May 5, 2017

Air Date: May 5, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Breaking the Barriers to Offshore Oil

View the page for this story

Keen to roll back regulation, the Trump administration wants to overturn the Obama-era ban of offshore drilling in the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, so the President has issued an executive order to return these sites to the market. Founding Director of the Center for Global Energy Policy, Jason Bordoff, joins Helen Palmer to discuss whether the low price of oil makes this drilling uneconomic and the legislative battle about to boil under the sea. (07:05)

Follow the Oil Spill Data

/ David LevinView the page for this story

To grasp the long-term effects of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil blowout, a team of U.S. and Mexican researchers is examining the Ixtoc oil spill off the Mexican coastline in 1979. David Levin reports on how researchers turned satellite data from the 70s into a map of exactly where all of that oil traveled. (06:55)

Marching for the Climate, Before and In Trump’s Era

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Hundreds of thousands worldwide rallied for the People’s Climate March on April 29th, but the mood was bleaker than the First People’s Climate March in New York City in 2014, when citizens demanded nations craft an international climate treaty. Now, a year after some 200 countries signed the landmark Paris Climate Agreement, marchers worry that the Trump Administration might pull the U.S. out of the accord. Host Helen Palmer reports on the Boston march and the changing landscape for climate action. (07:30)

Novel Man-Made Minerals

View the page for this story

Despite their rigid molecular composition, minerals are sensitive to humanity’s impact on the planet. Now scientists have discovered about two hundred new compounds, created accidentally as a result of human activity in such places as mines or under the sea. Robert Hazen, a research scientist at the Carnegie Institution of Science, describes the discoveries to host Helen Palmer. (06:40)

Birdnote: Motherly Instincts

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

No two species of bird approach parenthood in quite the same way. As Mary McCann explains, the division of responsibilities between mother and father is often unequal. (02:00)

Unraveling the Myths and Mysteries of the Tides

View the page for this story

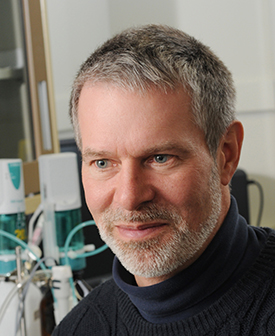

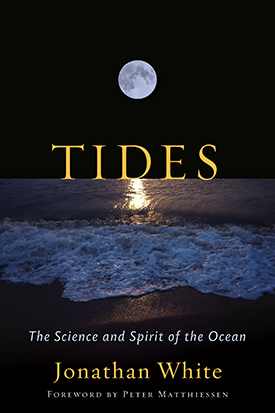

Tide tables report to the tenth of a foot the fluctuations of sea level as the ocean ebbs and flows. And though the moon has the greatest influence on tides, there’s much more at play. Now a new book, Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean, illuminates how they work. Mariner and author Jonathan White regales host Helen Palmer with the tale of a boating mishap that provided inspiration for the book, and the myths and history that roll in and out with the restless seas. (16:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Helen Palmer

GUESTS: Jason Bordoff, Robert Hazen, Jonathan White

REPORTERS: David Levin, Mary McCann

[THEME]

PALMER: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

PALMER: I'm Helen Palmer in for Steve Curwood. A new Executive Order would roll back President Obama’s moratorium on drilling in Arctic waters and off the Atlantic coast.

BORDOFF: I think the one way to read the Executive Order that President Trump signed is in many ways almost like a laundry list of everything you could possibly imagine doing that would be supportive of offshore oil and gas production. It does not mean in the end that all of those things will happen, and it would not be easy to do all of these things.

PALMER: Legal challenges are certain and delays inevitable. Also, what’s bringing thousands of people onto the streets to protest.

MILLER: When you listen to the news from Washington, there’s such a sense of powerlessness. Every day, you can’t believe, there’s yet another assault. Maybe alone, I don’t have any power but when I gather with my people, then I have some power.

PALMER: We’ll have that and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Breaking the Barriers to Offshore Oil

The Maersk Developer drills an exploratory well in the Gulf of Mexico in 2014. (Photo: JournoJen, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PALMER: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Helen Palmer in for Steve Curwood. The Trump administration wants to tap potential oil and gas reserves in the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, so on April 28, the President signed a new Executive Order titled “America-First Offshore Energy Policy”. The order would reverse federal protections President Obama signed for parts of Alaska’s Chukchi and Beaufort Seas and in the Atlantic. He used the 1953 Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, intended to place them permanently off-limits for drilling, and environmental activists argue these protections can’t be reversed.

Jason Bordoff is the Founding Director of the Center on Global Energy Policy, and he says it’s no surprise a new administration would want to rethink previous energy plans.

BORDOFF: It's not uncommon for new administrations to try to redo the offshore leasing program, and so, under President Obama, he had left office, putting in place a leasing program for 2017 to 2000-2022. You do these by statute, and President Obama has put several areas off-limits to drilling, perhaps most notably offshore Alaska. President Trump has come in and ordered his Department of the Interior to now redo the five-year leasing program and explicitly instructed them to include those areas in it. The one wrinkle this time is that President Obama -- beyond the five-year leasing program -- President Obama additionally used a seldom-used authority to remove large areas of Alaska and the offshore Atlantic from consideration for future leasing permanently, and that was something that hadn't really been done before. So, President Trump has ordered that that be rescinded. That will be litigated in courts by environmental groups, and we'll have to see what the courts say about putting areas off limits permanently, is that something a future administration can reverse.

PALMER: What was the reason that President Obama decided that he would want to take these areas out of possibility for leasing in the first place?

BORDOFF: They talked about the critical importance of these areas to marine wildlife, the corals there, the wildlife habitat, the sort of unique sensitive nature of the Arctic from a tourism standpoint, from a commercial and recreational fishing standpoint, from the shipping and transportation standpoint, and the potential that any sort of risk of oil and gas activity going wrong could jeopardize all of those things.

A polar bear sits atop sea ice floating in the Beaufort Sea off of Alaska. In 2016, President Obama used a little-known authority under the 1953 Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act to ban offshore drilling in Alaskan waters indefinitely. (Photo: NOAA National Ice Center, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0)

PALMER: So, the next step after the Executive Order was that Secretary of Interior Zinke had to produce a new five-year plan, and I gather he's done that?

BORDOFF: Well, he's just taken first step to direct a bureau within the Department of Interior to begin the process of redoing the five-year leasing program. So, this will take about two years for the administration to redo the five-year leasing program and try to open some of those areas like the Alaska and the Arctic. And then the question, of course, is once the lease sales are held, does anyone in the industry show up? And given how low the oil prices, is there any interest in going into these high-cost, complex areas like the Arctic?

PALMER: Well, that's obviously the question, particularly in the Artic we've seen that Shell Oil tried to drill a few years ago, and in fact gave up the effort after having running into several snags. How likely do you think it is that anybody will be interested in the Arctic, given, as you say, this low price of oil?

BORDOFF: I think it depends entirely on what the oil market looks like at the time. I think if tomorrow a lease sale were offered for sale in the Alaskan Arctic, it would, I think it's fair to say, it would generate relatively little interest. I don't think companies like Shell a lot of desire in this current oil market environment to quickly go back into these high-cost complicated areas, particularly given how promising on-shore U.S. oil development looks with the revolutions we've seen in shale, and how quickly those costs have come down. But I think the biggest impact on US oil production of redoing the five- year leasing program is creating the option, creating the potential for industry to go in and begin to develop these areas, if and when the market makes that a desirable thing to do, but that is not what the oil market looks like today.

PALMER: So, how about the potential leases off the Atlantic coast? Several of the governors there and several of the Congress people there are fairly strongly opposed to any thought of drilling off their coasts.

Oil seeps out of shale rock in Los Osos, California. New technologies for extracting oil from shale have dramatically transformed the oil market and kept the price-per-barrel unexpectedly low. (Photo: Rob Bulmahn, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BORDOFF: They are, and I think there will be a lot of opposition from many states along the eastern seaboard, and this is not necessarily a partisan issue. You see even Republican governors and states like South Carolina that have expressed opposition to opening areas of the Atlantic to drilling. So, I think that’ll be quite a contentious thing.

I mean, I think the one way to read the Executive Order that President Trump signed is many ways almost like a laundry list of everything you could possibly imagine doing that would be supportive of offshore oil and gas production. It does not mean in the end that all those things will necessarily end up happening and that, even if you did all those things, some may have more impact than others.

PALMER: So, these are kind of maximalist plans, as it were?

BORDOFF: I think it's fair to read the Executive Order as over-inclusive for the kinds of things one might do, and it's unclear in the end whether all these things will happen. And it would not be easy to do all these things. I mean, he has some things in this Executive Order like directing the Department of Interior to evaluate whether to reconsider rules that regulate how offshore drilling is done, the well control rule that was put in place after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Then, I think there are some things industry would support, but there are some that, you know, industry has geared up to operate in a certain way. It's not necessarily the case that they would want to see all these rules rolled back either.

Jason Bordoff is a professor of Professional Practice in International and Public Affairs at Columbia University and the Founding Director of the Center on Global Energy Policy. (Photo: Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs)

PALMER: Now, tell me about the fact that this Executive Order includes a review of whether Marine National Monuments, made or expanded in the last 10 years, have an impact on energy development.

BORDOFF: I think the provisions of the Executive Order on National Marine Sanctuaries is again, in part, an effort to be over-inclusive and sort of say, before we put areas off-limits to development its important… this administration wants you to really study what impact that would have on energy development. I am not aware of lots of resource rich areas and lots of interest from the industry and going into areas that were protected by the Obama administration as National Marine Sanctuaries.

PALMER: So, basically there are plenty of places where they could drill without going into marine monuments that might upset people even more.

BORDOFF: Yeah, there's enormous offshore resource potential especially in the Gulf of Mexico and the more controversial areas were especially offshore Alaska, but there are some who think that the oil price could spike again in a couple of years, if global oil demand remains strong, and for all the talk of peak oil demand and electric vehicles, we've seen projections of oil demand actually fall short each of the last two years. Oil demand’s been higher than we thought it would be, and we still see that today, and in that world we could see a lot more interest in leases in offshore Alaska.

PALMER: Jason teaches at Columbia University and is the Founding Director on the Center on Global Energy Policy. Thank you very much for spending the time with us.

BORDOFF: Thank you for having me. I appreciate it.

Related links:

- The existing 2017-2022 Outer Continental Shelf Oil and Gas Leasing Program

- The Hill: “Trump signs order to rollback Obama’s offshore drilling limits”

- The Washington Post: “Environmental groups sue Trump administration over offshore drilling”

- Reuters: “Obama bans new oil, gas drilling off Alaska, part of Atlantic coast”

- About Jason Bordoff

Follow the Oil Spill Data

The Ixtoc oil well blowout from a helicopter platform in the Bay of Campeche, Mexico. (Photo: NOAA)

PALMER: The destruction an oil spill in the Arctic could create was given sharp focus by the 2010 Deepwater Horizon well blowout in the Gulf of Mexico. It gushed nearly five million barrels of oil and broke all records, including one set by a 1979 spill off Mexico at the Ixtoc well that lasted nine months. Now a team of U.S. and Mexican researchers is revisiting Ixtoc to find out how the environment nearby has recovered, and learn how the area near Deepwater Horizon might look in the future. Their first step: some digital archaeology, dusting off satellite data from the late 1970s. David Levin has this report.

LEVIN: Studying an oil spill that happened nearly 40 years ago isn’t so easy, even one the size of the Ixtoc disaster. And that’s mainly because nobody’s really sure where all that oil went. In 1979, there was no way to map the spill, so millions of barrels went unaccounted for.

MURAWSKI: I haven’t seen any comprehensive maps that were drawn in the day.

LEVIN: That’s Steve Murawski, Professor at the University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science. He helps lead a group of scientists in the US and Mexico that are looking back at Ixtoc today. There’s really not much information on Ixtoc. By contrast, Deepwater Horizon was measured by multiple satellites, dozens of ships, and aircraft,

MURAWSKI: Deepwater Horizon was absolutely a unique event in terms of the amount and diversity of resources that were available to actually do this tracking. Y’know, people wanted not only to see the imagery at the wellhead, but they also wanted to know where it was, so that people could make up their own minds about the risk of oil coming ashore in different places.

LEVIN: In the 70s, though, that level of detail wasn’t even a possibility.

HU: [LAUGHING] No, no way.

LEVIN: Chuanmin Hu is an optical oceanographer at USF. He uses satellites to study modern oil spills. He says, the advantage is that a single satellite image lets him survey the entire Gulf of Mexico in one shot.

HU: Think about, if you want to do that with aircraft, it would take days or even months to have one complete view of the gulf, not to mention a boat. It takes years for a boat.

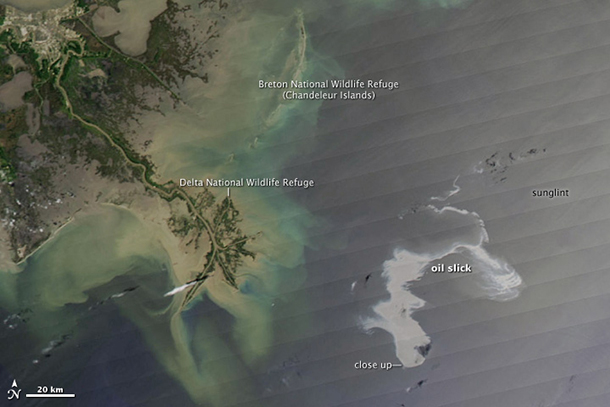

The Deepwater Horizon Spill in 2010 was extensively captured by modern satellite imagery. This image was taken by a Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

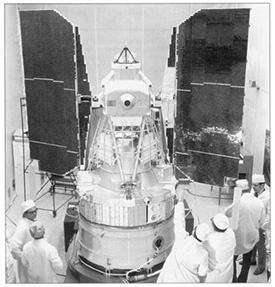

LEVIN: Back in 1979, though, a handful of planes and boats were pretty much all first responders had to work with. But what cleanup crews didn’t know was that a few hundred miles overhead two early satellite instruments were busy clicking away.

The first was the Landsat Multispectral Scanner, basically a sort of digital camera in orbit. The second was the Coastal Marine Color Scanner, or CZCS.

HU: At that time, satellites were just launched. You know, very few people knew how to use them.

LEVIN: And because of their orbits, they didn’t fly over the Gulf of Mexico that often. CZCS took measurements of the Gulf just once every four days.

HU: For the other sensor, every 16 days you have a measurement.

LEVIN: And that didn’t mean the measurements were even usable.

HU: Exactly. There’s no guarantee you have cloud-free data. On average in the Gulf of Mexico, the odds of having cloud-free measurement is one over three. So basically if you have three images a day, then you may have a cloud-free measurement.

LEVIN: But even with these limitations, Hu thought the old data might still come in handy. If he and his team could use it to piece together images of the Gulf from 40 years ago, they might be able to make a basic map of where oil traveled during Ixtoc, one that could help Steve Murawski’s team figure out which areas to to study first.

So Hu and his students revisited the old satellite files. They’re actually not that hard to get, just visit the NASA website.

HU: So everybody, not just from this country, but around the world, has access to that data. So that’s public domain. How you process the data, that’s the challenging part.

LEVIN: It means turning raw data from the satellites into an image, then figuring out which region of the Gulf it’s actually showing. And then, you’ve got to figure out if there’s any oil in the water, which isn’t always obvious.

HU: So the first thing is to look at contrast on the ocean surface. So any outstanding features, that’s a suspicious feature.

LEVIN: Hu says you can tell at a glance if the image just shows clouds, or stuff floating on the surface. But you can’t easily tell if the material on the water is algae, oil, or something else. To do that, you have to analyze the subtle colors of light being reflected and absorbed.

ERTS-1 -- The first Landsat satellite. (Photo: NASA)

HU: These well-designed sensors measure the different colors reflected from oil, from non-oil, and from other things in the ocean. And they each have different color shade measured by the sensor. So oil has a different shade than others, although your eyes can barely tell the difference.

LEVIN: So Hu’s grad student, Shaojie Sun started poring over all the data. He figured out — slowly — which measurements showed oil instead of clean seawater, and over the course of a few months, he squeezed out enough information to make this. A map.

SHAOJIE SUN: So I have a map of the Gulf of Mexico. In the lower left, the brownish color maps the Ixtoc oil spill.

LEVIN: On his computer screen, Sun points to a swirling brown streak near the Mexican coastline. It represents where oil traveled over nine months in 1979. In other words, it’s the first map ever to be made of the Ixtoc spill, nearly four decades after the well was plugged.

SHAOJIE SUN: It’s really exciting to map out a 40 years old oil spill, but other scientists can use my map and my work to do their own science.

LEVIN: Scientists like Steve Murwawski. He sees the work as a goldmine.

MURAWSKI: We looked at the map that we got from the satellite imagery as a treasure map. It’s incredibly valuable from a scientific point of view. And that treasure map has basically told us where to look for concentrations of oil, both on the bottom and also ashore in the shoreward areas.

LEVIN: Murwaski says that by dusting off old data, Shaojie Sun and Chuanmin Hu have created something entirely new, a tool that lets scientists revisit the past. It’s made possible the work that Murawksi and his team are doing on Ixtoc.

MURAWSKI: Mmm hmm, yeah. The new map that we have gives us not only a mosaic of what happened over nine months, so we can see the full footprint, but it also gives us some time slices of how that oil spill evolved over time.

LEVIN: The joint US-Mexican team is using Sun and Hu’s map to plan out where to take samples along the Mexican coast. They’re pulling bits of mud from the seafloor, collecting worms and other creatures living there, and they’re analyzing the water surrounding them, all based on the guidance they’re getting from 40 year old satellites. What they find now will help them understand the impact of Deepwater Horizon four decades in the future and tell whether the next generation of Gulf residents will still be feeling its effects.

For Living on Earth, I’m David Levin.

Related links:

- This piece is part of the PRX series The Loop

- About David Levin

- A previous Ixtoc story from Levin

- NASA Oil Spill Photo Gallery

[MUSIC: Dr. Michael White, “Give It Up – Gypsy Second Line” on Dancing In the Sky, Basin Street Records]

PALMER: Coming up...hundreds of thousands take to the streets to push for climate action. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dr. Michael White, “Give It Up – Gypsy Second Line” on Dancing In the Sky, Basin Street Records]

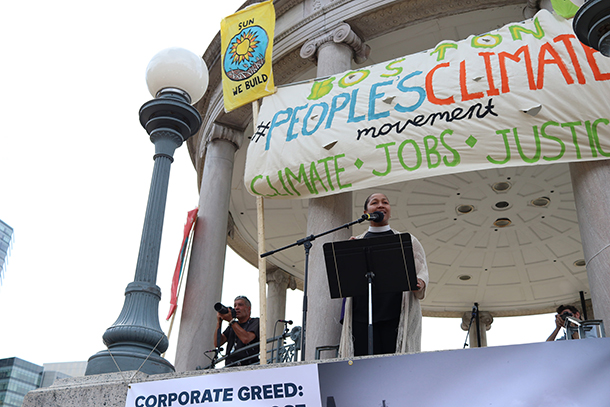

Marching for the Climate, Before and In Trump’s Era

Thousands rallied on Boston Common as temperatures climbed into the low 80s (Fahrenheit). (Photo: 350 Massachusetts)

PALMER: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Helen Palmer.

[MUSIC: “This is what Democracy looks like..." recorded live at the People’s Climate March in Boston]

PALMER: The message was clear at the People’s Climate March in Boston.

[MUSIC: “We are the leaders we’ve been waiting for”…]

Thousands rallied on Boston Common on April 29th, but in September 2014 nearly half a million people crammed the avenues of New York for the First People’s Climate March, to urge the nations to take bold action on global warming. It was the eve of the UN Climate Summit and the Living on Earth team was there. I was hanging out at 46th St and 6th Ave, and the atmosphere was joyful, almost like a carnival parade.

[MUSIC - BALKAN JAZZ BAND]

PALMER: There was a Balkan jazz band. There were singers and many familiar chants repurposed.

[PEOPLE CHANTING: “HEY-HEY, HO-HO, FOSSIL FUELS HAVE GOT TO GO!”]

PALMER: The organizers wanted a “big tent” because what’s happening to the climate affects everybody. More than 50,000 students marched. Over 1,500 different organizations were there - a strong labor contingent, including many from the Domestic Workers Alliance, brandishing brooms and mops. There were anti-nuclear campaigners, Veterans for Peace, many different faith groups, and Native Americans.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond is a Minister for Ecological Justice at Bethel A.M.E. Church in Boston and a leader with the Massachusetts Interfaith Coalition for Climate Action. (Photo: Nathan Bishop)

[NATIVE AMERICAN CHANTING WITH DRUMS]

ANSTER: My name is Britney Anster. I represent the Haliwa-Saponi nation of Hollister North Carolina. It’s important because we are nature. We are the air, the Earth, not just indigenous people, but all people. We share this communal Earth and we’re here fighting for climate justice, not just for us, but for all people, especially our future generations.

PALMER: Native Americans and Canadian First Nations were leading the march along with some of the other communities most affected by global warming, island nations and people on the frontlines who’ve already experienced weather extremes, people like Kathy Sykes from Jackson, Mississippi.

SYKES: I’m here because we as a people have to come together to do something about climate change. Mississippi has seen the brunt of it with Hurricane Katrina. We still have not recovered. We’ve had a big oil spill in the Gulf Coast. It is terrible. So we’re here fighting, trying to do whatever we can to draw attention to the need to stop climate change and save our world.

Climate activism is a family affair for the McDonalds. From left: 12-year-old Campbell; Dad Rick; in stroller, Charlie; Mom Kathy; 8-year-old Skyler, and 9-year-old Parker. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

[DRUMS AND CHANTING]

PALMER: And it seemed the nations were listening. The size and determination of the People’s March helped spur the momentum towards the crucial UN Climate Conference of Parties, COP 21 in Paris in December 2015. Urgency, diplomacy, and arm-twisting all helped persuade nearly 200 countries to sign onto the final Paris Agreement.

KERRY: This is a tremendous victory for all of our citizens, not for any one country or any one bloc, but for everybody here who has worked so hard to bring us across the finish line. It's a victory for all of the planet and for future generations.

PALMER: John Kerry, then Secretary of State, had put US credibility on the line to make this deal happen, and his rosy optimism was shared by the Climate Change Commissioner for the European Union, Miguel Arias Cañete.

“Yo People, stop with the CARBON!”, a dog’s sign read (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CANETE: With this Agreement, we're going to stop global warming below the two degrees, or 1.5. Without it, the temperature will be increasing year by year. Now we are in a pathway to three degrees. But if we raise the level of ambition over time, we will be able to stop global warming below two degrees, and that's what the world needs.

PALMER: But the level of ambition to tackle, or even accept scientific concensus about the threat of global warming, seem to have evaporated in Washington since January this year. It was partly disappointment at new administration policies and an increasing sense of the dangers for the planet without action that brought thousands back onto the streets in 370 communities in the US and many more overseas for another Peoples’ Climate March on April 29th.

WHITE-HAMMOND: We are here because there is no Planet B. There’s no backup plan if we ruin this Earth that we have.

PALMER: The Reverend Mariama White-Hammond kicked off the rally in Boston with a message of urgency and unity.

WHITE-HAMMOND: No matter how many divisions there are across lines of race, religion, class, gender expression, immigration status. No matter how many divisions, we are bound together on this, one planet.

[AUDIENCE CHEERS]

PALMER: Health workers, vegans, faith groups, teachers, students, activists for employment and climate justice joined worried citizens to rally for an end to fossil fuels and raise the alarm about climate-related hazards that affect Boston and many coastal cities.

“C02 is like a bad relative that won’t leave… for hundreds of years” read one sign (Photo: Helen Palmer)

BAEHRECKE: We basically live on an ocean and we may not have a waterfront soon!

PALMER: There were the familiar hand-made signs. “Mother Nature says, ‘Cool It!’” and “C02 is like a bad relative who won’t leave for hundreds of years.” Even a dog named Ulysses wearing a sign that read, “Yo people! Stop with the carbon!" There were fiery speeches and music but overall a bleaker mood than the First People’s Climate March in New York in 2014.

LUCY: I mean, that march was just incredible. It was such an upswell of energy for the climate movement. Now there’s more of a fear that things won’t be heard, even though we’re speaking, but there’s more of a need even now I think than in 2014. There’s more of a sense that we’re up against something really big.

PALMER: Climate science hasn’t changed much in the last three years, but the political climate has undergone a sea change. The new administration is determined to roll back as many of President Obama’s climate actions as possible, including the Clean Power Plan, which underpins the US pledge under the Paris Agreement to cut carbon emissions about 27 percent by 2025. It’s uncertain whether the US will choose to keep that target or even stay in the Agreement. So, we may not always have Paris, an idea which upset some on Boston Common.

BAEHRECKE: If we pull out I think we’re crazy. We can’t afford to pull out because we’d send such a message to all the countries that are actually in the Paris Climate agreement.

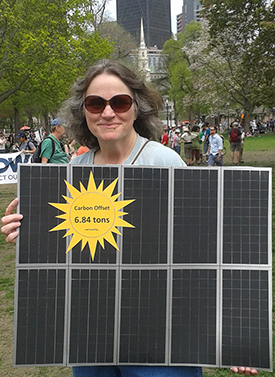

A woman at the march held a sign she made to represent her solar panels (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: But international opinion doesn’t seem to govern rhetoric or actions in Washington, and it’s one of the forces bringing people out onto the streets.

MILLER: When you listen to the news from Washington, there’s such a sense of powerlessness. Every day you can’t believe there’s yet another assault. So I think events like this, they’re really important in making you feel like, ok maybe alone, I don’t have any power but when I gather with my people, then I have some power.

PALMER: With views like that widespread, the recent pattern of record-breaking marches and rallies seems set to continue. As one popular sign reads: “The oceans are rising and so are we!”

[MUSIC: “DOWN BY THE RIVERSIDE” RECORDED ONSITE “I’m gonna fight for a greener world, down by the riverside. I’m gonna stand up for planet Earth.”]

Related links:

- The Washington Post: “The best signs from the People’s Climate March”

- The Boston Globe: “Thousands rally on Boston Common to demand action on climate change”

- The Washington Post: “In the Trump White House, the momentum has turned against the Paris climate agreement”

- LOE coverage of the 2014 march in New York City

Novel Man-Made Minerals

Fiedlerite, one of the newly catalogued mineral species, was discovered in an ancient smelting site in Greece, where slag met seawater. (Photo: Christian Rewitzer, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

PALMER: One of the big questions that currently concerns geologists is what epoch we live in, whether we’ve transtioned from the Holocene era, that began some 12,000 years ago after the last Ice Age, into a new age known as the Anthropocene, or the Age of Man. Now there are data that bolster the case for that transition, the discovery of some 200 new chemical compounds that did not, and could not, exist before the age of man. These new minerals were identified by Robert Hazen and a team from the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, DC, and the study published in the journal American Mineralogist.

Dr Hazen, welcome to Living on Earth.

HAZEN: So nice to be here, thanks so much.

PALMER: Now, Robert Hazen, one of the most engaging things about these new minerals that your team’s found is the names. Can you give me a few of them?

HAZEN: Oh my goodness. They're so whimsical. Bluelizardite named after the Blue Lizard mine, that's a great one. Widgimoolthalite. Can you imagine? That's from a place in Australia that I think very few people have visited. Of course, there are 5,200 names to remember here if you're a mineralogist. Most of us don't know them all.

PALMER: Now, as you say, there are about 5,000 naturally occurring minerals, and I thought chemistry had kind of finished, it had made all it was going to. What changed?

HAZEN: Well, you see, humans disrupt near surface environment. We dig mines. We have ore dumps. We have smelters. We have ships that sink, and then the artifacts on those ships get exposed to seawater that creates new kinds of crystals. That's why there are hundreds of minerals we think are human mediated. So, what happens when minerals form is that they are subjected to various physical, sometimes chemical, sometimes biological processes that help to rearrange those atoms into a new crystal structure. So, when you have a new combination of crystal structure and chemistry, that's a new mineral.

PALMER: So, what does a substance need to have to be considered a mineral? What's sort of special about it to make it a mineral?

All minerals, including this gypsum sample from a mine in Poland, are classified by their ordered, repeating molecular structure and their natural occurrence. According to Hazen, human-mediated mineral species represent something of a gray area because of their artificial origins. (Photo: Tjflex2, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

HAZEN: So, a mineral is special because, first of all, it's supposed to occur naturally and, of course, there's this grey area when humans get involved in the process. It has to be crystalline. That means it has to have the atoms arranged in a very regular, repeating pattern, and it has to have a chemical composition that makes it distinct. So, if you have that combination, then you have a new mineral, and there's something more than 5,000 of these recognized today on Earth. But, the fact that hundreds of them are arising because of human activities means that we have a pulse, almost the blink of an eye in Earth history unlike anything that ever happened before.

PALMER: So, does it have to be stable? Does it have to sort of like remain solid under certain circumstances, under, you know, a particular temperature circumstances or something like that?

HAZEN: You know, minerals just have to be crystalline, but some of them are very ephemeral. Ice, for example, is a mineral. It's water in a particular crystal structure. But there are other minerals that every time it rains, they disappear. I have a mineral named after me. It's called Hazenite. It is, I have to confess, microbial poop. It occurs in only one place in the world. That's Mono Lake in California, and it only occurs during the dry season. Every time the lake level rises or it rains, all of the world's supply of Hazenite disappears, only to come again when the microbes get busy making more Hazenite in the next dry season. People tell me, Hazenite happens. It's just one of those things.

PALMER: [LAUGHING] So, I don't think Hazenite is a particularly useful mineral.

The layers of rock in the Grand Canyon visually depict millions of years, and several different epochs, of mineralogical history. According to Hazen, humanity’s influences on the Earth mark a new, unique geological era. (Photo: Grand Canyon National Park, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

HAZEN: Well, it's not particular useful so far, but I guess the microbes like it, but it is definitely a biologically mediated mineral, and that's what the amazing things we’ve discovered, that more than two-thirds of almost 5,000 minerals require biology in one way or another. And so, these human-mediated minerals, this is just continuing this trend that so many of the mineral species are the result of biology.

PALMER: So, give me a few other examples of where biology comes in.

HAZEN: Well, biology comes in because photosynthesis, also as a byproduct, produces oxygen, and, when oxygen interacts with the surface environment, you get a whole range of new oxidized minerals. And then there are other minerals that are formed in the shells of clams and snails, in the teeth of sharks, and of course people. Bones, excrement, of all things. Tinnunculite is formed when falcons poop onto a burning coal mine, of all things. It's just almost inconceivable, but the burning coal mine basically refines the falcon poop and makes these little crystals which are minerals. They're naturally occurring minerals that form directly by biological processes.

PALMER: How do you feel about these discoveries? I mean, we've looked at nature as the master, but does it alarm you a little that suddenly man has become the kind of creator in this way?

HAZEN: Well, I think in a sense as someone who loves crystals and the diversity of crystals, it's rather marvelous to see. You know, at a time when we worry about biological extinction and a real decline in the variety of species of plants and animals, we're seeing this unprecedented explosion of new kinds of crystals. We're exploring nature in a way we've never been able to explore it before, and that's very exciting to me.

Robert Hazen is a research scientist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Geophysical Laboratory and a professor of Earth Science at George Mason University. (Photo: Carnegie Institute of Science)

PALMER: I was also reading that it may be the greatest sort of creation of new minerals since basically Earth became so oxygen-rich some 4.5 billion years ago.

HAZEN: Yes, indeed. This is the greatest punctuation event in the evolution of minerals. If you can imagine a future geologist, a hundred million years from now, a billion years from now, coming back to Earth, studying the various strata that have been laid down, perhaps going through a Grand Canyon-like structure that cuts through the strata of our time, you could see this rich layer with all of these unusual crystals. These are things that are going to persist for hundreds of millions of years, so, in a sense, humans are creating their own geological time strata.

PALMER: So, these new minerals obviously seem to me a powerful argument for the fact that we entered into the Anthropocene, the Age of Man. How does it seem to you?

HAZEN: Well, I do think that there's a very distinctive horizon of human-made crystals, unlike anything that’s occurred before in the 4.5 billion year history of Earth. Now, it's up to the stratigraphers, who are the official sort of guardians of nomenclature, to decide this, but it certainly seems to me that from a minerological point of you at least we’re in a new era of mineral evolution. That's very exciting to think about.

PALMER: Robert Hazen of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington. Thanks for spending the time with us.

HAZEN: Oh, my pleasure. Thank you so much.

Related links:

- The study in GeoScienceWorld: On the mineralogy of the “Anthropocene Epoch”

- About Robert Hazen

[MUSIC - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

Birdnote: Motherly Instincts

A female Peregrine Falcon with her young. (Photo: Ruth Taylor)

PALMER: If you’re out in your garden or the woods or by the water this time of year, it’s hard to miss the many birds, busy nesting and raising babies. But not all of them have strong maternal instincts as Mary McCann points out in today’s BirdNote.

http://birdnote.org/show/mother-birds

BirdNote®

Mother Birds

MCCANN: Motherhood. In the avian world, it’s a mixed bag.

Peregrine Falcon mothers share duties fairly equally with Peregrine dads. [Cakking of a Peregrine] Both incubate the eggs, although Mom usually spends more time at the task. For the first three weeks after the eggs hatch, she alone broods the young, and the male hunts to feed the entire family. When the young fledge, both parents feed them, and at the same time, teach the young birds to hunt for themselves. [Cakking of a Peregrine]

At the other end of the spectrum is the female hummingbird. [Wing-hum of a Rufous Hummingbird] She usually carries the entire burden of nesting, incubating, and tending the young, a true single mom. The male stays around, but only to protect his territory. He’s mostly a pest. [More wing-hum]

A diligent hummingbird mother. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

And then, there’s the female Western Sandpiper. [Chattering sound of Western Sandpiper flock] She finishes a nest the male has started, and they share incubation duties. But Mother Sandpiper usually leaves the family just a few days after the eggs have hatched. The male tends the young until they’re able to fly. It makes sense. The female needs to replenish herself. The eggs she laid almost equaled her body weight. [More chattering]

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Ellen Blackstone

Bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Peregrine Falcon recorded by G. Vyn. Hummingbird wing hum recorded by A.A. Allen.

Western Sandpiper calls recorded by Martyn Stewart, naturesound.org

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2017 Tune In to Nature.org May 2017 Narrator: Mary McCann

http://birdnote.org/show/mother-birds

PALMER: And for photos, flutter on over to our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

Listen on the Birdnote website

[MUSIC: Andrea Motis Joan Chamorro Quintet & Scott Hamilton, “Lullaby of Birdland” on Andrea Motis Joan Chamorro Quintet & Scott Hamilton, composed by George Shearing/arr.Joan Chamorro, SWIT Records]

PALMER: Coming up...the myths and mysteries of the tides. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Andrea Motis Joan Chamorro Quintet & Scott Hamilton, “Lullaby of Birdland” on Andrea Motis Joan Chamorro Quintet & Scott Hamilton, composed by George Shearing/arr.Joan Chamorro, SWIT Records]

Unraveling the Myths and Mysteries of the Tides

High tide and low tide at Crosby, Liverpool, where the human figures of the modern sculpture Another Place disappear twice daily under the rising water. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

PALMER: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Helen Palmer.

For the sailor, tide tables are a kind of bible that order your comings and goings. And mostly, sailors don’t stop to marvel at the heavenly powers that move the waters, even when they study the moon and stars on night passages. Now, there’s a book, "Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean", that melds science, history, and travel notes to explain the mystery of the tides, how humans have experienced and explained them, and what rising seas might mean for our relationship with our watery planet in the future.

Mariner Jonathan White was spurred to write the book when a tide caught him and his boat off guard.

WHITE: Well, I was actually in my mid 20s around that time when I got that big old wooden schooner, 65-feet. And we use to sail up and down the coast from Seattle to Alaska. And on one particular trip, we anchored in a small bay, and a gale blew up in the night, and I got up and noticed that something was wrong, and indeed we were aground at the end of the bay. We had dragged anchor.

PALMER: And what happened?

Jonathan White’s old schooner Crusader lists precariously as the tide rushes back in (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

WHITE: Well, I had been aground before, and if the tide was low, the boat would have come up, up off the mud, and no one would even have noticed. But as I studied the tide chart, I couldn't believe it because we were actually at the top of a high tide. And in Alaska they have large tides. So, what that meant was, in the next six hours, the water would go down 12 feet, and most of the water in this bay would disappear.

The boat went down and got stuck in the mud, so when the water came up it actually filled it with water, and by midmorning we were swimming through the boat. Everything started floating around. We had all provisions. Fruit and cookies and rice had swollen. We had a library of 300 books or so on the boat, and, if you've ever seen a book swell with water, you know that it gets three times the size and weight. It's actually a formidable weapon at that point. Some of the ironic titles that floated by that morning like, "Between Pacific Tides" by Ed Ricketts or "How Can I Help" by Ram Dass or "In Deep" by Maxine Kumin. It was quite funny at times.

PALMER: Long story short, you did in the end manage to get off, and you actually managed to refloat the boat and even restart the engine. But you're hardly the only mariner to go aground, of course. In the early days of exploration, there were many, many mishaps.

Author Jonathan White was inspired to write Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean following an experience when his schooner Crusader ran aground and flooded at the top of a high tide. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

WHITE: Oh goodness, eeven Cook in his explorations went aground in Australia in a very famous grounding where the tide went out and left them high and dry and, of course, they were used to very different tide regimes and didn't understand the dynamics of the tide in Australia which is typical of those days. The people were familiar with what happened around where they lived, but, once they went afar, they were quite often surprised. Where England and here has two tides today and, in fact, on the Atlantic coast as well, many, many places around the world have that. There are places like Tahiti that has one tide a day, and there are places that have four tides a day, and there are places that have six tides a day, and there are standing tides and double low tides and double high tides. So there are lots and lots of anomolies.

PALMER: Well, we all learn in school that basically it's the moon's influence that makes the tides. So, can you tell us how it is that the moon makes the tides happen?

WHITE: Yes, I'll start by saying it actually is the moon and the sun, but the moon because it's so much closer has about 50 percent more influence on tides. When the sun and the moon are working together, as they do during full moon and new moon, that's when we have our largest tides. But when the moon and the sun are at 90 degree angles to each other relative to the Earth, that's when the moon and the sun are working against each other, and we have the lower tides. It's called the neap tides.

So, when the moon is overhead and full, it's creating a bulge in the Earth's oceans underneath it, and we are actually spinning underneath that bulge. That's really how it works. There's a bulge facing the moon, and then here's another bulge on the opposite side of the Earth that's created by centrifugal force, which is the force we all experience when we come around a swerve driving, and what we feel is that the car wants to straighten out or flip over. Right? Well, that's generally why we have two tides a day.

Fishing boats at high and low tide in the Bay of Fundy, where the tidal range is a whopping 54.6 feet. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

PALMER: You spoke about the Earth spinning, and, indeed, as well as the sun's influence, there are also more influences of more weird phenomenon, like the fact that the Earth wobbles on its axis and, obviously, at some stages the moon is closer to us, and at some stages it's further away. All these play into the tides, which is why it becomes so complicated.

WHITE: Yes, that right. It's important to remember that everything is moving, and there's a gravitational relationship between all these parts. In general, there are over 400 of these relationships that affect the tide.

PALMER: Wow. You made me familiar with some wonderful words like “perihelium” and “perigee,” and my favorite of all is this word “syzygy.” S-Y-Z-Y-G-Y. It's wonderful.

WHITE: Yes, it's a great Scrabble word. It's a Greek word meaning “yoked together,” and it describes when the Earth, moon and sun are aligned. So, when we have our largest tides, it's usually because the Earth, moon and sun are aligned, and that's called syzygy.

PALMER: As I say, it's a great word.

You write about the vast differences in height between low and high tides, in some places as much 54 feet, yet the discrepancy is only about a couple of feet in, say, the Mediterranean. How does that come about?

WHITE: Well, the tide is a lot of different things, but you can boil it down to vibration and resonance, and resonance when something vibrates in response something else. So, when we talked about these four hundred different relationships from the heavens, right? Well, that's what's happening up there. What happens down here, is in a sense, the ocean basins of the world hear these relationships as if they were notes or beats or pulses, and the ocean basins, each one has a different kind of characteristic that responds to any one of those notes or calls from the heavens in a different way, and that's called resonance.

PALMER: Talking of the resonance in the ocean, you have a wonderful description of how they all interact with each other.

WHITE: Yes, I was walking through Oceanographic Institute with an oceanographer in the Bay of Fundy, a man named Charlie O'Reilly, and he said, "Well, it's like having a table, and if you fill the table with pans, all different sizes, shapes, some deep, some shallow, and then fill them with water e,ven at different levels, some all the way up, some just low, and then if you start kicking the table with the rhythm, right, and that kicking by the way is a force from the heavens. You know, again, it might be the full moon. And those pans will respond differently to the kicking. Some pans will be very excited, and some pans not so much. And then, you also have to remember, because they're touching, they also influence each other.

Low tide and high tide at Perranporth, Cornwall in the U.K. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

PALMER: It's a wonderful image because obviously you realize that the tide comes in and then it bounces off the shore and then maybe it hits another, maybe an island or it hits a reef or it hits the next continent.

WHITE: Yes, absolutely. There are vibrations that happen in Europe that find their way over, you know, thousands of thousands of miles, and they show up on another coast. That is absolutely true. The tide, you know it's a large wave that travels at 450 miles per hour around the Earth. When it hits continents, it reflects. It refracts. It folds back on itself. It slows down. It speeds up. I mean, it's mind-boggling how complex it gets.

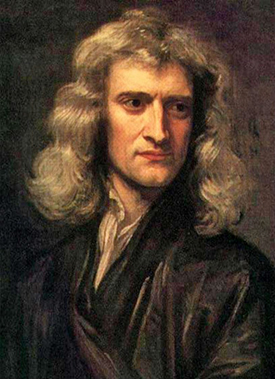

PALMER: In your book, you write about the many scholars throughout history from ancient times who’ve tried to unravel these mysteries. How did the Enlightenment change our understanding of this given that this goes back to the Greeks and, indeed, I presume, to the Phoenicians and Babylonians too?

WHITE: Yes, for most of human history, 99 percent of human history, we had a very, very different view of the heavens. Right? We obviously observed it and, in fact, the earlier observers were called priests or astrologers, and they kept very precise information about the relationships of what was going on up there, eclipses and so forth, but they didn't know how it worked. They might look up at the moon and wonder, how does she do it? How does she reach out silently and invisibly over all that distance and stir the waters of the Earth?

Sir Isaac Newton’s law of universal gravitation radically changed human understanding of the tides (Photo: Sir Godfrey Kneller, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

I mean nobody knew this. Right? But they speculated. I mean, some people thought the moon did it by heating rocks on the bottom of the ocean, and when those rocks were really hot, the water would boil and swell and that was high tide, and then when the moon went away those rocks cooled and that was low tide. And some people thought it was the breathing of a large beast or the breathing of the Earth itself. Even Leonardo da Vinci in the 13th century thought that it must be the breathing of a large beast, and he tried to calculate the size of its lung. Yeah, and on our coast, actually just up the coast where I am, High Tide Woman made the high tide by lifting her skirt.

And then, during the scientific revolution, culminating with Newton, we really radically changed that view of the heavens because gravity, until then, was just an inherent nature inside any object or person that caused it to fall. In fact, Keppler, the German scientist, said, “Gravity is soul. It's the soul of something that makes it want to go back to Earth.” It was the soul of the apple that made it want to fall.

And of course Newton changed all that and gave us the laws of planetary motion and gravity, and, again, that's when we started to get our foothold. But even Descartes, who is of course a French philosopher, a natural historian, they wanted to get away from gravity. You know, these new scientists wanted to leave the ancient world behind, and they couldn't stand the idea of gravity because it was this black magic, invisible force that did not fit with the new world, but in the end they reluctantly had to plunk it in the middle of their theory.

PALMER: Well, I have to say that gravity is still so mysterious that I can believe that there's a woman who lifts her skirts and that's how the tides come and go, just as easily as I could believe in gravity.

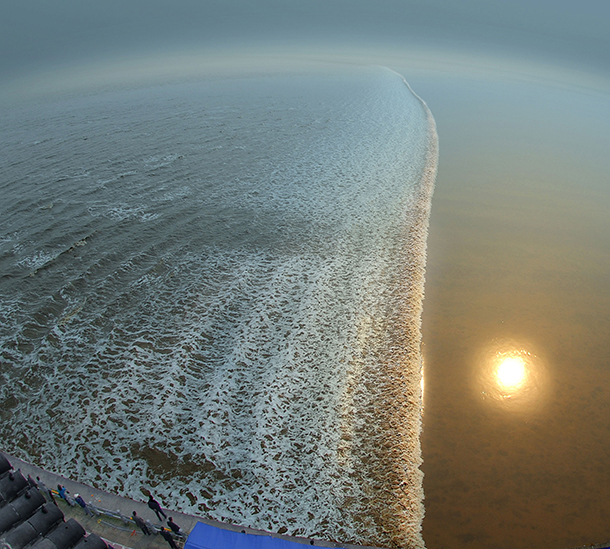

The tidal bore on the Qiantang River is known as Yin Long (Silver Dragon). (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

WHITE: Yeah.

PALMER: So, your book is quite a travelogue and an adventure story, quite apart from going aground. You follow surfers in search of monster waves, and you go in search of tidal bores. Tell me about tidal bores and the one you watched in China.

WHITE: Yes, that's a tidal bore on the Qiangtang River. And a tidal bore is when the tide comes up the river in the form of a wave or a solid wall of water. There might be 100 of them around the world, in the Bay of Fundy, up in the Cook Inlet in Alaska. The Amazon River has a large one. But the tidal bore on the Qiangtang River in China, which is just south of Shanghai in Hangzhou, is the largest in the world. It gets up to 25 feet tall, and it comes in on every tide, twice a day, every day. The first tide chart in the world that we know of came out of that place, and it was to log when the tidal bore showed up, and it was etched in stone in the 10th century, and it was probably a couple of hundred years before the first tidal chart appeared in the west, for the London Bridge in 1200.

PALMER: You've talked about these great tides, and I was actually struck that people in the past have used tides for power. I'd like you to read a passage from your book, please, if you wouldn't mind. It's on page 230. Can you explain the context for it?

WHITE: Yes, I think that people don't often realize how long we've been using tide energy actually. There were thousands of them around Europe, and on the east coast of the United States, particularly in the northern part there, we had hundreds of tide mills that started around 1620 and lasted all the way through the mid-1800s, milling lumber, and making paper, and fashioning copper.

And there is one tide mill, the oldest in the world, that is south of London in Southampton, actually, in the village of Ealing that is still operating. They still make flour. And I went there, and I got lucky. One of the tide millers invited me to help him with a tide cycle. And so, that's the context for this piece of writing.

[SOUND OF THE PAGE OF A BOOK TURNING]

The Eling Tide Mill building, with an old mill stone in the foreground and the tidal barrage (the wall with buttresses) visible. (Photo: Colin Babb, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 2.0)

“Laboring at first, the wheel eventually rumbled to speed. The whole place seemed to come alive, creaking and groaning like a ship at sea. Windows shook. Iron latches and levers rattled. A spoon and pencil chattered in a jam jar. Upstairs, the grist bin’s tick-tick-tick confirmed that grain was being fed to the grinding stones. When I looked up from the swishing and gurgling water wheel, a stream of golden flour was pouring from the chute. The water wheel ran for four-and-a-half hours. Through the windows, I watched the tide disappear from the harbor, leaving all the boats aground. The mills wheel-wash gushed into the estuary like a whitewater rapid. A fine powder had the filled the air as soon as we started producing flour, settling on everything including our eyebrows and eyelashes. The place smelled like baking bread, hot grease, and low tide.”

PALMER: It's a wonderful bit of writing. It's wonderfully descriptive.

Finally, we know that sea level is rising due to global warming, so what can we expect from the tides in the future, or do we just not know?

WHITE: There's a lot of that we don't know, but we do know that, if sea level rises three feet in the next 50 years, which is a conservative estimate, there will be a lot of people and communities that will have to move. And I think one the things that is important to understand is that sea level isn't level. I mean, we're taught in kindergarten that water seeks its own level, and it may, but it doesn't find it in the ocean.

For example, where I live on the Pacific, the trade winds push the water across the ocean westward and it piles up in Asia, in the South Pacific. So, that level over there is two feet higher than it is against my coast, and the Pacific is about a foot higher than the Atlantic, and the Atlantic slopes from Florida up to New England. Also, we know that land is changing. Right? Some land is rebounding from the last glacial age, lifting, and some land is sinking. The tides happen on top of all that. And, if we harken back to that conversation about resonance, as the sea levels change, it changes the basin's natural frequency of vibration. So that's where we're going to have the major changes in tides, and we could see larger tides in some places, and, in fact, we could see lesser tides in others, as sea level rises.

Author Jonathan White is an avid surfer and sailor. (Photo: Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean)

PALMER: Jonathan White is a marine conservationist, sailor, surfer and author of the book "Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean". Thanks very much for spending time with me today.

WHITE: Thank you, Helen. I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean

- LiveScience: “What Causes the Tides?”

- Eling Tide Mill

- NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Tides & Currents

- How modern tidal power works

[SOUND OF BARKING FROGS, BIRDS]

PALMER: We leave you this week lost among the maples.

[SOUND OF BARKING FROGS, BIRDS ]

PALMER: Lost Maples State Natural area in the Texas Hill country protects a stand of Uvalde sawtoothed maples noted for their fall colors, but not for barking.

[SOUND OF BARKING FROGS, BIRDS ]

PALMER: That’s Craugastor Augusti, the barking frog of the Hill country. It breeds in damp earth under boulders or in rock crevices and the eggs hatch into tiny frogs, without a tadpole stage.

[SOUND OF BARKING FROGS, BIRDS ]

PALMER: Lang Elliott recorded these barking frogs at Lost Maples as part of his Music of Nature Soundscape trip in early March this year.

[MUSIC: Project Trio, “Djangish” on Instrumental, Project Trio Records]

PALMER: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe/Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. This show was edited by Thurston Briscoe. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Helen Palmer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth