Sexual Misconduct in the US Forest Service: One Woman’s Story

Air Date: Week of March 16, 2018

Abby Bolt has been in the U.S. Forest Service for 21 years. (Photo: courtesy of Abby Bolt)

Abby Bolt loves her job as a Battalion Chief for the U.S. Forest Service, leading forest fire prevention efforts and commanding teams of hundreds of people in a disaster. But in a conversation with Host Steve Curwood, Bolt describes a “good ol’ boy” culture in the agency that casts a blind eye over sexual misconduct, hazing and harassment directed at the few women in the agency. Bolt says instead of addressing complaints, some supervisors in the Forest Service protect the harassers – even punishing women who speak up.

Transcript

CURWOOD: In 2016 we ran a story about sexual misconduct and harassment in the agencies that manage US public lands. Women spoke of assault and intimidation in the National Park Service and the US Forest Service where firefighters are overwhelmingly male. There was talk of change, and some, but not much, action in response to the complaints.

Well, since then the “me too” movement has brought to light the widespread incidence of such misconduct. US Forest Service Chief Tony Tooke recently resigned amid allegations of sexual wrongdoing. He quit just a few days after PBS Newshour ran special segments about abuse and harassment in the agency, focusing on some of the women who have filed complaints and suits. Today, we bring you the story of one of those women in the Forest Service. Abby Bolt is a battalion chief in the firefighting division based at Sequoia National Forest. Welcome to Living on Earth, Abby.

BOLT: Hi, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, first tell me about your job. I understand that you've been with the Forest Service for a number of years.

BOLT: Yeah, I cannot believe that I'm into my 21st year of fighting fire. I just started doing it to put myself through college and do it in the summers and then next thing you know, I became what they call a "lifer" and took the full-time job. And now it's been over 20 years. I started off with hotshots and was a helicopter rappeller, and then went into hand crews and engines and now I actually specialize in fire prevention and public education.

CURWOOD: Hot shots, I mean, helicopter rappelling sounds like either jumping out of planes or climbing out of aircraft right into places that are on fire. Why do you do that? Why do you want to do that?

BOLT: Ahh, those were the highlights of my career. Why do I want to do it? I mean, I grew up in the outdoors. I love to play sports. I love to be athletic and competitive, and you know, it's hard to be on a professional ball team. So, the next best thing was being on a team to fight fire, and there was just so much satisfaction to it that it's addicting. You know, even the worst days, the most miserable days where you're just trudging along in the ash just doing the same menial work looking for little hot rocks all day long, even those days are really memorable and great.

Earlier in her U.S. Forest Service career, Abby Bolt worked as a hotshot firefighter. Above, a crew of hotshots tackles the Cedar Fire in the Sequoia National Forest, August 23, 2016. (Photo: Lance Cheung / USDA, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: What kinds of behavior have you noticed over the 22 or so years that you've been working with the US Forest Service?

BOLT: There's a great camaraderie, there's really great teamwork and there's really great friendships, but then and along with that can come the hazing and some of that behavior that probably isn't acceptable, but when you're brand new you don't really realize it. So, my first years I dealt with … I dealt with things like porn being taped to my buggy seat. The person that sat behind me used to flick his ashes into my hair and I didn't know it until it was melting my hair and people told me about it, but that would happen days on end, and you might pick up your backpack and it's full of rocks or maybe a dead animal in it or there might be you know, something silly and I don't know that...I think it just has to do with being the odd man out, you're the new person. I was the first girl on a crew who hadn't had a woman in a long time and they just they didn't really know any better, I think, and I just wanted to be there. I was so in love with the job and just that first year my goal was to never ever let them make me cry, and I never did. So, that kind of thing, you'd open up your pack, toss the things out, keep moving.

CURWOOD: So, in that first year did you say anything to your supervisors or or anybody about the harrassment, you know porn being left on your truck seat isn't exactly ordinary hazing.

BOLT: I did, because I didn't want to be the only girl they had in a long time and then instantly be a problem. So, I tried to defuse a lot of it on my own and blow a lot of it off, and then there was one particular guy that just would not stop. He wouldn't stop picking at me and I remember it would make me so angry, he would either, you know, physically shove me or touch me or throw things at me or basically dump all of his work on to me. He would drop things at my feet that he was supposed to be carrying, just little silly schoolyard things and I just got so frustrated, that and all of that other stuff happening on the side.

I finally went to my supervisor at that time and just said, “hey I need your help ... can you just help me deal with this guy.” I wasn't complaining, I just said I needed to deal with him for me and he just simply said “Hey, Abby, you're on your own.” And I said, “Well, on my own, I'm getting so frustrated I'm going to end up smacking this guy with my tool at some point to get him to back off,” and he said, “Well you do what you need to do.” And that day kind of came there was a day where I finally he did something to me out in the middle of a fire and I remember I was so mad and couldn't get him to back off and I did smack him with my tool to get him to back off. That's just kind of that you take care of yourself, and that's what I was told. And towards the end of the season, when we were doing our exit interviews, I told all of the supervisors on the crew, I said, “Hey, just just know that this was going on and that I'm not going to complain because I love this job, but I just want you guys to know so you watch out for it in the future,” and I would like to say to think that they took that forward and did something good with it, but I was actually pretty much blackballed for a long time because I said that.

While managing a forest fire as a Battalion Chief, Ms. Bolt oversees a chain of command that can include 300 to 500 personnel. (Photo: courtesy of Abby Bolt)

CURWOOD: And their solution was violence. Hey, these guys are hassling you, then do whatever you need to do to take them out. Almost an explicit order to you to do something physical.

BOLT: Right, and it was. And at that point in my life, I mean, I didn't even know about things like EEO or formal reports, and I don't think I ever even filed one of that point, and what ended up happening is the guys that were on the crew that believed in me, they rallied around me like brothers and ended up sticking up for me and they – they handled that guy in the end. So, they did.

CURWOOD: But you were blackballed.

BOLT: Yeah, I was.

What did that mean?

BOLT: I didn't realize how bad it because I performed well and I did a good job and I went on to do great things and continued there and then became a rappeller, but one of the supervisors, the one that I asked for help and told me to deal with it on my own, years later I actually got a job offer somewhere on another hot shot crew and he went out of his way to make a phone call to tell them that they shouldn't hire me, and he had no reason to do that, no reason at all except for I did stand up and say, hey, you guys could have some problems with women on this crew if you're not careful. I just gave them a fair warning and years later, he made sure to ruin a job for me.

CURWOOD: So, they didn't hire you on that crew.

BOLT: It was even after they had made the official offer and then they rescinded after he reached out. That's a piece of that good old boy stuff that goes on and it can follow you in fire and and burn you for the rest of your career, and that's why people stay quiet.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me what happened to you back in 2012. You went on assignment in Colorado.

BOLT: Yeah, I was actually in Wyoming and Colorado and I was with an incident management team, and we were traveling around the country, had a few fires that we were dealing with and one was in Wyoming, and then also we were partly in Colorado. And towards the end of the assignment I was sexually assaulted and raped by another firefighter that wasn't a member of our team, but he was there working with them and it was a violent situation by somebody that I was an acquaintance with and I never understood like how that could happen or what you do in that situation. and I just I remember negotiating with him and pleading with him, and long story short I was covered in bruises and, yeah, so...

CURWOOD: I'm so sorry. It's just so horrible.

BOLT: Yeah, it's just one of those situations you find yourself in and it's surreal, like it's not happening to you, you're just watching a TV show in your head that must be all that it is, and the next day it was time for me to drive home back to California and I just ... I was in shock, literally in shock and shame and I didn't know what to do. Like I knew that it was wrong and I knew that I needed to do something about it and report it, but then all the thoughts in your mind of what's going to happen to you in the agency and in the fire service, what will rip your career apart. You know, when I show up to a fire, I show up and people look at me and go “There's Abby, that's that division supervisor we had on that fire where we saved all those homes.” And after you report something like this you show up to a fire and now “There's Abby, she's that gal that was in that rape trial that ruined that firefighter's life.” It becomes your identity, and we had a team of like 56 people there, and once I reported it, an investigation would have shot through the roof. Everybody...that whole team would have been stood down for fire assignments and they would have been questioned and it would have brought so much darkness to so many good people. I didn't want everybody else to have to pay for what I went through.

Ms. Bolt and two other U.S. Forest Service fire officials consult maps while commanding a firefighting operation in California. (Photo: courtesy of Abby Bolt)

So, on my way home driving back to California, my best friend ever since we were little is with the police department here and I reached out to her just in tears and I told her I didn't know what to do, and of course she was pleading with me to report it and told me that I had to, and I explained to her all the reasons and she know how it works in her department, what it would feel like for her. And because imagine the investigation, it's not just a police investigation. We're talking federal, all the agencies, it would have been a mess in different states, and I've seen how our agency doesn't do very well on things that are much less than that. How would they have treated that? How would they have treated me? How could I have trusted them? So I told her and she convinced me to come down and at least do the police report. And I met with the SVU detective and we went through all of it, and I went to the hospital and I did the rape kit to make sure that all the evidence was captured. But I just – I couldn't bring myself to actually tell the agency because I just … I knew it would ruin everything, and it would be easier if I could if I just kept moving forward.

CURWOOD: So you got the rape kit from the local police department where you were assaulted or back home or?

BOLT: Actually, back home where I live, and they ended up working with the police department where I was assaulted, and both of those detectives kept following up with me and they were pleading with me to press charges, and I just couldn't bring myself to do it. It was in the middle of the fire season. I was still traveling around fighting fire, and I just – I wanted to be known in the agency for my firefighting abilities not for that. Of course, now that's changed, but they kept telling me you've got to do something or this will happen again or maybe he's doing this to other women or ... you know and I was thinking about his family and his children that I knew that he had and I didn't want to ruin anybody else's life, but I instead of confiding and letting the police protect me or going through the judicial system which I just didn't trust at the time, I confided in a – in a friend on a hot shot crew that I was really good friends with and I knew that he knew my assaulter, or I knew that he knew who he was because they both lived in Arizona. He told me, “Abby don't worry we will watch out for you and you give us the word and we will take care of him and we will keep him away from you.” It's a bunch of brothers in this job, it's a bunch of big brothers that are just amazing and like their little sister, they made sure that I was protected and we would go to fires and if he would be around, they would - they would eat their meals with me, they would just keep an eye on me, and they did put him in check couple of times, and had to pull him aside and so they were my justice. It ended up being kind of a brotherly justice that I had and it felt like at least that was something that I did have to protect myself and not let that man know that it was known about and he was put in check. But then in 2013 that friend of mine and his entire crew except for one of them, they all died in a fire.

CURWOOD: They all died in a fire.

BOLT: Yeah. So, they all died in a fire in 2013, and I think I was just devastated from that already, but then that was my justice, and I also lost my justice and my answer to how I responded to the assault. So, that tore me up pretty bad.

Abby Bolt, left, with Jesse Steed,

who was the friend and colleague in whom Ms. Bolt confided about her 2012 sexual assault. Tragically, in 2013, Steed and his entire Granite Mountain Hotshots crew, except for one team member who was at a different location, perished when they were overrun by the Yarnell Hill wildfire in Arizona. (Photo: courtesy of Abby Bolt)

CURWOOD: One of the things that so awful about sexual assault is obviously, how people ... what happens to your life afterwards. How are you doing in the aftermath of this? It's just such a devastating thing.

BOLT: Yeah, I'm still trying to figure it out actually. I'm still trying to figure that out. And I think I buried a lot of it, and this is all definitely pulling it forward. I didn't tell my family. I told, you know, I was married at the time and he knew, and you know we -- he helped me through it, and but it was really hard on us. But I didn't tell my mom and my dad because, one, I was afraid my dad might just lose it and go out and take care of his daughter. But I just, I didn't want that weighing on their hearts, you know, so I kept it inside and just worked with the police and then worked with those friends of mine that were watching out for me and I buried it and that's definitely affected me though. The fact that it all happened isn't what gets me so much right now and why I've come forward about it. The fact that that I knew that I wouldn't be able to trust in the agency to take care of me if I reported it.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the kinds of bullying that you have experienced since that incident.

BOLT: The bullying that I've dealt with since then, it wasn't – didn't have anything to do with that incident because I hid that from my agency in general. So, since then it's been like ever since I would speak up for either myself or for other employees that weren't being treated well, I've just been completely burned for that. But it all seemed to happen when I went under the supervision of a particular supervisor because for 18 years before that, maybe I had worked for somebody difficult, but I never had these problems. And I'm dealing with all that with in a complaint now and I've tried, the thing that kills me is I tried from the lowest level because that's how we're taught, try to fix things at the lowest level. If that doesn't work, go to the next level, and then the next level. And I just was banging my head against the wall with the lowest level trying and trying and trying, and then the next level. But what happens is you bring something to the attention of your supervisor and if his supervisor wants to protect him he absolutely will.

Despite the hazing and harassment Ms. Bolt says she experienced during her first year firefighting with the Forest Service, she says, “That goal my first year was to never ever let them make me cry. And I never did.” (Photo: courtesy of Abby Bolt)

I would speak out about something that was so blatant, but then it was almost like his supervisor didn't want that sort of a thing to come out, and they start covering up for each other because then if the word gets out that there is a hostile work environment or some sort of poor treatment happening on their unit, that's going to get out further and further and that's not going to look good. So, I think that motivates them to cover up for each other, and then they start making the person that is making a complaint look like the problem because it's a lot easier if you get rid of that problem than if you admit that there's actually a problem on your unit or a problem with one of your leaders.

CURWOOD: What kind of litigation, if any, are you engaged in now against the department given this devastating history?

BOLT: Well, you know t's been ... 2014, I finally had to step forward and file a complaint and that fire season kind of ate that up. There's really no employee advocates out there that are truly on the employee's side, so it's really tough when you file a complaint to know what your deadlines are and really understand all of that and have an advocate because you also are expected to do your regular job. There's a lot of time that has to be spent on that, but if you're the agency that you're filing a complaint against, they have endless resources to help them. So, that moved on and I basically just had to let things go because I needed to get on with the season and being a supervisor, but then the retaliation started.

There were a lot of opportunities taken away. I used to teach at academies and I'm talking about big fire academies that were very respected. They wouldn't let me teach any more. I was on committees. They took me off of all of the committees that I was on. There are a lot of opportunities that are critical for your career and your advancement and your networking, they were just slowly taking all of those away. They made me move my office miles away from where it was, just me but not the other male that worked there that was in the same position. So, then I made the phone call and started the retaliation complaint. So, that was in 2015. And then one thing after another where they're just not being responded to. I'd reach out to our civil rights folks and tell them literally what was happening in my office and I would literally write e-mails that said, “Please help me,” as blatant as I could so that they would maybe read them and they would say maybe we should check in on her and see what's going on, and they would get ignored for for a long time.

CURWOOD: Outside of official actions that feel like retaliation, to what extent have you felt threatened, intimidated, by things that you're not sure of the source of, but nonetheless for you, well, frankly downright creepy?

BOLT: That's what starting to eat me up and, you know, the supervisor that I was working for and he's moved on, he would make very odd comments and it was getting creepy, and then it was actually just a one sentence note that was typed up and addressed to me in my inbox and said that that I was a prime example of why women didn't belong in fire, especially single mothers. And then my – the back of my car window was written in, just the word "quit" and I had heard that one of my supervisors had been saying that and he had also said it to me in passing. So, it just makes you not even want to enter the building, and I go to bully meetings at my child's school, bullying prevention meetings and we're talking about how to keep kids safe on the playground and in the classroom, and I sat there one day and realized like, oh my gosh this is verbatim what is happening in my workspace. You know, it's schoolyard bullying at an adult level.

CURWOOD: Firefighting is a dangerous business and I'm sure you've been in many situations where you really needed to make sure that the people you were with were going to literally have your back. To what extent did you feel that the harassers, the bulliers didn't in those circumstances?

BOLT: There was – there was a time in the very beginning where that happened a few times. There was, you know, I had had fire literally lit underneath me, just because they thought it would be funny and they left me there. I’d had rocks rolled from the top of a hill down towards me, which have killed people. There's that kind of thing. So, yeah, you kind of lose that sense of safety because if they're not going to be good to you in the buggy, they're not going to be good to you out on the fire line.

Forest fires are becoming more intense, and fire seasons longer, as climate change warms and dries out trees throughout the West. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Now, that I'm further in my career and I'm in more of a leadership position, I even told our four supervisor this in writing and in person several times about the hostile work environment and the hazardous human behavior that was happening underneath him with a couple of our fire leaders, and I told him that eventually this kind of behavior is going to bleed over to a fire and the behaviors that they're displaying in the office were going to come out on the side of that mountain in the fire because maybe – maybe they don't answer the radio when they should just to be mean or maybe they don't fill an order when they should or call that helicopter when they should just because they're retaliating and eventually it's going to get somebody killed.

CURWOOD: Abby, what gives you strength to go through this? What's helping you get through all of this?

BOLT: Well, my family. If I didn't have my family, you know, I've got really strong sisters and my mom for women, and my parents always taught me to speak up if you see something wrong, say something, do something about it. And it's so much easier for me to speak up and protect somebody that isn't me. I'm much more comfortable speaking out for someone else, and it's been really hard for me to speak out for myself, and my significant other, he's been amazing. He's also with the agency and so supportive and he admits he had no idea how bad it could be until he saw it from my eyes and saw it from the inside, and if it weren't for the folks that love me, I don't know what I would do right now, and there's so many gals in fire, and just the e-mails and the phone calls and the messages I've gotten since I came out on PBS, like, there will be another one that will come in that will confess to me the pain that she's been in what she's dealt with and she's thanking me for speaking out because she can't because she's scared, and I'll get one of those and I think, “Now that is the reason I did this. That's the reason I'm speaking out.” And then I'll get another one and I think, “That's the reason,” and quite honestly, there's ... still when I go into a classroom to teach about fire prevention, there will be little girls that walk up to me still and they say like, “I didn't know that girls can do this, and it breaks my heart. I'm like, “You guys, it's 2018, what do you mean you didn't know little girls could do this? You can be anything you want to be.” And I realize that anything that I do now to help bring progression is going to help some little girl some day that I'm never going to meet. If I lose everything right now, but it is going to make things a little bit better then, I'm good with that because that's how strongly I stand behind this.

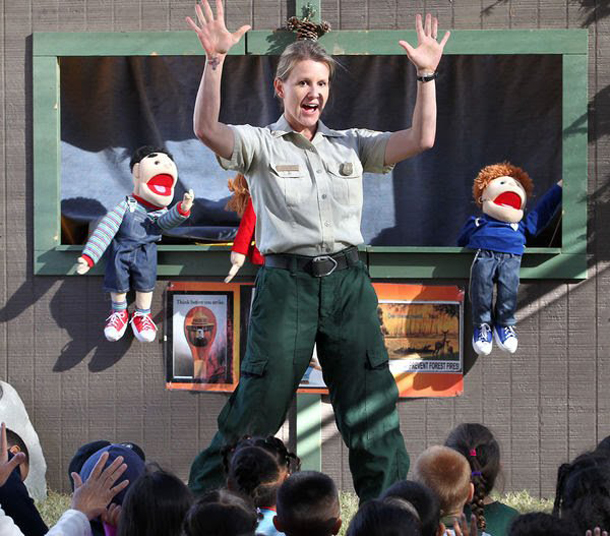

As a Battalion Chief, Abby Bolt teaches kids and the public about forest fire prevention. (Photo: Casey Christy / Bakersfield Californian News Paper)

CURWOOD: Abby Bolt is a battalion chief with the US Forest Service Fire Fighting division. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BOLT: Thank you for having me. It's been a really a pleasure and thank you for the work that you guys do.

CURWOOD: There’s more on this topic at our website – loe dot org. It includes the story of a young woman who thought working for the US Forest Service was just the job she wanted.

MYERS: I got what I thought was a dream job, fighting wildland fires. You know I was gonna get paid to go hike out to fires and camp and it was gonna be really exciting.

CURWOOD: But sexual harassment and bullying quickly turned that dream into a nightmare. To hear her story, and for more about the challenges women face protecting public lands, go to our website loe dot org. And share your thoughts and experiences, if you like. Write to comments at loe dot org. That’s comments at loe dot org.

The U.S. Forest Service declined to comment on specific cases, citing privacy, but in an email to PBS NewsHour said it takes “all reports of sexual harassment very seriously.” The link to the Forest Service's Anti-Harassment Policy is below.

Links

Our 2016 LOE story: “Sexual Harassment Blights National Parks and Forests”

U.S. Forest Service Anti-Harassment Policy

PBS NewsHour: “They reported sexual harassment. Then the retaliation began”

The Washington Post: “Interim Forest Service chief named amid misconduct charges”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth