The End of Epidemics

Air Date: Week of February 16, 2018

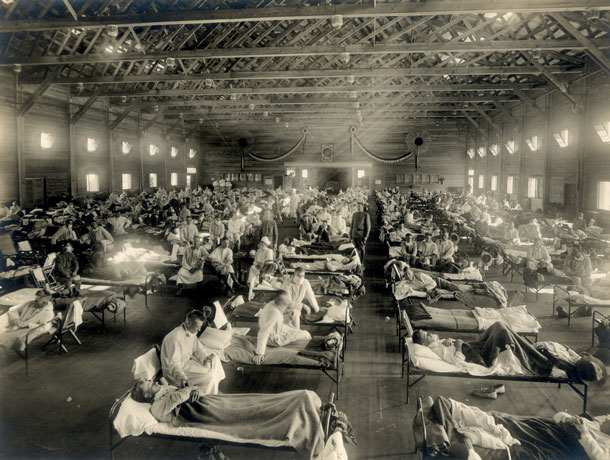

An emergency hospital at Camp Funston, Kansas where nurses and doctors tended to those infected with the 1918 Spanish Flu. The pandemic killed between 50-100 million people globally. (Photo: Otis Historical Archives Nat'l Museum of Health & Medicine - NCP 1603, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Since a deadly influenza pandemic killed as many as 100 million people a century ago, medicine has come a long way, but we still have no truly effective vaccines against the seasonal flu which is proving serious this year. Host Steve Curwood discusses the shortfalls of our current approach to this disease with Harvard Medical School physician, Jonathan Quick. His new book, The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It, focuses on containing outbreaks, and the need for a universal flu vaccine to control and prevent the next pandemic.

Transcript

CURWOOD: South Indian frogs may prove key to making a better flu vaccine, but it won’t help us with this season’s particularly nasty outbreak. Influenza is widespread in 48 states and is proving to be particularly deadly, with 4,000 related deaths in just one week in January. Thankfully this year is not as bad as the so-called Spanish Flu pandemic at the end of World War One that sickened a third of the world’s population and killed perhaps as many as 100 million people. And despite advances in medicine since then, we are still far from safely containing the next major pandemic. That’s according to global health physician, Jonathan Quick, who calls this challenging flu season ‘a teachable moment.’ In his new book, The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It, Dr. Quick offers a road map for local, national and international actions that could prevent killer outbreaks in the future. He teaches at Harvard Medical School and joins us now - welcome to Living on Earth!

QUICK: Thank you. Good to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, tell me, how bad is this year's flu so far and why?

QUICK: Well it certainly is racking up a higher case count. There are two things that are different about this flu. One is that the mix of strains of flu that actually hit the US were different than what were predicted months ago when the vaccine was made. So, we're only getting at best a 30 percent success rate with the vaccine. The second thing is this is a particularly vicious strain of the H3N2, which -- it causes a reaction in the immune system such that you can get a really rapid and catastrophic death. It's the sort of characteristics of the virus that we had in the 1918 and the 2009.

CURWOOD: And when you talk about 1918, the so-called Spanish Flu, killed how many people?

QUICK: Between 50 and 100 million; more recently the estimates have been on the higher side.

CURWOOD: What is it about our typical flu response that isn't working in your view?

QUICK: Well, one of the big things is that the flu vaccine is one of the least consistent of the vaccines we have because it's made each year based on the best scientific guesses of what particular strains of flu will hit us. And if we're right we get 60 percent effectiveness at the best, and if we're wrong, we've gotten as little as 10 percent. We really need a much, much better flu vaccine.

CURWOOD: Now, you say that our collective flu complacency is actually what's killing us. What do you mean by that?

QUICK: Well, that what happens is when we have a bad flu season, there's this sort of panic and a lot of activity - how do we take care of ourselves, what about our children? - but then once that season goes and it's off the headlines - kids are back to school and businesses are going again - we fall into a complacency. We just get focused on other things.

CURWOOD: What's likely to be the economic impact of a rough flu season like we're having this year in America?

A U.S. marine receives the influenza vaccine. This year’s H3N2 flu virus, like the strain of the flu that proved so deadly in 1918, is highly contagious and killing numbers of young healthy people and children. (Photo: U.S. Pacific fleet, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

QUICK: Well, we know on average from work done by the Centers for Disease Control that the average flu hits the US economy at over $80 billion dollars a year of which about $10 billion are the health costs. So, this year we can expect that the total will go beyond that, when you consider lost time and all of the other factors.

CURWOOD: And how many people - I know this is kind of grim - but how many people do you think will perish in the course of this? Or are likely to?

QUICK: Well, the highest that we've seen is 56,000. I wouldn't be prepared at this point to predict, but that would be near the top end of what one might expect.

CURWOOD: 56,000 people! I mean that's more people than who die in car crashes every year!

QUICK: Yes, it is, and that's really unacceptable to be in a situation where we have a vaccine that really won't protect us, and when we see that kind of a death rate. And if we had what we had in 1918, which we could have again, which is a flu that is both highly deadly and highly contagious, we could be talking about multiples of that.

CURWOOD: So, what's the fix to the flu vaccine problem? You say at best it’s 60 percent effective.

QUICK: So, if you think of the flu virus as a mushroom, and the top of the mushroom is the part that is easiest to make the vaccine to, and that's what we've been doing, but that's the part to keep changing all the time. And the stem, which is the least changing and the most stable, that's what we really need to have a vaccine for. So, the universal flu vaccine is meant to either get a wide range of strains of flu or to get that stem so that we don't have to keep getting a flu shot every year, and so what we need to do is to move along, accelerate research on the universal flu vaccine. And Professor Osterholm from the University of Minnesota has said - and he said this five years ago - we need to put a billion dollars a year into getting a universal flu vaccine. Which is a fraction of what the influenza cost this country alone. If we get a good flu vaccine, universal flu vaccine, it would be good for the entire world.

CURWOOD: So, how does complacency figure into this really high death rate? I mean, this is the 21st century. You’d think that we would have had this handled by now.

QUICK: Yes, and here's the thing. We have the scientific know-how and the public health community knows what to do, but we need to... first of all, we need to invest in making sure that we have the best public health information in communities. The fact is that basic good public health, personal prevention is actually highly effective, more effective this year than the vaccine as it turns out.

CURWOOD: Well, and what are those public health things that people are doing that are so effective?

QUICK: Well, simple things. It's proper handwashing, not just sort of wet and dab, but a good 20 seconds, two verses of Happy Birthday, with good soap and all over. It really makes a difference. The second thing is safe sneezing and coughing. Covering your sneeze and cough, but not with your hands where you're going to wipe it on surfaces, but into your sleeve, and the third thing is stay home from work. Stay home whether it's work or school when you do have the flu and don't be macho about it. People at work or school won't appreciate that.

CURWOOD: One thing that's attracted people's attention this time is surprise at seeing young people, you know, 20-year-olds, 30-year-olds, because some people have the attitude the flu just sort of shuffles the nursing home population.

A health worker wore protective gear during the Ebola crisis that took hold in West Africa in 2014. (Photo: USAID, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

QUICK: One of the basic misconceptions is that if you're young and healthy, you don't need to worry about it. The problem is if you are somebody that’s susceptible to some of the complications of influenza, it doesn't matter how young you are, how healthy you are. If that flu virus stimulates this reaction in your body where your immune system starts fighting with itself, it doesn't matter how fit you are. And when that particular kind of a reaction happens, that's when we see young, otherwise healthy people die.

CURWOOD: So, how does someone know if their immune system can be thrown into a tailspin?

QUICK: Well, you don't. Now, we know the dynamic, it's actually got a name. It's called a Cytokine storm. You can call it a C storm. It's got a lot of research on it, but we still don't know how to predict it, we don't know how to guess who's it going to be. So, when you hear these stories of people who have seemingly had the flu and have been seen and diagnosed and go home, and then, you know, are dead, it's a very good likelihood that they're one that was susceptible to that, and that C storm got going and basically put them into a respiratory failure. And that's why it is so important to get the vaccine. It may only cut your chance by 30 percent, but it's important to get the flu vaccine, but also if you are in the category of young and old for which the pneumonia vaccine is appropriate, that actually helps in preventing the bacteria complication of influenza, which is the other thing that will kill people.

CURWOOD: Now, you were talking about the flu because we're looking at this right now, but you wrote your book to sound the alarm that we could have an amazingly deadly epidemic that could really knock us back in horrible ways. Just how horrible a scenario are you projecting?

QUICK: Well, the most likely worst-case scenario would be this version of the flu, a pandemic flu, as in 1918, highly deadly, highly contagious, that spread around the world and there's a scenario that Bill Gates has supported that’s looked at what would happen. And in 100 days, we'd have about three-quarters of a million deaths. That would be like a bad year for the seasonal flu worldwide, in 100 days, three-quarters of a million. In 200 days, 30 million people, and it would hit every major population center. So, you get a cascade. What happens with the flu, you got the disease, sends people into the hospitals, and when you have people going into the hospitals that are at a rate more than they're equipped for, then that can quickly pull the health system into a crisis. You then, in workplaces, have suppliers, staff, customers affected by this and in this just-in-time economy of just-in-time inventory then you break down that system and so on down the line. And so it's that chain reaction that a really devastating epidemic would catalyze.

Jonathan Quick’s new book, The End of Epidemics: The Looming Threat to Humanity and How to Stop It, is both a call to action to develop a universal flu and a plea for all countries to develop preparedness plans for containing the next major disease outbreak. (Photo: Courtesy of St. Martin’s Press)

CURWOOD: So, what's to be done? To explore that question Dr. Quick, I want to ask you about another epidemic, Ebola. What did we do wrong after the Ebola epidemic broke out in West Africa?

QUICK: Well, let's put that epidemic in perspective. There have been 22 previous Ebola outbreaks in Africa since Ebola was first discovered several decades before. And every one of those came to an end with only a few hundred cases and even fewer deaths. So, what was different in West Africa was two or three things. First of all, the received wisdom was that there wasn't any Ebola in West Africa. In fact, German researchers had found Ebola there back in the 80s, so they should have been aware that it was a possibility. And so, the first thing is West Africa didn't really have the information it needed to protect itself.

The second thing is those three countries there have all been through decades of civil unrest of one kind or another. So, the basic ability to detect and rapidly respond to an outbreak wasn't there. Once it started to become apparent to the people on the ground and specifically MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières), Doctors Without Borders, they started ringing the alarm. One of my heroes from Ebola is Dr. Joanne Liu, the president of MSF worldwide, and she started in March of 2014 trying to ring the bell and say, “Look you've got a problem here, this is not normal”. And actually it was only when two international workers from the US were expatriated to Emory Hospital in the beginning of August 2014, within four or five days, the World Health Organization called the global emergency. So, there was a lack of information and then there was delay in responding and that's what let it really get embedded.

CURWOOD: So, what do you make of the World Health Organization ignoring the Médecins Sans Frontières, Doctors Without Borders, when they were sounding the alarm when it was still in Africa?

QUICK: Well, I think it was a combination of factors, which WHO has recognized, that they really need a faster system and a system that is de-politicized. So, when you mix the decisions to whether or not to act in a political context, the trade people don't want you to announce that you've got an epidemic, the tourist people don't, and so you've got to put it on a scientific basis. And I think to the credit of WHO leadership, they've said, “You know, this didn't go the way it should have,” and they've instituted a much stronger system, much more scientifically based and much more transparent.

Jonathan Quick is senior fellow at Management Sciences for Health in Boston and an instructor of medicine in the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School. (Photo: Courtesy of St. Martin’s Press)

CURWOOD: Now, to deal with these epidemics, you have a preparedness plan that you call the power of seven. Could you just please briefly describe those seven steps for us?

QUICK: Yes, the first is leadership that is courageous, decisive, and moves ahead, that will not dither or deny, but that really rises to the occasion and acts quickly. The second is we need to build the basic public health abilities that we've talked about to be able to prevent and quickly respond to. That's a platform. The third is focus on prevention – on good hygiene, on mosquito control. The fourth is to really understand communication. Social media, for example, is a double-edged sword. It spreads falsehoods and it also helps you understand how people are thinking about it. And number five is innovation. We need new vaccines, new diagnostics. We also need a even better early warning system. We've been able to reduce hurricane deaths 95 percent in the last 50 years with good early warnings. Number six is investments and our calculation is that if we put together the health systems part of it, the innovation part of it and the emergency response, that's about $1 per person per year, and finally everything that we've seen tells us that we will fall back into complacency unless we really have strong advocates and a mobilized and engaged citizenry in keeping the investments and the work happening between outbreaks.

CURWOOD: So, in your book, you raise a positive example of how in China they had trouble with SARS the first time around, but the second time around the outcome was much better. Tell me that story, please.

QUICK: So, just to put this in perspective, SARS, which appeared in China in 2003, was the first really new virus of pandemic potential in this century.

CURWOOD: And just for the record, in case people don't remember, SARS, of course, stands for Sudden Acute Respiratory Syndrome, if I recall correctly.

QUICK: Yes, indeed, and it can be rapidly fatal. So, it was totally unknown at the time that it hit. And there's this man who took it to Hong Kong on the ninth floor of the Metropole Hotel, and from there it spread to 27 different countries within a matter of weeks. WHO quickly reacted and those countries reacted. It was probably a plane ride away from getting into countries that didn't have the systems and we may still be living with this virus.

China in the first few months of it kept denying, and only when they were called to task by the WHO director general in public did they own up to it. This was a virus that had come from bats to a delicacy food called civets which is one common source of these epidemics, this so-called bush meat. So, China mobilized and really got vigorous in doing the inspections and setting up some rules and put in strict controls, and they have now dealt with outbreak after outbreak of influenza, dangerous influenza, in their poultry and all, by using the same control techniques and all that they developed with SARS.

CURWOOD: Dr. Quick, what's the single most important thing you want your readers to walk away with after reading your book or listening to our discussion?

QUICK: That the threat of major epidemics and pandemics is real. The scientific and public health community know what to do, but we're not moving fast enough with enough leadership and enough resources to protect us.

CURWOOD: Dr. Jonathan Quick, Harvard Medical School. Thank you so much for taking the time today.

QUICK: Thank you, Steve.

Links

TIME: “Our Complacency About the Flu is Killing Us” by Jonathan Quick

The Wall Street Journal: “An Action Plan for Averting the Next Flu Pandemic” by Jonathan Quick

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth