"Good Fire": How Cultural Burning Heals Land and People

Air Date: Week of November 28, 2025

Cultural burning hands-on practice during a fire camp at First Nations’ Emergency Services Society of British Columbia (FNESS) in Cranbrook, BC. (Photo: Jordan Melograna, Indigenous Leadership Initiative)

Around the world, Indigenous people have been using fire on the landscape for thousands of years. One such practice comes from the Métis tradition in Western Canada. Cree-Métis scientist Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson is a senior fire advisor with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative and joins Host Aynsley O’Neill to share how this low-intensity “good fire” helps rekindle cultural traditions and cultivate healthier ecosystems.

Transcript

O’NEILL: To combat increasingly dangerous wildfires, modern fire management teams may use prescribed burns to reduce fuel buildup before fire season begins. But around the world, Indigenous people have been using fire on the landscape for thousands of years. One such practice comes from the Métis tradition in Western Canada. While a prescribed burn is typically a larger, low to moderate-intensity fire, the Métis burning practice is much smaller, more closely resembling a campfire, and it carries cultural significance. To learn more, we turn now to Cree-Métis scientist Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson. She's a senior fire advisor with the Indigenous Leadership Initiative. Amy, welcome to Living on Earth!

CHRISTIANSON: Hi there. Thanks for having me.

O'NEILL: So tell us, how did you get involved in this world of fire stewardship?

CHRISTIANSON: I just remember growing up having lots of my family involved in firefighting. Back then you know, we had fires all the time, but they weren't like scary fires. But I’d never actually really thought much about it until I moved down south to an urban center, and then I realized that that wasn't really like a normal life experience for a lot of people. And then I started really working with Métis elders during my PhD and just started hearing this concept of “cleaning the land.” And really got interested in rediscovering my own family's role in use of fire, but then also just how this could be a, you know, a potential solution for our current wildfire crisis.

O'NEILL: Now, many of us might be familiar with this concept of “prescribed burn.” How would you say that is both similar to or different from a Métis or Indigenous burning practice?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, so you know what, they're both very important practices but they're also like apples and oranges and so lots of people use the two terms interchangeably, but really they're very different conceptually, like for Indigenous people, like when we use cultural fire, it's around Indigenous governance systems and knowledge of when to burn, and it's done to achieve cultural objectives on the landscape, so things that we need to sustain our cultures. There's hundreds of reasons why Indigenous people burn. I mean, I think some of the most common and shared are, you know, burning for berries. So for example, berry bushes often get overgrown as they age, and when we go in with fire in the early spring or late fall, it's almost like pruning those berry bushes. You kind of burn the dead parts of them that aren't producing, but you leave the roots intact. So then the next spring, they put up really healthy new growth. And then for cultures that rely on bears, the bears are attracted to the new berry growth. So it almost like lures the animals into that area. And then in the end of the summer, you know, you get really nice fat bears to harvest. Prescribed fire is done for quite a different reason. It's usually to reduce hazard, so to, you know, remove vegetation and other things. It also generally follows quite a paramilitary approach. You know, it's dominated by white men, and, you know, there's lots of equipment and helicopters and, I mean, there's nothing wrong with that. The fires that they're doing are usually higher risk than the cultural burns that we do. So they're both very important practices, but just quite different in how they're actually carried out on the land.

Prescribed burns are large-scale operations requiring permits and careful planning. These burns are higher-risk than the Métis practice, and are carried out by teams of firefighters and may involve the use of helicopters to ignite and put out the fire. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: How did colonization change burning practices across Canada?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, so when settlers first came to Canada, they saw trees back then as money signs, right? They didn't understand, you know, why you would want to potentially burn in an area. So they brought these fire exclusion policies, and the first one in Canada was actually in 1610, in Newfoundland. So that made Indigenous burning illegal. And then there was also, like, the campaign of systemically removing Indigenous people from their lands. So through the Indian Act we have in Canada, through putting people onto reserves, through residential schools, all of those things basically led to this huge severance of our knowledge systems.

O'NEILL: And what kind of pushback have you faced against these cultural burning practices over the years?

CHRISTIANSON: You know, there's all sorts of Acts and regulations and other things in place right now that keep us still from burning as we need to do on the landscape. Even amongst our communities, there's a reluctance or a fear of fire, because we've been told for so long that that's not an appropriate practice to carry out on the land. So I think for me, you know, that's been one hard thing to watch, because we need fire. We need fire on the landscape, and what these out-of-control fires are showing us is that we're not stewarding forests properly.

O'NEILL: I'm curious how you would say your participation in burns is tied to or influenced by your relationship with the forest or nature just on a general level?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, you know, I think that it's implicitly tied. Because if you don't have that relationship, you don't understand why fire would be needed, and you don't understand then how that vegetation and other things might respond to fire. Like, one thing that's really important for us when we're using fire is, you know, thinking about nesting birds and other things, if we know that they're there we don't want to burn that area, right, because we're basically burning up their nests. So there has to be, like, that cultural tie to the landscape. When I go burn too, like, usually I go with my husband and my kids, it usually takes us two or three hours, so kind of an afternoon activity. We don't use, like, a ton of water, anything, because we have, like natural fire breaks, like snow lines or other things there. Actually, my daughters, I think, kind of find it boring, like after you like light it, because it's like a very, very controlled activity. And so that's one thing I often hear as a criticism for cultural burning is that, like, there's no training required, or there's no planning required, and that's incredibly insulting, because for us, like the training comes from, you know, years of working with people who are more knowledgeable than us with fire, and then, you know, the planning is done endlessly. It's something that we're constantly looking at and observing the land as we decide when and where to put fire. The positive side is, you know, that I just love being out there, and just because cultural burning is a slow activity you like, here are the birds, you notice the trees. Like, I'm pretty familiar with most trees on my property, which I know people might think is crazy, but like, I know, like, you know, I can see them and I can tell if they're like sick or if things are, are different about them. So that's the thing I like most, is just being out there and continuing that relationship.

When Métis people put fire onto the landscape, it’s on a much smaller scale than most prescribed burns, often described as a fire you can walk beside. (Photo: Jordan Melograna, Indigenous Leadership Initiative)

O'NEILL: And now, of course, many of us do consider fire frightening, dangerous. How do you protect yourselves from the potential dangers of being around large-scale fire?

CHRISTIANSON: So I think for us, when we're talking about cultural fire, it's usually a fire we can walk beside, is another term that we use for it. So like, when we go out, it's almost like a campfire moving across the ground, like that's about the scale of it. So for me, like I don't feel scared or like it's dangerous, it's really kind of quite a nice calming practice that we do. Most cultural burners I know have never had an escape fire, but you always have that in the back of your head like, well what if, and so I would say that I burn with way more caution than I used to, because of this and because of my role in like the advocacy components of it. You know, for me, what that does is because we're removing that dead, dry vegetation from the landscape and promoting a healthier environment, that's really where then when we see these out of control fires, it's much easier to stop the fires. So, you know, as a fire is coming towards my area, because I have burned and we have, like, a lot less dead vegetation that the fire can basically eat as it's moving towards us, it makes it easier for firefighters then to put out the fire. So, yeah, it's proven to reduce wildfire risk to communities from out-of-control fire.

O'NEILL: So your podcast is called “Good Fire.” What is good fire?

CHRISTIANSON: So with good fire, you know what we're trying to do is produce like a mosaic landscape. You know you have old growth forest and you know older trees, but then you also have, like, meadows, and you have younger trees, and you have a mix of deciduous trees and coniferous trees, so like leafy trees and needle trees. And the reason we do that is so that we have less far to travel to access, like the cultural resources that we need. And when I'm talking about bad fires, what I'm talking about is these like climate change-induced fires that are burning at such high intensity and with such severe impacts that they're really devastating the forest for generations.

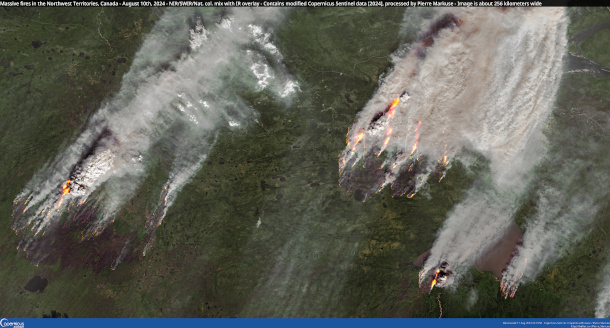

Satellite imagery of smoke from wildfires spreading through Canada’s Northwest Territories, August 10, 2024. (Photo: Pierre Markuse, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

O'NEILL: And now your fire knowledge is not just from Métis cultural practice. You also have a history with Western-based science education and research. How have you combined those two, the Indigenous practice and the Western practice?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, so I did my PhD, actually with the Métis community, learning about cultural fire and then I went and worked for the Canadian Forest Service and there I was a fire social scientist for almost 14 years. And so what I found was, when I started, I was very idealistic, and I thought, you know, if we just have, like, a really good Western scientific paper or something like that, it'll change people's minds and let us be able to start burning, and so I would say that we've produced paper after paper on that and have actually seen very little change. And what I then realized is really it's an issue of power and systemic racism that we're experiencing. It's not a lack of scientific knowledge or Indigenous knowledge. It's really much bigger things at play that are keeping us from being on the land. A lot of discussion about, you know, how we allow Indigenous people to burn, but really, like, burning is an inherent right, it's not something that people allow us to do or not. So I got offered a position at Indigenous Leadership Initiative, which is really an advocacy-based conservation organization that's Indigenous-led. And so here we're really trying for action now, so to really target policies, regulations and other things that are keeping us from being able to burn. And so we're not obsessed with fire. We're obsessed with like, healthy landscapes, and fire is one way that we can get to that. And you know, when I'm even speaking about cultural fire now, like, I show videos behind me of cultural fire, because usually once you show it, then people are like, I had one lady come up to me and be like, oh, that's all you want to do. And it's like, yeah. Like, it's not like, you know, we want to go and start like, you know, mountainsides on fire, although maybe there's some elders that eventually would want to do that. But you know, for us, it's just having a lot of fires on the landscape that are small and are controlled that produce these mosaics that we want to see.

O'NEILL: And in what ways have you seen successful collaboration between various different Indigenous groups and also perhaps non-Indigenous groups when it comes to fire management?

Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson is Cree Métis, and grew up in Treaty 8 territory in Northern Alberta. She is a Senior Fire Advisor for Indigenous Leadership Initiative and co-hosts the Good Fire podcast, which looks at Indigenous fire use around the world. (Photo: Jordan Melograna, Indigenous Leadership Initiative)

CHRISTIANSON: Yes I think probably the best example is I've worked quite a bit with the Blood Tribe over the last five years. So they're down in southwestern Alberta. Alvin First Rider and his team there have been working really hard to establish a fire guardian program, and they've done that in partnership with Parks Canada. And I think what's been great there is that Parks Canada has been a really good supporter, but not trying to control, if that makes sense. And I think part of that is because, at the moment, the guardians aren't trying to burn directly in the national park, but they've been coming out and supporting burns on the reserve, and it was a really great experience working with them. And the Blood Tribe program has just been inspirational and I hope that we see it replicated across Canada. You know, because of the changes to the forest and climate change in many areas like we can't just go out and put cultural burning back on the landscape like we used to. Those areas need either a prescribed fire or mechanical thinning, or hand thinning to remove a bunch of that vegetation that's in those areas because if we went and tried to do a cultural burn there using the techniques we usually use with community, it would just be way too big of a fire for us to control. But to me, that also speaks to where really good partnerships can come in, you know, like if an agency that has access to heli torches, you know, where people don't actually have to be in the fire, they can just drop fire into an area and they have all the firefighting equipment and other things, if they can go into those areas and burn them first, then we can slowly begin to bring cultural fire back to that area in a safe and sustained way.

O'NEILL: And how can this Métis burning practice be a tool for healing or cultural connection among Métis people?

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah. So I really think the beauty of it is just getting people out on the land together and really being proud of their culture. So any workshops that we've had where we've brought Métis people together, it's just been a wonderful experience, especially we've done a few with youth, where we go out and, you know, teach youth about why this practice was important. And most have really no idea that Métis people used to burn like this. It was an important part of the buffalo hunt and trapping. The other thing that I've really liked about it is just being able to work so closely with like our relatives, like the First Nations, because really, you know, we're related to those folks. We use fire in similar ways to them, and it's really been a wonderful, like, way of unity, if that makes sense. Like there's so many, you know, divisive things in the world, but when you really get people out on the land and learning and being with one another, it really helps, and for, you know, mental health, physical health and other things of people who participate.

O'NEILL: Dr. Amy Cardinal Christianson is a senior fire advisor for Indigenous Leadership Initiative. Amy, thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

CHRISTIANSON: Yeah, thanks for chatting with me.

Links

Métis National Council | Video: "Métis National Council Wildfire Workshop"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth