Natl Audubon Keeps Enslaver’s Name

Air Date: Week of March 31, 2023

A portrait of American ornithologist, naturalist, painter, slaveowner and white supremacist John James Audubon. (Photo: White House Historical Association, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

The namesake of the National Audubon Society was an enslaver, racist and white supremacist, so several local chapters are changing their names. But the leadership of the national group has rejected making a change. DC chapter President Tykee James joins Host Steve Curwood to say the decision is an obstacle to a more inclusive birding community.

Transcript

CURWOOD: The National Audubon Society, formed in 1886, is one of the oldest environmental organizations in the United States. The bird conservation group was named after naturalist John James Audubon, author and illustrator of The Birds of America, widely considered one of the best ornithology books ever created. Mr. Audubon also bought and sold slaves, actively advanced research designed to boost the myths of white supremacy, and denigrated Native Americans and black people in his writings with the “n” word, even though some sources suggest his birth mother may have been of mixed race. The National Audubon Society recently voted to keep the name honoring Mr. Audubon despite pressure to distance themselves from his racist legacy. Several local chapters are in the process of changing their name, including the District of Columbia where Tykee James serves as President. Tykee has previously served on the government affairs team at the National Audubon Society and joins me now for more. Welcome to Living on Earth, Tykee!

JAMES: Thank you for having me, Steve. Always great talking with you.

CURWOOD: What did John James Audubon do that's so racist that you and many others think that his name needs to come off the society's masthead?

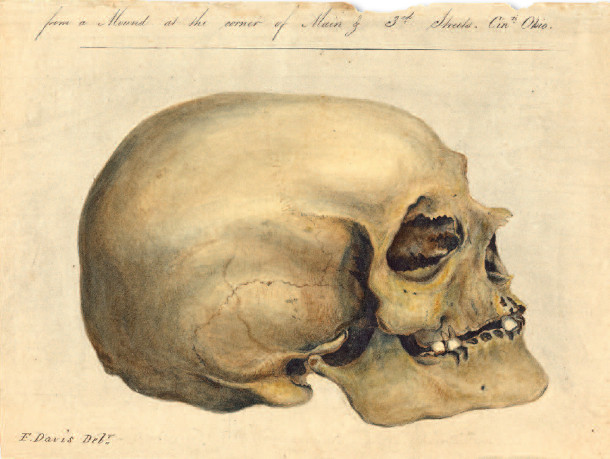

JAMES: The legacy of John James Audubon is based in enslaved Africans being enslaved upon his journeys and his perpetuation of indigenous genocide and he journaled and from his journals we can see what he thought we can see what he said about his own adventures. Using words that I wouldn't use to describe the people that he's around, that are black and indigenous. He's also used his position as a rich white guy in the mid 1800s, to make interactions with indigenous communities that led to violence and he collected a few skulls in that and not bird skulls, human skulls. What does it carry human skulls for? Not a guy that inspires from his work.

CURWOOD: I read someplace that John James Audubon worked with this guy Samuel George Morton, helping dig up bodies of black people to measure their skulls with the hypothesis that somehow the shape of skulls indicated that black people were inferior to white people.

JAMES: Well, I'm glad you brought that up, because it is an important reference to so many stereotypes and so many ways that folks understand race and how folks of different races are treated. A lot of it comes from that now you didn't have to study, you didn't have to go to any of Morton's classes to know this. But the belief that hypothesis, disproven, even though it was disproven and continuously can be disproven, that hypothesis is still carried in culture and in practices that we see today.

Lithograph from Samuel George Morton, Crania Americana. John James Audubon was among the scientists who stole human skulls from burial sites of Native Americans and Mexican soldiers. They sent the remains to Samuel George Morton, who used them in his racist science practices claiming that intelligence can be ranked by skull size. (Photo: F. Davis (engraver), Wikimedia Commons, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Public domain)

CURWOOD: Tykee what was your reaction when you learned that the National Audubon Society leadership had decided to keep the name, despite the rather loud sound of folks who are saying it's time to get rid of it?

JAMES: I first thought, okay, they did not consult chapter leaders, they did not consult members and it's in their statement. You know, it would've been very different if in their statement they had, we've heard overwhelmingly from members we've heard overwhelmingly from chapter leaders, and this is what we decided, no, they said, we talked to a couple people when we made this decision, and by the way here's 25 million to shut up about it. But after some digestion, I've reflected on the fact that it's one thing to inherit the name, right, I inherited the name when I took over part of the leadership at DC Audubon, I inherited the name, but I am not endorsing it, by choosing to keep it, I am not promoting it further by choosing to keep it. There were so many people who have been and hopefully still are rooting for the currently named National Audubon Society to see this differently at some point. And I honestly think it's a leadership decision, not a decision that represents the community, not a decision that represents the workers. And in fact, the workers who have organized their own union, I've helped organize it, now are calling themselves Bird Union as a placeholder name so that they can go through their own process of renaming an organization within the organization that better reflects their values and ambitions. The reality around seeing what inspires us is the important part of this because they talk about how the name is synonymous with bird conservation, I don't believe that for one second, I don’t believe that not for one minute. Maybe for a certain demographic and then that's, of course, what gets into why I see this as a leadership decision. Most of the people on the board, as well as in leadership, are old white folks. Who will google Audubon near me to find a local chapter, same demographic. And if that's a name that folks are familiar with, from a certain demographic, there's something that we should reflect on if that's also the reflection of their leadership, because that then doesn't possess an endorsement from the current or next generation of leaders that they're seeking to inspire and stay relevant to.

CURWOOD: You referred to the National Audubon Society's $25 million commitment over five years to fund equity diversity and inclusion and belonging work, which they announced the very same day that they were keeping the name Audubon. I mean, to what extent do you think that commitment makes up for the fact that they're keeping the Audubon name in your view and to what extent does it tell you that this is to please certain key donors?

Portland, Oregon’s Audubon chapter is among the many organizations moving away from the name Audubon due to the racist legacy it upholds. (Photo: Finetooth, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

JAMES: This is definitely about that but I also think that the $25 million being mentioned specifically on that day is easily one of the best, I hope it gets nominated for best performance of wokeness of 2023. You read their statement and I really encourage everybody to read it. It reads as discrete thoughts, not as a flowing document, it reads as like every person got one paragraph to say one thing about it. The lack of transition shows how short sighted a decision this is. This is very short sighted for an organization that wants to be relevant to the current generation and the next. There is no amount of money that can distract us from the additional wrongdoing that's taking place in that leadership at that organization. Mind you, what organization what company would make an investment in a department that hasn't had a department head for more than a year, for the last four years. They hadn't had somebody in that position for over a year. Twenty-five million dollars, zero leadership in that position. The workers have been doing the work, don't get it twisted, the workers have been doing the work. But if you don't have a vice president of equity, diversity and inclusion, and you're putting $25 million in it, is that $25 million gonna find somebody to lead it? Or is this going to be led by the same folks who chose to keep the name?

CURWOOD: Describe for me a bit of what is the work that you're talking about here? Why is Audubon important? Why is this work important?

JAMES: I've been watching birds for about a decade and when I worked at the National Audubon Society, I helped organize bird walks with members of Congress and congressional staff. I see that from my neighbors in West Philly, to congressional staff on the hill, everybody has a story about birds. And those stories about birds can be very powerful motivators to protect them and the places they need. Less stories about birds means we have less protectors. So to get more of those stories, let's make space for those stories because everybody has a story, but not everybody has a space for it. And I hope that organizations like the National Audubon Society, with all the potential it has for good realizes that it can still change its name and keep the mission. That's something that I think everybody will support.

CURWOOD: So what's your understanding of why they want to keep this name? I believe the National Audubon Society went on the record not so long ago, calling or at least joining the call for the removal of Confederate monuments that, of course are based on racism.

JAMES: You know, it gets back to the point I made earlier. If knowing better means doing better you don't have to do better if you don't feel like you're going to be held accountable. National Audubon Society, their leadership, they do not feel like they can be held accountable and I am very disappointed in that but not surprised. I've been part of the chapter network for a pretty long time I've been talking to other chapter leaders and a lot of us are taking our own steps towards renaming. DC Audubon is going through the process, Seattle Audubon is leading very, very well. Madison Audubon, Chicago Audubon, New York City Audubon recently just announced, Portland as well. So there are folks realizing that this Audubon name whether you're affiliated with National Audubon Society or not, this Audubon name has to go. There's no reason to keep this.

This sketch of the Louisiana Heron is amongst the many featured in John James Audubon’s most famous book, Birds of America. (Photo: Rawpixel Ltd., Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think that national Audubon's reluctance to let go of the name of this rather extreme and enslaver? If one looks closely at his record, he just wasn't sort of casual, he really was associated with people that had deeply racist beliefs. To what extent do you think that inhibits the mission of bringing more people into the birding community in the environmental movement? I mean, we've seen over the last 70 years a decline of 70% of the populations of animals across the board, birds populations are really crashed. So to what extent does this get in the way of getting more people to bird to become more defenders of bird to understand and participate in what I think you have called a time's the magic of birding?

JAMES: If you have to become a branded ambassador to an enslaver to protect the things and places you care about most, we are not achieving environmental progress. I believe firmly that there are no casual enslavers. That being said there are no casual enslavers. If you are taking away somebody's liberty and your legacy is based off of that, your family's wealth is built off that, this country's wealth is built off of that, well there's something that we need to examine in that, there's something that we need to look at and it's not just renaming things. It's disrupting the status quo. And at the end of the day, at the beginning of the day, we can't forget the effects that slavery has had on where we are today, you know, the aspect of Morton and pushing the hypothesis that brain size is intelligence and therefore there's an attachment to skin color, like that whole racial classification system that's been found false 20 ways to Tuesday, but why it remains in the culture it's because people don't always know where those ideas come from. So it's important to know where things come from because if you're just trying to attack this tree of evil, not good and evil, not even knowledge, just just evil and you're just pruning the buds you're not going to get to the root of the issue. So if you see me playing in the dirt, I'm not there to have fun, I’m trying to uproot this issue, and ignoring that, that's where National Audubon Society is.

CURWOOD: Tykee James is currently serving as president of the Audubon Society of the District of Columbia, and previously served on the government affairs team at the National Audubon Society. Thank you so much for taking this time with us today, Tykee.

JAMES: Thank you, Steve looking forward to talking to you again.

CURWOOD: National Audubon has said a name change would divert resources from their mission. Their full statement is on our website loe.org.

Links

Smithsonian Magazine “National Audubon Society Votes to Keep the Name of an Enslaver”

Audubon | “National Audubon Society Announces Decision to Retain Current Name”

Crosscut | “Amid Controversy, Seattle Audubon Changes Its Name”

The Guardian | “Bird Union Drops Audubon Name to Distance from Namesake’s Racist Past”

Common Place | ““WE LEFT ALL ON THE GROUND BUT THE HEAD”: J. J. AUDUBON’S HUMAN SKULLS”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth