February 7, 2025

Air Date: February 7, 2025

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Zeldin New EPA Head

/ Marianne LavelleView the page for this story

The new EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin says there needs to be urgency in addressing climate change but also hints that the Trump EPA will not pursue greenhouse gas reductions. Marianne Lavelle is Washington bureau chief at Inside Climate News and joins Hosts Paloma Beltran and Jenni Doering to discuss how the Trump EPA seems to be looking to pull back on climate and other regulations. (07:04)

PFAS Rule Withdrawn

View the page for this story

One of the many Biden Administration rules the Trump EPA has nixed is one that would have limited the amount of toxic PFAS that petrochemical and other plants can release into waterways. Former Living on Earth intern Shannon Kelleher now reports for The New Lede, and she joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain this setback for regulating “forever chemicals” that cause cancer, immune deficiencies and other harms. (07:39)

Trump Dumps Environmental Justice

View the page for this story

Black, Brown and low-income communities pushing back against industrial pollution have always had an uphill battle. But now those environmental justice fights may get even harder, as the Trump administration shutters federal environmental justice programs. Patrice Simms is Vice President of Litigation for Healthy Communities at Earthjustice and joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss the federal government’s role in protecting people from environmental discrimination. (13:24)

BirdNote®: City Owls

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Some owls, like Barred Owls and Great Horned Owls, are happy to call our cities home. There’s plenty of rats and squirrels to eat, and BirdNote’s Michael Stein offers some tips on how to spot these urban owls. (01:55)

Searching for Old Growth Forest

View the page for this story

Finding the last remaining old growth in the vast forests of Maine is like finding a needle in a haystack, but LiDAR technology is helping pinpoint these biodiversity hotspots so they can be protected. Ecologist John Hagan of Our Climate Common joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how it works and why it’s bringing the timber industry and conservationists together. (11:51)

The Little Gods of the Forest

View the page for this story

Poet Major Jackson joins Host Jenni Doering to read his poem, “The Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation” and reflect about forest bathing and immersing ourselves in nature as a vital life-giving experience. (03:03)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: John Hagan, Major Jackson, Shannon Kelleher, Patrice Simms

REPORTERS: Marianne Lavelle, Michael Stein

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

The Trump administration turns its back on environmental justice.

SIMMS: It isn’t a conversation, really, about policy and esoteric legal principles. We’re really talking about pollution that sends children to the hospital with asthma attacks, that causes lost workdays, that causes lost school days. These are real consequences for real people.

DOERING: Also, finding the surviving pockets of old growth forest in Maine.

HAGAN: We didn’t know, before LIDAR, where it was. You had to stumble upon it, the old forest, to find it or know about it. Now we’ve got a map. LIDAR’s – I call it magic. I’m supposed to be a scientist, but to me LIDAR just seems like magic, what it shows you about the forest.

DOERING: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Zeldin New EPA Head

After former US Rep Lee Zeldin’s (R-NY) appointment as Administrator of the EPA over a thousand EPA employees received notice they were eligible for termination. Zeldin is also expected to disband the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice. (Photo: Shealeah Craighead, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

BELTRAN: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

There’s a new sheriff in town at the Environmental Protection Agency now that President Trump’s pick, Lee Zeldin, has been confirmed by the Senate as EPA Administrator.

BELTRAN: To get a bit of perspective on this choice, we reached out to Marianne Lavelle, the Washington bureau chief of our media partner Inside Climate News. Marianne, welcome to Living on Earth!

LAVELLE: Hi Paloma, hi Jenni, thanks for having me.

DOERING: Hi Marianne. So, give us a bit of background for Lee Zeldin. Who was he before he was appointed to this post?

LAVELLE: Lee Zeldin is a former Congressman for New York’s first district on Long Island, and he’s a lawyer and a U.S. Army veteran who served in Iraq. He got his start in politics in the New York State Senate in 2011, and he ran for governor of New York in 2022. And although he lost, he did very well for a Republican in that blue state and a big part of his platform was that he wanted to open New York up to fracking.

BELTRAN: Hm. Sounds that might be one of the reasons that President Trump wanted him to lead the EPA.

LAVELLE: I would think so. After that run, Zeldin traveled with Trump on the campaign trail including in the key state of Pennsylvania - where, of course, fracking is a big deal.

Former New York Republican Congressman Lee Zeldin was sworn in January 29th as President Trump’s new head of the EPA, and has already made a wide array of changes in the agency. (Photo: EPA, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DOERING: Of course. So, it sounds like he’s pretty pro-fossil fuel, but what has Lee Zeldin said about climate change?

LAVELLE: Well, he affirmed during his confirmation hearing that he believes climate change is real. Independent Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont pushed Zeldin, asking him if he would describe the changing climate as “an existential threat.” And Zeldin did say that he felt there needed to be an urgency in addressing these issues.

BELTRAN: Well, he could take climate change on at EPA, so what did he talk about doing in these hearings?

LAVELLE: This is where things get more complicated. Zeldin said he believed the Supreme Court gave EPA the authority to act on climate by limiting greenhouse gas emissions. But he said the court did not give the EPA any obligation, or any mandate to act. Here’s Lee Zeldin at his hearing in response to Democratic Senator Ed Markey of Massachusetts.

ZELDIN: Senator, I just want to be accurate and in citing Massachusetts v. EPA, the decision does not require the EPA, it authorizes the EPA.

[CROSSTALK]

MARKEY: It says you’re obligated; you’re obligated to regulate if you find there’s an endangerment.

ZELDIN: If.

DOERING: Huh. What exactly does he mean by that?

Rep. Zeldin was a strong advocate for fracking during both his 2022 New York gubernatorial campaign as well as Donald Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign. (Photo: Artaxerxes, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

LAVELLE: Well, in that famous 2007 case Zeldin is talking about, the Supreme Court said greenhouse gases fit the definition of pollutants under the Clean Air Act. But it wasn’t until the Obama administration, in 2009, that the EPA made a finding that greenhouse gas pollution was a danger to human health and the environment. That endangerment finding is what gives the EPA an obligation to act on climate.

And now that finding is a target of the Trump administration, picking up on a goal of Project 2025.

BELTRAN: And you know, the endangerment finding has been unsuccessfully challenged several times before. So, what makes Trump officials think they’ll succeed?

LAVELLE: Well, hard to say, because the finding has stood up against legal challenges for 16 years. The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals has twice denied such attempts and even the conservative majority Supreme Court has not been willing to touch it. There are procedures in the Clean Air Act that essentially block unraveling the endangerment finding. And in any event, the evidence on the danger of greenhouse gases to health and the environment is stronger than ever. So, when pressed, Zeldin was trying to wiggle between what the law says and what President Trump is asking him to do.

In his senate hearing, Zeldin stated that the U.S. should address climate change “with urgency,” but also made a point of saying that under Massachusetts v. EPA, the EPA is only “authorized” by the US Supreme Court to regulate greenhouse gas pollution, not “required”. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: Wait, so since this is such a big deal, this wouldn’t just affect EPA, I’m guessing it would impact basically every action in the federal government related to greenhouse gas pollutants.

LAVELLE: That’s right, the Trump White House is attempting to roll back all kinds of federal policies that touch climate pollution, on energy, housing, public lands, you name it.

BELTRAN: So, Marianne, besides climate, what other environmental issues will Lee Zeldin oversee?

LAVELLE: So far, the Trump White House expects Zeldin to disband the EPA Office of Environmental Justice, and power companies have already pushed Zeldin to get rid of toxic coal ash rules. By the way, the deputy administrator President Trump picked to work with Zeldin, David Fotouhi, was the general counsel for the EPA in the first Trump administration. And he’s been waiting in the wings in private practice, trying to fight an asbestos ban.

BELTRAN: Okay, so Fotouhi may get the job with the EPA, but what about the employment situation for others there?

In 2009, the EPA released its finding that greenhouse gas pollution endangers human health. The Trump administration has asked the Zeldin-led EPA to reexamine this finding. (Photo: Gerald Simmons, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

LAVELLE: You know, Paloma, on January 29th, that’s the day Zeldin took the helm, emails started going out to EPA employees who had been in their current roles for less than a year, saying that they could be terminated immediately.

DOERING: Yeah, I saw that was sent to over a thousand so-called “probationary” employees, which included tenured employees who had moved to a new position in the past year.

LAVELLE: It definitely seems that the EPA is in a state of turmoil. There’s also the deferred resignation offer that was sent to all federal employees at the same time. So, this is going to be a difficult time for EPA while trying to navigate those waters and make all these massive policy decisions.

DOERING: Well, we’ll keep an eye on the actions taken by this Trump EPA, and we’ll talk to you again soon, Marianne, to look at a few other cabinet picks.

BELTRAN: Thanks so much, Marianne, we’ll talk soon.

LAVELLE: Thanks Jenni, thanks Paloma.

DOERING: Marianne Lavelle is the Washington bureau chief of Inside Climate News.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News |“Reset or Purge? Trump EPA Dismisses Agency Science Advisers”

- The New York Times | “Inside Trump’s Renewed Effort to Undo a Major Climate Rule”

- The New York Times |“E.P.A. Tells More Than 1,000 They Could Be Fired ‘Immediately’”

- CBS News |“Senate Confirms Lee Zeldin to Lead EPA as Trump Vows to Cut Climate Rules”

- NRDC |"Can Trump Reverse the Climate Endangerment Finding?"

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions “Road to Jordan”]

PFAS Rule Withdrawn

The Trump administration, on its first day in office, reversed a proposed EPA rule aimed at limiting the amount of PFAS chemicals that manufacturers could discharge into waterways. (Photo: Patrick Hendry, Unsplash)

BELTRAN: Well, another Biden rule the Trump EPA has targeted is one that would have limited the amount of toxic PFAS that petrochemical and other plants can release into waterways. The Biden administration didn’t quite get the regulation over the finish line, and the Trump White House immediately withdrew it. Joining us now is Shannon Kelleher of The New Lede, an independent newsroom of the Environmental Working Group. She also happens to be a former Living on Earth intern – so, welcome back, Shannon!

KELLEHER: Thank you. It's great to be here.

BELTRAN: For those who may not be familiar, could you explain what PFAs chemicals are and why they're often called forever chemicals?

KELLEHER: So, PFAs are a class of 1000s of human made chemicals that can be found in tons of products that we use every day, like dental floss, waterproof clothes, shampoo bottles, makeup, and they have a lot of industrial uses as well. PFAs are called forever chemicals because they don't easily break down in the environment. So, once they're out there in the world, these chemicals can stick around for hundreds or 1000s of years. I think communities that are located near these polluting facilities are especially at risk, and these tend to be low income and communities of color. However, I think PFAs is a universal problem that really affects everybody. Unfortunately, we're all being exposed to some degree, and this is a nonpartisan issue, or at least it really should be.

BELTRAN: Why are PFAs chemicals such a critical issue in the broader conversation about environmental health and justice?

KELLEHER: So PFAs, they're ending up in the environment in a number of different ways, from industrial wastewater, they can leach from landfills, they can end up in groundwater from firefighting foam, and they can be found in sewage sludge that is spread on farmland as fertilizer. They've been found on farmland in Maine and other parts of the country... Researchers with the US Geological Survey have actually found that there is at least one type of PFAs in almost half of US tap water. So, these chemicals are really hard for people to avoid, and as a result, most of us have some level of PFAs in our bodies. And PFAs has been linked to a lot of health effects in humans, even at very low doses. Some PFAs have been linked to certain types of cancer, they suppress the immune system, which can lead to reduced vaccine efficacy, they've been linked to reproductive problems and also to high cholesterol.

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are widespread chemicals found in industrial wastewater, landfills, sewage sludge, and many household items, including cosmetics. In cosmetics, they are used for their water- and smudge-resistant properties, contributing to their accumulation in human populations and ecosystems, posing long-term health and environmental risks. (Photo: Rosa Rafael, Unsplash)

BELTRAN: Could you provide some context about this recent executive action by President Trump, you know, concerning PFAs? What exactly happened?

KELLEHER: This was a draft rule that was withdrawn from this White House review process. This proposed rule was designed to set limits on how much PFAs chemical manufacturers can discharge into waterways, and this rule was already considered to be long overdue. It arrived at the White House during the Biden administration, where it was supposed to be reviewed within 90 days, and this was the draft rule's last step before the plan could be released for public comment. But the rule remained in this review stage for a lot longer than 90 days, and it was still there when Trump took office on January 20th. Then on his first day in office, President Trump issued an executive order that freezes any new regulations that had not yet been finalized. And the next day, on Tuesday the 21st the EPA withdrew the proposed rule on PFAs in industrial wastewater. And just to be clear, PFAs rules that were finalized already under the Biden administration are still in place, including the limit EPA set last year on PFAs in drinking water.

BELTRAN: What are the immediate implications of Trump's executive order? You know, what will probably happen now?

KELLEHER: Well, there are still no federal limits on how much PFAs industries can release into the water. So, this is a setback towards putting those limits in place, and I think people are worried that it sends a message that polluters can keep on polluting.

The EPA has known about the health risks of PFAS since 1998. In 2016, it set a Lifetime Health Advisory for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water at 70 parts per trillion, but the advisory was not enforceable. In 2024, the EPA established the first federal enforceable limits for PFAS in drinking water, applying to six chemicals, with PFOA and PFOS limited to four parts per trillion. (Photo: RephiLe, Unsplash)

BELTRAN: Over the years, how have PFAs chemicals been handled or neglected by public policy? Are there some key milestones or oversights that stand out to you?

KELLEHER: Well, the EPA has known that PFAs is linked to health problems since 1998, but it took a long time to act. In 2016, the EPA set a Lifetime Health Advisory for two particularly notorious PFAs chemicals, PFOA and PFOS in drinking water, and that was set at 70 parts per trillion, but this wasn't an enforceable standard. In the meantime, some states set their own limits on PFAs in drinking water, but then last year, 2024, was a big year for PFAs regulations in the US, because that's when the EPA set the first federal enforceable limits for PFAs in drinking water. These limits apply to six PFAs chemicals, and for PFOA and PFOS, they're limited to just four parts per trillion in drinking water. So, that was a big deal. And around that same time, EPA designated those two PFAs chemicals as hazardous substances under the Superfund law, or CERCLA, and that designation is supposed to help make sure polluters pay to investigate spills and clean up contamination, instead of taxpayers having to foot the bill.

BELTRAN: From your reporting, what have experts expressed in terms of what's the solution here?

PFAS exposure has been linked to several health issues, including certain cancers, immune system suppression, reduced vaccine effectiveness, reproductive problems, and increased cholesterol levels, which can elevate cardiovascular risks. (Photo: Nathan Dumlao, Unsplash)

KELLEHER: Yeah, in my reporting, experts that I've spoken with tend to agree on two things in particular that could really help. For one thing, no longer using PFAs for non-essential uses, like in things like makeup or cookware. Industry is really creative, and I think a lot of the time there are just less toxic ways of making the products that we use in our daily lives. Another point that comes up a lot is regulating PFAs as a class. This is a group of 1000s of chemicals, so when we just regulate them a handful at a time, that's not always as effective, because industry can, for example, switch over to other kinds of PFAs that may still be toxic. So, I definitely think it's clear that there's still a lot that needs to be done.

BELTRAN: And how do these recent actions by the Trump administration set us back in terms of PFAs regulation?

Shannon Kelleher is a reporter for The New Lede, an Environmental Working Group independent initiative. (Photo: Courtesy of Shannon Kelleher)

KELLEHER: We don't really know going forward what Trump is going to do on PFAs. I think some people are concerned, because just in his first few days in office, Trump pulled the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement and put these other executive orders in motion opposing renewable energy and supporting oil and gas development. And this is also an administration that says it wants fewer regulations, smaller federal government. In light of all that, I think people I've spoken with are worried about how that mindset could also impact rules that would regulate PFAs. And I think it's also worth noting that Project 2025, which is basically a blueprint that a conservative think tank called the Heritage Foundation, developed for the Trump administration, that document has some concerning language in it about PFAs. It specifically says that the administration should revisit the designation of PFAs chemicals as hazardous substances under the Superfund law. You know, that kind of language is concerning. But to be fair, we don't really know what Trump is going to do yet on PFAs. And Lee Zeldin, who was just confirmed as EPA Administrator, has said he would make PFAs a priority. So, I guess we'll have to wait and see what happens.

BELTRAN: Shannon Kelleher is a reporter at The New Lede, an independent initiative of the Environmental Working Group. Thank you so much for joining us.

KELLEHER: Thanks so much for having me!

Related links:

- Read Shannon Kelleher’s investigative report on recent policy changes regarding PFAS

- Visit the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s website dedicated to PFAS

- Explore the Environmental Working Group’s interactive PFAS contamination map to learn about affected areas

[MUSIC: Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, featuring Matraca Berg and Emmylou Harris, “Oh Cumberland” on Will the Circle Be Unbroken, by Matraca Berg/Gary Harrison, Capitol Records]

DOERING: Just ahead, The Trump administration appears willing to look the other way on environmental discrimination. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: John Scofield, “Just Don’t Want to Be Lonely” on Überjam Deux, Longsolo]

Trump Dumps Environmental Justice

During his first week back in office President Trump signed several executive orders to roll back environmental justice policies. (Photo: Michael Vadon, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Exposure to pollution and the impacts of climate change hurts everyone, but Black, Brown and low-income Americans bear disproportionate burdens linked to discrimination. In the industrial part of Louisiana known as “cancer alley,” the majority Black residents face a cancer risk that is up to 47 times higher than the EPA’s acceptable limit, according to ProPublica. Environmental justice communities have been pushing back against pollution for decades, and sometimes justice does prevail. The environmental lawyers of Earthjustice recently helped Cancer Alley advocates fight the construction of a new Mitsubishi Chemical Group plant. It would have released hundreds of tons of dangerous air pollutants per year, including nitrogen oxides and formaldehyde. After the community opposition caused costly delays, Mitsubishi decided to cancel the project. But each fight for environmental justice takes a massive amount of effort on behalf of locals and advocates standing up to powerful industry. Well, now those fights may get even harder as the early moves of the Trump White House signal that this administration would rather not acknowledge the pollution burdens placed on EJ communities. Joining us now is Patrice Simms, a visiting professor at Harvard Law School and the Vice President of Litigation for Healthy Communities at Earthjustice. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

SIMMS: Thanks very much. It's a pleasure to be here.

DOERING: So, before we get into President Trump's recent actions regarding environmental justice, could you please talk us through the history of White House policy on EJ? What was the situation that President Trump inherited?

SIMMS: You know, the federal government really started paying attention to environmental justice, going all the way back to the early 90s. We saw a couple of things happen during the Clinton administration, starting in about 1992 with the creation of what later became the Office of Environmental Justice at EPA, and the signing of an executive order in 1994 by President Clinton. That was the first executive order directly addressing environmental justice, and we've seen a focus on environmental justice with varying degrees of seriousness and stringency over the years. One of the things that has been true through Democratic and Republican administrations since 1994 is that this Clinton-era environmental justice executive order has survived and has served a bit as an anchor to the federal government's approach to thinking about environmental justice.

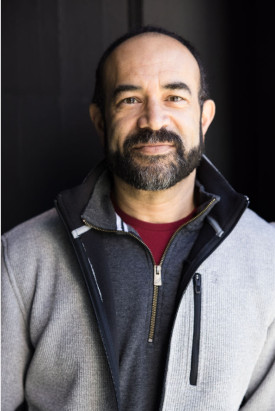

Patrice Simms is Earthjustice’s Vice President of Litigation for Healthy Communities. He also serves as a visiting professor at Harvard Law School. (Photo: Smeeta Mahanti Photography)

DOERING: We just, of course, wrapped up with the Biden administration, which actually put environmental justice kind of at the center of what they were doing around environmental issues. What did that look like in terms of the White House approaching EJ?

SIMMS: Yeah, that's right. One of the things that we saw in the Biden administration, really starting as early as the campaign, was a recognition of the seriousness and importance of grappling with the challenges of creating environmental justice and grappling with environmental injustice. So, President Biden was really aware of the problem of environmental injustice and wanted to be deliberate about advancing environmental justice, speaking with environmental justice communities that were on the front lines of pollution across the country, and really thinking about what does it look like to do this well. And among the things that the Biden administration did was adopt some additional executive orders that gave instruction to the federal agencies to take further steps to make sure that they were paying attention to these problematic examples of discrimination in the context of pollution and exposures.

DOERING: So, President Trump has signed multiple executive orders regarding environmental justice. What are they and what impacts are they having?

Earthjustice is an environmental law nonprofit. Recently, they’ve fought against a new petrochemical plant in cancer alley. (Photo: Provided by Earthjustice)

SIMMS: In the first couple of weeks, President Trump withdrew or revoked all of the executive orders that President Biden had adopted that related to environmental justice in one way or another, but he also reached all the way back to the 1994 Clinton-era executive order and revoked that executive order as well. And as I mentioned, it's an executive order that survived for 30 years through Democratic and Republican administrations, and it survived that long because it really reflected this fundamental principle of fairness and non-discrimination, the idea that our federal government should be operating in ways that do not result in discrimination against groups based on race or income. So pretty significant the revocation of all of those executive orders. It's hard to imagine disagreeing with the premise that we should not be poisoning communities based on their race. You know, the withdrawal of that executive order problematically seems to suggest that this administration disagrees with that fundamental premise.

DOERING: What exactly are the tangible legal implications of what President Trump has done? — Since sometimes when he takes a step, it's a little bit more about the headlines than about the actual impact.

SIMMS: Yeah, well, there's obviously a lot of bluster and a lot of really, frankly, just sowing chaos that's happening right now. Some of it as a distraction, but some of it that will have some concrete and important impacts on real people. One of the signals that's being sent around environmental justice is, don't focus on, don't listen to, don't pay attention to communities on the front lines of pollution. Among the many things that environmental justice programs and strategies tried to do was make sure that voices and input from communities that are often on the very front lines of pollution and toxic exposure were sought out in the context of making important policy decisions or adopting and crafting regulatory programs that have to happen anyway, right, under statutes like the Clean Air Act that already require the regulation of air pollution. And that's among the things that environmental justice programming within federal agencies did. And if that stops, it means those voices, the participation of those communities and the decision-making processes could disappear.

It also could affect how enforcement happens. If you think about where EPA and other agencies that enforce the laws associated with pollution and exposure, how they're thinking about what they're trying to achieve with those enforcement strategies, that enforcement might say, hey, let's focus at least some of our energies on making sure that we're addressing those polluters that are violating the law in ways that are exposing these communities that are already overburdened and already on the front lines of pollution. And if the instruction to agencies is stopped doing that, then that pollution may continue, and those communities may continue to suffer. There's a host of reasons why this really matters, and it isn't a conversation really about policy and esoteric legal principles. We're really talking about pollution that causes cancer, that kills people, that sends children to the hospital with asthma attacks, that causes lost workdays, that causes lost school days. These are real consequences for real people, and often consequences for real people and real communities that are already also subject to all kinds of other burdens and marginalization.

Former President Bill Clinton signed the first executive order related to environmental justice back in the early 1990s. That order stayed in place until it was revoked by President Trump in January 2025. (Photo: LadyLorna860, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

DOERING: We're talking about environmental justice issues that have to deal with communities of color being more affected by pollution than white communities. And I understand that there's actually a statute in the Civil Rights Act that addresses issues of the federal government perpetuating racism. So, what exactly is title six of the Civil Rights Act, and how does it relate to environmental justice issues?

SIMMS: Yeah, well, title six generally instructs the federal government to eliminate discrimination with respect to funds that it distributes, and largely that means the states. Title six was intended to prevent the federal government from outsourcing racial discrimination to the states through funding of racist practices at the state level. And it relates to environmental justice because among the things that states administer are environmental programs. And to the extent that they're administering environmental programs that receive funding from the federal government, which almost all of them do, they have an obligation to do that in ways that are non-discriminatory. That's what it means to comply with Title six of the Civil Rights Act. And EPA and other federal agencies have an obligation to make sure that those grant recipients are operating in ways that are non-discriminatory.

DOERING: So, Patrice, what options do you think environmental justice communities have for pushing back against threats to their health in these times, you know, during this second Trump administration?

Due to President Trump’s executive orders, many EPA employees fear for their jobs. Pictured above is EPA Headquarters in Washington D.C. (Photo: Coolcaesar, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

SIMMS: Yeah, I think there's a couple of things. The withdrawal of executive orders and policies meant to ensure that federal agencies are really thinking about environmental justice, even with those having been withdrawn. The underlying statutes that direct what federal agencies have to be doing, statutes like the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, those statutes have substantive requirements about what has to be done, about what air pollutants have to be regulated, how they have to be regulated, and those statutes continue to provide vehicles for communities to fight for cleaner air, for cleaner water. Those substantive statutes like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act are very powerful, but they don't always ensure non-discrimination in environmental pollution and exposures. But even if the federal government decides to abandon principles of fairness and justice and non-discrimination, the states don't have to. And communities on the front lines of pollution and exposure will continue to engage in advocacy with their states to try to fill some of the gaps that the federal government is leaving, and we see already that some states are expressing an intent and willingness to step into the breach here and directly deal with environmental justice issues. That won't be true everywhere.

DOERING: These executive orders that the President has issued just in his first days seem to touch every aspect of the federal government. But specifically, how is this chaos, as you say, impacting agencies like EPA, and what could the long-term implications be for environmental justice if this continues?

SIMMS: Yeah, well, that's a really good question. And one of the most direct consequences for environmental justice that's an outgrowth of the executive order is sort of what it means for how federal agencies organize themselves, what staff they have, and what those staff are doing, what they're working on. One of the things that we've already begun to see in the wake of these executive orders is staff who have been previously working on environmental justice issues being put on leave with the expectation that many of those staff may ultimately be let go. So, what it means is that there's a direct consequence from these executive orders to the capacity of federal agencies like EPA to do their work, and especially to do the work that's focused on ensuring non-discrimination in environmental policy.

DOERING: You know, it seems like, from what I'm hearing from you, Patrice, it seems like a really stressful time to be in this position of advocating for environmental rights. What keeps you going?

SIMMS: Really significantly for me, what continues to motivate me is my tremendous respect and appreciation for the people on the front lines of pollution and exposures. I work really closely with communities across the country who are in very real ways, fighting for their lives, fighting for their families, fighting for their well-being, and fighting for their communities. And these aren't people who are getting paid to do this. These are people who are doing this because they have to. They're doing this because they're watching their children get sick. They're doing this because they're watching their communities die. And there's nothing more motivating than understanding and knowing the members of these communities, the work that they do, and the passion that they have for making sure that they're protecting their families and their communities. And it's an honor and a privilege to get to work with them and beside them and for them, and that keeps me going every day.

DOERING: Patrice Simms is the Vice President of Litigation for Healthy Communities at Earthjustice and a visiting professor at Harvard Law School. Thank you so much, Patrice.

SIMMS: Thank you. It's really been a pleasure to talk to you today.

Related links:

- American Public Health Association | "Addressing Environmental Justice to Achieve Health Equity" (Nov 2019)

- Learn more about Earthjustice

- Discover where air pollution causes the most cancer in the United States

- Inside Climate News | "‘It’s Worse Every Day’: Environmental Justice Staffers at EPA Face Uncertain Future as Potential Layoffs Loom"

- The New York Times | “Workers at E.P.A.’s Office of Environmental Justice Are Told They May Be Put on Leave”

[MUSIC: Kaia Kater, Joey Landreth, “Saint Elizabeth” on Nine Pin, Kaia Kater]

DOERING: If you enjoy the stories you hear on Living on Earth, sign up for our free, weekly newsletter. You’ll get special access to show highlights and early notification about upcoming live virtual events.

BELTRAN: And we now feature exclusive letters from our staff. This January our Executive Producer Steve Curwood wrote about the early warnings on the climate crisis dating back to the Carter presidency, and he pointed out that despite the delay it’s not too late to act.

DOERING: Intern Daniela Faria shared what she learned from our recent story about the “Dirty Dozen” and “Clean Fifteen” guides to minimizing pesticide exposure without breaking the bank.

BELTRAN: And our producer Sophia Pandelidis tapped into her Greek heritage and gave a preview of our story about Athens reviving an ancient aqueduct to cope with drought. So don’t miss out! Subscribe at the Living on Earth website, loe dot org. That's loe dot org.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: City Owls

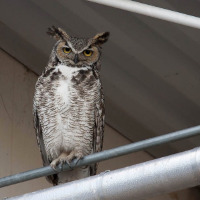

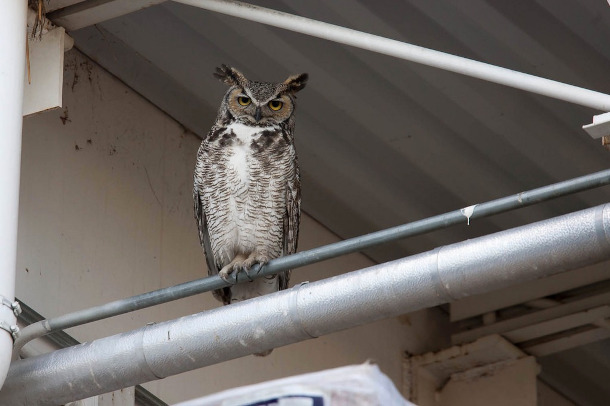

A great horned owl perches on a pipe. (Photo: © Bill Weaver, Courtesy of BirdNote®)

BELTRAN: Owls are famous for their stealth, with feathers that barely make a sound. Even so, BirdNote’s Michael Stein has some tips on how you can spot one.

BirdNote®

City Owls

Written by Bob Sundstrom

[Barred Owl duet, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/175898, 0.36-.41]

You don't need to travel to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry – or even to a remote forest – to see owls. Some owls – including big birds like Barred Owls and Great Horned Owls – live in the city. Owls are hunters, and there’s a lot to eat in the city — like rats or even squirrels!

Great Horned Owls favor urban parks, cemeteries, and botanical gardens, places with big trees. They are huge owls with pointy ear-like tufts, and they roost during the day in trees and hunt at night over open areas nearby. Look for something shaped like an enormous house cat sitting upright on a branch. At night, listen for these mellow hoots:

[Great Horned Owl pair, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/50548, 0.16-.21]

Barred Owls sound rowdy by comparison.

[Barred Owl duet, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/175898, 0.36-.41]

The Barred Owl also likes parks, especially with open spaces below the trees, because it hunts mostly inside the woods. It’s big, too, with a smoothly rounded head, and it sometimes perches down low where it’s easy to spot.

We hope you can find owls near where you live. Take a pair of binoculars, so you can watch them at a distance that’s comfortable for you – and for the owl.

I'm Michael Stein.

Two young great horned owl siblings. (Photo: © Andy Reago and Chrissy McClarren, Courtesy of BirdNote®)

[Barred Owl duet, https://macaulaylibrary.org/audio/175898, 0.36-.41]

BirdNote is supported by American Bird Conservancy, dedicated to conserving wild birds and their habitats throughout the Americas. Learn more at abcbirds dot org.

###

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by Gregory F Budney and David S Herr.

BirdNote’s theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Senior Producer: Mark Bramhill

Producer: Sam Johnson

Content Director: Jonese Franklin

© 2017 Tune In to Nature.org November 2017/2019/2024 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID# owl-09 -2017-11-13 owl-09

BELTRAN: For pictures, glide on over to our website, LOE dot org.

Related link:

Learn more at the BirdNote® website

[MUSIC: Owl City, “Fireflies” on Owl City, Universal Republic Records, a division of UMG Recordings, Inc.]

DOERING: Coming up – how a “CAT scan” of the forest is helping pinpoint the last remaining old growth trees so they can be protected. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sonny Clark Trio, “Softly as In a Morning Sunrise” Sonny Clark Trio (Remastered 2001/Rudy Van Gelder Edition), Capitol Records]

Searching for Old Growth Forest

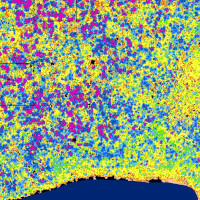

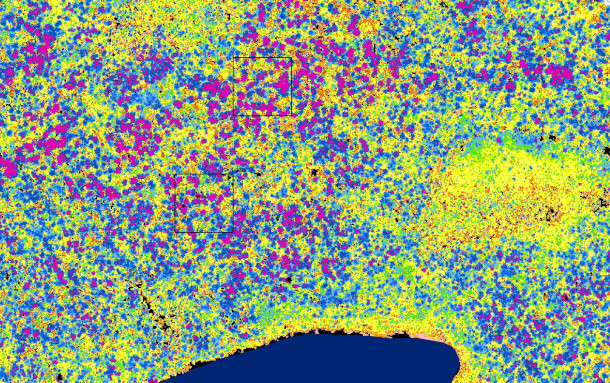

LiDAR is like a “CAT scan” of the forest, our guest Dr. John Hagan says. The blue-magenta signature indicates late-successional/ old growth (LSOG) forest. Above, a LiDAR image of Big Reed Forest Reserve in northern Maine. (Photo: John Hagan)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In the remote northern half of Maine, forests dominate the landscape. While few people live in what’s known as the “unorganized territory,” timber companies control vast swaths of land there and frequently harvest trees for housing, furniture, paper, and more. But technology is revealing hidden gems in this part of the state. The non-profit Our Climate Common has recently begun using light detection and ranging, or LiDAR, to find patches of biodiverse old growth forest. Dr. John Hagan is President of Our Climate Common and holds a PhD in Ecology and he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, John!

HAGAN: Good morning. Nice to talk to you today.

DOERING: So, give us a sense, please, of what the forests in Maine are like for someone who's never been to the state. What kind of natural landscapes would they encounter there?

Dr. John Hagan is President of the non-profit Our Climate Common and holds a PhD in Ecology. (Photo: Courtesy of John Hagan)

HAGAN: Well, it's dominated by Northern hardwoods and boreal spruce fir forest, and it's enormous. It's like 10 million acres of nobody's there, but forest. And it's a really remarkable part of the landscape that in New England we don't really appreciate is there.

DOERING: So, in this vast wilderness, I understand that your organization, Our Climate Common, is using a technology called LiDAR to map these forests. How does this technology work, and what exactly are you trying to illustrate or discover with these maps?

HAGAN: We are using light detection and ranging, the LiDAR, to try to find the old growth forest in the vast 10 million acres. It's like looking for a needle in a haystack. It turns out that LiDAR is kind of like a CAT scan of the forest. If you shoot LiDAR at the forest from an airplane, it gives you a three-dimensional signature of the forest. If you know art history, it's kind of like pointillism. It's just a massive three-dimensional point cloud of the forest. And that turns out, can tell us exactly where the old forest is. About 4% of that 10 million acres is old growth forest. So, in a way, not very much by percentage wise, but a lot, if you let's see, that's about 400,000 acres, that's a lot you didn't know you had, and you don't want to lose.

DOERING: And so how do you identify old growth using these maps? How do you know that what you're looking at is a patch of old growth trees?

About four percent of Maine’s vast northern wilderness is considered late-successional/old-growth forest, which amounts to about 400,000 acres. Dr. John Hagan measures a tall, old white pine in Baxter State Park. (Photo: Ben Shamgochian)

HAGAN: So, we do the fun part, which is we go out on the ground across this 10 million acres, and we go into stands, forests, they're called stands, and we score them based on our ecological knowledge. And then we come back into the lab and say, computer, what did you see? This is what we saw. What did you see? And then we train the computer to find the stuff that we found on the ground. We can't cover 10 million acres on foot. I would love to, but we can't. So, the LiDAR does that for us, and it's incredibly accurate, more than 90% accurate. We didn't know before LiDAR and how we used it to map it, we didn't know where it was. You had to stumble upon it, the old forest, to find it or to know about it. Now we've got a map. And the older stands are blue magenta. Everything this younger is yellows or oranges or light greens. You can color it any way you want, but it's kind of like a neon sign. It's like light up this old growth forest on the map, and LiDAR is, I call it magic. I'm supposed to be a scientist, but to me, LiDAR just seems like magic, what it shows you about the forest.

DOERING: So why is this important to know where these late-stage old growth forests, or I think they're called LSOG, are? Why are they so crucial to protect?

Aerial photo of old-growth forest discovered by the Our Climate Common team using LiDAR. Before employing LiDAR, “We didn’t know where [the old-growth forest] was,” our guest Dr. John Hagan says. (Photo: John Hagan)

HAGAN: It's not surprising that a lot of plant and animal species evolved in an older forest landscape. They evolved to depend on big dead wood. So, when you don't have big trees and big dead wood, you start to lose some of the species that evolve to depend on that. And so, if we don't keep some old forest, we will lose that element of biodiversity. And old forest like LSOG has enormous stocks of carbon today, even if they're not storing any more like as much wood is dying as is growing, and often in an old growth stand, but the stores are like five to 10 times what an average forest would hold in current stocks.

DOERING: Wow.

HAGAN: So, you if you lose it, you lose a lot of carbon per acre with the loss of LSOG stands.

DOERING: That's an incredible amount of carbon storage, five to 10 times?

HAGAN: Right. But the younger stands, you know, a 40 or 30, 40, year old stand is growing fast, so often it will be sequestering carbon much faster than an old stand, but it's got a long, long ways to go to get to the stocks of an old forest.

DOERING: So, from what I understand, the New England Forestry Foundation recently received $4.3 million from the US Forest Service and your maps of Maine's old growth forests are playing a big role in how they plan to use that grant. So how are they making use of the data that you've collected?

Late-successional/old growth trees can hold 5-10 times the amount of carbon as younger trees. PhD student Molly Taylor gets ready to survey a late-successional hemlock stand. (Photo: John Hagan)

HAGAN: Well, most of the remaining LSOG forest is on commercial timberland, private commercial timberlands, people who are in the business of making wood and paper and stuff like that. So, the challenge is, how do you compensate landowners to keep them because they're just losing out financially to let them grow. And it looks like to us, the value of the carbon in these old stands is worth as much and maybe a little more than the timber value. Then it just becomes an economic transaction. Look, I own this land. I would normally cut timber, but if the carbon is worth more, I'll sell you the carbon and keep the stand. So, if the New England Forestry Foundation has all this money to pay landowners, we could say, go here. This is a big stand. It's going to be harvested in the near term. Go there first. So, we've got a road map, literally a map, to say, this is what we should do first.

DOERING: Hm. Gives you a place to start. These are the highest priority stands. So, let's protect that.

HAGAN: That's right. And it could be on public land and already protected. We don't need to worry about that, but if it's on commercial timberland, most likely it's destined to be harvested in the next five to 10 years. So that's why matching the financial opportunity with landowners could prevent loss of these older stands like, right now.

While some old-growth forests in northern Maine are protected, many are on commercial timberland and risk being cut in the near future. Aerial photo of Big Reed Forest Reserve, a 5,000-acre old-growth forest in northern Maine. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: So of course, you know, demand for wood, for furniture, houses and other goods, isn't stopping anytime soon in New England. So, what about these younger forests that would still inevitably be cut down by these large timber companies? Wouldn't they also eventually become old growth, if left alone?

HAGAN: If left alone, they would, but they're not going to be left alone, because that's not the goal of the landowners. But you make an important point that is a fault, or a flaw of some forest offset projects like, well, you protected that stand and that stand and that stand, but they're just going to cut another stand because we need a fixed amount of wood. It's called leakage in the carbon offset marketplace, and it's a problem. Things just move around like pieces on a chessboard, because wood is a globalized product. The atmosphere is a global entity. In our case, and what New England Forestry foundation plans to do, is have landowners and take the proceeds from paying for the old stands and invest in silviculture, forestry practices, on the other acres that would accelerate the growth of those stands so that we don't leak, and we don't just push the carbon off to some other place and it ends up in the atmosphere anyway, and that's why, in the end, we need to be growing more carbon per acre, and that's the way forests can help with getting carbon out of the atmosphere. But it's complex, and if you don't cross all the t's, you end up not making a difference.

With help from a $4.3 million grant from the US Forestry Service, the New England Forestry Foundation hopes to compensate timber companies for keeping old growth stands. Ben Shamgochian (front), forest ecologist with Our Climate Common, and Molly Taylor (back) measure a large, downed log in Big Reed, an old-growth forest in remote northern Maine. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: Why is it important to work across different groups? You know, working with the timber industry, working with conservationists, bringing these different stakeholders together, as opposed to just trying to dig your heels in and say, we're not going to work with you.

HAGAN: My whole career, I've been working collaboratively with people like fishermen and foresters, and I find that they know stuff I do not know. And if I don't know what they know, I can't solve the problem that I'm trying to solve. You know, I got this idea, and they say, well, that's just not going to work, John, the machine can't get there. And so, I didn't know that. So, the traditional ways to do battle, you never really take the opportunity to respect the other person, understand what they know and value what they know. When you do, it just changes the whole problem-solving landscape, and it works. And I think in Maine, especially with this grant, we've got an opportunity to all sit down together and say, what should this look like in the year 2100 and say, okay, we can make it look like that. If we're smart about it and we collaborate, we can do it differently this time, and this grant will help move us that way.

Molly Taylor (left) and Ben Shamgochian (right) examine an old snag in a late-successional forest. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: Do you have a favorite spot in the forest in one of these old growth stands in Maine, and what's it like there?

HAGAN: Well, that's a good question, too. In one of our plots that our stands that lit up in LiDAR, we went in and did our measurements, we core one tree. It doesn't hurt the tree, for anybody who might be worried about that, but it pulls out a core of the tree, and then you count the rings to see how old the tree is. We pulled out a core of this tree, and it was 253 years old, and it was like typical of these old stands we're finding. And then I started thinking about Henry David Thoreau, who walked through Maine in like 1850 something, he could have walked by this tree, literally. I mean, this is kind of silly, but he could have walked by this tree because it would have been 70 years old when he went through Maine. It was a seedling when the first shot was fired at Lexington for the Revolutionary War. So, when you know you're standing beside a tree that old, that's been around that long, it is intangible. It's special. It's just like, wow. It puts you in perspective.

Ben Shamgochian with a 150’ tall white pine in Baxter State Park. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: John Hagan is President of the nonprofit Our Climate Common and holds a PhD in Ecology. Thank you so much, John.

HAGAN: You're welcome. Thank you.

DOERING: By the way, the New England Forestry Foundation does have a signed contract with the US Forest Service regarding that $4.3 million grant. But along with many other federal grants, it has come under threat of freeze by President Trump’s Executive Orders. While the courts have temporarily blocked the freeze, Senior Forester at NEFF Brian Milakovsky says his organization is still waiting on legal clarity about how the executive orders could affect the grant.

Related links:

- Read more about Our Climate Common

- Read more about the New England Forestry Foundation

- New England Forestry Foundation | "$4.3 Million Federal Grant to Help Maine's Oldest Forests Store More Carbon"

- Maine Public |"Digital tool reveals Northern Maine's rare old forest"

[MUSIC: Noah Kahan, “Maine” on Cape Elizabeth, Republic Records, a division of UMG Recordings, Inc.]

The Little Gods of the Forest

Major Jackson’s poem the Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation is inspired by the moss he sees during his long walks across the Vermont forest. (Photo: Joshua Mayer, Flickr CC BY SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: We’ll bask in the woods a little while longer with this favorite poem from Major Jackson, who hosts “The Slowdown” podcast. Here he reads his poem, “the Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation.”

The Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation

I am bathing again, burying my face

into the great nations of moss.

I am leaning in, smelling the emerald mountains

and the little inhabitants crossing

over rock-like boulders and tree trunks empired

bit by bit. My nose must come to them

like a probing spaceship causing a mighty eclipse.

They speak in whispers but do not shriek

when gazing into the dim landing bays

of my cavernous thoughts. I am grazing

like a Dionysian. I come not with religion.

I come yearning for first spring and a thirst for spores

pooling like mercenaries in the dark.

The little gods of the forest live here.

I want to ingest their verdant settlements

until they carpet my cavities and convert my raptorial

self into its own ecosystem, off into the green.

Major Jackson is an American poet and professor at Vanderbilt University. (Photo: Patrice O’Brien)

DOERING: Hm. Towards the end it seems like you are contemplating dissolving into this green world, into this ecosystem. Can you talk about that?

JACKSON: Yeah. Well, we've all heard the term forest bathing now and Shinrin-yoku and the idea of healing through nature. And some part of me experiences that every time I go out as a transformation of sorts. And so, in that particular instance, I am alluding to that feeling that I get. But I also, as a Dionysian, you know, someone who wants to not only experience that healing but also someone who believes that this is how we remain alive. We are part of the biodiversity that makes up our ecosystem, so that interrelatedness, that sense of life-giving life is kind of what I'm exploring there. Which may mean interestingly enough, now that you pose that question there, which may mean a dissolving into the world around us, which we know we're eventually going to do. So, there's this wonderful kind of tension there.

DOERING: Major Jackson is a poet and Professor at Vanderbilt University and the host of the Slowdown Podcast. Thank you so much for joining us Major.

JACKSON: Thank you, Jenni, it’s been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Learn more about Major Jackson

- Major Jackson’s profile from the Poetry Foundation

- The New York Times | “The Body's Uncontested Need to Devour, An Explanation”

- Orion Magazine (No paywall) | “The Body’s Uncontested Need to Devour, an Explanation”

- Pre-order Major Jackson’s forthcoming book of poems “Razzle Dazzle”

- Follow Major Jackson on Instagram

- Listen to “The Slowdown” podcast, hosted by Major Jackson

[MUSIC: Blue Dot Sessions, “Upholding”]

BELTRAN: Next time on Living on Earth, The stunning volcanic landscape of the Sattitla National Monument in northern California.

JOSLIN: From a distance, it looks like a really gentle slope. And when you get up onto the actual volcano, the striking features are very recent lava flows. So, you'll be driving along the road through dense forest and then pop out into just a stark black landscape with almost nothing growing on it. And that repeats over and over the whole time as you drive up to the caldera. And the top of the caldera is a large lake called Medicine Lake, and off in the distance, you can see a large obsidian flow, that's like black glass. It just kind of shimmers in the sun. It's really kind of almost like a Martian landscape in places. And then it's also really dense forest with sort of old growth characteristic.

BELTRAN: The new Sattitla national monument in our next installation of “Exploring the Parks,” next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Martin Klem, “Coyote Wedding” on Coyote Sundance, Epidemic Sound]

includes Naomi Arenberg, Kayla Bradley, Daniela Faria, Mehek Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Ashanti McLean, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, Melba Torres, and El Wilson.

BELTRAN: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and You Tube music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram @livingonearthradio. And we always welcome your feedback at comments at loe.org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth