Turning up the Heat on Frigid Offices

Air Date: Week of August 26, 2016

Air-conditioning was invented in 1902 by Willis Carrier. By the 1950s, sales of window air-conditioners were booming, bringing affordable climate control to the home. (Photo: Jason Eppink, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

To combat summer’s hot and sultry weather, many US office buildings crank up the air-conditioning. But this sparks conflicts, as men feel comfortable but women shiver and don fleeces. Lou Blouin of the Allegheny Front reports on how these arctic offices became ubiquitous, and Jennifer Amann of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy tells host Steve Curwood how much could be saved if they turned the thermostat up a few degrees.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s an encore edition of Living on Earth, and I’m Steve Curwood. Well, the Northern hemisphere summer is winding down, and the days are growing shorter. But throughout these hot months, there’s been a continuing gender divide inside office buildings, with the dog days of summer demanding sweaters and scarves – at least for some folks.

MAN: "My little cubicle is just about right. I wear long pants -- they're wool -- and I have a long-sleeved shirt; I wear a bowtie every day."

SECOND MAN: "I personally feel fine with the air conditioning on, but I do notice that some people in the office get cold very easily. Uh, more women. Definitely more women."

WOMAN: "These offices are like sitting at the bottom of an ice cube tray: they're separated by walls but not all the way up. These are the ice cube trays in terms of how darn cold they are!"

SECOND WOMAN: "I keep a blanket at my desk for when I need it, or a shawl."

THIRD WOMAN: "It's cold. Very cold."

WESA reporter Margaret Krauss bundles up at the Community Broadcast Center in Pittsburgh, August 6, 2015. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

CURWOOD: That’s an unscientific sampling of opinion in Boston – but the same drama is playing out all over – including inside radio station WESA of Pittsburgh, as Lou Blouin of the Allegheny Front reports.

BLOUIN: Forget the tense staff meetings. Forget the latest workplace romance. By far the hottest drama in an office building in the summertime is the war over the thermostat.

PAGE-JACOBS: I wouldn’t call it a war. I would call it a dispute. And I think I would also call it an uneasy peace.

BLOUIN: That’s WESA afternoon host Larkin Page-Jacobs. And in our office here at the radio station, she's one half of an ongoing head-to-head over the temperature in the on-air studio.

PAGE-JACOBS: Josh comes in and turns it all the way to cold for his morning shift…

BLOUIN: She’s talking about Josh Raulerson, WESA’s Morning Edition host.

PAGE-JACOBS: But then when I come to do my shift, it is freezing. I didn’t really know how to address it. You know, sometimes I was a little vindictive, I would push it all the way to hot. And so when he would come in the morning, ou know, he’d feel like he was boiling.

RAULERSON: I’d get in here at 4 in the morning, and I come into that studio and it is stifling…

BLOUIN: That’s Josh Raulerson…

RAULERSON: So I always have to put the thermostat on full cold. And it became quickly apparent to us that we, like, couldn’t agree on where it should be set.

BLOUIN: And that, as you probably know if you work in an office, is not all that uncommon. There are even studies to back that up…

HEDGE: Well, if you look at studies of office workers, and the kinds of things that they complain about, thermal issues are number one.

WESA radio hosts Josh Raulerson and Larkin Page-Jacobs have an ongoing feud over the temperature in the on-air studio. She likes it warmer; he likes it cooler—which is not an uncommon disagreement among men and women in shared work spaces. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

BLOUIN: Cornell’s Alan Hedge has been studying this issue for more than 40 years. In fact, he published the first research on a topic that’s getting a lot of attention today: the differences in thermal comfort between men and women in the workplace.

HEDGE: And what that research showed, of course, was that women were experiencing more issues at the temperatures that were then being set in the environment, which are the temperatures that still tend to be used today.

BLOUIN: In fact, a study just published in the journal "Nature Climate Change" found that the standards of comfort that have endured since the Depression era are likely based on the metabolic rate of a 40-year-old, 155 pound man. And the problem with that, Hedge says, is that women, for a variety of biological and cultural reasons, tend to be colder than men in offices. But Hedge has also found evidence that the average office temp. of 70 degrees in the summer, isn’t really doing anybody much good when it comes to productivity. He says it’s always been assumed that if people are a little bit cool, they’ll do more work.

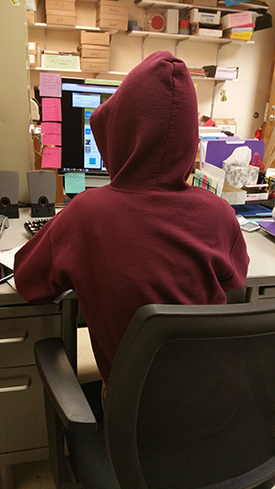

A hoodie is de rigeur in this woman’s office, despite the outdoor temperature of 85-degrees. (Photo: Naomi Arenberg)

HEDGE: In reality we find the opposite in office workplaces. We find that when people are in an environment that they find to be too cold, typically a temperature like 68 to 70, they do up to a third less work on their computers than if they’re in an environment that is more comfortable.

BLOUIN: That would be something around 76 degrees, which Hedge says, is the temperature where workers are the most productive. Which means, bottom line, we are over air-conditioning our workplaces in the U.S. In fact, geography plays a huge role in what your perception of comfort is. He’s found that people from tropical countries prefer the thermostat in the 80s. And in Japan, they’ve had success cranking the thermostat up to 82, while relaxing the clothing policy at work. Meanwhile, in the U.S. we continue to throw away a ton of money and energy by loading up on weapons to win our own office AC wars.

HEDGE: One of the ironies is that when you look at the sales of personal heaters, the peak months are July and August—which is crazy. It means the company is paying money to over-cool the air. And then you’ve people who are actually trying to warm the environment up.

BLOUIN: Where we’re heading Hedge says is into an era of more and more customization. Right now Cornell is helping to develop a technology that sort of does the inverse of what we do now. It would leave temperatures a little higher in the office overall, and then provide high-tech cooling at the desk-level for people who get too warm. He says it could be on the market by 2019. But we don't need to wait that long to turn up our thermostats, let people wear shorts to work, give workers desk fans, and in doing so, make everyone around the office a little bit more comfortable. I’m Lou Blouin.

A woman keeps a shawl along with a jacket at her desk, anticipating the effects of air-conditioning. (Photo: Naomi Arenberg)

CURWOOD: Lou Blouin reports for the Allegheny Front. Well, since these arctic offices seem so ubiquitous, and the complaints are such an old story, why is it still going on? That’s a question for Jennifer Amman, the Buildings Program Director for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. I asked her if this all isn’t kinda nuts.

AMANN: It is crazy, and I have heard it all before. This is a long-standing issue with many causes and in fact we suffer from it ourselves. Even at ACEEE, we have folks walking around in fleeces in mid-summer to stay warm in our office, and I know from our personal experience even in our own office space it can be a real issue for morale. It's very hard to keep employees happy when they're uncomfortable physically in their environment.

CURWOOD: So people are uncomfortable, unhappy, too cold, and it must cost a fortune to keep it too cold.

AMANN: That's right. Cooling is one of the largest energy users in commercial buildings, particularly offices, and so this is a real opportunity to change that, and I think we're seeing a number of changes in the types of technologies that are available, the increasing number of controls and sensors, new types of systems that are better able to operate at different loads, and even new systems that can allow users to have some input and even individual control over heating and cooling of their own spaces.

CURWOOD: Imagine that. Somebody sitting at a desk able to control the temperature where he or she is sitting? I mean, I don't think I have ever been in a large office where that's even possible.

For every degree the thermostat is increased during the summer, offices gain energy savings of two to three percent. This means that a difference of 72 to 77°F can save as much as 15%. (Photo: AJ Batac, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

AMANN: Right. Well, as buildings are increasingly retrofit and with new construction it becomes more possible to do these things but it might take awhile to get the technology changed out and get the new systems installed, but in the meantime there are lots of other things that can be done. Just installing more thermostats and working harder to make sure that the conditions throughout the space actually reflect the temperature settings on the thermostat, making sure sensors are in the right place, you know at the level where people are sitting. And then there are a number of interesting apps coming online that allow users and occupants within the space to record their comfort at various times of the day. There are activities that can be done to come in and more regularly check out the systems within buildings and now we're able to do that much more in an automated fashion. These things can all restore the system, find out where the deficiencies are, correct them without requiring an upgrade to the whole heating and cooling system.

CURWOOD: Jennifer, what are some of the behavioral changes that can help save energy in the summertime?

AMANN: So, one of the biggest changes would be to have everyone dress for the season, and that would allow building operators to set the temperature at a more appropriate level. Over time I think this has become more of an issue because a lot of the ideas about how cool it should be an office space came when the air-conditioning was new, you know it was very much a sign of prestige and luxury to have a cool space and you had men wearing suits all summer and you had even women wearing stockings and you know much more layers of insulation. But now we find folks are wearing much more casual clothing.

CURWOOD: The typical office today seems to be set for 70 degrees, maybe 72. What if we set it to 77 given the concerns we have about energy use in relationship to climate change and overall efficiency?

Jennifer Amann is the Buildings Program Director at ACEEE. (Photo: courtesy of ACEEE)

AMANN: The general rule of thumb is that you could save 2 to 3 percent for each degree that you raise the temperature. So going from 70 to 75, or 72 to 77, you would looking at 10 to 15 percent energy savings just from that one simple measure, and just because we have women complaining because they are freezing and men saying “I'm OK, I'm comfortable at the lower temperature”, doesn't mean that the men wouldn't also be more comfortable at a higher set point. So really being able to move forward to that type of an interior temperature could reduce environmental impact, cut energy bills substantially, and help us all be a little bit more comfortable and more productive and happier in our workspaces.

CURWOOD: Jennifer Amann is the Buildings Program Director for the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy in Washington. Thank you so much, Jennifer.

AMANN: Thanks, Steve. My pleasure.

Links

Allegheny Front’s “Why Frigid Offices are Bad for Everybody”

When it comes to studies of office complaints, thermal issues poll highest.

Differences in thermal office comfort exist between countries. Some can take the heat.

“Chilly at Work? Office Formula Was Devised for Men”

About retrocommissioning to improve energy efficiency

Temperature standards developed by ASHRAE

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth