Imagining Wolves Returning to Scotland

Air Date: Week of July 30, 2021

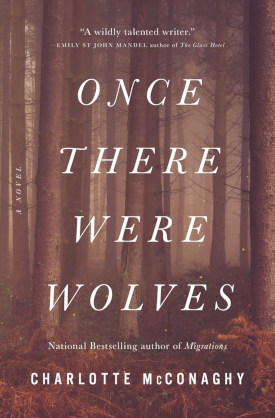

Once There Were Wolves is a novel about a woman working to reintroduce wolves to the Scottish Highlands. (Photo: Mark Kent, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Charlotte McConaghy is the author of last year’s best-selling novel Migrations. She joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about her newest book Once There Were Wolves, a mysterious tale of a woman-led team working to re-introduce wolves to the Scottish Highlands, the people who confront them and the deadly toll of domestic abuse.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[WOLF CALLS SFX]

CURWOOD: Wolves have captured our collective imaginations for thousands of years.

[WOLF CALLS SFX]

CURWOOD: The founding of Rome, for example, starts the legend that two brothers, Romulus and Remus, were raised by wolves. Once common throughout North America and Eurasia, today wolves live on just a fraction of their former territory. And that inspired Charlotte McConaghy, author of the international bestselling novel Migrations, to spin a captivating yarn about a woman working to reintroduce wolves to the Scottish Highlands. The novel is called Once There Were Wolves. Charlotte joins me now from Sydney, Australia. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

MCCONAGHY: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: So, the main character of your novel, her name is Inti Flynn, has the task of reintroducing wolves to the Scottish Highlands. And she says, or rather I should say you have her say, that she's always loved wolves without reason. But Charlotte McConaghy, if you had to give a reason, what inspired you to write about wolves?

MCCONAGHY: Well, I didn't know a great deal about wolves before I started this project. My knowledge kind of came from fairy tales as a child, which kind of vilifies them. So I always thought they were magical and beautiful and scary, I suppose. But I started to learn more about them when I first read an article about Pando, the trembling giant, which is the oldest and largest living organism in the world. It's a forest of quaking aspen trees in Utah, which are all connected to the one enormous root system under the ground. And this beautiful kind of ancient thing that's been here, some scientists think it could be almost a million years, is starting to die because of human impact. And at the bottom of this article, it says the perfect solution to saving this organism would be to reintroduce wolves back into the area, because they have incredible power over their environment. But that also, this would never happen because of the local farming and hunting community. And I kind of instantly had this story in my mind, it came to me very quickly in a huge rush, that I wanted to write the story of the woman who was trying to bring these creatures back in order to save a forest, much to the kind of horror of the local community. And so I started to look into wolves and discovered that they're the most extraordinary creatures.

Once There Were Wolves is Charlotte McConaghy’s sophomore novel, following last year’s Migrations (Image Courtesy of Charlotte McConaghy)

CURWOOD: Reintroducing wolves would protect these ancient trees, and they are quite glorious, as you say, these quaking aspens. And you have rather extensive but very accessible ecology lessons in this novel. So just explained to us, to someone who might not say instinctively, why would wolves help protect trees or a whole environment? What's going on there?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, so I think in simple terms, ecosystems need predators, because the predators keep the herbivore populations in check. You know, there's problems all over the world with way too many deer just running rampant, and eating all the little shoots and plants and stopping anything from growing. So when you get wolves back into an environment where they should be, they get the deer moving, which allows the plant life to grow. And it encourages all kinds of other mammals and insects and birds to return to a space. I mean, it changes water tables. They can actually, that's why we say that wolves have the power to change rivers.

CURWOOD: That's just so fascinating. The power to change rivers.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah.

CURWOOD: So you place this in Scotland, which, if I have my history right, I mean, they got rid of wolves in England, and then in Scotland, I don't know, 500 years ago. I mean, they've been gone for a long, long time.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's right. Yeah. Like anywhere in the world. They set out to destroy the creatures they thought were dangerous. But in fact, they're not. I mean, not to humans.

CURWOOD: You say, wait, wolves aren't dangerous to humans?

MCCONAGHY: No, I think I know, I think it's, we all tend to think of them this way. But that was one of the kind of amazing things that I learned during my research is, in fact, they're incredibly shy, family oriented creatures who are terrified of humans, and they will go out of their way to avoid all human contact. The instances of wolves, attacking or killing humans are so minuscule, it's sort of, it's not even really worth talking about. I mean, deer kill more humans.

Wolves' society is matriarchal, with breeding females holding the most power in wolf packs. (Photo: Ralph, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: You mean running in front of their cars?

MCCONAGHY: That's right.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but the Scottish community that you place your story in, is like many others, they're not so inspired by wolves in your book. They're afraid of them. How does the wolf inspire so many and scare others?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, it's interesting. That is one of the things that I kind of found so fascinating was this ability they have to, I guess, conjure these extreme feelings in people. You have both ends of the spectrum. They sort of generate a lot of fear. They also generate a lot of love. And people are very passionate about wolves. And I think maybe it's because they sort of reflect our ideas of the purest sense of wildness in a way. I mean, Barry Lopez, who was an amazing nature writer, wrote that wolves, we've projected onto the wolf the qualities we most despise and fear in ourselves. And I think that's very true. You know, and I sort of wanted to explore that idea in this book. And, and I guess, maybe flip the idea that the wolves are the monsters and kind of say that it's us. We're the monsters.

CURWOOD: Of course your book isn't just about wolves. It's about people, inspiring parts of people. And then the dark side, there's a fair amount of domestic violence in this story. Charlotte, what does this theme mean for your book?

MCCONAGHY: I mean, this was one of the things I was grappling with. Initially, I was feeling very angry about the slaughter of wolves. But I was also feeling very angry at, we've got a domestic violence emergency going on, I know, in my country, and I think all around the world. A woman a week is murdered by her romantic partner in Australia. And that's not including all the women who are not, you know, survive their ongoing abuse. I was writing this novel from a very angry place. And so Inti, in a sense, kind of became the mouthpiece for that fury about the way that humans treat, not just the natural world, but each other as well. She becomes someone who's very kind of acutely aware of the damage that people can do to each other sort of part of the way she comes to see the world. She's lost all faith in people. And the book is kind of about a journey, I suppose from about laying that anger down or finding a way to move on from it, rather than letting it kind of poison you.

CURWOOD: By the way, did that work for you? By dealing with it in such intense and intimate and, frankly, graphic ways? Has it helped you?

Despite appearing threatening, wolves are relatively harmless to humans. In fact death by deer, Charlotte McConaghy says, is far more common than death by wolf. (Photo: Tambako, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

MCCONAGHY: Well, it's still an issue that really, I'm very passionate about. And it's very upsetting still, because we haven't solved this issue. And I don't think this is a book about forgiveness, a lot of things shouldn't be forgiven. And this is one of them. But I suppose, yeah, rising Inti into a place of healing was, it was healing for me as well, in a way.

CURWOOD: Talk to me more about wolves. What is it that you came to really appreciate and understand, and I don't know, if you've got to the point of even revering wolves, some might say that this book certainly holds them way up there. And then what maybe did you discover you didn't like so much?

MCCONAGHY: Okay, um, I think what I was most surprised and fascinated by when I was doing my research was the incredible uniqueness of their personalities. They have extraordinary kind of distinct, mysterious behavior, that is very hard for us to as humans to perceive and understand. In a way, they're sort of really human in their behavior. But in another way, they're kind of really unknowable. And so I think I just fell in love with this uniqueness. You know, each of them have their own kind of lives and adventures and stories and personalities. And, you know, you only just have to follow one to fall in love with it and kind of see that they have this amazing sort of sense of loyalty to each other, courage. I mean, there's a part in the novel, which I kind of took inspiration from a real wolf in Yellowstone, when she loses her mate she howls for him endlessly, which is her method of mourning. And that just felt so kind of, so human in a way, but also so animal. And I think there's something that we can really learn from wolves about the way they love.

CURWOOD: I mean, you right towards the end of your story, there was a quote, when you open your heart to rewilding a landscape, the truth is, you're opening your heart to rewilding yourself, what's happening here?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think it's like I've said it's the idea of reconnecting, rebalancing, finding a sense of harmony with wild spaces and places and with the wildness that exists within us, instead of, I guess, separating ourselves to the detriment of everything.

CURWOOD: What do you make of the general understanding now that a wolf pack wolf society is matriarchal, that the alpha alpha wolf is the female wolf, the Mother Superior, whatever you want to call her for the pack? And the strongest male, the alpha male, you know, comes in and out but doesn't run things the way she does?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, well, I guess it comes down, we call them, they're called now the breeding pair. So instead of the alpha male and female, it's the breeding male and the breeding females. So, and I think that they come to that dominance because they breed rather than because they're sort of more violent or kind of controlling than the other animals, which is sort of fascinating in itself. And I think it really flips that idea of what wolves are on its head and kind of says, Well, no, actually, the thing that they value most or the most powerful part of their society is nurturing and bringing pack into the foreground, raising pups.

Author Charlotte McConaghy lives in Sydney, Australia (Photo: Emma Daniels)

CURWOOD: Scientists who study wolves are careful not to name them. In fact, one of the most famous breeding pairs of wolves are just simply known by their numbers, Wolf 21. And Wolf 42. The Lamar Valley, they're at Yellowstone, the wolves who died not too far apart in time because they were so attached to each other. And almost all of your wolves don't have any names except for one. What, what prompted you to say, well, you know, what the heck I need to name this wolf?

MCCONAGHY: Well, yeah, I was, I found the same thing interesting about scientists not naming their wolves. And it makes sense. I mean, apart from, you know, the need to be scientifically accurate, I think there must also be some element of perhaps not wanting to get too close to these wolves, because what you're seeing as a wolf biologist is the upsetting reality that wolves don't live too long. You know, there's a lot of things that are dangerous for a wolf in the world, and a lot of ways for them to die. And so I think, I mean, at least for my characters, there's a sense that getting too close to them is making themselves too vulnerable to the loss of these wolves. And that's why they don't name them. But there's this one in particular, that Inti becomes quite enamored with. And I think she sees a little bit of herself in this wolf in some ways. And that's why I think even against her better judgment, and against her will, she starts thinking of this wolf with a name. And I think that was just my way to, I guess, indicate that Inti was getting too close. We're getting closer, than she knows she should.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think wolves might actually be brought to the Scottish Highlands after all these centuries? I mean, the way you write this makes it sound like it just could happen the way it is in this book. Tell me more about that. How likely is that to happen?

MCCONAGHY: Oh, I would like to say it's more likely than it is. It's a big topic for discussion over there. It's a big debate that's going on, conservationists can see the benefits and the impact that it would have on the environment. And you know, Scotland is a very progressive country in terms of its rewilding efforts. So it's I don't think it's impossible. But there's also a very big pushback against it from the farming population, because it's very densely farmed. And there's a lot less land, you know, than there is in America, for example,

CURWOOD: It wasn't exactly easy to get wolves reintroduced in the lower 48, here. There was huge pushback in that effort. And yet, I guess today, it's safe to say that it's going reasonably well. Why do you think it worked in Yellowstone?

MCCONAGHY: I think it worked because wolves are meant to be there. They used to be there and they should have never left. Essentially, it worked because nature intended it.

CURWOOD: Charlotte McConaghy is the author of the novel Once There Were Wolves. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MCCONAGHY: Thank you so much for having me back. It was lovely to chat.

Links

Living on Earth’s interview with Charlotte McConaghy about her last book, Migrations

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth