said, George, not so fast. You're not the decider here. We have a say in this, and they rallied to go ahead with Kyoto without the U.S. Fast forward to Trump's first term. Six months into his first term, he decided he would withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, which he did, and he's made very clear that he will withdraw the U.S. from Paris again, not six months into his term, but on day one. So it's kind of a roller coaster ride for the world. They're getting a little tired of it, but they have seen this movie before, and they are now figuring out how to adjust to it.

Then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry (center) holds his granddaughter, Isabelle Dobbs-Higginson on his lap while he signs the Agreement in 2016. (Photo: U.S. Department of State, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: Right. And of course, President-elect Trump may be able to say, on day one, I'm taking us out of the Paris Agreement again. When does it actually go into effect?

MEYER: Well, it would take effect one year after the formal withdrawal. But of course, it would mean that the U.S. would presumably make no efforts to meet its existing obligations under Paris, which include the 2030 commitment to cut emissions by 50 to 52% below 2005 levels, and the new commitment that the Biden administration made just last month for 2035 to make further reductions. Presumably the Trump administration would say, even though we're still in the Paris Agreement, we have no intention of taking actions to meet those commitments. It would also mean, presumably, that they would not try to meet the financial pledges that President Biden has made. He succeeded in nearly quadrupling U.S. contributions for developing country mitigation and adaptation investments over his four-year term. I think it's fair to say that we can expect President Trump will try to reverse that and either zero out or dramatically slash U.S. climate finance.

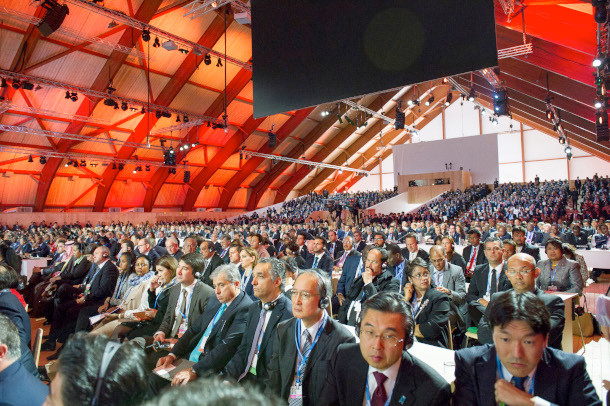

195 parties, currently including the United States, are signatories to the Paris Climate Agreement. Even after the U.S. was withdrawn from the Accord by then-President Donald Trump, no country followed in dropping out. (Photo: United Nations, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Now, as you mentioned just recently, in December, the U.S. filed an updated pledge under the Paris Accord, now calling for a 61% to 66% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2035 compared to those in 2005. What was the point of this update, Alden, knowing that we're heading towards being pulled back out of Paris?

MEYER: Well, I think the point was to show the world what our goal should be under Paris. Frankly, we think it probably should have been a little bit higher than that in terms of our fair share of reductions. But even getting to that 61 to 66% reduction, if it had been a Harris administration, would not have been that easy. It would have taken an all-out effort. But clearly, with President Trump vowing to roll back all the commitments that President Obama and President Biden put in place, domestically, it's almost certain that we will not achieve that goal and probably won't achieve the 50 to 52% goal for 2030 either. But it did set a standard for what the U.S. ought to be doing. It created kind of a North Star for the states, the cities, the governors, mayors, business leaders and others that have vowed to press ahead with emission reduction efforts despite what President-elect Trump may do, and it provides a base, of course, for the administration that comes after President Trump. Because, of course, this is a 2035 target, and six of those 10 years will be under a new president taking office in 2029. Of course, we don't know whether that next president will maintain President Trump's anti-climate ambition stance on policy, or whether they will go back to the climate leadership role that Presidents Obama and Biden tried to play.

Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate at E3G working on US and international climate policy and politics. He is a Principal at Performance Partners, which provides a range of consulting services to clients in government, business, and the non-profit sector. (Photo: Courtesy of Alden Meyer)

DOERING: Alden, what do you think domestic climate policy is going to look like when the U.S. is no longer in the Paris Agreement? And how do you think it's going to compare to President Trump's first term?

MEYER: Well, at the federal level, I think it'll pretty much be a replay of the first term in terms of rolling back regulatory action at the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, other agencies slashing funding. Of course, scientists in the federal government are concerned about possible assaults on scientific research and reporting and publications. So that could be a replay. The new factor here is the Inflation Reduction Act, which was one of the signature achievements of President Biden. On that front, it's clear that the Trump administration and President-elect Trump won't try to ramp up funding under that in terms of spending for climate justice programs, for just transition programs and other areas. But the centerpiece of that law, of course, was the tax incentives for clean technology, and the fact that the bulk of the investment spurred by those tax incentives have been going into Republican states, I think, will make it very difficult for President-elect Trump to convince even the Republican-controlled Senate and House to roll back those tax incentives. And of course, we're two or three years into that program now, and there's an argument to be made you shouldn't change the rules of the game for companies that have made investments based on those incentives. So I think those will survive. Estimates are that those could amount to a trillion dollars or more over the 10 year period they're good for. So that is already having a tremendous effect on investments in electric vehicle technology, batteries, solar, wind, other clean technologies, hydrogen, even nuclear power is benefiting from that, carbon capture investments, which has the oil industry engaged. So I think it's going to be very hard for them to roll back that. But if you look outside of Washington, the bulk of activity in terms of energy planning, transportation planning, building codes, other activities happens not at the federal government, but at states, cities, regional governments. And I think that will continue and may even ramp up.

DOERING: From what you've seen, how is the rest of the world reacting to this roller coaster of the U.S. being in the Paris Agreement and then being pulled out and being back in, time and again?

MEYER: Well, the last time President Trump pulled the U.S. out of Paris, not a single country followed us out the door. I expect that to be the case again. There was some flurry late last year that Argentina, President Milei of Argentina might be considering also leaving Paris, but he was convinced not to do that. The real question, I think, will be, is there any impact of this on the level of ambition that countries set in their next round of commitments under Paris? Because the one that the US made last month under President Biden was relatively early in the process. Most of the major players have yet to submit their 2035 emission reduction targets. And there are, of course, forces in some of these countries, China, India, Brazil, Europe, others that will argue that if the world's largest economy and second-largest emitter after China is not taking action, why should we? But of course, that's a false argument, because both it's in their own interest to reduce emissions to protect their people from the impact of climate change, and also it means they have a leg up in the race for the clean technology markets of the future. And the smarter leaders and business and investors understand that, that there's going to be huge, multi trillion-dollar markets for clean technology, and if the US steps off the playing field, that means more for the rest of us. So I think you're going to see that play out.

DOERING: Alden, which nations do you anticipate might take the lead on climate as the US steps back?

MEYER: There's a lot of expectations that the European Union and China will need to step up more on this, without the U.S.. The United Kingdom has been a leader under its new government, putting in a very ambitious commitment for 2035 at the end of last year, during the Baku Climate Summit. Other countries will be important, such as India, Indonesia, South Africa, some of the other big developing countries, and we'll see how that plays out. But most of the focus is on the EU and China. Can they reach agreement on ways to move this whole regime forward? Diplomatically, I think it also depends on what President Trump does in other areas after he takes office. Does he impose tariffs on imports? Does he try to abrogate agreements with other countries on clean energy technology research and deployment? There's a whole series of diplomatic agreements outside of the UNFCCC and the annual climate summits. That's also very important here, and we really don't have many signals yet about what his administration will do on that front.

DOERING: Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate of E3G. As always, Alden, thank you so much for taking the time with us.

MEYER: Good to talk with you, Jenni.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | "Biden Sets Higher U.S. Goal Under the Climate Pact That Trump Aims to Abandon"

- Environmental Health News | "EU Braces for Climate Challenges as Trump Eyes Paris Agreement Withdrawal"

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, “What About Me?” on We Like It Here, GroundUP Music LLC]

States Fight Plastics Crisis in Court

Some states are suing brands by claiming their products create a public nuisance. (Photo: Deishini Mariam, Wikimedia Commons, CC0)

CURWOOD: At the end of 2024, negotiations to create a global plastics treaty were suspended until mid 2025 after nations failed to reach a consensus. Meanwhile a tidal wave of plastic production just keeps on surging forward. And in the US, the incoming Trump administration has promised to roll back many environmental regulations intended to support national solutions to the plastics crisis. But many cities and states in the US are not waiting for federal and international action on plastic pollution and are seeking remedies in the courts. Bethany Davis Noll teaches at NYU law school and tracks plastics litigation. She joined Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran.

BELTRAN: So let's talk about some of the state-level lawsuits that are trying to tackle plastic pollution. What are some of the major cases to watch, and what kinds of legal arguments are they using here?

DAVIS NOLL: There's a category of cases that has to do with public nuisance, where we've seen counties and states bring claims against like a brand for creating a public nuisance. And what that generally means is, under public nuisance law, if somebody has harmed your health or your safety or your property in a way that creates a public nuisance, you can sue under these state common law doctrines. So New York State brought one of those. They've sued Pepsi. And then there's two pending at the county level in LA County and Ford County. And those basically allege that plastic pollution has harmed people's enjoyment of the environment and harmed their health. That's public nuisance. That's a state level claim. There's also deceptive practices claims. So what I mean by that is states have been suing different manufacturers for having lied to us about their products. And in that bucket, there's two different kinds of cases. One category of case I'd call greenwashing, and in that one, you see states suing brands for having claimed something about their product that's not true. You know, for example, there are two cases, one out of Connecticut and one out of Minnesota, where they sued Hefty for these bags that Hefty said were recycling bags, but really aren't, they really, actually gum up the works at the recycling facility. So those are green washing cases. The bag says recycling, and that's not true. That's what the argument is. Then there's another category of case, which is exemplified by California's recent lawsuit against Exxon. And that case is about Exxon having allegedly engaged in lying about plastics recyclability, having promoted recycling and advanced recycling as a solution for years and years. I mean, those are three big categories of cases that states are bringing: greenwashing, deceptive practices, and then public nuisance.

BELTRAN: Now Bethany, we know that exposure to microplastics and the chemicals that are used in plastics increases the risk of a wide range of health issues, from cancer to infertility. So to what extent are those health harms being used as legal grounds to go after these companies? You know, how hard is it to make that connection?

The State of California under the direction of Attorney General Rob Bonta has sued Exxon, alleging the company misled the public by promoting what it calls “advanced” recycling as a viable solution to the plastics crisis. (Photo: Harrison Keely, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

DAVIS NOLL: Yeah, I've noticed that the health harms are coming up in case after case. Starting in 2018, we looked at the cases in a tracker that we keep at NYU, and they've, the health harms have been coming up. It's not yet the case that it's the basis of a claim, you know, you harmed me with this toxic pollutant when I ate it, or something like that, something direct. But the health harms are being raised in these cases, and there's a lot of toxins that are part of the additives that gets added to the plastic that's being made. So all plastic is a polymer, and then there's an additive, and the additive is often something where we know a lot about it, like we know that thing, if we put it in our bodies, is toxic, and so we have a lot of information about the toxins that are part of plastic. But the problem is, when it becomes a micro plastic and we start eating it, unintentionally, obviously, it's broken down, and you don't know exactly which toxin or how many you consumed, and so it's harder to test. And so we just don't have sort of the really precise testing that you normally have when you're testing PFAS, for example, on PFAS' impact on somebody's body. But the evidence is coming out more and more.

BELTRAN: What do you see as the strongest legal strategy here? You know, what cases might have the potential to really set a precedent for challenging the plastic industry?

DAVIS NOLL: Well, there's a lot of strategies that I think are at play that all have different strengths. And one that I just wanted to highlight was sort of this state level claim about unfair and deceptive practices. And something to just note there is that every state has one of these laws that outlaws unfair and deceptive practices and basically tells companies not to lie to us. And they're really strong. They basically give state AGs a lot of power to go after these practices. Like, for example, Connecticut's Unfair and Deceptive Practices Act is really strong. It also has the potential for really significant damages. So it's a strong tool, and it's something to pay attention to as state AGs start using that tool on this issue.

Plastic contains many chemicals that have been linked to a wide range of health issues, from infertility to cancer. (Photo: Radulf del Maresme, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: To what extent has this kind of state litigation against big companies been successful in the past?

DAVIS NOLL: You know, one thing that's happened over time when we face a problem like this as a country is we've seen states and state AGs step up and try to do something about it. They have a variety of powers that include lawsuits, that include litigation, that include the bully pulpit, where they could send a letter, you know, asking a company to explain its practices, and that might be enough to change corporate behavior. They can do public education, they can just use a wide range of tools to address a problem, and we've seen them now start acting on this question of plastics. And what's happened in the past is we've seen that make a difference nationally. So for example, like the famous story is tobacco, right? So tobacco was, there were health harms that people were suffering from, and what they were facing was, you know, lies about how it wasn't harmful, how it didn't hurt our health. And also, you know, the marketing to teenagers and kids and so on. And there were attempts in Congress that were failing, there were also private plaintiffs who were bringing lawsuits. Those were not going well. And then eventually the state AGs started to sue, and that's when things turned around. And those were the first thing that found success against the tobacco industry. And after you saw these State AG lawsuits start, we got a huge settlement, we got change in the industry, and we got action out of Congress to face these harmful impacts and to face the lies and to stop it. So that's what I think we're at the beginning of here with plastics.

Lawsuits brought forward by state Attorneys General helped hold the tobacco industry accountable for its deceptive practices. (Photo: AnonymousEditor95, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

BELTRAN: Now besides litigation, states can also turn to legislation for action. What are examples of laws that states have been able to pass to curb plastic pollution?

DAVIS NOLL: Yeah, another big area that states are looking at in order to curb pollution is a category of legislation that's called extended producer responsibility laws, and those basically require the producer of the product to put money into recovering it and recycling it. Extended producer responsibility laws can be very useful for making sure that producers internalize the cost of the waste that you know you and I would otherwise bear. And those have been passed in Maine, Minnesota, California, and there's one pending in New York that's a really great example of what these should and can look like, and it'll be debated again in the next legislative session with which starts in January.

BELTRAN: So many of the lawsuits that we've discussed focus mostly on waste management. How much of a difference can these cases make in facing the root of the plastic crisis?

DAVIS NOLL: Yeah. I mean, I think the root of the plastics problem is production. We have enough plastic in this country. We don't need more of it, and the production facilities are harming, in really extreme ways, the people who live next door. So another category of case that's happening a lot is sort of frontline advocates challenging the production of plastic, of petrochemicals. And those cases are about the impacts of those facilities on the neighbors, and that has to do with the air pollution, that has to do with the toxins that come right out of the plant and land on the people that live nearby, and those have really well known cancer causing harms, those toxins, and the cases are about, you know that plant shouldn't be permitted because it's going to cause an additional burden on me as a community member, or you didn't analyze the impacts of this facility on the water adequately. There's a whole bunch of permitting fights that have been happening in Louisiana and elsewhere over these plants.

Bethany Davis Noll is Executive Director of the State Energy and Environmental Impact Center at the NYU School of Law and an adjunct professor at NYU. She also runs the NYU Plastics Litigation Tracker. (Photo: Courtesy of Bethany Davis Noll)

BELTRAN: And before you go Bethany, if these lawsuits do ultimately move forward, what will the consequences be for plastic producing companies nationally and internationally?

DAVIS NOLL: I guess, if the lawsuits move forward, and there's such a variety of lawsuits that I think we can count on them moving forward, the companies will have to start really taking seriously what they tell us about, what's recyclable, what isn't recyclable, I can see them starting to invest in programs that use less toxic materials to make plastic. You know, there are some things that we need that are plastic, and we could make those things with fewer toxic materials or non-toxic materials. That is something that we know how to do. So I can see companies start investing in that. It's a business opportunity for them to invest in that and into reuse programs. So I can see, you know, the more accountability and the more truth that we can get out of the industry, the more we'll see them invest in things that really are safer for us, and I can see that happening as a result of the pressure from these lawsuits.

CURWOOD: That’s Bethany Davis Noll, Executive Director of the State Energy and Environmental Impact Center at the NYU School of Law, speaking with Living on Earth’s Paloma Beltran. ExxonMobil is now pushing back with a lawsuit of its own against the California Attorney General and a coalition of environmental groups, alleging that their legal action is a “smear campaign.” Exxon is also using the countersuit to double down on its so-called advanced recycling claims. A statement by Exxon is on the Living on Earth website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- NYU Plastics Litigation Tracker

- California Globe story about EXXON suing California AG and NGOs for defamation regarding plastics

- Exxon’s complaint

- Office of the Attorney General | “Attorney General Bonta Sues ExxonMobil for Deceiving the Public on Recyclability of Plastic Products”

- Reuters | “PepsiCo Beats New York State’s Lawsuit Over Plastic Pollution”

- Sustainable Packaging | “Guide to EPR Proposals”

[MUSIC: Ry Cooder, “Great Dream From Heaven? on Into the Purple Valley, by Joseph Spence, Reprise Records]

DOERING: Just ahead – a top environmental advisor to President Carter joins us to remember his legacy. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ry Cooder, “Great Dream From Heaven? on Into the Purple Valley, by Joseph Spence, Reprise Records]

Jimmy Carter's Green Legacy

Gus Speth (left) served as a member and then Chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality during President Jimmy Carter’s (right) term from 1977-1981. (Photo: The White House, courtesy of Gus Speth)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

When Jimmy Carter passed away at the age of 100, he left behind a legacy of service and human rights advocacy in his post-presidential years. But his time in the White House also left a legacy of environmental action, ranging from major habitat protection to trying to address the then largely unrecognized threat of fossil fuels to climate stability. Through all of the Carter years, Gus Speth served on the White House Council on Environmental Quality, and he joins us from South Carolina to recall Jimmy Carter and those days. Gus, welcome back to Living on Earth!

SPETH: It's so good to hear you again, Steve, and to know that this great program continues on, strong as ever.

CURWOOD: Thank you. So Gus, you had the opportunity to work directly with the late president, Jimmy Carter, who just passed away at 100 years old. Talk to me about what it was like to be a member and then Chair of the Council on Environmental Quality in that White House.

SPETH: Serving him in the White House, as I did for four years, was such a privilege, because I had this deeper admiration for him as a person, as a man of great integrity and foresight and intelligence then, a man of science. I appreciated those things. And so I started out as a member of the Council on Environmental Quality, and our job for those four years was to help the President develop and implement an environmental program. And it took us in some very interesting directions, because it turned out to be a four years in which energy issues really pushed to the forefront in America. They've stayed there ever since. But we really began and we also became aware of the climate issue during that period.

CURWOOD: Shortly after Jimmy Carter came into office, his science advisor, Frank Press, wrote a memo about climate change. Talk to us about that memo, and what you thought of it and what happened as a result of it.

Gus Speth presents a gift to President Carter in honor of his work on Alaska Lands. (Photo: The White House, courtesy of Gus Speth)

SPETH: Well, I think this was the first time a senior official in the administration wrote directly to the President on the climate issue, to President Carter, and it was pointed, a memo about this need that to begin to incorporate the climate issue into energy policy, and at that time, the country really didn't have an energy policy to put climate into. So Carter didn't take it up right away as a separate issue, but began what turned out to be four intensive years of developing an energy policy which featured, importantly, major programs in energy efficiency and conservation and also in renewable energy, the first programs of that type. Later, our Council on Environmental Quality began to issue its own public reports on the seriousness of the climate problem. And in 1980 he gave a speech in which he, he said very plainly that the climate issue was going to be a preeminent environmental concern, and he would take it up in a second environmental decade.

CURWOOD: Yeah, which did not happen, as we all know. You know, one of the things that Frank Press wrote in that memo was, quote, "The urgency of the problem derives from our inability to shift rapidly to non fossil fuel sources once the climatic effects become evident not long after the year 2000. The situation could grow out of control before alternate energy sources and other remedial actions become effective."

SPETH: The problem with the climate issue has always been that if you wait until the effects become unignorable, you will have waited too long to deal with the problem. So it's always been a question of trusting science to lead us in the right directions, rather than waiting on all the consequences to come forward. And that was the point that Frank Press and we and others were making to the President, and it was an important point, because it's still true today. We are seeing big effects of climate change today, but the biggest effects are those that are projected to happen by science, and we need to trust that science.

CURWOOD: Now, looking back to the 1970s, what was the impact of his establishment of the Solar Energy Research Institute? What difference has that decision made in coming from then to the present time?

President Carter introduced historic energy policies during his term including the National Energy Act of 1978, promoting renewable sources and energy conservation. (Photo: National Archive and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

SPETH: Congress had actually authorized SERI, as it was called, but it was Jimmy Carter who breathed life into it and went out to Colorado and opened it up, so to speak, put a wonderful, aggressive solar energy advocate in charge of it, Dennis Hayes, and at that time, established a national goal of moving to 20% renewable energy by 2000, which is an amazing thing for the President to do at that time. I take some pride in that number because we had just earlier issued a report from the Council on Environmental Quality calling for a dramatic shift to renewable energy, and it urged the President, in this report to move the country in this report to move to a goal of 25% renewable by the year 2000. As we were, we felt like we had done an important thing when he announced 20%. That was close enough to what we had hoped for. So he was attentive to what his environmental advisors said, and I always appreciated that, and I appreciated the decency with which he treated me as the person.

CURWOOD: How did President Carter handle the ridicule that he was subjected to when he famously put on that beige sweater and told us to turn down our thermostats, and the public response was not exactly favorable?

SPETH: Well, he did a lot of things where the public response wasn't exactly favorable, because he had a powerful internal compass, a powerful internal sense of right and wrong. I think it grew out of perhaps some of his upbringing. So when things didn't go exactly as the politics might have preferred, he stuck by his guns and wasn't perturbed that much. There have been a lot of articles recently about his presidency, and one of the things that they have pointed out, with some regularity is that he was not of Washington. He was from another place, and I don't think he ever tried hard to fit in and to become part of the Washington establishment, and it cost him politically, but he was able to keep his path on that compass point.

CURWOOD: Now concern with the climate by Jimmy Carter is juxtaposed with his concern about energy supplies, and the pretty hard push that he made for coal. He started talking about so called syn fuels, related to, to a certain extent, to the technology the South Africans used to have mobile fuel when they were under embargo. What's your understanding of how Jimmy Carter balanced the need to deal with getting rid of fossil fuel and his call out that we take advantage of all the coal that we have in the United States?

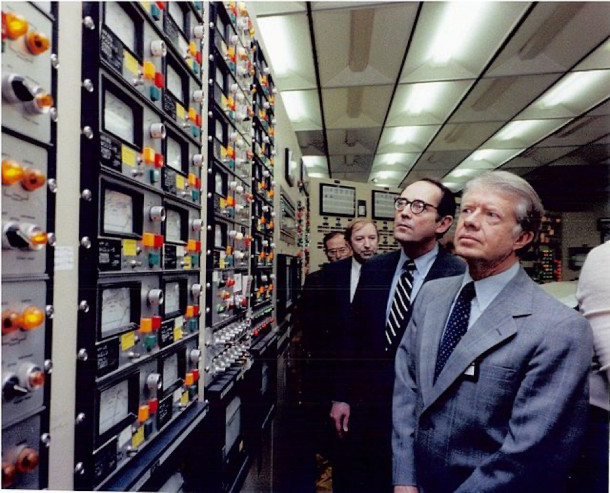

With a background in nuclear engineering from the Navy, President Carter (right) was aware of the risks associated with nuclear energy, and took initiative to slow its growth until the technology was safer. Here he stands at a control room at Three Mile Island with then-governor of Pennsylvania, Dick Thornburgh (center right). (Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

SPETH: Well, the take advantage business all had to do with the soaring oil imports and our dependence on OPEC and his determination to shift us from this foreign dependence and reliance on uncertain international supplies and shift it towards domestic resources and using our domestic resources. And of course, the United States has always had a lot of coal and it has a lot of other fossil fuels. Today, we are the biggest exporter in the world of fossil fuels. So that was a dilemma that he faced from the very beginning. And I think the way that he put it together was that we had to see domestic fossil fuels as the transition to a different energy future. Because as many times as he talked about shifting to domestic resources, he talked about solar energy and renewable energy as being the long term future for the country, and he expressed that in a way that no president ever had since, that this was the future and developed big solar programs, symbolized by, of course, putting those solar collectors on the White House roof. But there was a lot more to it than that. So I think the answer to your question, Steve, is that he, he saw the fossil fuels as a transitional phase getting us to a world in which we were really relying overwhelmingly on renewable energy resources and a dramatic increase in energy efficiency. Carter did a lot. I mean, he ramped up the fuel standards for automobiles and put in place major conservation programs. And it was a big part of his budget that Reagan killed.

CURWOOD: So Jimmy Carter went to the Naval Academy, goes into the Navy, starts working on nuclear subs before he comes back to planes. I guess the family business changed. But what was his understanding of nuclear energy policy? Because back in that Frank Press memo, there's a call for hey, let's have more nuclear because it's carbon free.

Jimmy Carter helped dramatically expand public lands in places like Alaska. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

SPETH: Carter had always had reservations about nuclear power reactors, and despite his training as a nuclear engineer and his experience with the submarine program. And I think what he saw was the problem of waste accumulating at these reactors and no one knowing what to do with them or where to put it. So he had mentioned in the campaign that we should consider halting the development of new nuclear power plants until we had solved the waste problem. So when I was a youngster in the Council on Environmental Quality, I gave a speech in which I called for halting the development of new power reactors until we had solved the waste problem. And it created quite a consternation in the White House, because I'm afraid I hadn't gone through the process of getting approvals.

CURWOOD: Uh oh.

SPETH: And so Carter forgave me. So he had reservations that go back before he was President, but the big thing that happened in his administration was that, people forget that Nixon had launched what is called the Breeder Reactor program, or was called, and the plan was to build hundreds, literally hundreds of breeder reactors, a new type of power plant, by the year 2000. The problem was that these reactors were more prone to accidents than the current reactors, and also the whole point of producing these new reactors was that they would breed plutonium fuel. And plutonium is not only one of the most deadly radioactive substances, but it also is weapons grade material that can be used for nuclear explosions, but in the end, he basically terminated the program to build breeder reactors and have what's called nuclear fuel processing, which would extract the plutonium. So we're all a lot safer today thanks to the Carter's initiative in that regard.

Gus Speth remarks that Jimmy Carter’s administration showed deep appreciation of science and care for the environment. (Photo: The White House, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So we've been talking a lot about energy and climate and, in our discussion about Jimmy Carter, but let's turn to his legacy in nature. Talk to me about the public lands that President Carter was involved imposing protections on, and what that means for us today.

SPETH: Well, what it means for us today is that he doubled the size of the national park system, largely in Alaska, but, but not exclusively. And it was one of the great conservation initiatives of, was the greatest conservation initiative in the country since Teddy Roosevelt. It wasn't just land that he protected. He issued executive orders on protection of wetlands and protection of flood plains. We wrote in his administration, got passed the strip-mining legislation, the hazardous waste cleanup program, the super fund, and, of course, the 100 billion acres in Alaska. And what is sometimes forgotten was that Carter's first big initiative in land and water was to go after and try to kill a bunch of really destructive and expensive and ineffectual major water projects. There were huge dams and ditching that was proposed, and in the end, he, he was able to kill about 20 of these, these efforts, but it was politically quite costly for him, because he lost a lot of support in the Congress, but it was a sign of his determination to save the landscape, to make our streams and rivers free flowing, and to protect the wetland areas that are associated with those streams and rivers, rather than flooding them and ditching them.

Gus Speth (right) remembers President Jimmy Carter (left) as a man of integrity and foresight. (Photo: The White House, courtesy of Gus Speth)

CURWOOD: So how did President Jimmy Carter handle the regulatory agencies while he was in office?

SPETH: Well this is a great unsung accomplishment, because, you know, a lot of the fabric of our country is built up on the sort of routine decisions that regulatory agencies make, and Carter put in place the strongest group of regulators that the country has ever seen. He had a man named Douglas Costle, the head of EPA, Carol Tucker-Foreman, the head of Food Safety and Agriculture. Joan Claybrook, the head of Auto Safety. Eula Bingham, the head of Occupational Safety. I mean, these people were determined to pursue the public interest in a way that was unprecedented then and has rarely been matched since. And they got a tremendous amount of good work done protecting the public and the environment for the future.

CURWOOD: What do you think Jimmy Carter would make of where we are now if he were actively engaged in policy around climate?

SPETH: Well, I think he would say that we're in a hell of a pickle right now because we didn't do what we could have done over the past four decades. I don't think he would say I told you so, but I'll say it: he told us so, and we, you know, we had the possibility of pursuing the lead that he gave us on renewables and efficiencies and other climate actions, and we had four decades. It could have been a smooth transition out of fossil fuels, and now we are faced with an emergency transition out of fossil fuels because we didn't act over those four decades with the kind of wisdom and foresight and determination that we could have and should have.

Gus Speth has since retired from his career as an environmental lawyer and advocate and has written five books of poetry. (Photo: Cameron Speth)

CURWOOD: Gus Speth, in your view, how should the world remember Jimmy Carter?

SPETH: Well, I hope they'll remember Jimmy Carter in the way that that I learned to appreciate him and and remember him. You know, he was a determined person with very high standards, a man of great integrity who believed that government could improve the lot of people in our country and indeed around the world, with his famous international work on human rights. He was principled, he was green, he was informed, he appreciated science, and he said, I'll never lie to you. I'll never tell this country a lie. And I think he stuck by that, and it's such a sharp contrast with what we have today.

CURWOOD: Gus Speth, Chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality for President Jimmy Carter. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today to remember President Carter.

SPETH: Well, it was my pleasure. It's good to see you again, Steve.

Related links:

- Read Frank Press’s memo to President Carter: “Release of Fossil Co\O2 and the Possibility of a Catastrophic Climate Change”

- History of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (formerly Solar Energy Research Institute)

- Read Jimmy Carter’s full 1980 speech at the 10th Anniversary Observance of the National Environmental Policy Act

- About James Gustave (Gus) Speth

[MUSIC: String Quartet based in Perth, Western Australia, “Don't Stop Believin'” by Journey]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Kayla Bradley, Daniela Fahria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt and El Wilson.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and You Tube music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth