The Hawk’s Way

Air Date: Week of May 6, 2022

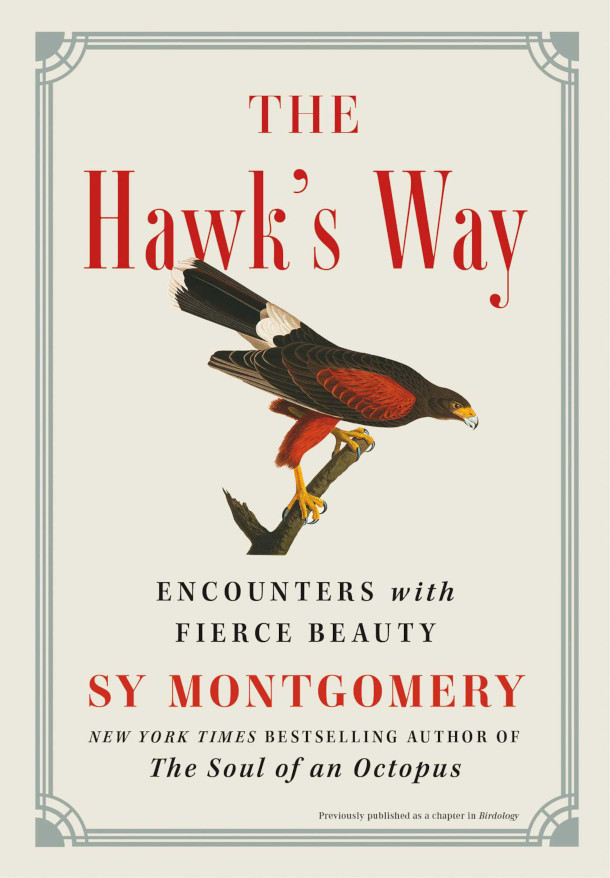

The Hawk’s Way: Encounters with Fierce Beauty is author Sy Montgomery’s latest book. (Photo: Courtesy of Simon & Schuster)

Falconry, also known as the practice of hunting with birds, can be traced back perhaps as far as the Ice Age. Many modern aficionados, like author Sy Montgomery, consider the sport to be more about the interaction with these hawks, falcons, and owls, rather than about the hunting itself. Sy’s newest book is The Hawk’s Way: Encounters with Fierce Beauty, where she talks about learning the art of falconry. Sy joined Host Steve Curwood for the latest Living on Earth Book Club Event to discuss the wondrous world of these birds of prey.

Transcript

Falconry or hunting with birds possibly goes back to the end of the Ice Age or even before, and it was common in ancient civilizations. Falconers traditionally worked with trained birds of prey to hunt game together and share the spoils. Today for people like author Sy Montgomery this sport is more about the joy of interacting with the birds themselves. Sy has written 29 books for children and adults, most about animals and the people who engage with them. Her latest is The Hawk’s Way: Encounters With Fierce Beauty. In it, Sy tells of learning the art of falconry from her mentor Nancy Cowan, from feeding these birds with parts of frozen baby chicks to understanding hawk psychology. Sy joined me for a live discussion as part of the Living on Earth book club at an event sponsored by New Hampshire Audubon and New Hampshire Public Radio. I asked her to describe how she felt the first time a hawk perched on her arm.

MONTGOMERY: It was like holding a waterfall or a lightning storm, or an eclipse on your glove. When Jazz, the first hawk to land on my falconry glove landed, I was shocked at how heavy she was. I was shocked at the squeeze of her strong yellow feet. I was completely filled up with the splendor and the wildness of his creature, like wildness itself had come out of the sky to me.

CURWOOD: I gotta confess, I wasn't sure about this book. Because Sy is famous as a vegetarian. And this book about the way hawks operate, it's about as far from vegetarian as you get! And in this book, you have the heads of these baby chicks are being chopped off, their legs are being chopped off, their hearts are being pulled out to become food for hawks in training. So, one of the recurring themes in this book is how your vegetarianism, you know, and your interest in falconry. I mean, like, you're at war with yourself.

Sy Montgomery (left) reads an excerpt from The Hawk’s Way to the audience. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

MONTGOMERY: Oh, yeah, that's right. I mean, the last person you would think, would practice falconry. If I found there was a steak on my plate, I would push it away. But when you're in the company of one of these magnificent birds, what you have is glory, what you feel is their hunger and their delight. What you feel is, there there's a word in falconry for their desire to hunt. And it's called yarak. And it's such an ancient word, no one really knows for sure where it came from. But a hawk lives to hunt, not just to eat, a hawk wants to chase and capture even more than it wants to eat. And that glorious desire, seeing that desire unfold and be fulfilled, that animal's joy can become mine. And to be able to understand or even come close to touching a mind, so different from my own.

CURWOOD: To somehow enter the heart and mind of a hawk?

MONTGOMERY: Well, this is what we want. This is what we always want with everyone, you know, with our friends, and with our family, and with the animals that you see, you want to know, What's it feel like to be you? I think it was kind of soul cleansing, for me, to let go of so much that was about me. It wasn't about me. It was about joining them and respecting that ancient drive and desire that hawks have, which really goes all the way back to the dinosaurs, because as you know, birds are dinosaurs. And all the dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, except for the ones who fly. And when you have one of these creatures on your arm, you're holding a dinosaur right there. They're not just descendants of the dinosaurs. They're descendants of a very small wing of the dinosaur clan, the theropod dinosaurs, the meat eating dinosaurs.

CURWOOD: From the little, from the velociraptor to the, dare I say, the Tyrannosaurus?

Sy Montgomery’s first experience with falconry was with Jazz, a four-year old female Harris’ Hawk like the one pictured. (Photo: John Rutter, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: That's right. Like T Rex. And you know T Rex when he hatched out of the egg. He was covered in down.

CURWOOD: Yeah. Let me ask a general question about birds in captivity. How do you feel about people keeping birds in captivity?

MONTGOMERY: It's hard to keep a bird in captivity and keep it happy. It's hard to keep a lot of animals in captivity and keep it happy. The thing about falconry hawks, though is if your hawk doesn't like you, it will fly away and you will not see it again. Because you don't just keep them on a string. Your hawk can disappear, and this happens. And I read, I think this was in one of Steve Bodio's excellent books, A Rage for Falcons, that he knows of wild hawks that would come out of the woods, never had any jesses on their feet, had never been in captivity and would join the hunter. Because the hunter makes a good junior hunting partner. So if that person will scare up game, the hawk figures out, bam, you know, this is someone I want to stick around with. And my falconry instructor Nancy Cowan was very clear that this is a voluntary association, that your hawk will just disappear if you don't measure up. And you can even be nice to the hawk and like the hawk, but if you're a lousy hunting partner, they're out of there.

CURWOOD: So, in this process of falconry, actually, you're working for the hawk. That you're the servant, you're the assistant, helping, but the hawk is in charge.

The Living on Earth Book Club hosted its first live, in-person event since early 2020 at the McLane Center of New Hampshire Audubon. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

MONTGOMERY: Totally in charge. And you cannot break their rules. All the rules are their rules. Nancy was very clear about this. And sometimes they will have rules that you don't understand at all. But they'll let you know when you broke them. Nancy had this one incident. Her husband, Jim Cowan, was a master Falconer, from whom she learned the art of falconry. And he had several hawks and she had her hawks, his and her Hawks. And one day it was their anniversary. She was all dressed up. Jim got home late. He wanted to take a shower before they went out to dinner. So he said Oh, would you feed my goshawk? Oh, sure. New goshawk, tell me what you usually do. He says you present the first chick, goshawk eats it. Present the second chick, goshawk eats it. Present the third chick, goshawk eats it, you turn around, you leave. Fine. So she does this. First chick goes fine. Second chick goes fine. Third chick is fine. She turns to leave. And then the goshawk fluid her face and stuck his talon almost through her eyeball. So it's a bad anniversary. So she was very annoyed when Jim finally emerged from the shower. And she wanted to know, what didn't you tell me? What did you forget to tell me. And the reason that goshawk had attacked her was that usually after the third chick, he would reach out, and fluffle, fluffle, fluffle on the birds chest. That was the routine. And she had not done the routine. And so the bird instantly felt like, oh, something's really wrong, I gotta go for the food and went for her face. And the amazing thing though, was that she was mad at Jim. She wasn't mad at the hawk. Because that's just what they do. So you've got to learn not to make a mistake. And if you make a mistake, you can pay. So you know, I was very, very careful with these birds. Another reason that you're careful is, more importantly than you don't want to get hurt, these birds, although they're tremendously strong, and some of them like the Peregrine can fly down like a lawn dart at 240 miles an hour, even though they have immense strength in their, in their feet, and their bills. And they have all these amazing superpowers. They're quite delicate, actually. And just if you have a hawk on your glove, just a funny little wind can lift a wing and hurt that hawk. If you're walking through the forest, trying to get some game and you fall. And that bird falls into you know, a twig that pokes in its eye, your bird can be blind, you can kill your bird with a mistake. So you got to be really careful that you do everything right.

CURWOOD: So how do you get these hawks? How do you get these predators, that you then become the junior partner of?

Falconry is the sport of hunting with birds of prey. (Photo: Tiarescott, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: Well, I never had a hawk at our house. I kind of had to choose between the hawk and my marriage. So my husband Howard considered a hawk like having a loaded gun in the house. He really didn't want it. So, that wasn't happening. But to become an apprentice, an actual apprentice. What you have to do in New Hampshire is you capture a red tailed hawk, it needs to be a bird of the year, it can't be an older bird. It needs to be a young bird because you know, this way you may help the population instead of just deplete it. 80% of young hawks die in their first year. If you capture a red tailed hawk for falconry, many of the falconers will release that bird at the end of the year and just let it fly free. And what you've done is given it a head start in life, because normally 80% will not survive that first year. And to capture it, there's a whole system of stuff that you need to do. I mean, first, you go to a place where you've seen hawks, and you get an unfortunate rodent, who is going to need therapy after this. And you can put it under what's called a Bal-Chatri, which looks kind of like a basket, but the hawk can see through, it's got a lot of holes, and it has all these little Velcro like loops on top of it. And the poor rodent is there, the hawk can see this very easily. From 1000 feet, they can see prey within a couple of miles. And it will come down to try to capture the rodent and its talons will get stuck. Meanwhile, you're hiding in your car or in the bushes, and you rush out and you detangle that bird and then you take it home, that's how you get them. After you've got your falconry license. You can also actually order birds from breeders.

CURWOOD: So, what is the nature of this relationship? And I mean, what's in it for the hawk? And what's in it for the falconer? What seems to me that, you know, us people were kind of opinionated, we want to dominate but in a way we are not at all dominated.

MONTGOMERY: No, it's true. What is in it for the hawk is I might be able to scare up game just by crashing through the underbrush. And my big heavy feet will make some vole or squirrel rush out. And this is why hawks will even get over their aversion to dogs. Most hawks hate dogs and will scream at the dog. You horrible thing, I hate you, go away, you're a dog! But once the dog points the game, and once they make that connection, like ooh, the dog's pointing the game. Now they don't want to hate the dog anymore. That doesn't mean they have great affection for the dog, but it means that they will tolerate the dog. But as far as what is in this for the falconer. I wrote about that a little bit.

Sy Montgomery (left) and Steve Curwood (right) have worked together on a number of stories, including an interaction with Octavia the Octopus at the New England Aquarium. (Photo: Chloe Chen)

CURWOOD: Just a little?

MONTGOMERY: Would you like me to read a piece of that?

CURWOOD: Sure.

MONTGOMERY: This is what I found was the greatest gift of falconry. Just like friendships with different people, relationships with individuals of other species have lessons to teach us. We are of course, deeply enriched simply by learning about life ways other than our own. I love it that some creatures I've been privileged to know can taste with their skin (octopuses), see with sound (dolphins and bats), and perceive colors that we can't even imagine (birds and reptiles). But animals also have much to show us about how we, as humans, can more meaningfully and compassionately encounter the wider world. Our fellow animals teach us lessons about the delights of sameness and difference. They immerse us in wonder. They lead us to humility. They inspire us to reverence. They teach us the many facets of love. The ancient Greeks said there were four kinds of love. The highest form of love was called agape. This is a love, untainted by expectations, a love without external reward. In the Bible, agape came to stand for the love God has for his creation. For the love humans should endeavor to feel toward the creator and worship. Agape asks nothing in return. This is what a hawk can teach you. How to love like a god.

CURWOOD: With a fair amount of reluctance I have to bring this to a close. This is such an amazing book. And you're such an amazing writer, but also such an amazing person. And you know, if you have small people in your life, by the way, there's a whole bunch of books that Sy has written, sometimes focusing on scientists who are doing stuff, written in language that's more accessible for younger people. And then of course, the prose that you've put together, whether it's The Good Good Pig or, of course, The Soul of an Octopus.

MONTGOMERY: Well, gosh, you know, you're in that book, Steve. One of the best scenes in Soul of an Octopus had Steve in it, because he came with his crew to meet, it was Octavia?

CURWOOD: Octavia, yes.

Sy Montgomery with her dog Thurber (right), as well as a friend’s dog (left). (Photo: Jay Feinstein)

MONTGOMERY: Yes. And Octavia pulled a fast one on us. All of us were there just lost in the excitement of touching her and feeding her and we had this bucket of fish and we were handing her fish and it was sliding down her arms to her mouth because her mouth was in her armpits. Of course, where else would it be? And so there was like six of us all around the tank and we're all like, not just watching the octopus. Our hands are in the tank and the octopus. And then we thought, oh, you know what, let's get another fish and we look in like, where's the bucket? Do the bucket? No, no, no, the bucket. She had stolen the bucket of fish right from under, literally under our noses. That's how smart they are.

CURWOOD: It's amazing. Such a hugely intelligent, sentient animal that looks nothing like the rest of us.

MONTGOMERY: No, we last shared a common ancestor half a billion years ago, when everybody was a tube.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery’s new book is The Hawk’s Way. Thanks Sy! Im looking forward to your next one.

MONTGOMERY: Great, thank you, Steve.

[APPLAUSE]

Links

Find out more on “The Hawk’s Way” on the Simon and Schuster page

Find the book "The Hawk’s Way" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth