October 25, 2024

Air Date: October 25, 2024

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Climate Disrupts Florida Politics

/ Amy GreenView the page for this story

In this election year, hurricanes are part of the political conversation about climate change in Florida, where communities are still cleaning up from Helene and Milton. Inside Climate News reporter Amy Green joins Host Paloma Beltran to discuss how Florida’s candidates for U.S. Senator and Republican Governor Ron DeSantis are addressing climate change in the wake of these massive storms. (10:38)

No Early Intervention of EPA Rule

View the page for this story

The U.S. Supreme Court denied an emergency motion from industry to block an EPA rule that compels a 90% reduction in carbon emissions by 2032 for some coal and gas power plants. It will now be up to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit to decide first about the rule and its requirement for carbon capture and storage. (01:23)

'Ecocide' of Ukrainian River

/ Artem MazhulinView the page for this story

An explosion that spilled chemical waste into a river near the Russia-Ukraine border this August led to an ecological disaster with mass fish die-offs. Kyiv blames the Kremlin for a deliberate act of ‘ecocide’ amid the war that started with Russia’s 2022 invasion. Ukrainian journalist Artem Mazhulin reports for the Guardian and joins Host Jenni Doering to describe the impacts of the spill and the toll the war is taking on his country. (11:17)

Huge Untapped Earth Energy

View the page for this story

The heat within Earth’s crust could become a major source of always-on, carbon-free, renewable geothermal electricity thanks to the emergence of fracking technology that can drill now as much as six miles below the surface and reach hot zones. Jamie Beard is the founder of Project InnerSpace and joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain why a partnership between the oil and gas and geothermal industries could bring transformational change to the energy sector worldwide. (09:52)

BirdNote®: Rivers of Birds

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Along the four major North American flyways, huge “rivers” of Arctic Terns and other migrating birds are now making their way south again. BirdNote®’s Mary McCann describes their incredible journey. (01:53)

The Greening of Antarctica

View the page for this story

In addition to the retreat and collapse of huge ice shelves, climate change is associated with rapid greening in Antarctica as plants thrive in warmer temperatures. A recent study found that plants have increased more than tenfold on the Antarctic Peninsula in the last few decades. Co-lead author Dr. Olly Bartlett joins Host Jenni Doering to describe the potential ecological consequences of a more verdant Antarctica. (10:49)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

241025 Transcript

HOSTS: Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Olly Bartlett, Jamie Beard, Amy Green, Artem Mazhulin

REPORTERS: Mary McCann

[THEME]

DOERING: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

DOERING: I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

Florida politicians grapple with climate disruption.

GREEN: The latest hurricanes for sure have elevated the issue of climate change in Florida politics and in everyday discourse. But I don't see it changing the minds of the Republican leadership in the state in a drastic way.

DOERING: Also, Ukraine claims “ecocide” by Russia.

MAZHULIN: When we think of a war it’s mostly explosions, destruction, capturing a village or town, but they don’t usually talk about ecology, they don’t talk about nature, they don’t talk about how animals are hurt, as well, how fish, everything.

DOERING: That’s this week on Living on Earth—stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Climate Disrupts Florida Politics

Hurricanes Helene and Milton hit Florida back-to-back. The above shows damage in Keaton Beach.(Photo: Staff Sgt. Jacob Hancock, U.S. Air National Guard Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

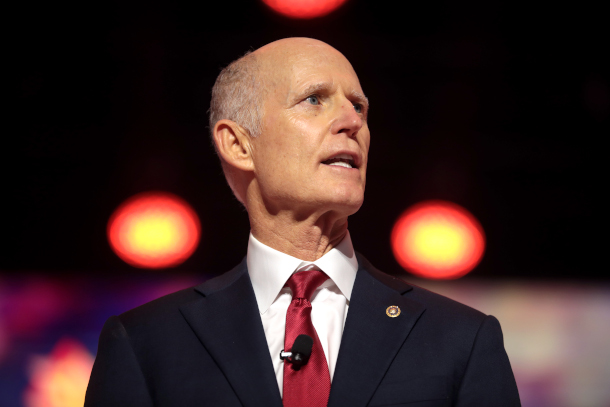

As the U.S. elections on November 5th draw near, candidates in key Senate races are trying to make last minute appeals to voters, including in Florida. Republican incumbent Senator Rick Scott is facing a challenge from Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell. Floridians are still cleaning up from hurricanes Helene and Milton. And in this election year, hurricanes are part of the conversation in politics about climate change in the Republican-led state. Amy Green is a reporter for our media partner, Inside Climate News and joins us now from Orlando. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Amy!

GREEN: It's nice to talk with you.

BELTRAN: So talk to me about Floridians' relationship to climate change. I mean, we have a state that's been absolutely pummeled by severe storms, and they're only getting worse. How do Floridians view climate change?

GREEN: You know, I think Floridians have a unique awareness of the environment, because so much of our lives here revolve around the environment. People are very into water activities and boating and swimming and fishing and hiking, and obviously, Florida is very uniquely vulnerable to climate change. And so it's probably no surprise that surveys show that Floridians, more than other Americans, believe that climate change is real, and they support government programs and actions to address it. A recent survey just came out last week from Florida Atlantic University, showing that 52% of respondents agreed that a candidate with a record of reducing climate impacts was more likely to get their vote. And 68% agreed that the state should do more to address climate impacts, and 67% agreed that the federal government should do more.

Incumbent Republican Senator Rick Scott. While Rick Scott has in the wake of recent hurricanes acknowledged climate change, he still casts doubt on its man-made causes. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BELTRAN: You know, Amy, hurricanes Helene and Milton hit Florida back to back and caused catastrophic damage to the state. What's the general mood on the ground? And to what extent are you hearing a shift in public and political discourse about climate change after these storms?

GREEN: You know, people are exhausted. I think a lot of people are stunned, even people who were not heavily impacted, like myself. I think that the latest hurricanes, for sure, have elevated the issue of climate change in Florida politics at this juncture, leading up to the November elections, and in everyday discourse among Floridians who are trying to understand why these hurricanes are becoming so much more intense than they used to be, why they feel more frequent, and as we know, the reasons for that are climate related. Warmer water temperatures can lead to a phenomenon that's becoming more common because of climate change, which is this rapid intensification of hurricanes, where they can grow almost overnight from tropical depression or tropical storm to a large category 3, 4, 5 hurricane. Sea level rise is causing storm surges to be more damaging. And so that is a conversation that is taking place in the state, for sure. I don't see it changing the minds of the Republican leadership in the state in a drastic way. And for example, after Hurricane Milton, Governor Ron DeSantis, himself a Republican, was asked to comment on some of this misinformation that has circulated after Hurricane Helene, especially in North Carolina, like government intentionally started these hurricanes and directed them into red states, other misinformation circulating on social media has been that FEMA aims to take away people's homes and demolish these homes. We know that this is not true, but Governor Ron DeSantis was asked to comment on this information, and he seemed to, in his answer, downplay climate change somewhat. He said, quote, you see it on both sides, in response to the disinformation. He said, quote, some people think government can do this, and others think it's all because of fossil fuels. He said, what the reality is is what we can see, which is the fact that it's hurricane season, and so it's not surprising that we would have hurricanes during hurricane season. And he talked about hurricanes going back through history, dating back to the 1800s and seemed to be saying that we've always had hurricanes, and the role of climate change in that phenomenon was minimal.

Democratic challenger Debbie Mucarsel-Powell is a former Congresswoman. She has emphasized the importance of government buyouts for communities existentially threatened by climate change. (Photo: United States Congress, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BELTRAN: And from what I understand, Florida Senate race is tightening. What are the two candidates records on climate change? And in your view, how much is the aftermath of these storms affecting the way each of them approach this issue?

GREEN: Right, yes. So that race is tightening. The incumbent, Rick Scott, is a Republican. He is facing a formidable challenge from Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell, who is a former Congresswoman. Rick Scott was elected governor of Florida as a Tea Party candidate in 2010 and as governor, he focused his administration pretty narrowly on jobs, and when it comes to the environment, he really gutted environmental programs like Florida Forever, which is the State's land conservation program, and probably most notably, he reportedly banned the words "climate change" from government agencies, and instituted a policy where that language was not supposed to be used in official documents and official settings and things like that. And that kind of made him a punchline of late-night comedians in a state that is, you know, so obviously vulnerable to climate change. And as a senator, he voted against the inflation Reduction Act, which of course, was the Biden administration's massive investment in climate change programs, programs aimed at moving the country toward cleaner energy sources. But in recent years, his language has appeared to change somewhat on the issue of climate change. His campaign sent me an Op Ed that he wrote back in 2019 where he talked about climate change as an issue that was real and important for the state of Florida. At the same time, the Op Ed criticized the Green New Deal, which involved programs aimed at addressing climate change. And since Hurricane Helene, he did an interview with CNN where, again, he talked about climate change as something that was real and something that deserved to be addressed by state policies that would be aimed at rebuilding infrastructure in a more resilient way.

Republican Governor Ron DeSantis has implemented programs like Resilient Florida to help Florida better prepare for disasters. However, he has also downplayed the human role in causing climate change. (Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

SCOTT: You know, who knows what the reason is, but something is changing, massive storms, massive storm surge. So we've got to figure this out. But here's, here's the positive. We're going to do it. We're going to build more resiliently. We're going to come back. I live in a most wonderful state with wonderful people that are very resilient.

BELTRAN: And what about his opponent, Democrat, Debbie Mucarsel-Powell?

GREEN: When I interviewed Mucarsel-Powell a couple weeks ago, she talked to me about how one of her greatest concerns when it comes to climate change are communities that are existentially vulnerable to impacts like sea level rise, communities where it will be very difficult to rebuild and continue to exist in the future.

MUCARSEL-POWELL: You know, the expectation of the sea level rise was so high that it was having conversations with homeowners that you may not be able to rebuild, but you may have to really seriously consider moving out of this area. And these are families that have been living in the same house for decades, so I think that's the one of the most alarming, alarming situations that we're facing.

GREEN: And she talked to me about the government role in issues like that, being one where the government can offer buyouts to help Floridians move to less risky areas.

BELTRAN: Now, Amy, how do you think hurricanes will continue to impact politics in Florida moving forward?

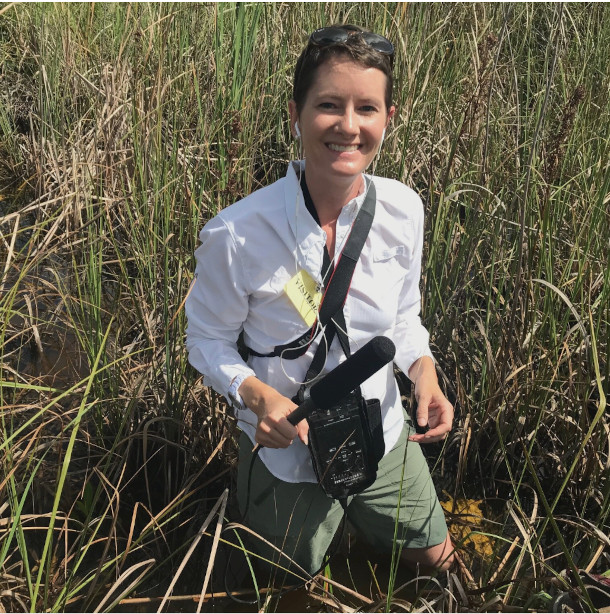

Amy Green is a reporter for Inside Climate News based in Orlando, Florida. (Photo: Tony Pernas)

GREEN: I think there will be this continued tension over the government's role in addressing fossil fuels, which are responsible for hastening the warming of the global climate. Governor Ron DeSantis has done more on climate change than his predecessor, Rick Scott, for sure, Ron DeSantis has initiated a large program called Resilient Florida, and this is a program that is designed to fortify the state's infrastructure against flooding, sea level rise, more damaging storms, and it has been a successful program in that it has provided incentives for communities to begin conversations about, you know, what infrastructure is important to save, and that has been a good thing. But DeSantis has not done anything to move the state toward cleaner energy. One of the things Democrats raised concerns about in the days after Hurricane Milton was Governor Ron DeSantis's turning down federal funding to address things like greenhouse gas emissions, car emissions, basically passing on federal funding that would help the state make improvements in those areas. And I think that will continue to be a source of contention in Florida between Democrats and Republicans.

BELTRAN: Amy Green is a reporter with Inside Climate News. Thanks so much for joining us.

GREEN: It's always a pleasure to chat with you.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “In Florida Senate Race, Two Vastly Different Views on Climate Change”

- Inside Climate News | “Florida Avoided the Worst of Milton’s Wrath, But Millions Are Suffering After Second Hurricane in Two Weeks”

- Inside Climate News | “‘Catastrophic’ Hurricane Helene Makes Landfall in Florida, Menaces the Southeast”

- Read more about Amy Green

[MUSIC: Frank Sinatra, “Stormy Weather” on The Essential Frank Sinatra, Sony Music Entertainment]

No Early Intervention of EPA Rule

The EPA’s new regulation would require coal power plants to reduce their emissions by 90% by 2032 if they want to remain operational in 2038. (Photo: Tony Webster, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

DOERING: After the break, the promise of clean, renewable energy from deep underground. But first, a note on environmental news from the highest court in the land. On October 16th, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed an EPA emissions rule to remain in place, for now. The regulation compels existing coal-fired power plants and new gas-fired plants to use carbon capture and storage to reduce their carbon emissions by 90% by 2032 if they want to remain operational after 2038. EPA says that over the next two decades, this rule would save as much carbon pollution as taking 328 million gas-powered cars off the road every year. Fossil fuel companies have thrown their weight behind carbon capture and storage, but now that EPA wants to require it; the industry appears to be backpedaling.

The U.S. Supreme Court did not grant the plaintiffs in the case against the EPA’s latest emission regulation an emergency block on the regulation. The matter will be considered by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit before any possible review by the Supreme Court. (Photo: Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, supremecourt.gov, public domain)

A group of states, energy companies and industry organizations filed a set of emergency motions arguing that the rule would cause irreparable harm to the power industry and reduce grid reliability. In a brief statement, Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch expressed sympathy for the plaintiffs’ case, but said that due to the regulation's long timeline, there was no urgent need to block it. So now it’ll be up to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit to decide the fate of the rule and its carbon capture requirement, starting with a December 6th court date. Just in time for the outgoing Biden administration to present its arguments before a new President takes office.

Related link:

Read more about the Supreme Court’s ruling.

[MUSIC: Edgar Meyer, “Gee Baby Ain’t I Good To You” on Beautiful Isle of Somewhere, by Donald Matthew Redman, Andy Razaf]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nashville Mandolin Ensemble, “My Last Days On Earth” on Plectrasonics, by William Smith Monroe (Bill Monroe), CMH Records]

'Ecocide' of Ukrainian River

A scene from Russia's war on Ukraine, which began in February 2022. The image shows the aftermath of destruction: buildings are in ruins, with debris scattered in the streets. (Photo: UNDP Ukraine, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has brought a devastating human toll on both sides. Roughly a million Ukrainians and Russians have been killed or wounded since Russia launched its invasion in February 2022, according to recent reporting from the Wall Street Journal. Nature has also suffered amid the conflict, and Kyiv blames Russia for deliberately spilling chemical waste into a tributary to the Desna river in the north of Ukraine this August. Artem Mazhulin is a Ukrainian journalist who reported on this for the Guardian, and he joins me now from Kyiv. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MAZHULIN: Thank you.

DOERING: Now, where is the Desna River, and how important is it to the region?

MAZHULIN: Well, Desna River is located in the northeastern Ukraine, mostly in the north, and it's extremely important because that's where Kyiv takes water from. Which is Kyiv is the capital of Ukraine, the city of, I think three to 5 million depend on how you count. And apart from that, it's very important for the nature, for the ecosystem of the region. Desna river is very beautiful itself, with all the landscapes, the trees that grow, and it's very curvy. There's a famous, well famous in Ukraine novel... It's called the enchanted Desna, written by Alexander Dovchenko. He's a famous Ukrainian film director from 20th century, where he describes this river and the village where he grew up, near Desna, and telling how beautiful it was and it is still. And there's also quite big, wide river.

DOERING: So it sounds like the Desna River holds all kinds of different significance to Ukraine. I mean, ecological, historical, literary. Now, what's the state of the river in the wake of this alleged poisoning?

MAZHULIN: Well, the poisoning started, not in Desna River, right? So it started... There's another smaller river, It's called Seym river that flows into Ukraine from Russia. So there was an explosion... The town, Russian town called Tyotkino, on the very border of Ukraine with Sumer region. And as the result of this explosions, there were some chemicals from sugar plant that got into water, which caused the level of oxygen in the water went straight to zero. And since nothing can exist without oxygen, even in the water, so everything died in Seym river, and Seym river flows into Desna River, and it brought all these chemicals in, and it also killed, maybe not everything, but a lot of fish and other creatures that lived in the river. And yeah, so it was pretty bad. We saw just dead fish, and these clam shells on the river banks near Chernihiv, and smaller villages down the stream and the stench, it just smells, smells really bad, honestly, everything. And I've been to exhumations, you know, so I know what bad smell is. And that was pretty bad, one of the worst I've experienced.

DOERING: Wow. So you're talking about the stench from the river being comparable to the smell of bodies being exhumed?

Artem Mazhulin is a freelance Ukrainian journalist based in Kyiv. (Photo: Courtesy of Artem Mazhulin)

MAZHULIN: It's very different, but it's just the smell of sort of a death, just different kind of death, because human body smells like in a very specific way. But the fish smelled pretty bad, and then it's hard to describe what it was like. It was like because I grew up near the river. Another river that is also a front line now is called the Oskill River. So river always smells fresh. It's uh, trees, this forest, this water moving all the time, so it never smells bad, right? But when we were there by Desna, It just smelled it just smelled bad, and it had like some chemical smell in it, in the air by it. So I wouldn't normally, when I see river, I first thing I want to do just jump in and swim. And I did not have that desire back then, when we were standing it's just didn't feel like it, didn't feel safe.

DOERING: Now, you reported that Ukraine says this is an intentional act of ecocide used by Russia as a weapon of war. To what extent are there other plausible explanations for what's happened here, such as an accidental chemical release?

MAZHULIN: This town is just very close to the border, and between Russia and Ukraine, at the moment, is a very dangerous zone to be. So, there's a lot of explosion happening on both sides, shellings with artillery rounds. So it, you know, no one knows exactly what happened. Just the fact is the fact that those chemicals, those waste, got into water and they caused an ecocide, I think as investigation, we cannot investigate that, because that happened on Russian territory. So it's up to them, and I don't think we'll ever know what actually happened and who caused that, but I can tell you based on my experiences just reporting the war, if that was us, if that was Ukrainian army hit that thing by accident... The Russia would already be everywhere saying that that Ukraine hid this on purpose to blame Russia. So I think it was them. It's my opinion.

The Desna River partially frozen, with sheets of ice covering the water’s surface, surrounded by a serene winter landscape. (Photo: Marat Assanov, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: How is Russia responding to these claims of ecocide?

MAZHULIN: I honestly didn't see any, any response at all.

DOERING: So just silence from the Kremlin...

MAZHULIN: Yeah, yeah. They don't care. I mean, they're busy with taking another village in Donbas. They don't care about ecology. They don't care about their own ecology. You know, the state of ecology in Russia has all this waste been thrown out? So why would they care about ecology in Ukraine?

DOERING: Now, what is Ukraine doing to try to mitigate the ecological damage here and protect the Desna rivers ecosystem?

MAZHULIN: So there's a special devices... They had nine or ten of those that they put in the water just to pump the air into... It's like a kind of as far as I understood, it's like a thing you put in your fish tank to keep the water clean and the oxygen level up for your fish, for your pet fish. So this just in much, much bigger scale, like a huge thing, just put in the in the water, and it was like pumping the air in in the river. And then, of course, they would pick up all the dead fish away, because it's summer. It starts to rot. It starts to smell pollution, bugs, bacteria, and so on and so forth. So it had to be taken away. And I know they took this dead fish to the old farming cattle where they, you know, when the farms, they bury their cattle when it dies or something. So they have the special burrying grounds. So they would bring that fish there. And the thing is that if the government could get involved and bring the State Emergency Service to like, bigger cities, so the smaller communities, like the villages, they had to do it on their own. So they had to bring this volunteers or ask people just to come together and pick up the dead fish.

DOERING: Artem, what's the mood like now that this war is dragging on and allegedly leading to ecocide?

MAZHULIN: It's harder and harder to keep up your spirit, to keep up your morale, because there's no visible end of this, and people are just tired. I have to say, what's next? What should we expect? It's just... Stop it. You know, we had enough. Let us at least deal with these problems. Because, again, you say, like, what can we do about it? We start doing one thing and then another thing happen. So this side of the war, it's just yeah, that we wouldn't talk. When you think of a war, it's mostly like, what explosions, destruction, capturing of village or town. But they don't usually talk about ecology. They don't talk about nature, dont talk about how animals are hurt as well.

A serene nature scene in Ukraine, showcasing vibrant forests and a calm river in the landscape. In the interview, Artem Mazhulin reflects on the enduring beauty of Ukraine’s natural environment, emphasizing the importance of preserving these stunning ecosystems amidst challenging times. (Photo: Mike Nykytenko, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: So of course, there's the Desna River we've been talking about, but Russia has taken over a large amount of Ukrainian territory, and I understand that some of that includes some of the like national park areas. What's happening there? What's the concern with Russian troops advancing in those areas?

MAZHULIN: We don't know what's happening there. It's completely out of our control, out of Ukraine control. So how are they taking care of it? Whether they taking care at all? We don't know. I come from a small town in eastern Ukraine, near the smallest National Reserve Park. It's called a small town Dvorichna near Kharkiv Oblast. So now it's a front line, and this park is on the chalk mountains. It's like, kind of like a white cliffs of Dover if you know, in England, it's like hills of chalk. It's white. When you look at the picture, and it's July and it's all white, you think it's a... Wait, why is that snow? It's not snow, it's chalk. It's really unique and beautiful nature. That's where I grew up. That's where my parents used to live before their house got destroyed. So we're fighting to get this territory included in the list of Ukraine national parks. So finally, in 2009 the National Reserve Park was created. So the ecologist came, there was some administration. They started doing some tourist routes. They brought in some introduced some new animals. There was finally protection from uncontrolled hunting. So there was something happening there, and now it's the... No. It's not only it's. No, it's not technically occupied because, but it's very, very it's in the right, in the front line at the moment, and it's being constantly shelled. It's completely destroyed. No one is residing there, apart from the military. There's no civilian life there. And we don't know what's happening in that park, what happened to the animals, what happened to the to the fish, to the wildlife. We don't know. It's just uncontrolled, and it's just the part where I come from. And there's much bigger parks in the southern Ukraine, Kherson Oblast, other parts of Ukraine. We don't, we don't know.

DOERING: Artem, you're living essentially in a war zone. What does this war cost you personally?

MAZHULIN: Well, my parents, they lost a house. My hometown is half occupied. Why is it half occupied? Well, technically, let's say where my parents house is that village is occupied by Russia. It's on a very front line, and where I used to go to school, that part is Ukraine control, but it's just across the Oskil River, so it's still being shelled, and no one lives there like my school is completely destroyed. Everywhere I used to go as a teenager to hang out, or it's all destroyed now. So yeah, I now live in Kyiv, and I'm lucky enough to have a good job and doing something useful for my country.

DOERING: Artem Mazhulin is a freelance Ukrainian journalist based in Kyiv. Thank you so much.

MAZHULIN: Thank you. Thank you for taking interest. It was a pleasure to share. Thank you.

Related links:

- Check out the report by Artem Majhulin and Luke Harding for The Guardian

- Explore Greenpeace's interactive map detailing the environmental damage caused by the war in Ukraine

[MUSIC: B&B Project, No title-Original composition with quotes from folk songs Podolianochka" and "The Millet Was Sown"]

Huge Untapped Earth Energy

Pictured above is a geothermal feature in Mývatn Iceland. Geothermal energy close to the surface produces over a quarter of Iceland's total electricity. (Photo: Courtesy of Jamie Beard)

BELTRAN: Earth’s crust holds an abundant supply of heat that can be turned into electricity through geothermal technology. So far geothermal power generation has been mostly limited to volcanic areas like Iceland, where that heat is easy to access. But advances in deep drilling technology are revolutionizing the field worldwide. Back in 2006, research led by MIT for the national labs pointed to the huge opportunity of this deep geothermal as an always-on renewable that some say could be a game-changer for the climate. And recently the Interior Department green-lit the massive Fervo Energy project in Utah that should produce as much as 2 gigawatts, enough to power more than 2 million homes. Joining us now is Jamie Beard, the founder of Project InnerSpace, which aims to kickstart geothermal with drilling expertise from oil and gas. Jamie, welcome to Living on Earth!

BEARD: Hi, Paloma, thanks for having me.

BELTRAN: How would you describe the current state of geothermal energy in the United States?

BEARD: Well, the current state is really exciting. Geothermal has been pretty sleepy in the United States, and quite frankly, globally, if you look at geothermal development in the world, because geothermal is limited geographically in where you can do it in the hydrothermal sense, but also just because there has not been a lot of awareness about geothermal and the opportunity that it presents. And because of that, there's not been a whole lot of investment in the space. There's not been a whole lot of interested, you know, parties that want to do projects. And that's changing really rapidly in the United States, where now we have a lot of stakeholders interested in developing geothermal projects. Technology companies are engaging in geothermal wanting to produce geothermal energy to power data centers, and there's also a lot of interest coming out of the oil and gas industry now in geothermal. So we've kind of entered this renaissance period in the United States and, quite frankly, globally, for geothermal. So it's getting quite exciting.

BELTRAN: And what would you see as the potential for geothermal in our energy landscape, especially when it comes to the idea of base load power?

BEARD: Well, so most folks are aware when it comes to solar and wind, that they're intermittent, right? So they they're not on all the time. Geothermal doesn't have that issue. So geothermal, once you develop it, and you build a power plant, it's got a really high, what they call capacity factor, meaning how much it's on, and it doesn't really depend on when the sun is shining and when the wind is blowing, it's just always there. And you can even ramp it up and down, depending on energy demand at any given time. And that makes geothermal quite exciting when you look at particularly critical infrastructure and needs like data centers that they really depend on firm clean power, and they need a lot of it to service their demand. So geothermal as a base load is a really exciting prospect. Geothermal as a, you know, a heating and cooling application is also a really exciting prospect. So, you know, there are a lot of really interesting areas to explore in geothermal development.

Steam rising from a geothermal power plant cooling tower in Iceland. (Photo: Courtesy of Jamie Beard)

BELTRAN: So just to be clear, this is not your wwmother's backyard geothermal used for home heating and cooling. How deep are we talking about here for the next generation of geothermal?

BEARD: Yeah, so... If you are familiar with geothermal, you very well may be familiar with geothermal heating and cooling for houses, and that's been around. So a lot of folks have what they call shallow or direct use geothermal heating systems and cooling systems, and those are great. We should absolutely grow that space too. But that is indeed not what we're talking about when we're talking about next generation geothermal. Not necessarily. What we're talking about is drilling for geothermal energy at depths at least as deep as we drill for oil and gas currently. So you're talking about between 10 and 30,000 foot depths, so pretty deep and oil and gas drilling depths are likely as far as we need to go in terms of depth for the next decade or so. Eventually, geothermal we will need to advance to very deep, very hot resources if we want to keep advancing the ball. But there is an enormous amount of developable geothermal energy at depths that we're already used to drilling within the oil and gas industry. So let's go get those first right like that's the low hanging fruit that we need to aim for.

BELTRAN: You know, since this system involves deep drilling similar to the kind used in oil and gas extraction, what opportunities do you see for getting the fossil fuel industry on board with the clean energy transition?

BEARD: I think that is the single biggest opportunity that we have in geothermal right now is leveraging the capabilities, the technologies and the workforce of the oil and gas industry. Also the global scale of the oil and gas industry, and as we look to going fast in finding Climate Solutions and going fast in producing clean energy, the oil and gas industry, very well may be the golden ticket to that, right, because they already have a highly skilled and trained workforce that knows how to drill, right? And it's just a matter of turning a lot of that workforce and energy and technologies that are coming out of the oil and gas industry to drilling for heat instead of drilling for oil and gas. So, massive opportunity, and in terms of the size of that opportunity, I mean, it's, quite frankly, mind blowing. Geothermal is currently sitting at 1% in estimates for global energy demand. I mean, it's almost nothing in most estimates. But if the oil and gas industry were to throw in on geothermal and really engage and we started drilling geothermal wells at the rate that we currently drill for oil and gas wells, so that's about 70,000 wells globally that we drill for oil and gas right now. And if we were to do that for geothermal between now and say, 2050, geothermal could supply almost 80% of the world's electricity demand and more than 100% of the world's heat demand. That's huge. It's a massive potential impact, but that impact is 100% reliant on the oil and gas industry really helping grow and scale the technology over the coming decades.

Oil and gas drill rig, Pennsylvania. Organizations like Project InnerSpace research and advocate for an oil and gas drilling technology transfer into deep geothermal. (Photo: Courtesy of Jamie Beard)

BELTRAN: So, just to be clear, Jamie, for people who are not familiar with geothermal technology, it doesn't involve fossil fuels?

BEARD: Right! So with any energy technology, when you're drilling or building a power plant or manufacturing stuff you're gonna use energy to build that plant or to produce that energy project. So, unless we electrify everything, geothermal will probably produce some carbon emissions, because we're gonna have to build the plants, right? But geothermal, once it's developed and once it's producing power, it's using the heat that's in the earth to produce clean electricity and clean heat. So, in that way, it's a virtually carbon free clean energy source. Now, some next generation geothermal concepts actually adopt hydraulic fracturing, or fracking technology from the oil and gas industry. So, it's a technique where you're applying pressure to a well to essentially make more space in the rock. So you're cracking rocks open to make pore space in them. And if you're taking that technology from the oil and gas industry and transferring it into geothermal, you're leaving the oil and gas part behind and just using the technology to help the geothermal system work better.

BELTRAN: So Jamie, what makes you so confident we can scale up this technology?

Jamie Beard is the founder and executive director of Project InnerSpace. (Photo: Courtesy of Jamie Beard)

BEARD: So, I love the question, and my answer would be the shale boom. So if folks remember back, you know, 15 or so years ago when natural gas and the natural gas boom, what the oil and gas industry calls unconventionals, had not happened yet, and folks were talking about how we had reached peak oil and peak gas, and it was all downhill from here. And then all of the sudden, within a decade, what we call colloquially the shale boom, occurred, massive flourish of technological development, massive advances in the oil field and in natural gas production techniques. And we went from talking about peak oil and peak gas to the US becoming the world's leading natural gas and oil producer in the world, right? And that happened within a decade, right? And if we look at that transformation, I mean massive geopolitical transformation within a decade in the energy landscape, and we look at the capabilities of the oil and gas industry to transfer all of that energy and speed into geothermal, that's a really exciting prospect. We're talking about the next shale boom, but it's not gas and it's not oil, it's geothermal. We've done it before. We can do it again.

BELTRAN: Jamie Beard is the founder and executive director of Project InnerSpace. Jamie, thank you so much for joining us today.

BEARD: Oh, it's been such a pleasure. Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about Utah FORGE the laboratory sponsored by the Department of Energy (DOE) for developing Enhanced Geothermal Systems

- Utah Geological Survey | “Utah’s Energy Renaissance: Geothermal Energy Development in Utah”

- The Washington Post | “U.S. approves mega geothermal energy project in Utah"

- More on the Enhanced Geothermal Shot initiative

- Learn more about MIT’s seminal research paper on the potential of deep geothermal heat to power huge amounts of baseload electricity.

[MUSIC: Concordia, “Pavana alla venetiana” on Music for Mona Lisa, by J.A. Dalza, Metronome Records]

DOERING: Coming up, hardy mosses and other plants are thriving as Antarctica melts. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Concordia, “Pavana alla venetiana” on Music for Mona Lisa, by J.A. Dalza, Metronome Records]

BirdNote®: Rivers of Birds

Every year the Arctic Tern follows a migratory pattern of 50,000 miles, one of the longest routes for any bird. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BELTRAN: This time of year in the Northern Hemisphere you might look up to see V formations of geese flying south. Or, you could picture it this way, as Mary McCann reports for BirdNote.

BirdNote®

Rivers of Birds - Arctic Tern

[Sounds of migrating birds]

Imagine yourself in the stratosphere, looking down on North America. In spring and fall, you’ll see what look like huge “rivers” of ducks, seabirds, shorebirds, raptors, and songbirds. Migrants are moving along the four major North American flyways. In the spring, these “rivers” of birds flow north. At the end of the breeding season, the “rivers” flow south.

The Arctic Tern has the ability to spend most of its migration gliding rather than flapping its wings. (Photo: Joseph Slocum)

After spending the winter in the southern tier of states or Central America—or even as far away as South America—millions of birds return each spring to the northern latitudes. One of the world champions of long-distance migration is the Arctic Tern. [Calls of Arctic Terns]

Arctic Terns nest across the far northern reaches of the continent during our summer, then fly south to Antarctica for the rest of the year. Some will circle the polar ice-pack before heading north again, completing a total round trip of up to 50,000 miles. Every year. [Calls of Arctic Terns over the sound of ocean waves]

###

Adapted from a script written by Frances Wood

Sounds of the migrating geese provided by Martyn Stewart at Naturesound.org.

Call of the Arctic Tern used with permission from Kevin Colver from the Field Guide to Bird Songs, Western Region.

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and produced by John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2019 Tune In to Nature.org March 2019 Narrator: Mary McCann

https://www.birdnote.org/show/rivers-birds

BELTRAN: For pictures and more, flap on over to the Living on Earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- BirdNote® | "Rivers of Birds"

- Audobon | "Guide to North American Birds: Arctic Tern"

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Woodsong Wanderlust” on Pure Hammered Dulcimer, by Joshua Messick, self-published/at joshuamessick.com]

The Greening of Antarctica

Although you may think of Antarctica as void of green, its peninsula is actually a habitat for moss. (Photo: Matthew Amesbury)

DOERING: The impact of climate change in Antarctica can be dramatic, with huge ice shelves breaking up and glaciers collapsing into the sea. But ice isn’t the only thing that’s changing about this frozen world. Earlier this month, a study published in the journal Nature Geoscience revealed that parts of the icy white continent are rapidly greening as plants thrive, potentially because of the significant warming that’s happening at the poles. The researchers analyzed satellite images of the Antarctic Peninsula, that little tentacle reaching towards the tip of South America. Here to discuss the study findings is the co-lead author, Dr. Olly Bartlett, a senior lecturer in remote sensing and geography at the University of Hertfordshire in the UK. Welcome to Living on Earth!

BARTLETT: Thank you very much for having me.

DOERING: So what did you find in this study?

BARTLETT: So the main finding of our study is that vegetation cover on the Antarctic Peninsula has increased over 10 times since 1986, and recently, so from 2016 to 2021, that rate has increased compared to the background rate. So recently, this greening has accelerated. And in terms of football pitches — sorry, I have to lean into my Britishness —

DOERING: Soccer fields.

A new study indicates that the amount of vegetation on the Antarctic Peninsula has increased 10x in the past 40 years. (Photo: Matthew Amesbury)

BARTLETT: Soccer fields. There you go. Yep. So 100 said soccer fields in 1986 so 1515 soccer fields in 2021, and the rates, to throw in a completely different comparison an area. So the rates in the most recent part of the study is well, 54 football pitches a year, if we keep up with that, or one Vatican City.

DOERING: Oh, one Vatican City every single year?

BARTLETT: One Vatican City a year. Yeah.

DOERING: So what do you think is going on there?

BARTLETT: When we were doing a study, there were multiple times where we didn't believe the numbers, multiple times where we were looking and thinking, nope, this can't be right. Run it again. Run it again, run it again. And so we are confident that these numbers, what we're seeing, is real, and what's happening is we see the mostly moss dominated ecosystems of the peninsula are expanding laterally, so out horizontally. Part of it is also moss that has been there previously but has now grown in health to the extent where it has become so verdant, so green, that it is now identifiable from space when it may not have been in previous years. So, two parts of the signal, one part is this lateral expanse of vegetation, another part vegetation that was there before, but maybe not as green, not as healthy, has increased in its health, in its verdancy, over the study period, and now we're seeing this from space.

DOERING: I have to say that I didn't even realize that Antarctica had green plants on it. We see pictures of penguins, and they're standing there huddled against the freezing Antarctic winters, just surrounded by ice. So tell me more about this amazing ecosystem that exists in Antarctica of moss and other plants.

Dr. Bartlett’s study analyzed red, green, and near infrared bands of light captured by satellites. Plants reflect different amounts of these types of light. In the top half of the photo, you can see what the arial shots look like to the human eye. The bottom half shows the near infrared bands of light usually invisible to us. (Photo: Worldview-2/DigitalGlobe/TheAuthors)

BARTLETT: A lot of the ecosystems we've been measuring are moss, there are lichens, there are liverworts. Now these sorts of plants, they can colonize bare rock surfaces. So when ice moves out of an area, and the conditions are suitable, mosses, lichens. These plants can grow on bare rock. They're colonizer plants. They're the pioneers, if you like, of an ecosystem. There are only two vascular plants, so what we'd think of as a standard flowering plant, if you like, currently across the Antarctic Peninsula, but as more people go to visit the peninsula, that includes scientists like us on the study, but also tourists, there's more chance of bringing seeds and spores from outside and getting them into the ecosystem.

DOERING: Yeah, so that sounds like a real risk for the few native plants that are there.

BARTLETT: Yeah, for sure, and that's one of the main things we're highlighting with our study, is that as this vegetation, as these colonizer plants, these pioneers, as they're growing and getting more comfortable, they're creating the conditions for higher plants and other species to have an easier time of living in one of the harshest places on the planet. So there's real biodiversity implications with this greening rate that we're seeing with this expansion of vegetation across the peninsula.

DOERING: What could we do to prevent the spread of invasive species in Antarctica?

BARTLETT: Yeah, great question. So in terms of the potential for non native species, which can potentially be invasive if they're able to out compete local species. Well, to some extent, Antarctic Peninsula and Antarctica is very windy, nature is going to find a way to get new seeds, new spores, into the continent, into the peninsula, as there are migrating birds as well, that travel from very long distances, from all across the world, down to Antarctica, they're always going to have the potential to bring stuff with them, but in terms of people that are going down there, so scientists and tourists who go to visit on cruises and etc, having really important biosecurity measures, For example, if you go to Australia or New Zealand, they have really tight biosecurity measures in customs, making sure that the kind of kit that you bring that you're going to wear in outdoorsy settings, so like hiking boots, tents, maybe fishing gear that has to be clean. And if you're going down to work in Antarctica, boots, gear, all the stuff that you're going to be wearing that you've bought with you have to be cleaned thoroughly before you're taking them out onto this expanse of lands that may or never have seen the kind of seeds and certain things that you may bring with you.

Dr. Olly Bartlett is a Senior Lecturer in Remote Sensing and Geography at University of Hertfordshire. (Photo: Olly Bartlett)

DOERING: So what exactly is happening there that's allowing this vegetation, these mosses and lichens and liverworts, to spread?

BARTLETT: So Antarctica, much like the Arctic, is at the front line of climate change. As the planet warms, it's well known that the polar regions are warming much more quickly. Now our study, it's really important to say we've seen what we've seen. That's what I do as a remote sensing scientist. I make some observations, I make some measurements, and I report them. W hat we haven't done is attributed any cause to this. Now you can think of some obvious things that are likely to cause this, like increasing temperatures. Most things on this planet do like it a bit warmer than the general conditions that you would get in the poles. Also, moisture availability. So with the reduction in sea ice cover, you're able to free up moisture from the ocean that's sort of locked in by the sea ice underneath it to the atmosphere, where it can move into or onto land and nourish plants that way. So there's two possible causes, both related to a changing climate, then also, with glaciers receding, as is happening across the world, they expose new land which these colonizer plants are able to move into and occupy.

DOERING: Are there any potential impacts on the rate of glacial melting because of these plants growing and spreading there?

BARTLETT: This is often a question that comes up when we see land system change in front of glaciers or in front of ice. When I say land system change, I'm talking about the retention of heat in an area near a glacier. And when we change the color of an area, we change how much heat it directly reflects back that comes in from the sun. So if we were to darken an area, replace snow with vegetation, for example, then we would expect to retain more heat. However, at the scale of our study and where it is and the Antarctic Peninsula is still very much mostly ice and rock, this change in vegetation is very unlikely to retain heat to the extent that it would influence local ice retreat. Might retain heat to the extent where it makes it easier for the ecosystem to develop. That's possible. But in terms of glacial retreat, what's more important in terms of increasing ice melt, is that change from sea ice to ocean on a bigger scale, retaining heat locally to increase the amount of energy available to melt ice, but also on the glaciers themselves, when the surface of the ice gets darker as it melts.

Dr. Bartlett was co-lead author on the study with Dr. Tom Roland. Here they are together in Peru. (Photo: Ellie Fox)

DOERING: Can you project a little bit into the future for us? I know it might be hard to do from this one study, but if this change, this kind of trend line continues, what do you think Antarctica might look like in 50 years or so?

BARTLETT: So we're not expecting Antarctica to be covered in trees or anything like that in 50 years, and to be honest, probably not even shrubs. But what we are potentially going to see is the connectivity between the different bio geographic regions across Antarctica. So not just the peninsula, increasing. So Antarctica is made up of different bio geographical regions which have their own unique biodiversity, their own unique ecosystems. Now if those ecosystems expand and sort of get closer to each other, and it's not so hard for material to move between them. More interconnected, then we could likely see an erosion of biodiversity between these unique biogeographic regions. We would expect to see, as ice goes back, more land becomes available, and we have this increasing greening trend that land to become greener as the ice retreats.

DOERING: What do you hope people take away from your research?

BARTLETT: To some extent, I do hope it causes some kind of surprise or shock to show that even this isolated, remote, last wilderness, really symbolic place on our planet. Okay, the Antarctic has captivated us ever since we've known of its existence, and now it's fundamentally changing across many parts of the system that people see another one and think, okay, if you didn't need waking up before, maybe it's a waking up now. Of we need some real, meaningful change on climate, and those who have the power and the authority to do so are able to start acting to ultimately cutting out greenhouse gas emissions.

DOERING: Dr. Olly Bartlett is a senior lecturer in remote sensing and geography at the University of Hertfordshire in the UK. Thank you so much.

BARTLETT: Thank you so much for having me. It's been a pleasure to talk with you.

Related links:

- Read the original study

- Learn more about invasive species

- Learn more about Antarctic moss

[MUSIC: Barbara Higbie, “Stillness” on Murmuration, by Barbara Higbie, Slow Baby Music BMI/Raging Hormones Music]

BELTRAN: Next week on Living on Earth, One of our favorite authors, Sy Montgomery, is back with a book about her feathered family.

MONTGOMERY: We're just starting to decode the complexity of their chicken language. For example, we do know that chickens have a way of telling other chickens, not just that there's a predator, but is it coming on land or by air? Is it close or is it far? But they say much more than that, they'll also say not just here's food but here's food that you're really gonna like versus, you know, here's some food you might want to have it. And a friend of mine discovered that her chicken had a name for her. And she was saying that there was one chicken in particular her favorite chicken, Tilly who would say something, but only when she was around. And we figured out that that was the name that Tilly had given her her, her name, by the way, was almost like a trumpet. It went like ba, ba, ba, BAAA I mean it was a special announcement like the queen is coming, get ready and Tilly is gone now. But Tilly taught that name to other chickens who still speak her name.

BELTRAN: Sy Montgomery, next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: No em pingo D’Agua, “Salvador” on Contemporary Instrumental Music From Brazeil, by Egberto Gismonti, A Windham Hill Sampler – Windham Hill Records]

BELTRAN: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Kayla Bradley, Josh Croom, Daniela Faria. Mehak Gagneja, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Nana Mohammed, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Andrew Skerritt, and El Wilson. We bid a fond farewell to Jolanda Omari and wish you a happy retirement! And thanks to Sommer Heyman for all your hard work.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Allison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and YouTube Music, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth