June 6, 2014

Air Date: June 6, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

EPA To Regulate Emissions From Power Plants

View the page for this story

US EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy has proposed new rules to reduce global warming emissions from existing power plants. Host Steve Curwood lays out the new rules that would cut emissions 30% by the year 2030, and some of the objections. (03:00)

A Regional Model for Reducing Power Plant Emissions

View the page for this story

Some critics argue that EPA’s proposed rules to reduce global warming emissions from power plants will prove costly. But as Environment Northeast’s Peter Shattuck tells us, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, a cap and trade program in Northeastern states shows that carbon regulation can cut power plant emissions and raise money at the same time. (08:50)

International Response To Proposed EPA Regs

View the page for this story

The US is the world's second largest emitter of global warming gases and has been under pressure from the international community for not signing on to binding emissions cuts. Jennifer Morgan from the World Resources Institute tells host Steve Curwood that there's a positive reaction to the EPA’s new plan, and it may help spur a new global climate treaty. (06:30)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about flounder in a new place and a possible environmental cause for some health problems of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. (04:10)

Iron-eating Bacteria

/ Ari Daniel ShapiroView the page for this story

Ari Daniel travels into the field with microbiologists to report on some very strange bacteria that consume iron and may help filter water in the future. (05:40)

Gold-Mining in Alaska

View the page for this story

Five gold-mining projects have been proposed on the British Columbia and Alaska watershed, threatening important salmon populations and pristine rivers. Chris Zimmer, the Alaska Campaign Director for Rivers without Borders, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss the environmental dangers of the proposed mines and the response of the two governments. (06:00)

John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire

View the page for this story

Author Kim Heacox argues that John muir might never have become an environmentalist had he not visited Alaska, and discusses his new biography "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire" with host Steve Curwood. (08:00)

Whooper Swans of Southern Iceland

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Writer Mark Seth Lender watches as a group of Whooper Swans in a southern Icelandic pond reluctantly take to the air as a snowstorm closes in. (03:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Peter Shattuck, Jennifer Morgan, Chris Zimmer, Kim Heacox,

REPORTER: Peter Dykstra, Ari Daniel, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: The EPA's Gina McCarthy says the agency's new plan to cut CO2 emissions from power plants is a win for health, the environment and the pocketbook.

MCCARTHY: Can we cut pollution while keeping our energy affordable and reliable? Sure we can! We can and we will! Critics claim that your energy bills will sky-rocket. Well, they're wrong! Shall I say that again? They're wrong!

[APPLAUSE, LAUGHTER]

CURWOOD: But there are still plenty of critics...

SHATTUCK: There are some who say it doesn't go far enough, some who say it goes too far, I think when this process is finally resolved we're going to see 50 states having to do something about their CO2 pollution. So it's an important first step in that direction.

CURWOOD: We'll have that, an odd ecosystem in a ditch, and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

EPA To Regulate Emissions From Power Plants

The new EPA regulations set a goal of a 30% reduction in carbon dioxide emissions by the year 2030. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. By the year 2030, the US will cut global warming gas emissions from existing power plants by 30 percent. That's the effect of the proposed Clean Power Plan that EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy announced on June 2. Taking action to combat climate change is imperative, she told the press.

MCCARTHY: For the sake of our families’ health and our kids’ future, we have a moral obligation to act on climate.

CURWOOD: It's not only a matter of morals, she explained, it's a matter of smart money to push back against the climate disruption we're already seeing.

MCCARTHY: 2012 was the second most expensive year in U.S. history for natural disasters. Even the largest sectors of our economy buckle under the pressures of a changing climate, and when they give way, so do businesses that support them, and local economics that depend on them.

Gina McCarthy is administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. (Wikipedia)

CURWOOD: Under the proposed new rules, states will have incentives to choose clean power solutions and energy-saving technologies - and that will bring some benefits.

MCCARTHY: In 2030, the Clean Power Plan will deliver climate and health benefits of up to $90 billion dollars. And for soot and smog reductions alone, that means for every dollar we invest in the plan, families will see $7 dollars in direct health benefits. And if states are smart about taking advantage of efficiency opportunities, and I know they are, when the effects of this plan are in place in 2030, average electricity bills will be eight percent cheaper.

CURWOOD: But the coal industry, some lawmakers and business interests have a different calculation.

ZYCHER: There's a recent Chamber of Commerce study that says the costs will be above $50 billion a year and I'm prepared easily to believe that. It's hard to believe it would be much less.

Ben Zycher is the John G. Searle Chair for the American Enterprise Institute. (American Enterprise Institute)

CURWOOD: Benjamin Zycher is a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, and he argues not only may these rules lead to electricity blackouts and destroy jobs, they're based on partisan politics.

ZYCHER: The effect will be to raise the cost of energy in states that are disproportionately dependent on coal-fired power. Those are basically red states in the south, southwest, and mountain areas. The real purpose of this is to increase the competitiveness of blue states in terms of their energy costs relative to red states. That's really the underlying politics of all this.

CURWOOD: And Zycher says the rules won’t even do much to help rein in global warming.

ZYCHER: The policy will have no effect at all on climate change regardless of what you believe about the underlying science. The proposed rule, even if it were implemented immediately, would reduce temperatures in the year 2100 by about 0.02 of a degree which is essentially not measurable.

CURWOOD: That's Benjamin Zycher of the American Enterprise Institute.

Related links:

- EPA Clean Power Plan

- Gina McCarthy Blog on the Clean Power Plan

- American Enterprise Institute

A Regional Model for Reducing Power Plant Emissions

The new regulations crack down on CO2 emissions from power plants (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Well, despite a 2007 US Supreme Court decision that requires the government to regulate CO2 as a pollutant, legal challenges to the EPA power plant rules are expected. The precedents to the Clean Power Plan include a cap and trade program to reduce sulfur and nitrogen pollution from power plants that began back in 1990. And today California has a cap and trade program to cut global warming gases, and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, is a five year old collaborative effort among nine northeastern states related to their power sector. RGGI has just published a report detailing progress to date, and the lead author Peter Shattuck, director of market initiatives with Environment Northeast, came into our studio to talk about it and the new EPA rules. Welcome to the program.

SHATTUCK: Thanks, glad to be here.

The coal industry has complained that the new rules disproportionately target coal (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: What’s your reaction to this proposed regulation?

SHATTUCK: The proposal is important because it starts a process that really grounds the climate debate in a substantive discussion about what we can do and what is being done to reduce greenhouse gas emissions already. So there are some say it doesn't go far enough, some say it goes too far. I think when this process is finally resolved, we’re going to see 50 states having to do something about their CO2 pollution so it's important for a step in that direction.

CURWOOD: Now, this rules proposal from EPA is not a one-size-fits-all. EPA is instead giving states the power to figure out a way to get to these targets on their own. Can you explain that to us?

Hurricane Sandy in 2011 brought home the impact of climate change in the United States (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

SHATTUCK: It's an important element of this proposal...is the decision to base the targets on where states are right now and what they're capable of in the future, and this proposal effectively says use what you have now but insure that you are reducing emissions from a diversity of potential approaches from building cleaner sources of generation into investing in energy efficiency to just using the cleaner sources of power that we have with greater frequency.

CURWOOD: Now, what you think of this state-by-state approach? How fair is it to say that maybe EPA's letting industry off a bit easy here?

Steve Curwood with Peter Shattuck (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

SHATTUCK: That would be one of the criticisms, that if you had a uniform standard you would probably get the dirtier states to clean up more quickly from a CO2 perspective. The challenge is, states are starting from different places. If you look through the lens of what we've seen here in the northeast, we’ve made a lot of investments in cleaner power and cleaning up existing power plants, but that leaves us with a fundamentally different starting point. So there's inherently a political trade-off. If you try to hold Midwestern states that are much more dependent on coal to a similar standard, the economic impacts would be a lot greater, so I think there's inherently some politics at play, but that is the essence of policymaking.

CURWOOD: There’s criticism from the environmental advocacy side who say that look, a 30 percent reduction based on the level of CO2 in the atmosphere in 2005 doesn't really make a lot of sense since there have been a fair amount of reductions since then. What's your opinion?

SHATTUCK: I think the level of stringency, the level of ambition is clearly important, but more important is to get the process started. So we have an interesting case study here in the Northeast with the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative where emissions have dropped by almost half since states, including Massachusetts, launched the program only five years ago. And what that led to was a decision by participating states to increase the level of ambition, and we could well see something similar once a starting point is established, if we end up making faster progress, or need to act more quickly, we can do that down the road.

Peter Shattuck (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: So you’ve been involved in the implementation of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative here in the Northeast. How well would you say that this multistate approach is working?

SHATTUCK: I think it's worked very well to show that a market-based program, a cap-and-trade program - dirty word that it is - can be effective. It has led to this significant drop in emissions that we’ve seen in the last five years and amazingly we've actually seen electricity prices drop at the same time.

CURWOOD: Wait a second, Peter, you’re saying in the Northeast CO2 emissions have gone down by what, some 40 odd percent, and the price electricity has gone down?

SHATTUCK: That's right, so it's very helpful in rebutting some of the criticism of this proposed regulation that it will necessarily cause electricity prices to increase. In fact, even the RGGI states before they launched this program projected a modest increase in prices. Instead we’ve seen a decline and I think that's an important reflection of the fact that a market-based program is intended to drive innovation, yet we can only predict at any one point in time what we know. If we could predict innovation it wouldn't be innovation, so what you have by setting a price on pollution you create incentives for people to innovate, that tends to happen, and you get lower cost than anticipated.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think of the RGGI program, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, will serve as a model for other states to follow as they try to meet the requirements of the proposed EPA rules?

SHATTUCK: I think RGGI's going to get a lot of attention as an effective means of meeting these new requirements from the EPA. An article by Coral Davenport at the New York Times had two of the largest coal generators in the country stating their preference for flexible market-based programs like RGGI, and when you have companies like AEP and First Energy saying, “You know what? This makes sense. Cap-and-trade is the most cost-effective way of reducing emissions, it creates the most flexibility to basically get deeper reductions for less money”, I think people start to take a second look at programs like RGGI, and on top of that some of the funds that the RGGI states have raised through the program -- approaching $2 billion now -- to reinvest in energy efficiency, clean energy in the region, I think that's appealing to other states, the idea of maintaining control over the value of the new currency of these cap-and-trade programs, so maintaining control through the purse strings, I think, is something that fundamentally supports the appeal of RGGI beyond the region.

CURWOOD: Where does the money come from for the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, the RGGI program?

SHATTUCK: The way RGGI works is that power plants have to buy a permit for each ton of CO2 that they dispose of in the atmosphere. These are called allowances, they are sold off in quarterly auctions where power plants bid for the right to pollute. The revenue that's raised is sent back to states to reinvest in energy efficiency and clean energy programs. The quantity of those permits decreases over time, and that is the cap declining, that's what sends the market signal to power plant owners and others to invest in cleaner alternatives and reduces CO2 pollution over time.

CURWOOD: So how much money has this process raised?

SHATTUCK: To date it has raised in the neighborhood of $1.8 billion.

CURWOOD: And what's the price for a ton of carbon right now under this plan?

SHATTUCK: In the last auction it was $4 a ton.

CURWOOD: So that's pretty cheap.

SHATTUCK: That is pretty cheap and folks often say how does that compare to say California where they have their own cap-and-trade program. Prices are about three times as high. And the important thing to remember is we’re not measuring the success of RGGI in terms of how high the carbon price is. We should be measuring success of these programs in terms of how far carbon dioxide emissions have declined, and to that extent, if it ends up being cheaper, lower cost, to reduce CO2 pollution than we anticipated, that's a good thing. So to have low allowance prices as long as the program’s working, as long as it's generating emissions reductions, is not a bad thing.

CURWOOD: What's the legal viability of this proposed rule on existing power plants? Industry says that they're going to challenge it tooth and nail, How successful do you think they will be based on the research you've done?

SHATTUCK: I think they've got an uphill challenge, especially with the recent decision by the Supreme Court around the cross state air pollution rule and this was a rule to use market-based programs, use cap-and-trade programs, to reduce other sorts of pollution from power plants that was challenged in the courts. The Supreme Court said, “You need to give deference to the EPA, they know what they're doing, they're the experts, let them have their go”, and I think the same should apply to this rule here.

CURWOOD: Peter Shattuck is the Director of Market Initiatives for Environment Northeast. Thanks so much for coming by, Peter.

SHATTUCK: Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Read Environment Northeast’s report on RGGI

- Environment Northeast

[MUSIC: Curtis Mayfield “Give Me Your Love” from Get Ready: The Curtis Mayfield Story (Rhino records 1996) Happy Birthday Curtis Mayfield]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how the proposed EPA rules affect America’s standing in the world of international climate diplomacy. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Devo “Gut Feeling/Slap Your Mammy” from Are We Not Men ? A: We Are Devo (Warner Bros 1978)]

International Response To Proposed EPA Regs

To cut emissions 30% by 2030 the US will have to scale back on traditional coal fired power plants. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Climate change is a global problem that requires a global solution, and the UN has been actively seeking one since 1992. But the United States, the world’s second largest emitter of carbon dioxide, has been unwilling to accept binding limits, even though other nations, including those in the EU, do. Still, as scientific reports about climate disruption have become increasingly urgent, so has the pace of negotiations towards a global treaty. Delegates are now meeting in Bonn, Germany, in the run-up to the 20th Climate Change Conference in Paris in 2015. So we called up Jennifer Morgan, the Director of Climate and Energy Programs at the World Resources Institute, to get a sense of how the proposed EPA rules are being received. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Jennifer.

MORGAN: Thank you. Great to be here.

CURWOOD: So I gather there’s a bit more optimistic mood at these interim negotiations there in Bonn.

MORGAN: Yes, there sure is. The recent announcement by the Obama administration that they're going to reduce emissions from their power sector is really making people more hopeful, I think, of an agreement next year.

CURWOOD: But how big of a deal are these proposed EPA regulations in terms of making a dent in the carbon emissions crisis?

MORGAN: They’re a very big deal. The power sector is the largest polluting sector of greenhouse gases in the United States making about 40 percent of our emissions, and these standards will tackle those emissions and drive them down step-by-step and bring in renewable energy and energy efficiency and natural gas and make a big dent to meet international commitments.

CURWOOD: These interim negotiations are just beginning there in Bonn. What's the European response to these proposed rules?

MORGAN: Well, there's been a formal response from Europe that this is the most ambitious and the biggest steps that they've ever seen from a US president, very much welcoming it. And I think on an informal level, I think, in some ways it creates a sense of competition now between Europe and US because you now have a US administration that's really acting to reduce emissions in the sector which in some countries in Europe is actually growing, so it's a bit of a ‘game on’ competition spirit as well.

CURWOOD: Jennifer, compare for me the EU goals reducing greenhouse gas emissions to what president Obama has put on the table.

Jennifer Morgan is Director of Climate and Energy Programs at the World Resources Institute. (Photo: World Resources Institute)

MORGAN: Well, the EU has a target of reducing its emissions 20 percent below 1990 levels by 2020 which actually it's very much on track to meet. The US has a goal, which is reducing emissions of 17 percent below 2005 levels which is kind of comparing apples and oranges. It's a smaller reduction below these 1990 levels, so if you look at historically you can see the EU’s really taking a leadership role, they've been putting in policies and measures for decades now to reduce their emissions, and the US with the Obama climate action plan is really just stepping up into this space and showing that they're serious about tackling the problem.

CURWOOD: Now, what about China? China all along has been saying that the US needs to get its act together. How are the Chinese responding to this?

MORGAN: Well, the Chinese, I think, informally, have been watching this space very closely and in fact one of the key advisors to the Chinese government came out the day after the US standards were put forward noting that China is considering an absolute cap on its emissions and a peak of those emissions and a downward trend after that. Now this isn't a formal Chinese government position but it's pretty clear that China it's watching the US and seeing whether or not it serious enough to reduce the US emissions before it actually says what it will do. Again it's open trust and confidence, I think, in the intent of the US to reduce emissions that is helping other countries step up to the plate.

CURWOOD: Given what the US has now put out on the table, what do you think the deal might look like eventually coming out of Paris the end of next year?

MORGAN: I think that with the US putting this proposal on the table for implementing its current commitments it will make it more likely that the agreement in Paris next year can be ambitious, and I say that because each country looking at each other to see are they serious about tackling this problem, have they met their existing commitments, what are they actually doing? With the Obama administration showing they are serious, they are reducing emissions from the sector, it brings, I think, hope and more credibility for other countries to come together around more ambitious targets moving forward in the Paris agreement next year.

CURWOOD: What do you say to critics who say that, you know, what Obama's proposing to the Europeans are doing simply not enough to address the climate crisis?

MORGAN: I agree with them. I think that what countries have put forward, including the Obama administration, right now is not enough. The problem of climate change is at our doorstep, the impacts are happening and the transition into renewables and energy efficiency needs to occur faster in the United States, faster in Europe, faster in China and my hope is that by working together and show each other that they're serious they'll take even bigger steps next year in Paris.

CURWOOD: You're in touch with various folks in the administration, I'm wondering if Obama sees that this is a huge legacy issue for him, that this is what he wants to wrap his presidency in towards the end of his time [in office]. What’s your perception?

MORGAN: My perception is that he really deeply understands the risks that climate change poses to Americans, to the United States and things that people care about, and that also that he has two children and we know that that generation will be having to deal with these issues if this generation doesn't. So I think that this is a legacy issue potentially for the president driven by science and driven frankly by a moral cause to avoid just disaster for his kids and other people's kids around the world.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Morgan is Director of Climate and Energy Programs at the World Resources Institute. Thanks for taking the time with us today.

MORGAN: Thanks very much for being in touch.

Related link:

World Resources Institute

[MUSIC: Dirty Dozen Brass band “Save The Children” from What’s Goin On (Shout Factory 2006)]

Beyond the Headlines

US solders are experiencing health impacts from metals they inhaled in Iraq (Pfc. Nikko-Angelo Matos, Dept. of Defense)

CURWOOD: We turn now to Peter Dykstra. He's publisher of Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org for a peek beyond the headlines. He's on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. I’ve got an epic tale from the sea that has everything.

.png)

Flounder may not be the prettiest fish, but they’re a popular choice for fisherman up and down the east coast (photo: Pearson Scott Foresman)

CURWOOD: Ah, Moby Dick, huh?

DYKSTRA: No, it’s more like “Gone With the Wind” but with flounder, also known as “fluke” to east coast fishermen. They have been through a lot in the last 30 years. The summer flounder population, and the catch for both commercial and sports fishermen dropped dramatically in the 1980s, and then it re-built following the imposition of catch limits that nobody liked.

CURWOOD: Well, except maybe the flounder…

DYKSTRA: Point taken. But these fish, considered to be both delicious and quite ugly, didn’t just bounce back in a big way after the catch limits came in, they bounced back in a completely different place. North Carolina is where most of the flounder boats have always been based, and these days, those North Carolina boats travel all the way to New Jersey. That’s where most of the fish are now. They catch the fish there. They’re entitled to them under an old quota system that was established when the flounder were flourishing off the Outer Banks, but the fishermen in New Jersey and New York are not happy with North Carolina boats working their waters, so it’s a saltwater Civil War in the making.

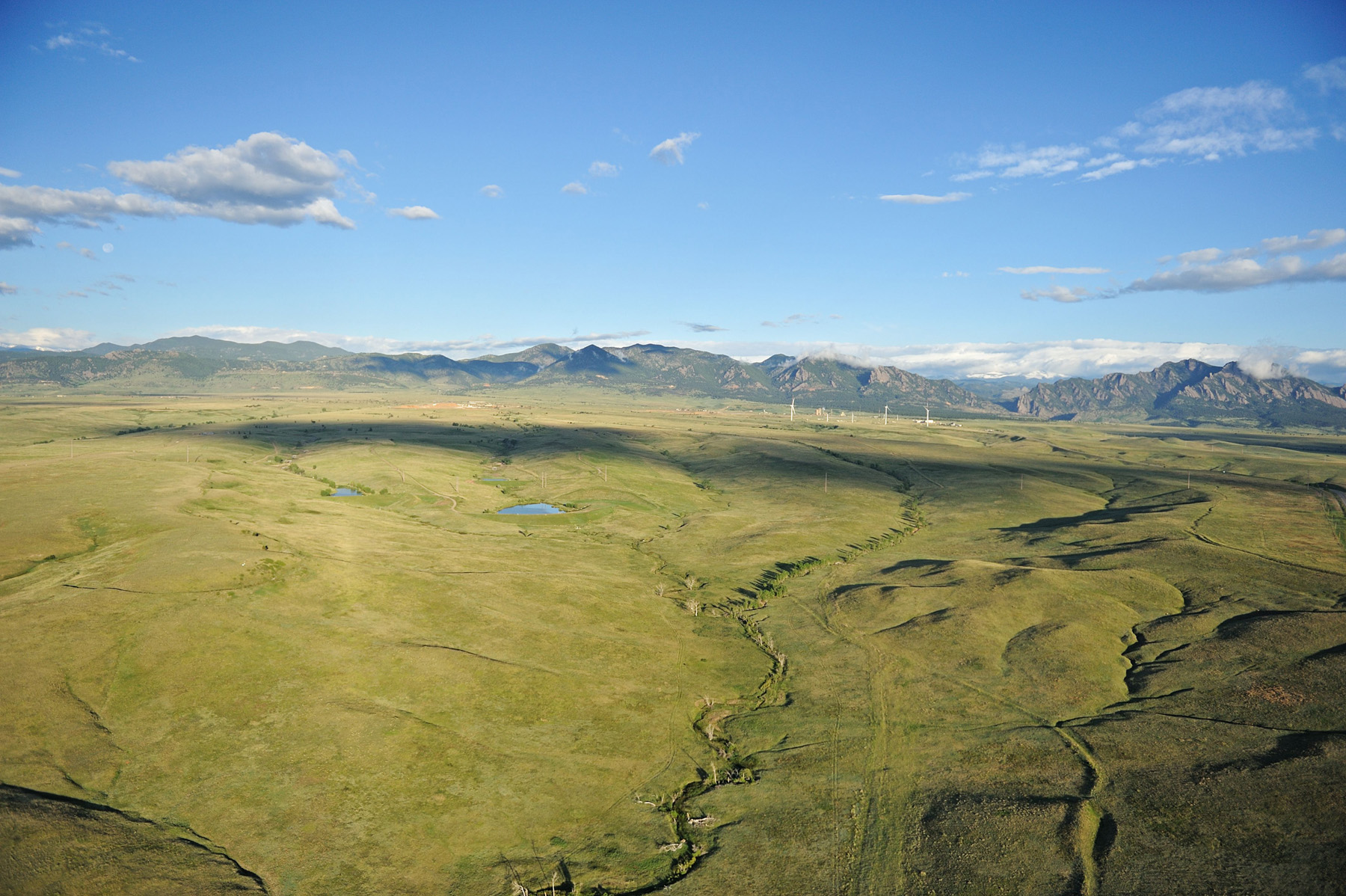

Once a nuclear weapons facility, Rocky Flats is now a wildlife refuge (photo: US Department of Energy)

CURWOOD: So this flip flop is perhaps due to climate change?

DYKSTRA: Possibly, but it’s not clear. There was a NOAA study recently suggesting that it’s not climate change, but other marine scientists say that there’s a link between warming waters and the fish stocks carpet-bagging their way up north. That story, by the way, is from our Daily Climate science reporter Marianne Lavelle.

CURWOOD: Ok. What’s the next item?

DYKSTRA: A good example of a tenacious reporter who “owns” a story: Kelly Kennedy has been following the health problems of veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars for years. She’s focused on burn pits, where military camps disposed of virtually every kind of waste in a big heap and set it on fire - from plastics to machinery to medicine to animal carcasses and sometimes even lost human limbs. Kelly has linked the indiscriminate burning to respiratory illnesses in veterans, but here’s a new one. Her story in USA today cites research linking veterans’ lung damage to “inhaled metals.”

CURWOOD: Breathing metals? How did that happen?

DYKSTRA: Possibly from the burn pits, possibly from exploding ordnance, possibly from other sources, but the veterans tested all had lung damage, and they all had microscopic shards of titanium in their lungs, and as you can imagine, tiny bits of metal can become major irritants for lungs. They’re not equipped to get rid of metal, just like lungs have trouble with coal dust, or cigarette tar, or asbestos fibers.

CURWOOD: As if veterans don’t have enough problems to deal with, health and other things. What’s your environmental history nugget for this week?

DYKSTRA: 25 years ago this week, the Federal government raided itself. About 70 agents from the FBI and the EPA showed up at the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons complex. It was run by the Energy Department. Rocky Flats is about a half-hour’s drive from downtown Denver.

And from the early days of the Cold War up until 1989 when the raid happened, Rocky Flats made the plutonium cores for nuclear weapons. In doing so, they also made an enormous mess. The raid temporarily shut the plant and subsequent investigations led to criminal convictions for Rockwell International, the contractor who ran Rocky Flats for the government. It also led to one of the biggest environmental cleanups in US history.

CURWOOD: And I’m getting the feeling this is not a story with either a happy ending or a quick one. What’s up with Rocky Flats today?

DYKSTRA: Rocky Flats closed for good in the early ’90s, the core site is fenced off, the Superfund cleanup is said to be complete, but some workers are still waiting for compensation for illnesses they say are related to their work with plutonium, with other radioactive substances, and with toxic chemicals.

And here’s one more thing -- the payroll office for the plant, located outside the contamination zone, is now a biker bar and sports bar called the Rocky Flats Lounge. The buffer zone around the site is about 4,000 acres, and it’s now a National Wildlife refuge.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is publisher of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org. Thanks, Peter, for taking the time with us today.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve, we’ll talk to you next week.

CURWOOD: ...and there's more on thes stories at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Summer flounder stir north-south climate change battle

- Environmental health risks for soldiers

- Feds raid Rocky Flats

[MUSIC: Marc Ribot “Todo El Mundo Es Kitsch” from Party Intellectuals (Pi Records 2009)]

Iron-eating Bacteria

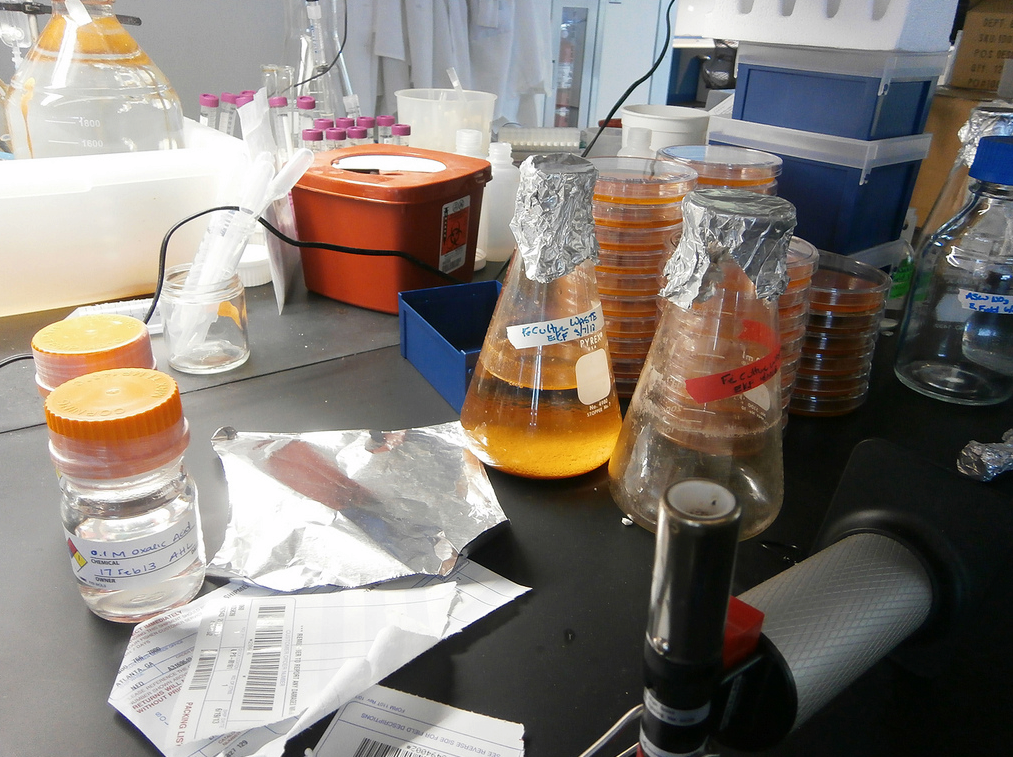

Bright Rust and Iron-oxidizing Bacteria (Ari Daniel Shapiro)

CURWOOD: In the quest to mend the ecological damage and imbalances humans perpetrate on the earth, many enterprising scientists are turning to the endlessly inventive natural world - for example bacteria that can metabolize oil spilled into the sea - or plants that take up radioactive compounds. And such amazing life-forms are everywhere. Ari Daniel discovered some scientists who are wading into a rust-colored ditch in Maine to find a whole ecosystem of unusual life forms.

DANIEL: When you think of life on Earth, plants and animals probably spring to mind. But there are species so odd – so unexpected that you’d never even dream them up. And yet, they’re often thriving in the most ordinary of places.

[CAR DOORS CLOSE]

DANIEL: David Emerson parks his car at Ocean Point in Boothbay, Maine, and we hop out.

DANIEL on tape: So it’s kind of picturesque, and we’re on the side of the road standing next to kind of a ditch.

EMERSON: Exactly.

DANIEL: You brought me to a ditch.

David Emerson and microbiologists sampling iron-oxidizing bacteria (Photo: Ari Daniel Shapiro)

EMERSON: I brought you to a ditch! But it’s a unique ditch.

DANIEL: The ditch is filled with water the color of bright rust.

EMERSON: It looks like just rust and goo, and it is in a sense, but, I mean, this is all bacterial.

DANIEL: Ditches like this one are right up Emerson’s alley – he’s a microbiologist at the nearby Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences. And he studies the bacteria that produce this rusty goo.

EMERSON: So we’re primarily looking in this site at an organism called Leptothrix ochracea.

Microbiologist David Emerson’s lab (Photo: Ari Daniel Shapiro)

DANIEL: It’s a kind of iron-oxidizing bacteria, and these microbes have been pulling off an incredible feat for the last two to three billion years. They survive by feeding on the iron dissolved in particular water flows. It’s something that’s incredibly hard to do, because iron has so little energy.

EMERSON: And so that’s one of the reasons they’re interesting to us, is finding the most minimal amount of energy that an organism can use to survive.

DANIEL: Most people familiar with these bacteria, though, are not impressed. They tend to be annoyed.

EMERSON: Yeah, so I mean, these are organisms are pretty heavily involved in fouling and corrosion of water pipelines.

DANIEL: There have been episodes when people turned on their taps and orange water gushed out.

EMERSON: The entire system had gotten clogged with iron bacteria.

DANIEL: But they’re not all bad. Once the bacteria feed on the iron, it turns to rust, and that rust can grab onto stuff floating by – like arsenic, other harmful metals, even viruses. In other words, these bacteria can actually help filter water. And that rust – it’s remarkably delicate.

Microbiologist David Emerson (Photo: Ari Daniel Shapiro)

FIELD: I do find it beautiful. OK, so if we bend over right here...

DANIEL: Erin Field – a microbiologist in Emerson’s lab – crouches down on one side of the ditch.

FIELD: We have this nice, fluffy, light matte. Like if you pulled out part of a pillow, it kinda reminds me of that. But then, you see within it, we have this really dark orange, almost looks like crumble topping, kinda like on a coffee cake.

DANIEL: So, in other words, in this ditch, we’re looking at an incredibly complicated ecosystem.

FIELD: Yes, we really are.

DANIEL: Another microbiologist – Emily Fleming – walks over to the ditch.

Fleming: What makes them special for me is that when you look at them under the microscope, they make these amazing structures of either tubes or twisted stalks.

DANIEL: Fleming says that until recently, these bacteria were impossible to grow in the lab. It turns out that a ditch is a surprisingly complicated thing. So most of what we know about the bacteria dates back to the 1830s when they were first discovered.

FLEMMING: So this leaves a huge area for us to be able to explore. It’s a mystery right in front of our eyes.

DANIEL: Recently microbiologists have figured out how to grow a handful of these bacteria species outside their natural habitat.

[LAB NOISE]

DANIEL: Back in his lab, Emerson is surrounded by vials and petri dishes, each one containing a small rusty sunset.

EMERSON: And so you can see all the rusty goodness, we call it.

DANIEL: Some of these bacteria belong to the genus Gallionella – they were collected from that ditch in the spring. Emerson’s also got a handful of Zetaproteobacteria species that he discovered on the seafloor near Hawaii. He feeds his bacteria steel dust and makes sure they get just enough oxygen. The result is a lot of happy microbes. There are still many species that refuse to grow in the lab. And there are basic features of all these bacteria that Emerson and his team just don’t understand. Like how exactly they feed on iron. Or what things all these bacteria have in common. And this is where a relatively new technique comes in – something that Bigelow Lab is becoming expert at. Sequencing the DNA from a single cell. Heres’s Erin Field again.

FIELD: It’s a really cool technique because it’s the only one currently where we can get DNA, and directly link it to a specific cell.

DANIEL: In the past, scientists needed lots of cells to get enough DNA. Now they need just one to spool out and read off the contents of an entire genome. Emerson says the technique’s being applied to all sorts of microbes that are difficult to grow in the lab.

EMERSON: That’s the beauty of these technologies that we have – is that we are now able to ask questions that we just never could before. And that’s a really powerful tool for understanding this unseen world that is really a very important world to the functioning of the planet.

DANIEL: Emerson says it’s just a matter of time before we figure out how to harness these bacteria to improve our world – by filtering water, building mini-structures out of rust, and catalyzing reactions. Not bad for a group of bacteria dining on iron in a roadside ditch. I'm Ari Daniel.

CURWOOD: Our story on iron-oxidizing bacteria is part of the series, One Species at a Time, produced by Atlantic Public Media, with help from the Encyclopedia of Life.

Related link:

Follow David Emerson’s research

[MUSIC: Iron Oxide: Curtis Mayfield “Kung Fu” from Get Ready: The Curtis Mayfield Story (Rhino records 1996)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the call of the wild far north - ice, fish and gold. That's right ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ivan Boogaloo Jones: You’ve Got It Bad, Girl” from Sweetback (Ubiquity Records 1999)]

Gold-Mining in Alaska

Taku Glacier and Taku River could possibly be affected by the mining project (National Weather Service)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Five major mining projects have been proposed for the transboundary watershed – the waters shared by British Columbia and southeast Alaska. The region is home to important salmon producing rivers that originate in British Columbia and run through Alaska to the sea. A number of environmental groups, Alaskan Natives and commercial fishermen strongly oppose some of these mining developments across the border. They argue mining could have negative impacts on the salmon and water quality, and irrevocably alter the region's economy, environment and way of life. Chris Zimmer is Alaska Campaign Director for Rivers without Borders, and he joins us on the line to discuss the proposed mines. Welcome to Living on Earth, Chris.

ZIMMER: Thanks for talking to me today.

CURWOOD: Chris, tell me, why is this transboundary watershed areas so important?

ZIMMER: These major rivers that begin in British Columbia and flow into southeast Alaska are really the life blood of the region. The rivers in total in the region support a salmon fishery and trout fishery that’s probably worth over $1 billion and then you also have customary and traditional fisheries that feed people, that support them. The forest is built on those fish...the bears and everything else in those forests live off the salmon. Without those rivers, southeast Alaska would be a vastly, vastly different place.

CURWOOD: Now let's focus on the biggest of these five proposed mines. It’s the KSM mine. Please describe what's proposed?

Alaska and British Columbia transboundary watersheds affected by the mining (Photo: Rivers without Boundaries)

ZIMMER: I think when you look particularly at KSM, it's the wrong mine in the wrong place. This is a mine with three open pits and an underground mine. One of the biggest mines in the world, probably the deepest open pit in the world. It would have several major tailings dams to contain all the waste rock and tailings which would be about several billion tons with incredible amounts of acid mine generating and heavy-metal generating rock...it would have to be contained for centuries if not forever and it's right above one of the premier King salmon rivers in the region. If this was somewhere in the middle of a dry desert it would be easier to manage this, but you have an incredibly wet environment with very productive salmon fisheries, very remote challenging mountainous terrain subject to earthquakes and glaciers, accidents and problems are going to be very difficult to clean up. KSM also proposes an unprecedented level of water treatment...seven of the probably biggest water treatment plants on the planet that would have to treat up to 118,000 gallons of polluted water per minute, and the question we tried to put in front of the Canadian government is what are the long-term overall cumulative effects of all this development and how can we make sure they’re addressed now rather than later? And that question still seems to be hanging out there.

Mining could threaten the ecology of Iskut River, home to salmon populations (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Mining folks say that they’re going through a long permitting process to ensure they won’t cause an environmental disaster now or in the future. Why are you not reassured?

ZIMMER: There is no requirement in the BC permitting processes for the Canadian or BC government to accommodate Alaskan concerns. They can listen but they don’t have to do anything. So a permitting process is designed to permit these mines, it’s very short term, and it just is not taking into account a lot of these long term issues, like the storage of the tailings. One quick example in the Taku river near Juneau, that’s also an acid mine. It was abandoned in the 1950s, and it’s been spewing acid mine drainage into the river since the 50s. We were told by the company and the BC government that the permitting process would stop that pollution, yet it still continues. The company’s under a number of pollution abatement orders. They built a water treatment plant that they promptly closed, so here we have a real world example of how things should be better and how mining should be cleaning up its mess, and it just isn’t happening.

CURWOOD: So from the Takeuchi what environmental effects have you seen there, and what efforts have there been to reduce or eliminate the acid effluent?

ZIMMER: We have seen a large dead zone downstream from the mine where nothing seems to live because of the toxic contamination. Part of the issue is we haven’t seen the studies done to actually determine the effects, you know, where is this pollution ending up? Is it getting into the juvenile salmon, which are really the main issue here, not the adults. Is it killing off the invertebrates and the bugs in the stream bottom that salmon live off of? So, these are very sensitive watersheds. They’re incredibly rich in salmon and wildlife. They have incredibly pure water quality, but they can’t sustain the impact from mining and still continue to be that productive here, so if we see heavy metal contamination in these rivers that eventually leads to serious problems for fish and everybody who depends on them.

CURWOOD: Now, how involved has the state of Alaska been in terms of this mine permitting process across the border from British Columbia?

ZIMMER: Apparently the Department of Fish and Game and the Department of Natural Resources up here have some kind of endless blind faith in the BC permitting process, and they seem to think that everything is alright and that the permitting process can take care of it, and we simply disagree. The track record with the Takeuchi has shown that that’s not the case. The engagement from the state of Alaska has been minimal, and in fact, the engagement from the state of Alaska in the KSM mine permitting process has been paid for by the owner of the KSM mine, and I think that puts you in an inherent conflict of interest if you’re a state agency trying to regulate mining, so we have been quite disappointed in the response of the state of Alaska and that’s why we’ve gone directly to our Congressional delegation, directly to the State Department to try to make this a federal government to government issue.

CURWOOD: So your motto is, there’s gold in them their hills...and leave it there.

ZIMMER: [LAUGHS] Well, there’s silver in the rivers as well, and if we keep the rivers well, that silver in the form of salmon comes back every year. You just have to manage them well, and we can have both. We can see some mining and continued fisheries, but it has to be done carefully here.

CURWOOD: Chris Zimmer is Alaska Campaign Director for Rivers without Borders. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Chris.

ZIMMER: My pleasure for talking with you.

CURWOOD: There’s more on our website, LOE.org, including comments from the Alaska Department of Natural Resources.

Kyle Moselle of the Alaskan Department of Natural Resources wrote in an email seeking comment on the KSM mine project.

"…the applicant has adequately responded to the State of Alaska’s comments to the technical working group for the proposed KSM Project. Seabridge provided us with more details on the specific types of fish habitat that would be lost in the British Columbia portion of the Unuk River from the proposed activities. The total fish habitat loss is estimated to be 383 m2 (a bit less than the size of basketball court), but we wanted to know whether the affected areas provided spawning, rearing, or migration habitat, and for which fish species. Seabridge has provided us with that additional information and referred us to the Fish Habitat Compensation Plan (EIS, Appendix 15-R) for information on the productive values of those habitats and the proposed compensation/offsetting measures for their loss.

The project proponent also responded with adequate information to answer our questions regarding regulation of waste water discharges and required financial security," (and) "has adequately answered our project-specific questions (see attached responses, which are also available on the EAO’s Project Information Centre website).

The Department has also met with representatives from Southeast Alaska Native Tribes, representatives of Southeast Alaska’s fisheries industry and conservation organizations.

I think that the project proponent and the Environmental Assessment Office have adequately responded to the comments, concerns, and input provided to them by the State of Alaska throughout the environmental assessment process. British Columbia has a capable project review process, and the Department of Natural Resources is happy to participate in it.”

Related links:

- A brief on the proposed mining project and its ecological effects from Rivers without Boarders

- Kerr-Sulphurets-Mitchell (KSM) project FAQ from mining company, Seabridge Gold

- British Columbia’s governmental approval status for the KSM mining project

- KSM Project Information Centre website

John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire

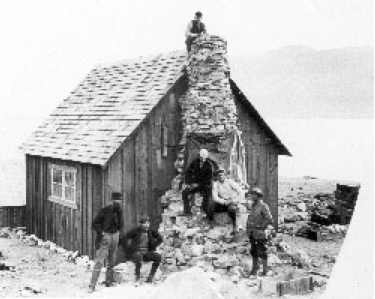

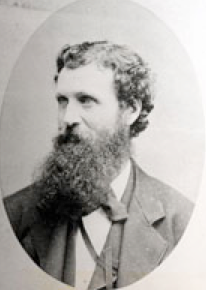

John Muir and geologists at his Glacier Bay cabin (National Park Service)

CURWOOD: Well, Alaska is a state of rare wild beauty that's increasingly also on the front lines of arguments about energy development and climate change. But the state also has a rare place in the history of American environmentalism, through no less a figure than John Muir. For most Americans, Muir is associated with Yosemite, the California state quarter bears his likeness along with an image of Half Dome. But John Muir might never have become an environmentalist without a visit he paid to Alaska. Author Kim Heacox posits in his new biography, "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire," that the wildest adventure Muir ever embarked upon was his canoe journey to what is now known as Alaska's Glacier Bay. We talked to Heacox on a rather scratchy Skype line at his remote Alaskan village.

HEACOX: Glacier Bay was instrumental in John Muir’s coming to Alaska. 250 years ago the bay was all glacier and no bay, and he heard about this bay, and he wanted to come up to Glacier Bay to verify his theories of glaciation, and he proposed this theory that the Sierra Nevada and especially Yosemite Valley had been carved by glaciers, and this was heresy at the time because the lead geologist at the state of California, Josiah Whitney, said the valley had been created by catastrophic downfaulting. And Muir had no scientific credentials, he was working in a lumber mill. In John Muir’s life the single greatest adventure he embarked upon was this 40-day canoe journey in October, November of 1879 with 14 Indians and a Presbyterian missionary to find the tidewater glaciers of Glacier Bay.

Muir Glacier (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Now, what was John Muir finding to be so capitivating about these glaciers in Alaska do you think?

HEACOX: Well, they’re massive, and they are still at work. You can see readily that the land is shaping them, and they’re shaping the land. Down in California, you have to use your imagination, try to imagine that a glacier once tried to build an entire valley, that glaciers once flooded this entire mountain range. When you go to Alaska, you see a landscape dominated by ice, where here and there mountain peaks stick through.

CURWOOD: What was it about Muir’s character that set him up for this kind of expedition and curiousity about glaciers do you think?

HEACOX: That’s a great question. I wrote in my book that Muir would be to glaciers what Jacques Cousteau would be to the oceans and Carl Sagan would be to the stars. If I have to pinpoint the turning point in John Muir’s life, it’s when he walked away from home, it’s when he walked away from his domineering father and the cultivated manicured world of Wisconsin and walked into the wild. He embarked on a 1,000-mile walk from northern Kentucky to the Gulf of Mexico. He worked his way down to the Isthmus of Panama, took a boat up to San Francisco, saw Yosemite for the first time - all profound experiences. If you’re going to walk away from your family, from your culture, from your community, from your nation, everything starts over again.

Glacier Bay (Photo: National Park Service)

CURWOOD: How important were Muir’s Alaskan trips for inspiring action towards establishing a national park and conserving wildlands?

HEACOX: John Muir redefines Alaska for America. The US had purchased Alaska in 1867. Secretary of State William Seward, and of course the media called it “Seward’s ice box”, “Seward’s folly”...it’s a sucked orange, the Russians have already killed all the sea otters, there’s no more good pelts, there’s no more money. And 12 years later John Muir arrives, sees what he sees as shimmering glaciers of Alaska. It’s magnificent, it’s beautiful, it’s not a wasteland, uselessness, a sucked orange. He goes back. He writes for the Overland Monthly Magazine and some newspapers. And he basically gives birth to the tourism industry in just a few short years.

Paddle wheelers and steam boats are heading up to Alaska from Puget Sound. Muir’s writings inspired Enos Mills who became the father of Rocky Mountain National Park. He was read by Robert Marshall, Aldo Leopold, Olaus Murie, the founders of the Wilderness Society, and on and on and on. Teddy Roosevelt, of course, Muir’s good friend, worked to create the Antiquities Act that passed in 1906 that enables Roosevelt by Executive Order with a stroke of a pen to create national monuments. And of course, they’re supposed to be these 25 and 50 and 100 acres sites to preserve antiquities. Well, Roosevelt ran with it, and he created these massive national monuments, Grand Canyon and Mount Olympus, that later became Olympic National Park and Grand Canyon National Park.

John Muir (Photo: National Park Service)

CURWOOD: By the way, this Antiquities Act was used initally to protect Glacier Bay, you write.

HEACOX: Yes, the Antiquities Act was passed in 1906, but Calvin Coolidge used in 1925 to create Glacier Bay National Monument, and the scientist who spearheaded the attempt to create the National Monument, William Cooper, he read John Muir when he was a little boy, wanted to be a mountaineer and a glaciologist like John Muir, so yes, you take the Antiquities Act from 1906 and many presidents have used it to create national monuments, and many of those national monuments have since become national parks.

CURWOOD: How was John Muir anonmalous for his time?

HEACOX: He was very anonmalous for his time. Today, we have people who are climbing Everest and Denali, and mountaineering and going on long extended wilderness trips. It’s a great thing to do. It’s regarded as healthy. Back in John Muir’s time, he was considered a kook. Nobody else was really doing what he was doing. For example, in 1890 on his third trip to Alaska, he was ill in California. And his wife knew he needed to return to the mountains to get well. He actually called it “mountain nourishment”. So he went to Alaska, out on the ice, he slept on the ice, he fell in a cravass, he soaked himself in cold water. After the fourth day, his cough was gone because he was so happy and in time people began to understand that this guy might really be onto something, that maybe we should set aside these wild places that are actually beneficial to us for our good health and wellbeing.

CURWOOD: If John Muir went to Muir Glacier today, what do you think he would see? How would he respond?

HEACOX: Oh, I think if John Muir went to Muir Glacier today, I think he’d be stunned. He knew glaciers were retreating, he knew the world was warming in his time, the late 1800s, early 1900s, Muir Glacier today is 32 miles further back from where it was in 1890 when John Muir built a small cabin in front of the glacier.

CURWOOD: Now, Muir engaged with President Roosevelt, as you point out in your book, President Theodore Roosevelt going camping with him at Yosemite. But how comfortable was he with Roosevelt’s brand of politics? Because Roosevelt brings in a Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot’s view was that the trees, well, that’s lumber, this is to be used.

HEACOX: John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt got along great. They greatly enjoyed each other’s company. They camped alone, they talked for hours into the night, the two guides that were with them listened in, they commented later that each man wanted to do most of the talking, they were both so exhuberant to tell the other one the way things are and the way things ought to be. And Muir, I guess you could label him, he was something of an idealist, a preservationist, he was not a utilitarian...and then Gifford Pinchot, the greatest good for the greatest number. John Muir would shake his head when he heard that little saying, and he’d go, “Yes. Right. All too often the greatest number is number one.” If you just keep adding more and more people and more and more technology and industry pretty soon you’re going to run out of these so called inexhaustible resources. It was called ‘the myth of superabundance’, and John Muir called it “gobble gobble economics”. He said nothing dollarable is safe. We have to come to a point where we have to just draw a line and say, “No, this place is sacred. It has value beyond utility.”

CURWOOD: You titled your book, "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire." What’s the fire?

HEACOX: The fire is the fire of conservation, fighting the hard fight. I think the glaciers of Alaska so inspired John Muir. Once you come to Alaska, the wildest place in his life he would ever visit, and you return to - let’s say, California, which is very hustling and bustling and people everywhere, much of it becoming settled very quickly and the forest being cut down. Once you have that looking glass of Alaska, everything else seems small and vulnerable. So he came back down from Alaska, and he said, something has got to change.

CURWOOD: Kim Heacox is author of "John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire: How a Visionary in the Glaciers of Alaska changed America." Thanks so much, Kim, for taking the time with me today.

HEACOX: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- More about Author Kim Heacox and his biography John Muir and the Ice that Started a Fire

- Learn more about the Alaskan rivers and glaciers Muir explored

[MUSIC: Muir: Bill Frisell “Beautiful View” from Big Sur (Sony Music 2013)]

Whooper Swans of Southern Iceland

Whooper Swan flaps its wings, trying to bear lift (Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Well, now we head from Alaska to Iceland, where early spring could pass for winter. Local guide Haukur Snorrason took writer Mark Seth Lender to see first hand what spring means for some wildlife at this unsettled time of year.

LENDER: Out on the lava field is a narrow pond glazed in half an inch of ice. A flock of Whooper Swans have spent the night there as the ice closed around them. And the open patch that remains is not enough. Breasting up and leaning all her weight against the leading edge, one of the swans works to make more room, and the frozen plates upend and slide. She peddles against them but nothing moves, and after a while she gives up. The cob only watches her, then stretches all the way down, rests his bill on the ice, does not drink or make a sound but only rests there (angry at someone or some thing) and only his reflection stares back at him. He straightens up, and the two of them side by side bow their heads staring, as if the ice is a mystery they do not understand. In accord, they flap and climb out of the water and onto the hard expanse. Having given up on breaking in, they will break out.

Whooper Swans shuffle and ice across the pond’s ice (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The flock shuttles across the pond. They shuffle and skid, the sound of their huge flat feet like children pushing through wet snow: sluice; slush; slis... Children is what most of them are, swans entering their second year their faces tinted warm reddish brown, and the grey-on-white of cygnets of the previous spring. Their calls grow closer, urgent, overlap. A pair of adults takes off. And like children, uncertain, half the remainder follow, half of them stay.

Wind comes… The rest of them go: a flutter of voices, the spank of wing tips, the buzzing of feathers chattering in white wings; and the jet black feet tuck under their tails.

A single Whooper Swan flies over an Icelandic lava field (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The ice slowly melts...

The sky grays out...

The first dull flakes come scudding in.

Nearby, at a vernal pool, its ragged edges slumping into the marsh, a pair of swans has stayed behind. They dip in the shallows trying to feed, weed trailing from their bills, striping their faces, thin shreds of translucent brown and green. They rove and bury in the small hard waves and the gusts lean into them, their feathers lifting like blades. They cannot stay.

[SOUND OF SWANS CALLING TAKING OFF AND FLYING]

Necks stiffen straight and long, then running on water they leap, skip, and with all the power they can bring to bear lift, flying low, crying as they wheel away....

Going to be a bumpy ride: Snowstorm coming. Nowhere to hide.

Whooper Swans avoid an approaching snowstorm (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

[MORE SWAN CALLS]

CURWOOD: Support for Mark Seth Lender’s fieldwork was provided by Iceland Naturally and Nature Photo Tours. There are pictures and more at our website LOE.org

Related links:

- Haukur Snorrason

- About Iceland

- Nature Photo Tours

[MUSIC: Jazz Soul Seven “Movin On Up” from Impressions Of Curtis Mayfield (BFM Jazz 2012)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, Abi Nighthill and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. We welcome Olivia Powers to our team, and special thanks this week to Dana Chisholm and Qainat Khan this week. Jeff Turton is our technical director. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth