U.S. To Abdicate Climate Lead Again

Air Date: Week of January 10, 2025

In 2017, then-President Donald Trump announced his decision to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement. (Photo: Joyce N. Boghosian, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

President-elect Trump’s stated plans to again remove the U.S. from the Paris Accord would be just the latest whiplash in a decades-long trend of U.S. inconsistency on the climate. E3G senior consultant Alden Meyer and Host Jenni Doering talk about what’s ahead for global and domestic climate policy over the next four years.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

The California wildfires and the unprecedented hurricanes on the Gulf coast back in 2024 can be seen as climate wake-up calls. But saving the world’s forests and transforming energy systems are tremendous tasks, and more than 30 years of UN climate talks have yet to contain the continuing slide into climate disruption. The most powerful country in the world is a big part of the problem. As the US prepares to inaugurate a president who appears dismissive about the climate crisis, we’re joined by Alden Meyer to help us understand this moment and how we got here. He is a senior consultant with E3G and a longtime observer of the UN climate meetings. Hey, Alden, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MEYER: Good to be with you again. Happy New Year.

DOERING: Happy New Year. So, as the U.S. enters a second term with President Trump, he's pledged to once again remove us from the Paris Agreement. What's the history of the U.S. involvement in the underlying U.N. climate treaty?

MEYER: Well, it's kind of been a roller coaster ride for the world since this process started back in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro at the Earth Summit. President George H. W. Bush, at the time said the American way of life is not negotiable, and blocked any attempt to make commitments in that treaty for developed countries legally binding. And then, of course, five years later, we negotiated the Kyoto Protocol because the original treaty with its non-binding goals, wasn't achieving the results people wanted. And the U.S. had no strategy to ratify that treaty in the Senate under the Clinton-Gore administration. And of course, when George W. Bush became president in 2001, he famously declared that the Kyoto Protocol was dead. The rest of the world said, George, not so fast. You're not the decider here. We have a say in this, and they rallied to go ahead with Kyoto without the U.S. Fast forward to Trump's first term. Six months into his first term, he decided he would withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, which he did, and he's made very clear that he will withdraw the U.S. from Paris again, not six months into his term, but on day one. So it's kind of a roller coaster ride for the world. They're getting a little tired of it, but they have seen this movie before, and they are now figuring out how to adjust to it.

Then-U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry (center) holds his granddaughter, Isabelle Dobbs-Higginson on his lap while he signs the Agreement in 2016. (Photo: U.S. Department of State, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: Right. And of course, President-elect Trump may be able to say, on day one, I'm taking us out of the Paris Agreement again. When does it actually go into effect?

MEYER: Well, it would take effect one year after the formal withdrawal. But of course, it would mean that the U.S. would presumably make no efforts to meet its existing obligations under Paris, which include the 2030 commitment to cut emissions by 50 to 52% below 2005 levels, and the new commitment that the Biden administration made just last month for 2035 to make further reductions. Presumably the Trump administration would say, even though we're still in the Paris Agreement, we have no intention of taking actions to meet those commitments. It would also mean, presumably, that they would not try to meet the financial pledges that President Biden has made. He succeeded in nearly quadrupling U.S. contributions for developing country mitigation and adaptation investments over his four-year term. I think it's fair to say that we can expect President Trump will try to reverse that and either zero out or dramatically slash U.S. climate finance.

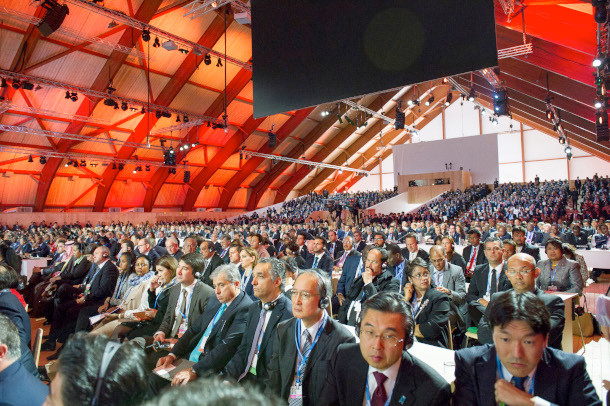

195 parties, currently including the United States, are signatories to the Paris Climate Agreement. Even after the U.S. was withdrawn from the Accord by then-President Donald Trump, no country followed in dropping out. (Photo: United Nations, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Now, as you mentioned just recently, in December, the U.S. filed an updated pledge under the Paris Accord, now calling for a 61% to 66% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2035 compared to those in 2005. What was the point of this update, Alden, knowing that we're heading towards being pulled back out of Paris?

MEYER: Well, I think the point was to show the world what our goal should be under Paris. Frankly, we think it probably should have been a little bit higher than that in terms of our fair share of reductions. But even getting to that 61 to 66% reduction, if it had been a Harris administration, would not have been that easy. It would have taken an all-out effort. But clearly, with President Trump vowing to roll back all the commitments that President Obama and President Biden put in place, domestically, it's almost certain that we will not achieve that goal and probably won't achieve the 50 to 52% goal for 2030 either. But it did set a standard for what the U.S. ought to be doing. It created kind of a North Star for the states, the cities, the governors, mayors, business leaders and others that have vowed to press ahead with emission reduction efforts despite what President-elect Trump may do, and it provides a base, of course, for the administration that comes after President Trump. Because, of course, this is a 2035 target, and six of those 10 years will be under a new president taking office in 2029. Of course, we don't know whether that next president will maintain President Trump's anti-climate ambition stance on policy, or whether they will go back to the climate leadership role that Presidents Obama and Biden tried to play.

Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate at E3G working on US and international climate policy and politics. He is a Principal at Performance Partners, which provides a range of consulting services to clients in government, business, and the non-profit sector. (Photo: Courtesy of Alden Meyer)

DOERING: Alden, what do you think domestic climate policy is going to look like when the U.S. is no longer in the Paris Agreement? And how do you think it's going to compare to President Trump's first term?

MEYER: Well, at the federal level, I think it'll pretty much be a replay of the first term in terms of rolling back regulatory action at the Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Energy, other agencies slashing funding. Of course, scientists in the federal government are concerned about possible assaults on scientific research and reporting and publications. So that could be a replay. The new factor here is the Inflation Reduction Act, which was one of the signature achievements of President Biden. On that front, it's clear that the Trump administration and President-elect Trump won't try to ramp up funding under that in terms of spending for climate justice programs, for just transition programs and other areas. But the centerpiece of that law, of course, was the tax incentives for clean technology, and the fact that the bulk of the investment spurred by those tax incentives have been going into Republican states, I think, will make it very difficult for President-elect Trump to convince even the Republican-controlled Senate and House to roll back those tax incentives. And of course, we're two or three years into that program now, and there's an argument to be made you shouldn't change the rules of the game for companies that have made investments based on those incentives. So I think those will survive. Estimates are that those could amount to a trillion dollars or more over the 10 year period they're good for. So that is already having a tremendous effect on investments in electric vehicle technology, batteries, solar, wind, other clean technologies, hydrogen, even nuclear power is benefiting from that, carbon capture investments, which has the oil industry engaged. So I think it's going to be very hard for them to roll back that. But if you look outside of Washington, the bulk of activity in terms of energy planning, transportation planning, building codes, other activities happens not at the federal government, but at states, cities, regional governments. And I think that will continue and may even ramp up.

DOERING: From what you've seen, how is the rest of the world reacting to this roller coaster of the U.S. being in the Paris Agreement and then being pulled out and being back in, time and again?

MEYER: Well, the last time President Trump pulled the U.S. out of Paris, not a single country followed us out the door. I expect that to be the case again. There was some flurry late last year that Argentina, President Milei of Argentina might be considering also leaving Paris, but he was convinced not to do that. The real question, I think, will be, is there any impact of this on the level of ambition that countries set in their next round of commitments under Paris? Because the one that the US made last month under President Biden was relatively early in the process. Most of the major players have yet to submit their 2035 emission reduction targets. And there are, of course, forces in some of these countries, China, India, Brazil, Europe, others that will argue that if the world's largest economy and second-largest emitter after China is not taking action, why should we? But of course, that's a false argument, because both it's in their own interest to reduce emissions to protect their people from the impact of climate change, and also it means they have a leg up in the race for the clean technology markets of the future. And the smarter leaders and business and investors understand that, that there's going to be huge, multi trillion-dollar markets for clean technology, and if the US steps off the playing field, that means more for the rest of us. So I think you're going to see that play out.

DOERING: Alden, which nations do you anticipate might take the lead on climate as the US steps back?

MEYER: There's a lot of expectations that the European Union and China will need to step up more on this, without the U.S.. The United Kingdom has been a leader under its new government, putting in a very ambitious commitment for 2035 at the end of last year, during the Baku Climate Summit. Other countries will be important, such as India, Indonesia, South Africa, some of the other big developing countries, and we'll see how that plays out. But most of the focus is on the EU and China. Can they reach agreement on ways to move this whole regime forward? Diplomatically, I think it also depends on what President Trump does in other areas after he takes office. Does he impose tariffs on imports? Does he try to abrogate agreements with other countries on clean energy technology research and deployment? There's a whole series of diplomatic agreements outside of the UNFCCC and the annual climate summits. That's also very important here, and we really don't have many signals yet about what his administration will do on that front.

DOERING: Alden Meyer is a Senior Associate of E3G. As always, Alden, thank you so much for taking the time with us.

MEYER: Good to talk with you, Jenni.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth