NYC Recycling Food and Yard Waste

Air Date: Week of July 18, 2025

New York City generates roughly 24 million pounds of trash daily. Approximately one-third of that is food and other organic waste. (Photo: Niwrat, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

A few months into New York City’s mandatory curbside composting policy, there are still some kinks to work out, and enforcement and fines have been temporarily paused. Eric Goldstein, the New York City Environment Director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, catches up Host Aynsley O’Neill on how the program is going and why composting food and yard waste can save money, benefit landfills, reduce NYC’s carbon footprint, and help gardeners.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

O’NEILL: And I’m Aynsley O’Neill.

New York City is the most densely populated city in America, and home to more than 8 million people. Now, multiply that by the 400 pounds of food waste generated per person per year, and suddenly the Big Apple doesn’t seem so fresh. Food waste has long been a tough issue to tackle, and while composting isn’t new to New York City, a recent mandatory curbside composting policy may finally give it the momentum it needs to make real progress. Enforcement began earlier this year before being paused, and a few months in, there are still some kinks to work out. Currently only one-fifth of collected food waste actually makes it to the composting facility on Staten Island. But the scraps that are sent there not only help landfills reduce their carbon footprint, the compost itself is given away to NYC residents, who can then use it to close the circle and fertilize their gardens or window boxes. To understand the ins and outs of NYC’s new program, we called up Eric Goldstein, the New York City Environment Director at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Eric, welcome to Living on Earth!

GOLDSTEIN: Thank you, Aynsley, nice to be here.

O'NEILL: So as awareness around sustainable waste management grows, composting is increasingly taking a sort of center stage. So what are the key benefits of composting? Why is it important?

A mandatory composting program by the New York Department of Sanitation that began in 2025 requires residents to properly dispose of food waste in designated bins. (Photo: T Dorante, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

GOLDSTEIN: Well, composting is one of the most important pieces of the nation's unfinished solid waste agenda, and right now, most of the food scraps and yard waste that we generate is sent to landfills and incinerators. Both of them are problematic. In landfills, when organics are buried, they break down and decompose and generate methane, which is a very potent global warming gas. And if we send food scraps and yard waste to incinerators, and we're not big fans of incinerators anyway, but since they have such high moisture content these food waste and yard waste, they foul up the burning process. It's like throwing a wet log onto a campfire, and so it cools the temperature and generates more pollution in the local areas where those incinerators are sited, and that's often in environmental justice communities. So neither landfilling nor incineration are the place where food scraps and yard waste ought to be going. Organics are the single largest portion of the nation's municipal waste stream, and we can handle them sustainably, and that will be a plus for our environment, our air quality, climate change, as well as saving taxpayers money. And in contrast, when we send our organic materials to a composting facility, we turn those materials previously thought of as waste into finished compost that can be used as a natural fertilizer to help in the growth of street trees, plants, community gardens, and we've taken a material thought of as a waste product and turned it into a useful material that helps us live more sustainably.

O'NEILL: And New York City decided they wanted to buckle down on composting. So what exactly does mandatory curbside composting mean for New York City residents?

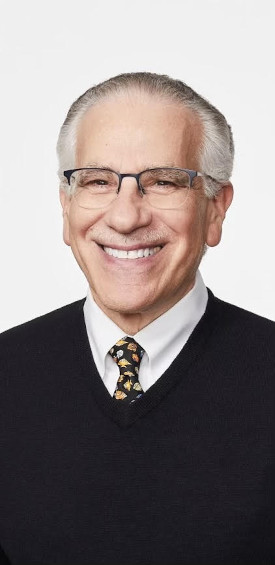

Eric Goldstein is a senior attorney and New York City Environment Director at the Natural Resources Defense Council. (Photo: Courtesy of Eric Goldstein)

GOLDSTEIN: Well, New York is now the largest city in the nation that has curbside collection of food scraps and yard waste and so on a weekly basis, just as the city officials in their sanitation trucks come around and collect the ordinary trash and recyclables like metals, glass and plastic, they are now collecting organics, food scraps, and yard waste separately so that they can be composted and turned into a useful end product.

O'NEILL: And Eric, at what point do people start to get fined or penalized for not complying with this program?

GOLDSTEIN: Originally, enforcement started earlier this spring, but several elected officials noted that there had been insufficient public education activities and not enough people knew about the program, so the sanitation department has chosen to hold off on enforcement until the end of the year, and that's just fine, because the objective is not to generate money from this program from fines, but to get broad participation. The challenge will be to make sure that we use these next six months to educate all New Yorkers as to the importance of composting and how to participate in the program. So we expect that fines will return, starting at $25 in January.

O'NEILL: And what were New York's composting options before this decision? So I'm personally based out of Boston. You can apply for compost pickup in certain buildings, or you can bring your compost to a drop off site. What options did New York have beforehand?

GOLDSTEIN: Up until now, New York has primarily relied on drop off locations and community composting. We've had a very vibrant local group of citizens who have operated in community gardens and small scale composting sites around the city, and that's been critical for education and for getting kids involved in nature. But you've had to really been committed to the program by taking your materials there and dropping them off.

A key facility for NYC’s collected food waste program is the Staten Island Composting Facility. (Photo: Michael Appleton, Mayoral Photography Office, Courtesy of DSNY)

O'NEILL: So how important do you think it is for New York to choose composting through a sort of voluntary or community driven interest, as opposed to a system of penalties and fines?

GOLDSTEIN: Yeah, it really shouldn't be an either or. Both of them are essential. The community composting efforts that have been underway in this city, in neighborhoods across all five boroughs for years and years, have really been fundamental to building up support for composting. They've taught kids about nature. They have in addition to their environmental benefits, they have played a key role in neighborhood revitalization, and so community gardens, community composting, dealing with food scraps in your local neighborhoods, has been a very effective way of getting people involved in nature, addressing the issue and producing the fewest amount of global warming emissions because you're eliminating the transportation costs associated with shipping tons and tons of food waste, you know, hundreds of miles to out of city locations. So there's no substitute for community composting because of all of its environmental benefits and neighborhood revitalization benefits. But ultimately, if we want broad scale participation, we have to make it convenient for residents, and that means collecting it at curbside for those who don't choose to participate in community composting programs. So both are essential. Both are mutually supportive, and both are among the most significant actions all of us could take at home to take a bite out of the climate crisis.

O'NEILL: Well, because Eric, I can only imagine that in a world where the city did not make composting mandatory, it wouldn't suddenly happen that every single New York City resident would wake up one day and go, now I really should be composting, shouldn't I?

GOLDSTEIN: Well, that's correct. It does require an educational effort to explain to people anywhere why you are asking them to take an extra step, an extra minute, and separate their waste into various piles. We know it makes sense economically. Cities that have advanced composting, like Seattle, San Francisco and Portland, they are actually saving money for every ton of food scraps and yard waste that they send to a composting facility, rather than to a landfill and incinerator. So we know it makes sense to compost, but if we want to get everybody to change their behavior, we've got to educate them and explain why it makes sense and how to participate and recognize that that transition will take a little time.

O'NEILL: Well, and this program was rolled out in the five boroughs less than a year ago. So what kind of challenges have you seen or dealt with since then?

Food and organic waste that does not go to the NYC composting facility may end up in wastewater treatment plants. (Photo: Rznagle, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

GOLDSTEIN: Well, like every other thing that we ask New Yorkers to try to do, it's going to take some time to build up full participation. The latest numbers that have come out have suggested that as much as 10% of the food scraps and yard waste that had been previously thrown out and gone to environmentally problematic landfills and incinerators is now being sorted for composting, and that's a good start.

O'NEILL: And as I understand it, the Department of Sanitation has said that a certain amount of collected waste gets sent to a wastewater treatment plant in Brooklyn. What's the story there?

GOLDSTEIN: Well, one other thing that can be done with organic material is to send it to something called an anaerobic digester, anaerobic means in the absence of air. And these digesters are big tanks that are sometimes located at sewage treatment plants, because organic material sewage waste is also an organic material. And so these facilities can capture some of the methane rather than having it escape if you bury food waste in landfills. So on the one hand, sending food scraps to an anaerobic digester is better than burying it in a landfill or trying to burn it in an incinerator. But if you try to mix these food scraps and yard waste with sewage sludge at a wastewater treatment plant, that's problematic, because then you can't use the residue, the sludge that is left over as compostable material, since it's got all of these bad things that end up in our sewage sludge. So, while sending food scraps and yard waste to wastewater treatment plants for anaerobic digestion may be better than sending them to landfills or incinerators, by far and away, the best thing we can do is take all of this food scraps and yard waste and send it to actual composting facilities to be turned into finished compost that can be used to replace chemical fertilizers.

O'NEILL: So Eric, what else would you like listeners to keep in mind when it comes to how we deal with our food waste?

GOLDSTEIN: Well, as important as composting is, the absolute best thing we can do with our food scraps is to generate less of them in the first place. So donating edible food to food pantries, buying only the food we need and will use, putting on our plate only what we can eat. These are ways in which we can address the food waste problem most sustainably, and by doing so, we're also helping address another major problem facing America, which is food insecurity. And so by taking the food that we have that is still edible and making sure that it gets to people who are food insecure, we can be not only addressing the environmental problem but also meeting the needs of people who are food insecure.

O'NEILL: Eric Goldstein is the New York City Environment Director at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Eric, thank you so much for joining us today.

GOLDSTEIN: Thanks for having me.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

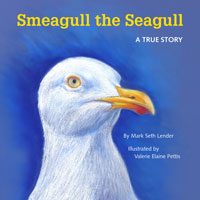

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth