March 3, 2023

Air Date: March 3, 2023

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Dioxin Concerns After Train Crash

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

The train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio last month led to a controlled release and burn of vinyl chloride, which can produce the neurotoxin dioxin. Julie Grant, a reporter for Allegheny Front, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss local concern about the potential dangers of dioxin contamination in their communities. (08:33)

Dolphins May Use Corals for Skin Care

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

While diving in the Red Sea, researchers noticed bottlenose dolphins taking turns brushing their bodies against certain corals. As Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports, scientists hypothesize that it helps the dolphins maintain healthy skin. (01:58)

CO2 Pipeline Safety Risks

View the page for this story

Proponents of carbon capture and storage hope to expand a network of pipelines that transport carbon dioxide from source to sink so that it can’t get into the atmosphere to warm the planet. But these pipelines carry high-pressure CO2 that can be dangerous, even lethal. Bill Caram, the executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, explains these safety concerns. (13:07)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, contributor Peter Dykstra and Host Jenni Doering discuss the impressive clean energy achievement of a small town in France. Next, they consider a study about growing threats to narwhals from shrinking Arctic sea ice before going back in history for a look at the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899. (04:11)

BirdNote®: Sound Escapes – Learning to Be a Deep Listener

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

Sound recordist Gordon Hempton brings us the sounds of the Amazon in this BirdNote® from Ashley Ahearn. (01:51)

Cliff Hanger

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Along the east coast of the Falklands, an agile cormorant soars and dives among the cliffs. Living on Earth's Explorer-in-Residence, Mark Seth Lender, reflects on the empire of this majestic but much-maligned bird. (03:53)

Climate Change and Mating

View the page for this story

Showy traits like dark pigmentation on a dragonfly’s wings or a lion’s big, dark mane play a key role in how some animals choose a mate. New research suggests that climate change is making some classically attractive traits more difficult to pull off. Evolutionary ecologist Michael Moore at the University of Colorado Denver joins Host Bobby Bascomb to share more. (12:21)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

230303 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Jenni Doering

GUESTS: Bill Caram, Julie Grant, Michael Moore

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

Residents near the train derailment in Ohio worry that dioxins may be in the soot that is falling on their homes.

GRANT: From what toxicologists and chemists are saying is if dioxins were created it would attach to the soot that was created in the explosion and kind of fall to the ground. And there is the question of what is in the soot. And I think that's one of the concerns that people still have.

DOERING: Also, climate change is changing what traits are advantageous in nature.

MOORE: There’s some interesting research in birds where some of their breeding plumage is starting to change as a result of it being too warm. Lions that really have big dark manes also tend to overheat even though those big dark manes are beneficial to the male lions.

DOERING: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Dioxin Concerns After Train Crash

An image from drone video taken on February 5, 2023 of the Norfolk Southern train derailment near East Palestine, Ohio. (Photo: National Transportation Safety Board, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The Norfolk Southern train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio last month released a cocktail of toxic chemicals include vinyl chloride and benzene into the local environment. The spill contaminated the soil and surrounding waterways, and an estimated 40,000 fish have died as a result. And now scientists and local residents are raising the alarm about a new concern- soot that may contain dioxin. To avoid an explosion, Norfolk Southern did a controlled release and burn of some vinyl chloride but heating the chemical can change its chemistry to create dioxin, a neurotoxin used in Agent Orange during the Vietnam War. Soot that may contain dioxin has settled on homes and farmland for miles around the disaster site, raising concerns for the health of the people and farm animals that were exposed. EPA initially said it would not test for dioxins, saying they didn’t have baseline data to make an accurate comparison to levels before the accident. But the agency recently changed course and has now directed Norfolk Southern to begin testing for dioxins and will compare findings to dioxin levels outside the area affected by the accident. Reporter Julie Grant has been covering the story for Allegheny Front and joins me now for more. Julie Welcome to Living on Earth!

GRANT: Hi, thanks.

BASCOMB: What are the concerns for both people and animals exposed to this soot that potentially contains dioxin?

GRANT: Dioxins are ubiquitous and exist in the environment at low levels. We're breathing them in all the time. But at higher levels, they can be toxic, they interfere with hormones can cause cancer, damage the immune system cause reproductive and developmental problems. That's all coming straight from the Environmental Protection Agency.

BASCOMB: Well, you open your recent story in the Allegheny front with David Anderson, a local farmer, can you tell us about him, please and what he went through?

A drone image above David Anderson's farm in Beaver County, Pa., 4.2 miles from the East Palestine, Ohio, train derailment, on February 6, 2023, when Norfolk Southern did a controlled release and burn of vinyl chloride from some of the wrecked train cars. (Photo: Courtesy of David Anderson)

GRANT: Yeah, so David and Elaine Anderson, this was kind of their dream home. She wanted to live somewhere that was like the Waltons, she said and so they've created this and what they call Echo Valley Farm, because it's this small valley, about 4.2 miles from the site of the train derailment. They have seven children, a few of them are adults now, but they all still gather at the farm a lot. And about 100 animals, they said 25 cows, that cattle I guess that they grow for. He called it an Angus cross it's Angus cattle crossed with another kind and they sell those for meat. They also have chickens that they raise for eggs for their own family and meats, but they also sell those. And you know, it's just a lovely spot. They have many ducks, they have three adorable donkeys that are super friendly and three dogs. And you know, like everyone else, when they heard that East Palestine was being evacuated mandatory evacuation they were on watch that this vinyl chloride was about to be burned, people were paying attention. He's a retired Air Traffic Controller and what he called himself a wind nerd and he sent up his drone. He's watching very closely the winds to see if they would be safe at the farm. He sent up a drone and saw this huge cloud. You can see some of these kinds of photos online. It's just this big dark cloud in the sky and it kind of looks like it's spreading all around the region. And they went in to eat dinner, and from what Elaine said, she said, Gosh, the mustard is so spicy, wonder why. And then, after dinner, one of their sons went outside to get water or something and was like, oh my gosh, the air is smells so bad out here and when they walked outside, they immediately knew what was what was going on. How Dave Anderson explained it was you know, our eyes were burning, our tongues were burning. We realized he said, look, we gotta go and they all just got in the car, they had to leave the animals drove seven miles north to where his oldest daughter who's pregnant lives. And then when they came back to the farm a few days later, I mean he came back to feed the animals, but when the whole family came back a few days later, that's when they found the soot on things and started worrying about how that was going to affect the animals and their ability to grow a garden and their ability to sell the meat from their animals, that kind of thing.

USEPA ordered Norfolk Southern to test for dioxins in the area of the train derailment after pressure from the community. https://t.co/Ix9Qd2Zzys

— The Allegheny Front (@AlleghenyFront) March 2, 2023

BASCOMB: And dioxins, from what I understand can bioaccumulate in animals, so a cow that was exposed today axon might actually be a risk for people that could eat that beef later on, and even eggs from chickens that were exposed. Can you tell us more about that?

GRANT: Yeah, so I talked with Murray McBride. He's an environmental toxicologist at Cornell University he's a professor emeritus there. He thinks that the animals would be less likely to have breathe this in. The bigger concern, he says is this sort of surface contamination and, you know, once it rains, that goes into the ground. So for like a free range chicken that's out pecking and getting its food from the ground, that can be really dangerous if there is dioxin in the soil they can take that in. From my understanding, dioxins attach to fat, and so it would attach to the fat of the animal and thus would show up in chickens eggs, it would show up in the meat if people were eating those chickens. And that same idea that dioxin attaches to fat also means that it can wind up in milk, it can wind up in butter. Interestingly, from what Professor McBride said, well, it's in the ground, new plants that are growing up from that ground don't actually uptake the dioxin. So new grass in the spring, even if the soils in East Palestine in that area are contaminated the new grass, you know, would not grow with dioxin in it. So cows could graze that grass and not necessarily take up dioxin, even if there's dioxin in the soil. Now, you know, there is a caveat there, which is if it's dry cows can kick up the soil And if it's contaminated, the dust from the soil can get on the grass and then if they're eating that grass, they can still get contaminated. But there is at least some modicum of good news there that new plants could grow and be clean.

One of the donkeys that was left behind when the family evacuated, shown here on February 15, 2023. (Photo: Julie Grant, The Allegheny Front)

BASCOMB: And as you mentioned, the plants that grow there aren't necessarily going to uptake you know, some of these toxins, the dioxin, for example, but from what I understand some vegetables that we might grow are more concerning than others. Can you tell us about that?

GRANT: Yeah, the way Professor McBride described this, to me was like, you could grow tomatoes those grow above ground and those should be safe and those would be fine even if the soil is contaminated with dioxin. Something like lettuce that's growing close to the ground, he might be more careful. He said, definitely, I would wash it but it might be hard to get that all off if the ground was contaminated. And he said, I definitely would not be growing a root vegetable like carrots or something that's kind of surrounded by the soil because if there was dioxin in the soil, it's there growing in that problematic environment.

BASCOMB: Well, let's shift gears a little bit and talk about another story that you've been reporting on and that's disposing of the water and the firefighting foam that was used to put out the fire after the initial burn of the vinyl chloride. From what I understand there's only a handful of facilities that can accept this sort of toxic waste, especially from out of state. How are the communities around those areas responding?

David Anderson, standing near his cattle on February 15, 2023, says he wants to know if his beef is safe to eat. (Photo: Julie Grant, The Allegheny Front)

GRANT: So from my understanding, some of the waste was sent to Texas and some of the waste was sent to a facility in Michigan, and public officials in those communities expressed that they were not aware that this was coming, and we're not happy about it. Some of the waste from Michigan actually turned around and came back to Ohio. More recently, the regulators have said they have identified facilities closer three in Ohio and one in Indiana that will accept this waste. But anyone who's in one of these communities, for example, in Northwestern Ohio, where some of the liquid waste, I think is going and will be pumped into an underground injection well. Now that injection well, I'm not sure what they're taking, but there are plenty of class two injection wells around Ohio, lots and lots of them that are taking waste from fracking that's done in the area for natural gas and a lot of that is radioactive, and it's being sent into underground injection wells that are somewhat similar to this one. And we don't hear people all up in arms about that because nobody's paying attention most of the time. Here and there people pay attention. But now this is putting attention on this issue, like we're creating all this waste, where are we putting it?

BASCOMB: Julie Grant is a reporter with the Allegheny Front. Julie, thanks so much for your time today.

GRANT: You're welcome. Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read more of Julie Grant’s stories for Allegheny Front

- The Washington Post | “EPA Orders Testing for Highly Toxic Dioxins at Ohio Derailment Site”

- EPA | “EPA Requires Norfolk Southern to Sample for Dioxins in East Palestine”

- Democracy Now | “Bomb Train: Calls Grow for New Laws on Rail Safety After Toxic Disaster in East Palestine, Ohio”

- Review EPA’s Soil Sampling data

- EPA "EPA Requires Norfolk Southern to Sample for Dioxins in East Palestine"

[MUSIC: Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited/Wadada Leo Smith and N’Da Kulture, “Regal Tone/Jealousy” on Dreams and Secrets, by Wadada Leo Smith & Thomas Mapfumo, ANON0101]

BASCOMB: Coming up after the break, the hazards of transporting carbon dioxide via pipelines but first this Note on Emerging Science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Dolphins May Use Corals for Skin Care

Dolphins may use corals to help keep their skin healthy. (Photo: photo_teria on Pixnio)

LYMAN: While diving in the Red Sea, researchers from the University of Zurich often noticed Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins lining up to take turns brushing their bodies against certain corals or sea sponges. The scientists reported in iScience that the dolphins may use corals and sponges for possible medicinal purposes, and hypothesized that the rubbing could help dolphins maintain healthy skin. Recordings of the dolphins shows members of the pod utilizing corals like a bath brush, swimming by to rub various parts of their bodies. The researchers said the dolphins appear to pick out certain corals, primarily rubbing against gorgonian corals (Rumphella aggregata), leather corals (Sarcophyton sp.), and a species of sea sponge in the genus Ircinia. The scientists analyzed one-centimeter slices of wild corals and sponges, and identified 17 chemical compounds, including 10 with antibacterial or antimicrobial activity. Researchers hypothesize that as the dolphins rub against the corals they release compounds into the water that help protect the animals from skin irritations or infections. Dolphins are not unique in seeking out nature’s pharmacy. Scientists have observed self-medicating behaviors in chimps, certain bird species, and elephants. Future research with dolphins might try to determin if the dolphins are utilizing corals and sponges to prevent skin problems, or if they’re treating active skin infections. The researchers also plan to figure out if dolphins prefer to rub specific body parts on specific corals. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Science News | “These Dolphins May Turn to Corals for Skin Care”

- Read the study

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jan Harbeck Live Jive Jungle, “Elevate” on Stunt Records Compilation Vol. 25, by J. Harbeck, Sundance Music]

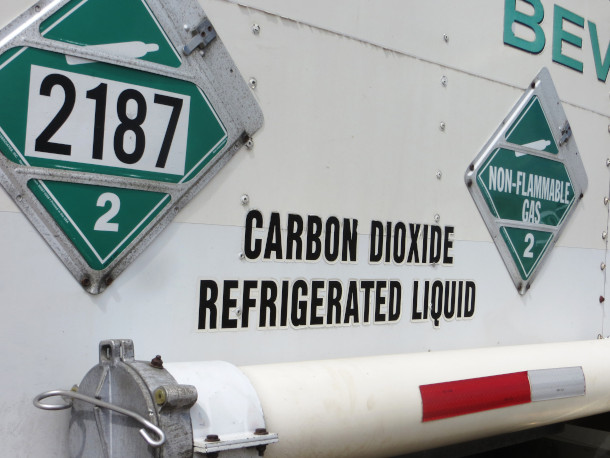

CO2 Pipeline Safety Risks

Refrigerated carbon dioxide used in firefighting. Carbon dioxide can be transported in a gaseous, liquid, or supercritical state. (Photo: Washington State Department of Ecology, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Before the break we talked about the unfolding hazards of transporting toxic chemicals via train. Pipelines can also be a source of spills for everything from oil and natural gas to carbon dioxide from carbon capture and storage technology. Carbon capture and storage has long been a hope of fossil fuel companies and carbon heavy industries like power plants and factories. It allows industry to emit carbon dioxide, business as usual, and safely store it below ground where it can’t warm the planet as a greenhouse gas. Proponents see carbon capture and storage as another tool in the fight against climate change but critics say it’s a relatively new technology with a lot of unknowns. And it’s expensive though tax incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act and the bipartisan Infrastructure Bill could make carbon capture and storage more economically feasible. Another concern is safety, especially when it comes to pipelines transporting carbon dioxide from where it is produced to where it will be stored. For more I’m joined now by Bill Caram, the executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust. Welcome to Living on Earth, Bill!

CARAM: Thanks for having me.

DOERING: So what exactly is the carbon dioxide that would be moving through these pipelines? Can you describe what state it's in?

CARAM: Yeah. If everyone remembers back from high school science class, you can have a gaseous state, you can have a liquid state, you can have a solid state. CO2, carbon dioxide, can be moved in a gaseous or a liquid state. What maybe you didn't cover in your high school science class, there's another phase called a supercritical fluid. And that is actually where carbon dioxide is regulated, and is often moved through pipelines.

DOERING: So when we talk about oil and gas pipelines, you know, we worry about these images when a horrific accident happens and there's a pipeline rupture, and we might see the oil spilling out, you know, maybe there's even flames. It's very visible, it's very obvious the damage to the environment from that. But we're talking about moving CO2 and I'm wondering about the dangers there. You know, maybe they're not quite as obviously visible in photos, but what could happen if we're moving CO2 through pipelines like this?

Site of the pipeline rupture in Satartia, Mississippi. Fifty of the town’s two hundred residents sought medical attention after their exposure to the carbon dioxide that was released. (Photo: Mississippi Emergency Management Agency, PHMSA.gov)

CARAM: CO2 really is its own set of risks. It's really unique. It's not going to explode, there's a little bit of risk to water, but not in the way that the hydrocarbons have. And its threat is as an asphyxiant. It displaces oxygen. CO2 is heavier than air. So methane is lighter than air, and so when a natural gas pipeline ruptures, the methane will dissipate, whereas CO2 will sink and stay close to the ground. And because they're often moved in this high pressure, dense phase, you can have a lot of CO2 emptying a pipeline all at once in a rupture. And that can lead to this dense cloud staying close to the ground and migrating in the direction of a light wind or going downhill along the topography of an area. And it can settle in low lying areas at dangerous and even lethal concentrations.

DOERING: Tell me more about that. What does that mean, potentially, if there's a village or homes in a low valley where the CO2 sinks down and collects?

CARAM: So we saw this happen in a community called Satartia Mississippi in 2020. A pipeline that ran near that community carrying CO2–by Denbury–there was a landslide and the pipeline ruptured. The valves are 20 miles apart, 10 miles apart. And so all of that CO2 comes out of the pipeline. And it's odorless and invisible. It slowly made its way to the community of Satartia. Now, the operator, they thought that the community was far enough away from the pipeline that it would never be an issue and so it wasn't part of their, you know, emergency response plans. They didn't consider it a high consequence area of the pipeline. But it did, in fact, reach the community and it sent 50 people to the hospital. The community is only 200 people. Some were very sick. It's amazing that nobody died. The first responders were true heroes. They donned scuba gear, they didn't really know what was happening. But they figured out they needed scuba gear. Their cars weren't operating because there wasn't enough oxygen for their internal combustion engines.

Lake Nyos in Cameroon, Africa. A natural release of CO2 gas from the lake killed 1,700 people living in the low-lying area nearby. (Photo: jbdodane, Flickr, CC BY–NC 2.0)

DOERING: Oh my gosh.

CARAM: So they put on scuba gear, and they kind of ran into this white cloud. And we're pulling people out who had, you know, were walking in circles, were having seizures, all of these signs of this high CO2 exposure. So we had 50 people go to the hospital. The hospital didn't really know what to do with them, sent them home. A lot of them came back the next day, and they finally did some blood work and they just had these super high levels of CO2 in their blood. We're now three years later and there's still some folks that are feeling the effects of that today.

DOERING: Are there any other examples of instances where CO2 leaked and people did perish?

CARAM: So in the 80s there was a large natural release of CO2 from a lake in Cameroon, Africa, and it killed every oxygen breathing person and animal within 16 miles of the lake in kind of a circle around it and it ended up being 1,700 people died. And that's when the United States Congress told the federal regulator of pipelines, "Hey, you need to start regulating CO2 pipelines." To be clear, the amount of CO2 they've estimated that is much larger than would come out of any kind of pipeline failure at the types of pipelines we're talking about in the US.

DOERING: But what kinds of carbon dioxide pipeline projects are currently proposed in the US?

CARAM: So there are a number of projects that are proposed. Currently, there are a number of projects announced in the Midwest that would capture CO2 from ethanol production facilities and move them to various sequestration sites in the upper Midwest. Ethanol is kind of a low hanging fruit for carbon capture and sequestration. It's relatively inexpensive to capture CO2 from those facilities and it ends up being relatively clean carbon dioxide without a lot of impurities. We also have of a project further west that is looking at converting an existing pipeline to carry CO2 to a sequestration site. There's also a number of projects announced down in the Gulf states where they would be sequestering CO2 in the Gulf of Mexico and under–under the sea floor. And as we move away from ethanol and into, you know, power plants and things like that, impurities in the CO2 are going to become much more of an issue. So right now we have about 5,000 miles of CO2 pipelines. They're in really rural areas. The roadmap looks like we're talking 100,000 miles or considerably more. I fear they will be much closer to people's homes and closer to communities than they are right now.

The Petra Nova carbon capture system in Texas. Pipelines move the CO2 collected at carbon capture sites to facilities where it can be used. (Photo: US DOE, energy.gov, public domain)

DOERING: Are these pipelines above ground, underground? What are we talking about here?

CARAM: They are buried. Depends on a lot of variables in the regulations, but you know, three to five feet below ground. The fact that it's buried doesn't necessarily make it safer, although it does keep it from maybe some excavation damage or, or somebody driving into it in a car accident and protects it that way. But in the case of a rupture, you know, whether it's buried three feet or five feet, it's going to be a pretty violent rupture.

DOERING: So you mentioned that in this Satartia incident that happened a couple years ago, it wasn't really clear the risks to the community of Satartia, if there was going to be a pipeline leak. Why is that? And how good is the modeling in terms of like, you know, if a pipeline breaks at this particular point, and it's carrying CO2, what the impact could be.

CARAM: So we have pretty good models and formulas to figure out the potential impact radius, the area around the pipeline that would be impacted by a failure, for hydrocarbon pipelines, for oil and gas pipelines. Because CO2 is heavier than air and it doesn't ignite, it can move kind of long distances away from the pipeline in kind of unpredictable ways at these dangerous and lethal concentrations. And so how do we figure out which pipelines have the potential to impact a community? There's a lot of work to be done in this area. We don't have a model that we can just point to and say, "Use that model, run it on your whole pipeline and see where it could impact communities." There's a lot of R&D being done on that right now but it's an unanswered question of the best way to do it. And this is important because once an area of a pipeline is determined to have the ability to impact a community, the operator has higher safety standards for that section of pipeline. More inspections, you know, higher quality of pipe. And so if we're not measuring that properly, we can have long sections of pipe that might impact a community that aren't being inspected as often as they should and aren't built to the high specifications they should. It's definitely one of those things that keeps me up at night about these new CO2 pipelines.

DOT office in Washington, DC. PHMSA, one of the Department of Transportation’s operating bodies, is responsible for regulating hazardous materials transportation (Photo: D Ramey Logan, US Department of Transportation, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

DOERING: What's the top line concern here for your group, for the Pipeline Safety Trust?

CARAM: Our main concern is that the regulations are really far behind. The federal regulator is PHMSA, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, is part of the Department of Transportation. And when Congress asked them to start regulating CO2 pipelines in the 80s, you know, knowing that there were so few miles and that they were relatively rural, they just kind of added "and CO2" on to the existing hazardous liquid pipeline regulations. And CO2 poses unique risks and it requires unique regulations. And we don't have those. And we have kind of big regulatory gaps. So right now, it's only regulated if it's a supercritical fluid, that unique high pressure, high temperature state if it's a liquid, or if it's a gas it's not regulated at all. We don't have any regulations around adding an odorant so that people would know when there's been a release. So a lot of people don't know this, but natural gas has an odorant added to it so that you get that rotten egg smell. You wouldn't smell it otherwise. And so we would love to see an odorant added so communities will know when there's been a CO2 release. There's also a lot of issues around impurities in CO2. Even just having water in CO2 leads to carbonic acid, which just eats through steel pipelines. The natural sources where operators are getting the CO2 from now is very dry. But when we start getting it from these other sources like power plants, they are going to start having a lot of impurities and we're going to have to deal with corrosion in a way that the operators aren't used to right now on CO2 pipelines, and the regulations just don't cover it at all. One interesting thing about these pipelines: a natural gas pipeline needs to go to a federal agency for approval of the siting of the pipeline, the route that it takes. There is not that requirement for any liquid line, including a CO2 pipeline. Each state has its own rules, so these local governments and state governments because PHMSA regulates the safety, they can't make safety–kind of–any part of their permit. They can't say,

DOERING: Oh wow.

CARAM: Well, it's not safe to be that close to a school," or "You have to show us what kind of safety precautions you're taking if you're going to be that close to a school. They're preempted from being able to do that.

DOERING: That's incredible. What you're describing is that, just the system of regulation that we've created leaves really huge gaps in some areas. So can you clarify for me, what are the regulations right now about, say, distance from a school?

“A PST report identified regulatory gaps and dozens of groups [then] asked the U.S. Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration to pause carbon capture permits until new, federal safety regulations are created." https://t.co/Z7UplmpDkA

— Pipeline Safety Trust (@pstrust) January 26, 2023

CARAM: There are none. You know, the operator has a certain distance around their right of way, but there's no law that says you can't build, you know, right up to a, a pipeline to the right of way.

DOERING: Wow. It makes me wonder, you know, if–if some of the same regulators are involved in regulating railroads, and we've seen what just happened recently in East Palestine and how potentially a lack of appropriate regulations or oversight may have contributed to that, makes me a little concerned about what could happen with pipelines, including carbon dioxide pipelines.

CARAM: It's a fair concern and it's one that I share with you. These regulatory bodies, they are passionate about their jobs and they want to keep people safe. But they're understaffed and they're underfunded and they really don't have the resources they need to appropriately regulate their industries. And so what they're kind of forced to do is rely on the industry for their technical expertise and helping them write the regulations.

DOERING: And what have you heard from PHMSA and DOT about the possibility of putting in place some of these regulations?

CARAM: Well we were really thrilled to hear PHMSA announce last May that they are undertaking a rulemaking, meaning that they are going to put in place new regulations on these pipelines. We don't know how long that will take. It's generally a multiple year process. And we really don't know how comprehensive those rules will be. And we certainly hope that they address all of the shortcomings that we've identified.

DOERING: Bill Caram is the executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust. Thank you so much, Bill.

CARAM: Thank you, Jenni.

Related links:

- Huffington Post | “The Gassing of Satartia”

- Click here to read reports and fact sheets from the Pipeline Safety Trust about CO2 pipelines

- Find out what pipelines run through your state with the National Pipeline Mapping System interactive tool

- Learn about the most recent pipeline failures using the Pipeline Safety Trust’s Monthly Incident Dashboard

- Read a broad overview of arguments for and against carbon pipelines from the Institute for Carbon Removal Law & Policy here

[MUSIC: Fred Simon, Bonnie Herman, and Liz Cifani, “Time and the River” on Soul of the Machine: The Windham Sampler of New Electronic Music, by Fred Simon, Windham Hill Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Hydropower equipment in Muttersholtz. The town’s municipal buildings are all powered by clean energy, with plans to include residential homes soon. (Photo: Laurent Jerry. Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

DOERING: It's time now for look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter is a Living on Earth contributor and he joins us from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey, Peter, what you got for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Jenni. Start out with a little good news, or at least some potentially inspirational news for communities around the world. There's a small village in the northeast part of France called Muttersholtz. It's right along the German border near Belgium, in the area where a lot of the big battles for World War One and World War Two were fought. Now they're battling on behalf of clean energy. And that little town has all of its municipal electric power paid for because they've invested in conservation and in solar and in turbines put in the local river in order to generate water power. Those three things are saving their taxpayers a lot. The town even makes some money back when they sell their excess electricity back to the grid. Individual homeowners and those taxpayers still have to pay for their own electricity. But it's a big step forward not having to pay for streetlights and everything that might power a community.

DOERING: Wow. Well, this comes at just the right time, Peter, because as you know, Europe is facing sky high energy bills.

DYKSTRA: That's right, and largely because of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and all of the pressure that's been put on Europe to move away from buying fossil fuels from Russia. They've made the conversion. It's cost everyone some money, except for this one little town.

DOERING: Indeed. Well, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: There's a story about narwhals in the Arctic; narwhals are those really cool creatures that look like something out of the cartoons or out of Dr. Seuss or out of a B–52's song. The males have a spiraling tusk that extends for a long way out of their snouts. But narwhals may have trouble in the future in a warming Arctic Ocean in finding enough food to continue to thrive. There's concern, as expressed in a recent paper in the journal Biology Letters, that narwhals may be too reliant on winter feeding to have good prospects for survival.

A pod of narwhals. A recent study suggests that narwhals may be overly dependent on winter hunting, which may be negatively impacted by melting arctic ice. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

DOERING: How are narwhals doing as a species? I mean, we sometimes hear too late about species that are on the brink of extinction. But how are they doing?

DYKSTRA: They're not considered endangered, but there's a real concern that we may be pushing them in that direction.

DOERING: Hey, Peter, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

DYKSTRA: Last week, I talked with Bobby Bascomb about a 1799 United States law, the Federal Timber Purchases Act, probably the first US conservation-oriented law. Nearly 100 years later, to the day, March 3rd, 1899, Congress passed the Rivers and Harbors act, later signed by President William McKinley. And there's a big section of this law called the Refuse Act that offered criminal penalties for dumping in the waterways and also rewards for anyone who turned in dumpers. That part of the law, the Refuse Act, went mostly neglected until the 1960s, when some of the lawyers and activists working to clean up the Hudson River used that old and neglected law to help clean up the Hudson. Environmentalists and advocates found another tool for their toolbox to help clean things up. And that law has been a key to building more and more protection for American waterways, culminating of course, in the Clean Water Act passed in the 70s and strengthened since then.

DOERING: Well, we can thank the Congress of 1899 for giving us our first clean water law in the US. Thank you so much, Peter. Peter Dykstra is a Living on Earth Contributor. We'll talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: All right, Jenni. Thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you soon.

DOERING: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- This French village enjoys ‘no bills’ after building wind turbines and solar panels

- Read the narwhal study here

- Learn more about how blue-collar fishermen used the Clean Water Act to clean up the Hudson River

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Sound Escapes – Learning to Be a Deep Listener

A gilded barbet perches on a tree branch. (Photo: © Dusan M Brinkhuizen)

BASCOMB: Industrial and other human-made noises permeate our modern world. But nature is still singing, if we just listen. BirdNote®'s Ashley Ahearn has more.

BirdNote®

Sound Escapes - Learning to Be a Deep Listener

AHEARN: Gordon Hempton is a sound recordist who has spent his life capturing the sounds of the natural world. He’s learned to be a deep listener, kind of like a sonic meditator. And after a lifetime of traveling the world and listening and recording, he still is amazed by what he hears.

HEMPTON: I was recently in a very remote part of the Amazon rainforest. And I just was taking it all in. And I begin to hear the insect patterns, and how they are rhythmic and each rhythm is a different insect, especially as the light weakens and we make the transition from day into evening and night. Oh my God. And I realized this is the sound of the spinning Earth. That this is actually like a huge clock -- it’s just so elaborate and so precise that is beyond human invention.

Gilded barbets are found throughout the western Amazon Basin. (Photo: © Dusan M Brinkhuizen)

[Zambo Ambi]

Now Gordon wants to help you learn how to start listening to the workings of that massive natural clock. You can get started at birdnote dot org slash sound escapes. ###

Written by Mark Bramhill

Bird and nature recordings by Gordon Hempton.

BirdNote’s theme music composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler; Managing Producer: Jason Saul; Editor: Ashley Ahearn; Associate Producer: Ellen Blackstone; Assistant Producer: Mark Bramhill. © 2019 Tune In to Nature.org March 2019/2022 Narrator: Ashley Ahearn ID# hemptong-SE-Amazon-01-2019-03-07 hemptong-SE-Amazon-01

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/sound-escapes-learning-be-deep-listener

BASCOMB: For pictures, head on over to the Living on Earth website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Find this story on the BirdNote® Website

[MUSIC: Michael Oakland, “Samba De Gaia” on Witness Tree, by Michael Oakland, TTM/Outermost]

DOERING: Coming up – How the changing climate is altering what physical traits are an advantage in nature. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michael Oakland, “Samba De Gaia” on Witness Tree, by Michael Oakland, TTM/Outermost]

Cliff Hanger

A cormorant in the Falklands builds a cliff-side nest with his mate. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

LENDER: Cormorants are a relatively large aquatic bird well known for their diving skills. Some species are so good at hunting fish this way that some artisanal fishermen Asia have been known to tame the birds and use them to retrieve fish. But in the United States cormorants are seen as competition for aquaculture so the government has a program to cull a number of them each year. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, recently visited the Falkland Islands and got a chance to see cormorants at their best.

LENDER: On the eastern edge of the Falklands, above Land Mine Beach, nearing the limit of the cormorant’s southern reach one flies straight into the cliff! And in the last instant by some vertical magical lift, drops his tail and hovers for a heart, beat. Then plants himself on the narrowest slice of hard granite ledge. Cormorant arrives with gifts. Seaweed, crimson-purple, shaped like tiny pincers all clinging to itself. And the color a complement to the glow of citrine-eyes, and the tangerine-colored faces of him and his mate.

His gift she graciously takes, beak to beak.

Then nodding and leaning and weaving together they restate their deep and mutual vows. Confirming, all that will follow now and the rightness of it. How it should, and must be. And he spreads his wings (the iridescence in the nightblack of his feathers like electricity, the white of his breast a patch of fresh, blown, snow) and steps, out, into empty space.

The Antarctic Shag, or Blue-eyed Shag, is a species of cormorant that lives off the icy Antarctic Peninsula. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And drops …

Away…

Once again to work the cold sea.

Black-crowned night herons, their heads adorned with a quill pointed as a hatpin, go about their business and ignore me. Rock hopper penguins, yellow hair flopping come rock-hopping up and up the steep stepstone slope like all their generations before, and before. An oystercatcher cleaving to her nest behind the dunes will not move for anything, or anyone. Defiant. Though, she need not fear.

It is only the cormorant that is truly despised.

On every coast of the Americas; West, and down around Cape Horn; along the length of the Eastern Seaboard here and there and there, cormorants of many kinds shape the sea to their intentions. On the remnant of a volcanic cone off the Antarctic Peninsula, with eyes as blue as glacier ice; under the clear waters of Crystal Spring, rainbows of bubbles chasing behind them; in the turbid saltwater wash of New England where they perch on pilings and spread their pterodactyl wings toward the sun like clothes pinned to the line… I wonder, do they know, the full extent?

To which they are hated.

For the best things about them:

That they fly through water the way they swim through air all of them thinking all the sea belongs to them, and all the little fishes they will find!

When we know the ocean and all things in it, and every turn of the tide belongs only, to us.

DOERING: Mark Seth Lender is Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence.

Related links:

- Read Mark's Field Note for this essay

- Mark Seth Lender | “Mark Seth Lender’s Photography and Writings"

[MUSIC: Aine Minogue, “King of the Faeries (Ri na Sidhoga)” on Were You At the Rock, traditional Irish, Beacon Records]

Climate Change and Mating

A common whitetail dragonfly. Evolutionary ecologist Michael Moore began investigating the link between climate change and mating when he learned dragonfly species that typically have dark wing pigmentation have less or no pigmentation in hotter parts of their species range. (Photo: TexasEagle, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Most animals select a mate based on a phenotype, or observable trait. Think of a bird’s brightly colored feathers or a male lion’s mane. Certain traits are associated with better genes, so individuals will select a mate based on the quality of their display, which drives evolution of the species. But, climate change is making some classically attractive traits more difficult to pull off. For more I’m joined by Michael Moore, an assistant professor of Biology at the University of Colorado Denver. Michael Moore, welcome to Living on Earth.

MOORE: Thanks for having me.

BASCOMB: So this may be a bit of an obvious question, but can you give us a brief overview, please, of what is sexual selection exactly?

MOORE: Yeah, so sexual selection is a type of natural selection. But instead of the differences in individuals being the result of survival, it's differences in individuals being the result of reproduction. And so we often think about sexual selection as kind of the advantages that some individuals get from having these really big, showy traits. But really, it's about kind of any sort of traits that just sort of improves an individual's ability to coordinate mating and successfully mate with a partner.

BASCOMB: So is it about mating or successful offspring?

MOORE: It's often really hard to distinguish between those things. Usually, for practical reasons, we usually focus on the point at which two individuals mate with one another, but obviously, that mating doesn't do any good if they don't successfully have the offspring.

BASCOMB: And so what first got you interested in this question of how climate change is affecting sexual selection?

Example of dragonfly wing pigmentation. Although darker wings might attract more mates, they can cause the males who have them to overheat. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Moore)

MOORE: Well, it started actually, with an observation that this dragonfly that I was working on for other research reasons, I was working on this trait that these dragonflies have that helps them in sexual selection. It's this dark pigmentation on their wings that males use to attract females and to scare off territorial rivals. And what was really interesting about this trait was that where I was working in Cleveland, the species that I was working on had this really big dark patch on its wing, but we knew in western portions of the species range, and in the southern portions of the species range, the dragonfly just didn't have any of this pigmentation whatsoever. And that was kind of an anecdote that I was aware of, but had kind of filed away for a rainy day. And then one sort of winter when I was unable to do the field research that I would normally do during my PhD because the dragonflies are all sleeping during that time, I started to think about what it might mean that these dragonflies don't seem to have this wind coloration in the hottest parts of the species range. And so what we found is that, you know, even though these dragonflies have this really important mating trait, because it's this dark pigmentation, it absorbs a bunch of solar radiation, and it leads to these dragonflies actually overheating in the warmest parts of the species range. And so we started by thinking about this question just in terms of long evolutionary histories, right, the kinds that were involved, as the species colonized all of North America. But then obviously, the immediate implication of that is, if dragonflies are having a hard time having this really important meeting trait in warm parts of the species range, will they also have a hard time having this really important mating trait as our climate continues to warm? And what my research indicates is that it appears that even just over the last fifteen years, we're starting to see really big shifts in how much wing pigmentation and how large these mating traits are for these dragonflies, as our climate continues to warm.

BASCOMB: I'm just wondering, in terms of these darker pigmented dragonflies, are you able to actually take their temperature or in some way learn that there may be overheating when they're darker and absorbing more of the solar radiation?

MOORE: Yeah, so we did an experiment where we captured dragonflies with different amounts of pigmentation on their wings, and we brought them into the lab and we heated them up under a lamp as if they were like out in the sun sort of collecting that solar radiation. What we found for this first study just by looking at individuals with natural differences in how big their pigmentation is, is that the individuals with more pigmented wings tend to heat up faster and to a higher overall temperature than the ones that have less of that pigmentation on their wings. The thing that was tricky about that, though, is that it's natural differences between individuals. And so it could be because of the wing coloration or it could be because of some other factor that's associated with the wing coloration. So what we did is we captured another set of dragonflies that all had very little wing pigmentation and then we manually added the pigmentation with a brown felt tip marker. And then as sort of a control in this experiment, we colored in the same region of the wing with colorless blending ink, which has all of the same sort of chemical properties as a felt tip marker, but lacks any of the dye. So that controls for any kind of effect of just putting the marker on the wing. And so we did the second experiment with these individuals where we augmented the wing coloration and individuals that had this control marker ink on the wing. And what we find is exactly the same pattern. So that gives us really strong experimental evidence that the wing coloration actually does seem to be associated with heating up.

A pair of blue dashers mating. Researchers have yet to learn how changes in male wing coloration are affecting the way certain species mate. (Photo: reophax, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: So it is indeed the darker wings on the dragonfly that causes it to be warmer, not just some trait that dark winged dragonflies happen to have.

MOORE: Yeah, that's what it seems like.

BASCOMB: So if male dragonflies are becoming less dark as a way to stay cool, that must mean then that the less dark males survive better and were better able to reproduce, you know, more fit offspring.

MOORE: There's a few possibilities here. It could be that the females simply choose to mate with males that have less wing coloration, just like you said, and in that case, there wouldn't be necessarily any conflict over any of this. The females would choose the males that are going to have the wing coloration that they would like their offspring to have, because it'll be really well matched to the temperatures that their offspring are likely to face. The other possibility is that the females don't realize that they need to mate with males with less wing coloration, they either mate with males that have more wing coloration than is optimal for the climate, or, if they can't find those males, because all of those males have died or they're simply too warm to go to the breeding aggregations, then the females might not mate at all. And that's going to have really big implications for kind of the long term success of some of these populations. If females are essentially so choosy, and they can't find the mates that they have historically mated with because those males are dead, then we could see sort of really big declines in population because there's not successful reproduction occurring. So we don't know which of those possibilities is occurring yet. It's one of the things that my lab is starting to look at. But I don't have any clear answers for you at the moment.

BASCOMB: I know you've been looking at dragonflies, but what other animals out there are exhibiting changes in their mating behavior that you are attributing to climate change, potentially?

A lion rests in the grassland of Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. The big, dark manes that traditionally boost lions’ mating appeal may be hindering them more than helping them. (Photo: Diana Robinson, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MOORE: So we're still really in the early stages of a lot of it. But there's a lot of research going on. I think one of the real famous examples besides some of the dragonfly work that I've been doing is what we see in lions. And so lions that have really big dark manes also tend to overheat even though those big dark manes are beneficial to the male lions. So across these lions' geographic ranges in Africa, what we tend to find is that the lions in the hotter parts of Africa tend to have less dark manes or smaller manes. There's some interesting research in birds where some of their breeding plumage is starting to change as a result of it being too warm. Most of the research that we've looked at so far has really been about these kind of color based traits. But we're also starting to learn about other types of traits that might be affected that aren't necessarily as intuitive. So one of my collaborators at St. Louis University, Kasey Fowler–Finn, her research looks at how these little tree hoppers, which are these little insects, how they're able to sing under different climatic scenarios. And so what she's finding is that their songs are totally different at warm temperatures than they are at cool temperatures. And this has to do with their kind of energetics and some of the physics associated with how they sort of produce those vibrational songs that they use to communicate with one another.

BASCOMB: And those songs are used to attract a mate?

MOORE: Yep, in addition to attract mates, it's also to sort of tell another individual what species you are, and that has all kinds of implications for these things that we're talking about, about whether individuals of the same species can recognize one another, whether females can successfully choose the right male or not, all of these different things.

BASCOMB: Well, you know, climate change can mean a lot of things. It can be wetter or drier, you can have more storms, more extreme weather events, and of course, it's hotter. Are there other factors other than heat that are impacting the way that animals mate and choose their mates?

MOORE: Yeah, so one of my collaborators Noah Leith, who is also at St. Louis University, right now he's looking at how aridity is affecting some of these mating traits. And so he works on wolf spiders and so what's really interesting about spiders is that the way that they move their limbs is based on hydraulics. So they move fluid around in their body to sort of move their limbs and such. And so what he's looking at is, as the planet gets drier as a component of climate change, how are those drier conditions going to affect the mating behaviors of these spiders? And I think a lot of his research is still ongoing. We're not certain how the results are coming out. But we're definitely starting to think about some of the other impacts of climate change on some of these mating behaviors.

A pair of treehoppers. Researchers at the Fowler-Finn lab are looking into the ways warming temperatures are affecting treehoppers’ mating songs. (Photo: patrickkavanagh, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, of course, you know, the Earth is not stagnant, and the climate has always been changing. But with anthropogenic climate change, it's the speed of change that's so concerning. How possible is it do you think for species to evolve enough to avoid this pattern that we've been talking about here, to be able to attract suitable mates when the game has changed for what suitable means anymore?

MOORE: So we know that in general, that many organisms do have the capacity to adapt to the rapidly rising global temperatures. But what we're seeing is that a lot of animals, even though they are showing some adaptation, it doesn't seem to be fast enough. And so a big question in biology right now is, is why aren't they adapting fast enough given that they, from what we understand about them, they do seem to have the resources to be able to facilitate kind of a genetic adaptation? And they do seem to show some response. It's just not big enough. So we don't know the answer to that yet. Increasingly, we're realizing that adaptation is one of the components that animals are going to have to use in order to respond to climate change. And so really getting to the bottom of this question I think is particularly urgent.

BASCOMB: Now from what I understand your study on dragonflies and their wing patterns use data generated by iNaturalist. Can you tell us a bit more about that and how people can get involved with this?

A wolf spider with spiderlings on her back. Noah Leith at St. Louis University is investigating how aridity affects wolf spider mating. (Photo: imarsman, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND-2.0)

MOORE: So iNaturalist is this is really terrific, what we call citizen science platform. And so people can take observations of any kind of plant or animal or other organism they see just with their smartphone and upload it via this app to this website. But what is really exciting about the iNaturalist program to a researcher like me is that every time that someone takes one of those pictures and uploads it to the website, we have a record of an organism that was observed. We know when it was observed, we know where it was observed, and we have an image that we can use to study the traits of the animal. And so this has allowed us to do really cool things, to look at sort of geographic patterns and animal traits across North America. So that's actually how my dragonfly research was conducted. But we can also look at how animal traits are changing through time because we have that timestamp associated with each individual observation of the dragonflies. But there are other people who are really excited about getting citizen scientists involved and have specific projects on iNaturalist, and I encourage your listeners to go and check out some of those projects that are available and get involved as much as possible because the way that science is gonna have to move forward in the future is not just with or professional scientists like me, in the lab or in the field, but the scale at which we need to start to observe how organisms are responding to things like climate change is so large, that we're really going to need to involve every person to the extent that they're capable or interested.

BASCOMB: Michael Moore is an assistant professor of biology at the University of Colorado Denver. Michael, thank you so much for your time today.

MOORE: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Washington Post | “Less Attractive, Less Picky: How Mating Is Changing in A Hotter World”

- Science News | “Climate Change May Rob Male Dragonfly Wings of Their Dark Spots”

- Michael Moore on Twitter

- Sign up for iNaturalist here

- Click here to learn more about how climate change is affecting treehoppers’ songs

[MUSIC: Philip Boulding, “Margaret’s Arrival” on Musings: Celtic Harp Originals, by Philip Boulding, Magic Hill Music]

DOERING: Next week on the show a plan to place a value on nature and ecosystem services.

BLIMES: So we all love whales. But how much is a whale worth in terms of what it contributes to the economy? Well, in fact, one whale is worth at least $2 million, because the big whales such as sperm whales and filter feeding baleen whales help sequester carbon by hoarding it in their bodies. And they stockpile tons of it, like swimming trees. And if you put it into quantitative terms, a mature tree absorbs up to 22kg of carbon each year, but a single whale in its lifespan stores about 33 tons of carbon dioxide, which means that one whale does the job of 1,500 trees.

DOERING: Valuing nature to encourage conservation, that’s next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Philip Boulding, “Margaret’s Arrival” on Musings: Celtic Harp Originals, by Philip Boulding, Magic Hill Music]

DOERING: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Fern Alling, Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Swayam Gagneja, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Jusneel Mahal, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, El Wilson, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. And you can write to us at comments at loe dot org. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth