Tips for Tackling Food Waste and Low-Waste Living

Published: May 20, 2020

Between food that goes to waste in distribution and in-home refrigerators, a third of all food produced is wasted. (Photo: Stephen Rees, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

(stream/download) as an MP3 file

Long before the COVID-19 disruptions forced dairy farmers to dump swimming pool quantities of milk into fields, a third of all food produced was going to waste. That waste has huge consequences for hunger and the climate, but it's also a major opportunity to reduce food waste, feed the hungry, save money and reduce carbon emissions.

Also, sustainable living can be as much about returning to old, thrifty traditions as it is about innovative technologies. How to make your own food scrap soup, orange peel cleaners and more.

And a team of paleontologists in New Zealand has discovered fossils of the largest known parrot to ever exist, estimated to be a whopping 3 feet tall and 14 pounds.

CURWOOD: Hi, I’m Steve Curwood and today on the Living on Earth Podcast we’ll take a look at food waste in the United States amid the coronavirus pandemic and we’ll have some simple tips to reduce our own household waste.

But first, your support helps make it possible to bring you this podcast, so please contribute what you can.

Five dollars or more makes a difference.

You can donate right now at LOE.org and thanks!

[THEME]

CURWOOD: Around the world more than a one-third of all food is wasted. In less affluent countries a lot of food becomes spoiled on the way to market, but in the US and other rich economies most food is thrown out at home because it’s rotted in the fridge or on the counter. And the numbers are huge. On a yearly basis food waste accounts for more than 3 gigatons of carbon dioxide, about a third of the human CO2 contribution to climate disruption. And with the closure of many restaurants and schools amid the pandemic, interruptions in food supply chains have led to even more food waste. John Mandyck is CEO of the Urban Green Council and co-author of the book Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger, and Climate Change. He joins me now. John Mandyck, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MANDYCK: Hey, Steve, it's great to be back on the program.

CURWOOD: Wonderful to have you. We're seeing reports that say gallons of milk are being dumped and fields and fields of vegetables are being plowed under. What's going on?

MANDYCK: You know, Steve, when I see farmers having to dump milk or plow under vegetables, I think about three big things. First thing I think about is that this shows the short term balance in our food supply. Disruption travels very fast. Think about the egg that was served in the restaurant. That egg got to that restaurant just one or two days ago. If the restaurant closes, the chicken doesn't know that. The eggs keep rolling. And so the farmer is left with a problem that he has to deal with. And so that's what we're seeing with the short term balance in our food supply. The second thing I think about is the lack of refrigerated storage for food banks. This has always been the case-- it's always been a problem. If food banks had proper refrigerated storage, all this milk that's being dumped under could have gone somewhere. And that's the plight that the farmer--has farmers say, I wish I had someplace I could deliver this milk. And the third thing this points out is that we're actually pointing the finger in the wrong place.

CURWOOD: Oh?

In the United States, most food waste happens right in our own refrigerators. (Photo: chinwei, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MANDYCK: You know, our food production and distribution in the United States is very well calibrated. Our problem is with consumers in the United States. The number one place we waste food in the United States is at the household level. We did that before the pandemic. We're doing that during the pandemic and we will do that after the pandemic. Food is the number one item in US landfills. That didn't come from the farmer --that came from our waste bins.

CURWOOD: One of the interesting aspects of the COVID crisis and the isolation associated with it is that I think more of us are cooking. To what extent do you think cooking at home will raise awareness for people about how much food has been historically wasted at home?

MANDYCK: I think it will. I mean that the closer we can become connected to our food, the better we'll understand it. You know, for a long time, we've thought that grocery stores were these magical places where, you know, we buy yogurt, we don't use it, we throw it away, we go back to the grocery store, and guess what the yogurt is back on the shelf like it magically appeared. And so we bought it again. You know, the pandemic is showing us with shortness of supply chains that well maybe grocery stores aren't the magic places that we thought they were because by the way, the yogurt wasn't there when you went back. And so hopefully it is bringing people closer to their food, starting to question, Well, why wasn't the yogurt there? Well, there's a long distribution chain to get the yogurt there. And so the closer we come to our food, I think the more respect we'll have for where it came from, how it got to our table and how we actually should cherish it more.

Food banks have limited refrigerator space, so excess milk, eggs or other highly perishable foods must often be disposed of rather than distributed to hungry families. (Photo: Staffs Live, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what about the whole notion put by more people, I don't know how many more, are gardening out there? And it's harder to throw away that lettuce that you've grown with weeding all the stuff you have to do, as opposed to just simply having picked it up at the store. To what extent do you think that making food closer to home might help with this food waste problem?

MANDYCK: I think it does. If you invest the time to grow your own food in the backyard, you literally have sweat and tears invested in your food supply. So I think that helps, but it points out another issue. I don't know if you've ever tried to grow zucchini in your backyard. The zucchini comes in and on and off switch. And so you wait all season and then you get two bushels of them.

CURWOOD: Yeah, some of them are the size of baseball bats as well if you're not careful.

John Mandyck is the CEO of the Urban Green Council and author of Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change. (Photo: courtesy of John Mandyck)

MANDYCK: That's right. And so I know in my house, we can't eat all of those. So it really underscores the issue in our food system, is that there's literally a bounty of riches when the harvest comes and so you have to find a way to get rid of that zucchini. Otherwise you're gonna throw it away, too, right? So you're making zucchini cakes, you're shredding it, you're freezing it. There's only so much that you can do and then you start your own food distribution system by giving it to your sister, your mother, your neighbor. But that too helps underscore the bigger picture that we have with our global food supply.

CURWOOD: So what do you recommend that we do as a nation and as individuals to reduce food waste then?

MANDYCK: Well, you know, as a nation, our number one issue is at the consumer level. That's where we're throwing away most food. It's the same in Europe, it's the same United States, it's really a rich country dilemma because we can afford to do it. Food is relatively inexpensive in the United States. And if we throw away the 99 cent yogurt because we were confused about the date label, we simply go back and get another 99 cent yogurt. So we have to have consumer education and awareness to understand the scale and consequences of what happens when we throw away that food. We have to have public policies that encourage us not to do that. And that means encouraging date labels that are rational and makes sense. This has happened in Europe. There's been strong campaigns over the last decade to encourage consumers to waste less food. And we've seen that those have worked. We need those campaigns in the United States. If you look globally, though, two thirds of all the global food supply is lost at that production and distribution level. This is an emerging economy problem where food rots in poor transportation networks, it rots in open air markets, it rots in wet markets in China, which is relevant to the pandemic that we're having today. And so we have to find ways to modernize that production and distribution system in emerging economies if we really want to tackle the issue on a global level.

Self-isolation has many of us growing vegetables, cooking more and getting a little more in touch with our food. (Photo: normanack, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what can we learn from other countries that have tried to tackle food waste?

MANDYCK: I'll point to two. In the United Kingdom, they started a consumer campaign called Love Food Hate Waste, where environmental organizations and hunger organizations partnered with the grocery stores, and the campaign has gone well. Over the last decade, they tell us that they've reduced household waste by 20%, which is a huge improvement. So that works well. France is a good case study in a different direction. A few years ago, France passed a law that bans supermarkets from throwing away food that is otherwise good to eat. Now, that sounds like a great policy that that sounds like it makes a lot of sense. But we can actually learn a lot from the French law. What happened is the supermarket said, okay, we can't throw away the food, we'll deliver him to the food banks. So if you run a small food bank in a small French village, one morning, you come to work and you could have three boxes of apples. That's great. You're going to distribute three boxes of apples to those in your village that you know they need them. The next morning, you come to work you find you have a truckload of eggs. What are you going to do with a truckload of eggs? You don't have the refrigerated capacity that we talked about. You don't have the distribution system, you can't get them out fast enough. So what happened in a inverse way is that food banks were starting to throw away the food. And, you know, kind of standing up and saying what just happened here? And so it's really questioned the role of policy policies needed. But we have to understand the unintended consequences of those policies. And the French law was, as has been a great lesson to the world.

The strawberry that molds in your fridge carries an additional carbon load from all the transport, refrigeration, and packaging it took to get from the field to your home. (Photo: Kevin Payravi, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: What's the impact of all this food waste on our climate do you think?

MANDYCK: Well food waste is, to me one of the sleeping giants of climate change. If you measure the carbon footprint of all the food that we lose or throw away each year, and we measure it as a country, it would be the world's third largest emitter of greenhouse gases. And so we need consumers to understand that particularly in the United States to help change consumer behavior that when we throw an item in the landfill, we just threw a ton of carbon in the landfill. An example is a strawberry. Steve, you and I are on the East Coast right now. If we eat a strawberry today, it came to us from California. It took a lot of carbon to prepare to grow that strawberry. The farmer had to go out in the field with a tractor. He had to plow the field under, he had to plant the strawberry, he had to water the strawberry, use a lot of water. Then he had to harvest a strawberry. Using carbon he had to bring the strawberry from the field into a packaging place which burned electricity. We took plastic which is carbon based and wrapped it in plastic then we put it on a truck and we brought it across the United States burning carbon. It got to the your grocery store, it sat on the shelf, the store is burning carbon waiting for you to come. Maybe you got in your car and burn carbon to go get the strawberry, brought it back you put it in your refrigerator which is plugged in burning carbon and then you forgot to eat it and it went bad and it got moldy and you threw it away. It would have been better to throw the strawberry away in the field from the carbon standpoint because it was fully carbon loaded when it got to you the consumer. And so we need to understand that it's not just throwing away the strawberry. It's throwing away all the carbon that went into getting the strawberry to you and to me.

CURWOOD: John Mandyck is CEO of the Urban Green Council. He's also co author of the book Food Foolish: The Hidden Connection Between Food Waste, Hunger and Climate Change. Thanks so much, John, for taking the time with us today.

MANDYCK: Steve, it's been great to be on the show.

[MUSIC]

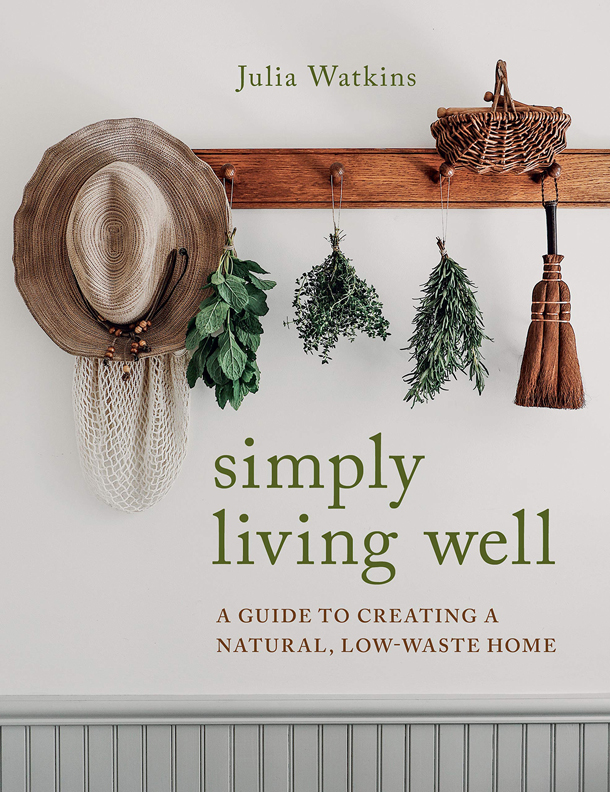

In Simply Living Well, Julia shares waste-reducing recipes, as well as instructions on how to make your own natural cleaning supplies and wellness products. (Photo: Courtesy of Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: When Julia Watkins started thinking about food waste in her own home she took action to reduce her household waste and live more simply. She shares pictures of her low waste journey on Instagram and has amassed nearly a quarter of a million followers. And as a social media influencer she is now sharing some of her strategies and recipes in a new book, Simply Living Well: A Guide to Creating a Natural Low Waste Home. She joins us now from near Chicago. Julia Watkins, welcome to Living on Earth.

WATKINS: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: A lot of people I imagine are starting out are looking again at the simplicity side of having really low waste, because we can't go anywhere. So in this moment, what are a couple of things that you would point out to people who really maybe haven't thought about trying to live the low waste or zero waste level--things that they could simply do right now in their homes in apartments, given the challenges that we have?

WATKINS: So my book was actually inspired by my great grandparents' generation. A lot of my style of low waste or zero waste is very old fashion. And, you know, they all survived the Great Depression by virtue of being resource conscious. So the recipes in my book are very, they're very within anyone's reach. For example, to make a veggie stock, you use scraps from the vegetables you've used for cooking throughout the week, so you don't have to go out and buy a carton of veggie stock, and you also don't have to buy new vegetables for it. When you make nut milk, you can use any kind of nut you have. You don't throw the pulp away at the end-- you use it to make crackers, you use it to make truffles. When you eat an orange don't throw the peel away--you can put it in a jar of vinegar and let it infuse for a couple of weeks and then turn it into an all-purpose cleaner.

One of Julia’s favorite recipes is the vegetable stock she makes out of her kitchen scraps. (Photo: Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: Or you could do what my grandmother did--make candy out of this stuff.

WATKINS: Really?

CURWOOD: Yeah, those orange rinds, those grapefruit rinds, they would candy them at the holidays.

WATKINS: I haven't try that yet, but I've wanted to. Yeah, you can use orange peels for all kinds of things.

CURWOOD: So you're really big on vegetable scraps. And in fact, you have a recipe for a soup made from vegetable scraps. So talk to me about that.

WATKINS: Yeah, when I first started going zero waste, I noticed a lot of people making this veggie scrap stock. So I tried to figure out a way to make it really delicious. And basically what I do is save veggie scraps and past-peak produce, I prepare veggies throughout the week, I wash and save stalks and peels and leaves, and then I store them in a paper bag or a mason jar in the refrigerator. And when I have about four cups worth, I make the stock. So it's not as easy as just throwing the stock in a pot with some water. You want to give it a really strong flavorful base. So just chop up a couple of onions, couple of carrots, some celery and some garlic and put a little oil in the bottom of your pot and saute them until they're tender. And then just all you have to do is add your four cups of scraps, eight cups of water, let it boil, then simmer for an hour. And that's it. That's your veggie scrap stock. You can let it cool and bottle it up in mason jars and put it in the fridge if you're going to use it that week or you can freeze it, too. It freezes for up to six months to a year.

Julia grows many of her own vegetables in a garden outside her house. (Photo: Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: Then take me to the next step. So what do you get to use this for?

WATKINS: I use it in a lot of the recipes in the book. A lot of the recipes come from harvesting vegetables from my garden. So I use it for a carrot tomato soup. And I use it for an onion garlic soup that uses 40 cloves of garlic

CURWOOD: 40 cloves of garlic.

WATKINS: Yeah

CURWOOD: A little hot for the mouth, don't you think? No?

WATKINS: Well, you roast it and it takes a lot of the sting out. It's delicious. So I use it for that and we stir fry a lot at our house. So I'll use it for stir fries. I go through the stock pretty quickly. I usually make this every Sunday as part of my weekly rhythm.

Julia considers traditional, old-fashioned cleaning supplies to be more beautiful than the more modern plastic ones. (Photo: Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: Julie, in your new opinion, why should we be doing this? Why should we be trying to minimize the waste that we create on the planet?

WATKINS: Well, I think there's different ways to look at it. There's sort of the environmental reason. We know that we're extracting resources faster than is sustainable. We know that populations are growing and that eventually, things could get really difficult for people. For me. I know that I care about the natural world. I've had these wonderful experiences. For me, it doesn't come so much from my head. It's not so intellectual. It's a little more from like my heart, I guess, as cheesy as that sounds, but I've had these experiences. I do think I have a connection to the natural world. And it makes me feel good to be authentic to be who I say I am. And I think I've always said I would do this, even if we weren't in the midst of a climate crisis or a coronavirus. But it really, we have all the reason to do it if it's coming from an intellectual place.

CURWOOD: How do you reach people who are so driven by the brand, the label, the chicness, the being able to, what, we're moving ahead, aren't we? We must do something that's new and modern. How do you address those folks when they can look and see that so many of the things we recommend, come from, well, a century ago?

Home Grown Herbs (Photo: Julia Watkins)

WATKINS: I think you have to make it beautiful for those people. And it is beautiful. If you look at old fashioned cleaning tools, they're not made out of bright pink plastic poles or handles, right? They're made out of beautiful wood. And the bristles are made out of horsehair and real natural fibers. They're beautifully, they're aesthetically pleasing. I think a lot of people get into zero waste and natural living because of the aesthetics. And I think that's fine. Once they're there. Just try to keep them there. You know? But I think sustainability has grown because it is beautiful. And it does appeal to people's sense of style and personal aesthetic.

CURWOOD: And what would you say to folks who are now stepping into a very difficult time economically? How does your approach to natural low waste save money?

WATKINS: Well, a lot of the the recipes use what you already have. They use things that your grandmother used to when she was strapped for cash, too. They're inspired by the idea that you can grow herbs, you can dry them, you can preserve them, and then you can use them for every area of your home.

Julia Watkins lives near Chicago. (Photo: Courtesy of Julia Watkins)

CURWOOD: What inspired you to get involved in all of this?

WATKINS: I think mine happened in a lot of different stages. So my professional background is all in environmental work. I was a Peace Corps volunteer in a tiny little village in Guinea. And I saw people literally living in direct connection with the environment. And I saw them living simply and slowly. And I was so inspired by people just making do with what they had. So I think once my first child was born, and I was home for a while, I wanted to integrate everything I've learned through my education and my experiences with my actual life. That's when I started cooking with real ingredients and real food and one thing led to another. It was like a rabbit hole and then I was making my own cleaning supplies. And then I was growing a garden and learning how to sew and learning how to knit. And for me it was very empowering. I think sometimes people think of the 1950s when they think of some of these skills, but when it's a choice, when you want to learn them, it's extremely empowering. And then a time like this, I feel resourceful. I don't feel worried about things not being on the shelves at the grocery store, because I can probably make it or get by with what I have.

CURWOOD: Julie Watkins' book is called Simply Living Well: A Guide to Creating a Natural Low Waste Home. Julia, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

WATKINS: Thank you for having me. Thanks so much.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: To get the stories behind the stories on Living on Earth as well as special updates, please sign up for the Living on Earth newsletter. Every week you'll find out about upcoming events and get a look at show highlights and exclusive content. Just navigate to the Living on Earth website, that's loe.org, and click on the newsletter link at the top of the page. That's LOE dot ORG.

[MUSIC]

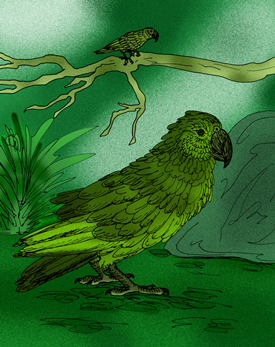

An artist’s reconstruction of Heracles inexpectatus by Dr. Brian Choo from Flinders University. (Photo: Brian Choo)

CURWOOD: Paleontologists recently unearthed a surprising find in New Zealand. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman explains in this week’s note on emerging science.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: Paleontologists in New Zealand have found fossils of the largest known parrot to ever exist. Researchers say the newly described species of extinct parrot, Heracles inexpectatus, would have been about 3 feet tall and 15 pounds. Scientists suspect the extinct bird probably had a massive beak that it may have used to rip open anything it liked, including other parrots. The fossilized leg bones of the giant parrot were unearthed at St. Bathans, New Zealand in 2008. Researchers thought the bones were from an extinct species of eagle. In fact, the bones sat with a collection of eagle bones for about 10 years until a graduate student realized that the fossil drumsticks were actually from a species of parrot that lived around 19 million years ago. Prior to this discovery the largest known parrot in the world was about two feet tall and around 9 pounds.

This artist’s rendering compares the giant parrot, Heracles inexpectatus (below), to a similarly-extinct parrot, Nelepsittacus donmertoni (above). (Photo: Apokryltaros, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

That’s the kakapo, a flightless, critically endangered parrot in New Zealand. In fact, New Zealand is a hotspot for giant birds. The island’s now extinct Moa were up to 12 feet tall and more than 500 pounds. Moas resembled their Australian cousins, emus. But until now no one had ever found an extinct giant parrot. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show.

Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I'm Steve Curwood.

Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green, and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Links

NYTimes | “Dumped Milk, Smashed Eggs, Plowed Vegetables: Food Waste of the Pandemic”

Julia Watkins’ Instagram Account, Simply Living Well

Purchase Simply Living Well: A Guide to Creating a Natural Low Waste Home

National Geographic | “This Toddler-Size Parrot Was A Prehistoric Oddity”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth