November 13, 2015

Air Date: November 13, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Climate Movement Post Keystone

View the page for this story

President Obama has struck down the tar sands Keystone XL pipeline and many suggest that’s partly politically motivated and partly in response to the environmental demand to “Keep fossil fuels in the Ground.” Host Steve Curwood and Michael Brune, Executive Director of the Sierra Club, reflect on the defeat of the Keystone XL pipeline, the need for civil disobedience, and what’s next for the environmental movement domestically and as the world heads to the UN’s Paris climate talks. (10:35)

A Demand for a Green Transition

/ Derrick JacksonView the page for this story

Recent decisions to end fossil fuel extraction, including Shell’s drilling hiatus in the Arctic and President Obama’s veto of the Keystone XL pipeline are offset by new permits in the Arctic. Commentator Derrick Jackson argues that the US must make climate change a priority and act swiftly and responsibly to be a leading climate change activist that the world needs. (03:00)

Infrared Technology To Cool Buildings

/ Jake LucasView the page for this story

The US Department of Energy estimates that air conditioning consumes nearly fifteen percent of energy used by buildings. Now, as Living on Earth’s Jake Lucas reports, a group of Stanford physicists and engineers have developed a technology to keep buildings cooler by reflecting sunlight as infrared radiation out into the coldness of space from the building’s roof. (01:55)

Big Battery Breakthrough

View the page for this story

Expensive lithium-ion batteries fall flat when it comes to storing and discharging large amounts of energy. Last year, Harvard scientists developed a flow battery that stores energy in vats of inexpensive chemicals. Now they’ve improved upon this design with a battery that’s non-toxic as well as cheap and scaleable. Host Steve Curwood tours the lab with inventors Professor Michael Aziz and Roy Gordon and graduate student, Kaixiang Lin. (10:25)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s episode, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about responsible reporting on possible safety concerns of water-saving artificial turf, and the effort to squeeze fresh water from the sea. Then, a trip way back into history to another discovery we can “thank” Columbus for: tobacco. (04:45)

Building a Better Honeybee

/ Lou BlouinView the page for this story

Bees are vital for our food system because they pollinate so many fruits and vegetables, but disease, pests and new insecticides have hit them hard. So a group of beekeepers and researchers are breeding a honeybee that can better resist destructive mites that weaken colonies. Lou Blouin of the Allegheny Front reports. (05:00)

The Beekeepers of Ancient Egypt

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Professor Gene Kritsky of Mount St Joseph’s University is an entomologist, but his latest book is a historical look at beekeeping in ancient Egypt. Professor Kritsky discusses honey, hives, and hieroglyphs with Living on Earth’s resident beekeeper Helen Palmer. (12:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Brune, Michael Aziz, Roy Gordon, Gene Kritsky

REPORTERS: Jake Lucas, Lou Blouin, Derrick Jackson, Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer

[MUSIC: THEME: Boards Of Canada, “Zoetrope,” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country,” (Warp Records)]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Activists cheer the decision to reject the Keystone XL pipeline and say it will have a practical as well as a symbolic effect here at home and at the upcoming climate negotiations in Paris.

BRUNE: It will dramatically slow down the rate of growth in the tar sands, but it's also important because what it says is that our movement has become so strong that we're beginning to stop carbon pollution at its source.

CURWOOD: Also, beekeeping in the age of the pyramids. To ancient Egyptians, bees were sacred because the sun god Re created them.

KRITSKY: The god Re wept, and the tears from his eyes fell on the ground and turned into a bee. The bee made his honeycomb and busied himself with the flowers of every plant. And so wax was made, and also honey, out of the tears of Re.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In a Beautiful Place Out in the Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[MUSIC: THEME: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In a Beautiful Place Out in the Country” (Warp Records)]

The Climate Movement Post Keystone

TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline would have carried 830,000 barrels of oil per day. (Photo: shannonpatrick17, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. President Obama’s recent rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline to transport tar sands crude from Alberta to Gulf coast refineries marks the end of more than six years of review, and years of mass protests and arrests of campaigners right at the White House. Delays ultimately made Keystone XL less important to the oil industry, along with the lower price of oil, more oil trains and the conversion of other pipelines, though industry fought hard, often through Republican members of Congress, to keep Keystone alive. But the pipeline’s rejection is seen as a huge victory to the movement activists have dubbed “keep it in the ground,” words President Obama echoed when he announced his decision November 6th.

OBAMA: Ultimately if we're going to prevent large parts of this Earth from becoming not only inhospitable but uninhabitable in our lifetimes, we're going to have to keep some fossil fuels in the ground rather than burn them.

CURWOOD: Sierra Club Executive Director Michael Brune was one of the hundreds of climate campaigners jailed during the wave of demonstrations, and he joins us now. Michael, welcome back to Living on Earth.

BRUNE: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: Now, how do you, your club members and other activists feel now about Obama's decision to block Keystone?

President Barack Obama talks with Vice President Joe Biden and Secretary of State John Kerry outside the Oval Office prior to entering the Roosevelt Room to announce the administration's rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline on Nov. 6, 2015. (Photo: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

BRUNE: We're all thrilled. This is one of the biggest victories in the environmental movement in the last several years, in part because it means that'll be very difficult to expand development in the tar sands, but also because this is the first victory in what will be a long-term campaign to keep more fossil fuels in the ground, more oil, more coal, more gas in the ground rather than extracting and burning them which is, of course, a big part of the fight against climate change.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, much of the Alberta tar sands oil, even given the reduced price of oil, it's still getting to market. What do you say to people who suggest that the victory was more symbolic than substantive?

BRUNE: Well, it's not true, and I know that for a fact because when I talk to the oil industry candidly and off the record they will tell me as much. Here's what's happening in the tar sands. They produce about two million barrels of oil a day, much of which is sent down into the United States. The tar sands is landlocked and they are almost at capacity. They need more access to markets in order to grow. The Keystone XL pipeline would've dramatically expanded extraction from the tar sands and now that has been taken off the table. It is not profitable for the oil industry to ship large amounts of tar sands crude by rail. It's also dangerous. It's highly expensive. So this victory is important because it will dramatically slow down the rate of growth in the tar sands, but it's also important because what it says is that our movement has become so strong that we're beginning to stop carbon pollution at its source.

CURWOOD: In your view, how powerful is the climate movement that we have today and how important was Keystone as the galvanizing fight for that movement?

BRUNE: Well, the Keystone fight has been a big part of the environmental movement particularly in North America for the last five, six, seven years. But it's really just a part of the movement. We have become big enough and broad enough that we have seen tremendous progress on a number of fronts. Just to give an example, the same day that the president announced that he was rejecting Keystone, we also celebrated the announced retirement of the 206th coal fired power plant in United States. That progress has helped the United States to cut its carbon pollution by 18 percent, which is more than any other country in the world. So the victory in the tar sands is coupled with the victories that we've seen against coal plants in the US, the progress that we're seeing on clean energy across the country and around the world, and I think it gives a reason for hope that we actually were up to the task as a country and as a species at actually being successful in fighting climate change.

CURWOOD: What did you make of the president's use of the phrase "keep it in the ground"?

Senators Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) introduced the Keep It In the Ground Act on November 4, 2015. (Photo: office of Sen. Jeff Merkley)

BRUNE: Well, it was one of the more satisfying phrases I've ever heard the president say because we have been fighting for years in the climate and energy space, and most of the work that we have been doing has been on the demand side, making our cars and trucks more fuel-efficient, cleaning up power plants, tackling pollution at the smokestacks. All of that is strong, it's effective, but what we really need to do is to couple that with a supply side strategy. So the president implicitly acknowledged that. He says we have to keep some dirty fuels in the ground rather than burning them, and this represents a great victory because what it will mean in the future is that the Obama climate test can be applied to other energy infrastructure projects. For example, should we expand a coal mine in Utah right next to adjacent national parks that not only will contribute to haze in our national parks but also it will make climate change, much, much worse. That kind of test about whether we should even extract fossil fuels in the same quantities, is a groundbreaking moment for US energy policy and it's a great victory for climate activism around the world.

CURWOOD: So, I'm thinking back to September when there were protests at the White House demanding that President Obama halt the attraction of fossil fuels from federal lands and waters, and just recently Senators Jeff Merkley, a Democrat from Oregon, and Bernie Sanders, the independent from Vermont who's running for president, introduced what they call a "keep it in the ground" act which would block new leases for offshore drilling and fossil fuel development on public lands. Michael, to what extent is keep it in the ground going to be the new rallying point of the climate activism movement here in the US now that Keystone is now, well, moving towards history books?

BRUNE: I think it'll be a big part. To be clear, there's lots of things happening at the same time but this is what is new and this is something that's really exciting to a lot of people, the idea that we can grow our economy, we can create jobs, we can increase prosperity by transitioning our economy to clean energy. We don't have to expand mining on taxpayer owned lands when solar and wind will do a better job. We don't have to frack or drill for oil and gas on, again, public lands when we know that investing in energy storage, advanced batteries, electric vehicles will create more jobs, it'll clean up our air and water and it will stimulate our economy even more.

The Keep It In the Ground Act would prohibit all offshore drilling in the Arctic and the Atlantic Ocean. (Photo: Robert Seale/Maersk Drilling, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: How likely is it that "a keep it in the ground act", a law cutting off fossil fuel extraction for public property could get through this or even the next Congress do you think?

BRUNE: I'm very hopeful for this strategy. I think that what you'll see over the next few years is an increased level of engagement from federal agencies, so the Department of the Interior in particular, but also the Department of Energy, Department of Agriculture, the White House itself, that begins to look at new coal, oil and gas proposals, new leases, with an increased amount of skepticism and in terms of a bill being passed, we have an obvious obstacle right now in which much of the Republican Party doesn't even acknowledge that climate change exists, rarely acknowledges the economic benefits of clean energy, and we have to find a way to break through that.

CURWOOD: Back in the civil rights days, the sit-in at a particular lunch counter that resulted in arrests and perhaps the desegregation of that lunch counter didn't guarantee that other lunch counters were going to be desegregated. People had to go to jail again and again and again. Given the length of time it might take from Congress to get its head wrapped around this, how soon are you planning to get arrested to protest the leasing of federal lands from fossil fuel extraction and when do you think the new phase of this movement catches fire?

Michael Brune was arrested in front of the White House on February 14, 2013 along with 47 other environmental, civil rights and community leaders who demanded that President Obama reject the Keystone XL pipeline. (Photo: Christine Irvine/tarsandsaction, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BRUNE: Look, I will engage in peaceful civil obedience anytime that I think it will be effective at accelerating our transition to a clean energy economy. So if I need to participate in civil disobedience to protect the Red Rock Canyons of Utah or to stop fracking in California or to show that clean energy will do a much better job, then I'm happy to participate in that. A couple years ago, I was with my wife and our kids on the National Mall in Washington DC, and at the American History Museum there was a display of the Woolworths counter where some of the first sit-ins took place at the civil rights museum. And I remember my daughter was about seven years old at the time, and I talked with her about the civil rights movement and the fact that African-Americans were not allowed to sit at the lunch counter and buy lunch, and she thought that that was insane. She thought it was absurd. She couldn't believe that people would have to get arrested to protest the law that was so unjust. And I think that if you look at where we are today in 2015 it is crazy that we are fracking in our watersheds and near our national parks. We are so dependent on fossil fuels that it threatens the stability of our climate, and if it takes civil obedience to accelerate the rate at which we're addressing this problem or to advance solutions, then it is an easy decision to participate in such an action, and I would be proud to do so on behalf of the Sierra Club once again.

CURWOOD: Looking ahead now to the climate summit that opens in Paris at the end of this month, how important do you think the President's rejection of Keystone was for US credibility at the negotiating table there?

Brune says that President Obama’s rejection of Keystone XL, just weeks before the Conference of the Parties in Paris, shows that the U.S. is serious about ensuring that some fossil fuels stay in the ground. (Photo: Arnaud Bouissou/Le Centre d’Information sur I’Eau, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

BRUNE: The president's rejection just a few weeks before the climate summit opens in Paris is critical. It shows that the US is committed, that we are sincere, and we are unwavering in our determination to not just hit the goals that we've set out in this country to cut carbon pollution, but that we expect to exceed those goals and lead other countries around the world in transitioning to clean energy. The president has taken a lot of actions over the last seven years to make our cars and trucks more fuel efficient, to replace dirty coal plants with clean energy, but his announcement on Keystone shows that he's also willing to take actions to make sure that fossil fuels stay in the ground, and that is a huge victory for what were trying to achieve in Paris.

CURWOOD: Michael Brune is the Executive Director of the Sierra Club. Michael, thanks so much for speaking with us today.

BRUNE: Thank you, Steve, it's good to talk to you again.

Related links:

- Michael Brune’s post: “The Pipeline Stops Here”

- What critics of the Keystone Campaign misunderstand about climate activism

- Bernie Sanders and Jeff Merkley have a new bill to leave fossil fuels in the ground

- Keystone’s Dead. Here’s What’s Next on the Enviros’ Hit List

- Keystone Pipeline May Be Big, but This Is Bigger

A Demand for a Green Transition

The Bureau of Land Management recently approved a drilling permit for oil and gas extraction in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska. NPR-A is the largest single block of public land in the U.S. and is home to caribou and other wildlife. (Photo: Bob Wick/BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, the President’s decision to nix the Keystone XL pipeline comes against the backdrop of somewhat contradictory moves by his Administration when it comes to fossil fuel policy. And those contradictions set commentator Derrick Jackson thinking.

JACKSON: Actions at home give hope that the United States finally intends to be a world climate leader abroad. Last month, the Obama administration canceled Arctic offshore oil leases through 2017. This was after Shell gave up operations in the Chukchi Sea having blown $7 billion to find very little oil.

Then came the decision by the president to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline because, he said, approving it would have “undercut” America’s leadership to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and we must leave some fossil fuels in the ground.

To be sure, the administration’s decisions are mixed. Shell’s arctic cancellation actually bailed out the White House, which approved the drilling as part of its “all of the above” energy strategy; a strategy that included a recent oil and gas-drilling permit on Alaska’s national petroleum reserve. Despite the reserve’s ecological significance for caribou, migratory birds and grizzly bears, the government says the new operation will "provide additional economic security for Alaskans as well as a new source of oil for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System.”

That came as sort of a consolation prize for Alaska Governor Bill Walker. With native coastal communities losing land to rising seas, Walker recently claimed that the best way to pay to relocate those villages is to drill for more oil. In a state with no sales or income tax that derives 90 percent of its revenues from oil, Walker knows only one way to generate cash - Drill Baby Drill.

Such thinking is now trumped by the urgency of climate change. As Obama said in canceling Keystone, it is time to put aside the old rules that America cannot promote economic growth and protect the environment at the same time. He boasted that the nation’s transition to a clean energy economy is happening faster than many anticipated. But he and his successor in the White House could accelerate that transition by going further.

Not only should the pause on offshore leases become a permanent prohibition, the government should give out no new permits in Alaska, the Atlantic or on any public lands. The nation should instead accelerate its investments in solar and bring on line more projects such as the newly proposed 100-turbine offshore wind farm south of Martha’s Vineyard.

The United States, with its massive environmental footprint, is late to the game on climate change. But it is not too late. With the decisions on Arctic oil leases and Keystone, this nation is finally becoming the big foot it needs to be in Paris.

CURWOOD: Commentator Derrick Jackson.

Related links:

- Obama Sticks a Fork in Arctic Offshore Drilling

- Citing Climate Change, Obama Rejects Construction of Keystone XL Oil Pipeline

- BLM approves drilling permit in Alaska petroleum reserve

- The ecological significance of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska

- The impact of climate change in Alaska

- European firm pitches huge wind farm off Martha’s Vineyard

- About essayist Derrick Jackson

[MUSIC: R. Carlos Nakai, Kokopelli Wind, Canyon Trilogy (Canyon Records)]

CURWOOD: Just ahead, finding a cheaper way to boost green power. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: AC/DC, Live Wire, Angus Young/Malcolm Young/Bon Scott, High Voltage (Epic Records)]

Infrared Technology To Cool Buildings

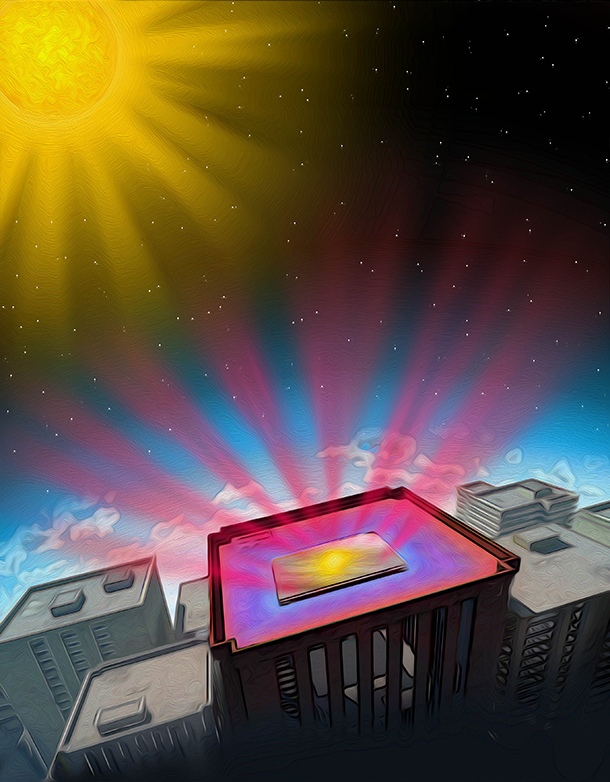

An artist’s rendition of the sky cooling system in action. (Photo: Nicolle Fuller, SayoArt LLC)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In a minute, a possible key to storing vast amounts of renewable energy, but first this note on emerging science from Jake Lucas.

LUCAS: The Department of Energy estimates that almost fifteen percent of the energy US buildings used in 2011 went to powering air conditioners. As the climate warms, that percentage is likely to grow.

The experimental system on a sunny roof in Stanford, California. (Photo: courtesy of Aaswath Raman)

So there’s an urgent need for less energy-intensive ways to keep buildings cool. And now, a team of Stanford physicists and engineers has developed a system that uses the infinite cold of outer space to do just that.

Their set up is designed to sit on a building’s roof and emit infrared light primarily within a specific range of wavelengths. That allows the light to pass through a sort of infrared light window in the atmosphere. The system is made of alternating layers of hafnium dioxide and silicon dioxide, some thicker, some thinner. Differences in how light passes through those two materials and their varying thicknesses allow this invention to emit infrared light without absorbing very much of it, which would heat up the system.

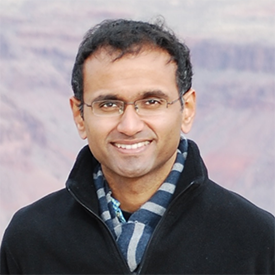

Aaswath Raman, lead author of the group’s paper. (Photo: courtesy of Aaswath Raman)

The Stanford scientists are not the first group to do this, but what makes their set up unique is that it’s pretty cheap to make, and it reflects sunlight, so it works during the day. In fact, in direct sun, their system was able to cool the air by nearly 5 degrees Celsius, about 9 degrees Fahrenheit. And, they say there’s still room for improvement.

One lingering question is how to get a building’s heat through floors and insulated ceilings to the system on the roof, but the group from Stanford is working on that too. And once they figure it out, they say their set up could lend a much-needed hand to all those air conditioners. And that is pretty cool.

That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. For Living on Earth, I’m Jake Lucas.

Related links:

- The group’s paper, published in Nature

- About Aaswath Raman, the paper’s lead author, and his research on sky cooling

- The Ginzton Lab at Stanford, the group behind the research

- The DOE’s data book on buildings’ energy use in 2011

- Research review on other low-energy, or “passive”, cooling techniques like the Stanford group’s

Big Battery Breakthrough

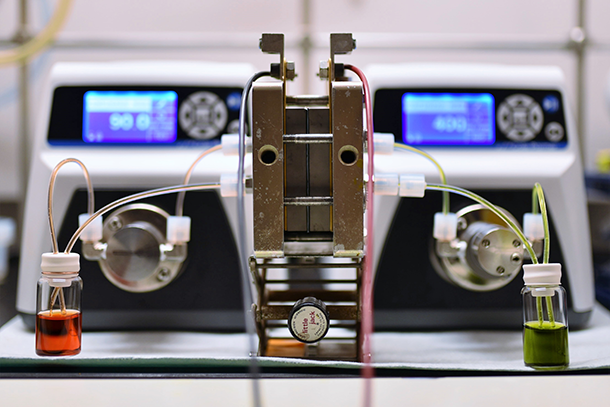

The alkaline quinone flow battery (Photo: Kaixiang Lin)

CURWOOD: The UN climate talks in Paris at the end of this month give the world a chance to craft a meaningful treaty to control global warming gas emissions. Wind and solar have huge potential, but since the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow the big hurdle in expanding the use of renewables is the lack of cheap and efficient storage of that energy. That could be about to change. Breakthroughs in the technology of what are called mega-flow batteries would seem to make them commercially viable in the near future. To find out more, I went to visit a couple of senior academics at a university near our office.

AZIZ: I’m Michael Aziz, the Gene and Tracy Sykes professor of Materials and Energy Technologies in the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

GORDON: I’m Roy Gordon, I’m the Cabot professor of Chemistry and Materials Science in the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

CURWOOD: Roy Gordon has a string of patents to his name for developing various electro-chemical and thin film technologies used for such things as semiconductors, solar cells and advanced window insulation, and he likes to be on the frontiers of science and technology.

GORDON: I’ve been working on energy technologies for decades, but now that these renewable sources are becoming more widely used, the storage issue has become front and center.

CURWOOD: But a battery that would really work needed the input of an energy-systems expert like Michael Aziz – who also has a few patents, including ones for flow batteries to solve the problems of the ones we usually use.

AZIZ: Think about running your home on the electricity from your rooftop solar panels that you get during the day. You need to be able to run that battery for hours before it’s drained. Traditional solid electrode batteries are drained within an hour. If you want more energy, you can stack up banks and banks of batteries, but you’re paying not just for the engineering to give you the energy and the materials that give you the energy, you’re paying for the engineering to give you extra power you don’t need. As a result, traditional batteries are just way too expensive to be used this way.

CURWOOD: To address this inefficiency, professors Aziz, Gordon and their colleagues set out to develop an inexpensive megaflow battery, and they think they’ve come up with a way to make them safe as well as commercially viable. Expensive flow batteries using precious metals like vanadium have been around for years. They separate the energy storage from the electrode interface that releases or charges the battery, by using separate tanks of positive and negative electrolytes—chemicals that can store and transmit electricity.

AZIZ: The advantage of the flow battery idea is: you can design the cell—the area of the electrodes—for just how much power you need and no more, and then you can get more and more energy with just bigger and bigger tanks full of chemicals. If the chemicals are cheap, then you have a winning proposition for much lower cost storage of intermittent, renewable electricity for long-duration discharge.

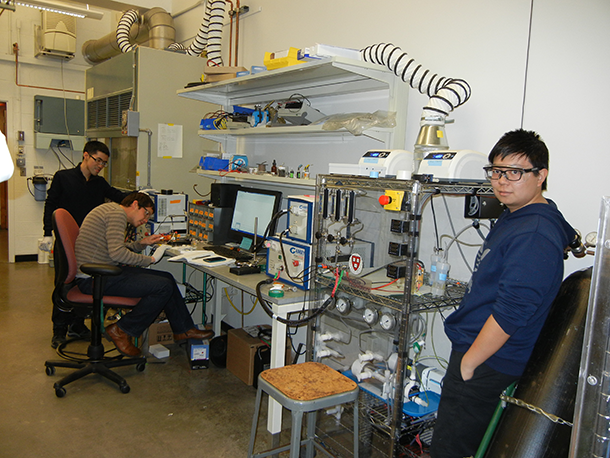

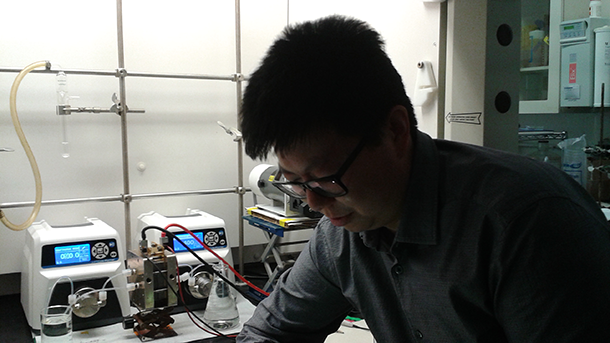

CURWOOD: To see how this team’s latest flow battery works, we headed off to the lab to see it in action.

[WALKING DOWN HALL AND INTO LAB]

CURWOOD: There we found one of the students working on the project.

[DOOR]

CURWOOD: Can I ask your name?

LIN: My name is Kai Xiang. I’m a third-year graduate student from Professor Roy Gordon’s lab. I’m doing the synthesis of the electro-active molecules, but I’m also doing the electrochemical studies on those molecules as well in Professor Aziz’s lab.

LIN: So this is the flow battery setup. We have five central components here: so we have two pumps, and two reservoirs, one for the negative electrolyte, one for the positive electrolyte. And the pump basically pumps the electrolytes into the electrochemical cell where the electrochemical reaction takes place, either to charge the species or to discharge the species to get the electricity out. So, one of the benefits of the flow battery is that we can change the energy of the battery. For a laboratory test, we use as small volume as possible. I’m using like 5mL of the electrolyte, but you can change that to however you want it based on the need of the application. So the energy of the battery is really arbitrary.

AZIZ: The system we’ve got here has a power capacity of only a couple of watts, and to go to the home storage scale, you need something a thousand times more powerful. To go the utility scale, you need something another thousand times more powerful.

[WALKING BACK TO OFFICE]

CURWOOD: Last year this Harvard team figured out one could replace the precious vanadium-based negative solution with a Quinone, a chemical compound fairly similar to one found in rhubarb. But back in the office Professor Gordon told me there was a problem with the chemicals on the positive side.

[OFFICE ATMOSPHERE]

GORDON: The other side of the battery used last year in our lab is based on bromine. Bromine is a toxic and corrosive material, so that’s not something that you’d want to have in tanks in your basement. But we replaced that with a new chemical that is much safer; it’s actually a food additive: ferrocyanide. Now, cyanide sounds scary and dangerous, now, this is not poisonous. So, we think this is safe to have in your home or your basement or your neighborhood.

CURWOOD: But there was still a problem. This safer chemical for the positive side prefers an alkaline, rather than the acidic environment that was used for the earlier battery. But it didn’t take long, said Professor Aziz, for another member of the team to find answer. The post-doc that was working on the project, Mike Marshak, now an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at the University of Colorado, he noticed that the quinones could also be made to be soluble in alkaline solution and that opened up the world of alkaline electrochemistry as well. The ferrocyanide was a well-known positive electrode material that’s safe and stable in alkaline solution. So, we had to develop a quinone that was highly soluble and stable in alkaline solution to match up against that ferrocyanide to make the new battery that we just reported this year.

From right to left: Kaixiang Lin, Andrew Wong, Qing Chen helped develop the lab’s newest non-toxic, organic, quinone-based flow battery. (Photo: Michael Aziz)

CURWOOD: So, when it comes to scaling up, how does your organic megaflow battery, professors, stand up say against the Tesla Powerwall with its lithium-ion battery?

AZIZ: Well, the lithium-ion battery has its limitations. The powerwall looks very attractive, but it’s still constrained by the energy to power ratio. It’s of course much further advanced than our flow battery at this point; our battery’s still a little baby in my lab. And so it’s a bit hard to compare, but when we project what could happen in the scale up of our battery, we see that it could come in at a third of the cost of lithium batteries once it’s in mass production.

CURWOOD: And how does the megaflow battery compare to lithium-ion in terms of safety?

GORDON: Well, you’ve all heard of lithium batteries catching fire in an airplane, and I’m not sure I’d want a big pile of lithium batteries in my basement either.

AZIZ: This is where different storage solutions are going to be best for different purposes. If you want to drive a car, an electric car, you want a battery that’s very light and doesn’t take much space. That’s not our battery; that’s lithium. We dissolve our molecules in water, which takes up space and is heavy, but it makes it safe. Because if you’re going to store vast amounts of electrical energy in one place, you have to worry about sudden accidental release. So, dissolving our molecules in water gives our battery too much weight to drive, but it makes it safe.

CURWOOD: Professors Aziz and Gordon envision that this technology will be cheap, safe, and can be made small enough to power a single-family home, or big enough to power an entire community.

GORDON: The tanks that would be needed are on the scale of what you have in your basement as a hot water tank, but you need two of them because there are two different sides to the battery.

CURWOOD: And how cheap is it?

GORDON: Well, we think it meets the projected cost goals that the Department of Energy has put forward. That means that we’ll be able to use it effectively.

AZIZ: It’s almost as cheap as dirt.

CURWOOD: How soon, how likely is it we’ll see this on the market?

AZIZ: It’s probably three years before there are commercial systems ready for scale because you have to design, build, test, fail, figure out what went wrong, fix it, redesign, build, succeed, and then go up to the next scale. But there’s also the possibility that with our newest chemistry—it’s non-corrosive enough—it might just serve as a drop-in replacement for much more mature flow battery systems that are using electrolytes now that are just too expensive to make it big. And so, we’re investigating that possibility now. If it works out that our chemistry can get used and licensed, that only a small amount of re-engineering is required for, then this could be present in the marketplace much sooner than that.

Kaixiang Lin, a graduate student in the lab, demonstrates how their flow battery works. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: How exciting is this discovery on a scale of 1 to 10 on the stuff that you’ve done in your career?

GORDON: Well, this is right up at the top because if our future is going to be sustainable, as a civilization, we need to be able to solve these problems.

CURWOOD: Professor Aziz?

AZIZ: This is certainly the most exciting thing I’ve worked on because the implications are so global. The greatest challenge facing humanity this century—I’m convinced—is finding the energy to power a civilization of 10 billion people without unacceptable consequences to the environment. Renewable energy is front and center in that challenge, and this could really be a very significant enabler of renewable energy.

CURWOOD: Michael Aziz is a professor at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and Roy Gordon is a professor of Chemistry and Materials Science at Harvard. Thank you both.

GORDON: Thank you.

AZIZ: You’re welcome.

CURWOOD: There’s more on the flow battery at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Alkaline quinone flow battery paper

- Green storage for green energy, Harvard press release

- The Chemistry Behind The Battery That Could Outperform Tesla’s Powerwall

- Organic flow battery could transform renewable energy storage

- Quinone flow battery technologies could be competitive with current renewable energy storage

[MUSIC: AC/DC, High Voltage, Angus Young/Malcolm Young/Bon Scott, High Voltage (Epic Records)]

Beyond the Headlines

Artificial turf saves time, water and money, but concerns about its health safety are growing. (Photo: B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to check in with Peter Dykstra, and check out news lurking beyond the headlines. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and the DailyClimate.org and joins us from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. One of the most interesting reports I saw this past week was from a cable tv network where you just don’t expect to see deep, quality news on science, environment, and health risks.

CURWOOD: Would that be, what, the Home shopping Network, E, maybe the Lifetime Channel?

DYKSTRA: Well, it could be, but in this case, no. It’s ESPN, which normally brings us a mind-numbing cavalcade of sports on multiple networks. Last week, they gave us some solid journalism on a potential but unproven risk from artificial turf on thousands of school and youth sports athletic fields throughout the US. It’s a story not just about risk, but also one with some deep irony.

CURWOOD: OK, let’s start with the irony.

DYKSTRA: Well, artificial playing surfaces have been around for half a century. The original Astroturf was called Astroturf because it was first installed in the Houston Astrodome, since real grass doesn’t do well indoors. Over the years, they’ve improved artificial surfaces, and for the last couple of decades, they often used “crumb rubber”—ground-up old tires that simulate dirt. Everybody thought it was a win-win – find a better way to get rid of old tires, on fields that are more durable than real grass and don’t need to be watered and mowed all the time, right?

CURWOOD: Right. But?

DYKSTRA: But there’s concern that the artificial rubber from tires contains some hazardous chemicals. Prior studies have not revealed a risk, but several new efforts are underway. The Consumer Product Safety Commission declared crumb rubber fields to be safe in 2008, but earlier this year, they removed their blessing in favor of a neutral position on safety. Bottom line is that ESPN reported the story, to a sports-minded audience, without being either dismissive or alarmist about the possibility of risks.

CURWOOD: And I guess we’ll see if a literal “turf war” erupts. What’s next?

DYKSTRA: Well, as a society, we’re not always all that good at thinking about the future, but for the people who lose sleep thinking about future stuff, you know what one of the biggest concerns is?

The Western Hemisphere’s largest seawater desalination plant is now under construction near San Diego, California. (Photo: Jon Wiley, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, I'm guessing you're going to say climate change, but maybe you have something else in mind?

DYKSTRA: Yep. Often related to climate change, but probably just as important: Where, and how, we’re going to get our drinking water. Every option has its environmental risks – building dams and reservoirs, drawing down aquifers, and more. So as populations grow and options dwindle while epic droughts seem more common, cities turn to projects like the billion-dollar seawater desalination project near San Diego. It’s only the second major desalination plant in the U.S. – the first one, near Tampa’s been open for eight years, but to mixed reviews. In some parts of the world, desalination is more of an only resort rather than a last resort – dry Caribbean islands like Aruba and Curacao, and of course the Middle East, where the largest seawater conversion plant produces five times the volume of drinkable water that the San Diego plant will when it opens next year.

CURWOOD: Now, we’ve reported on desalination before – isn’t there some baggage associated with making drinking water from seawater?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s historically energy-intensive, but newer technologies have made the process more efficient and less costly. But when you draw in seawater in large quantities, it’s a risk for the marine environment nearby, and when you discharge the briny water that’s a byproduct of desalination, there’s potentially an even bigger risk. Nobody’s saying that seawater is the ultimate solution here – as big as the San Diego project is, it’ll only service seven percent of the region’s water needs. The plant’s success or failure will have a lot of influence over how big a player desalination is in the American water supply.

CURWOOD: Let’s move on now to the history calendar, what’s your offering this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, a month after Christopher Columbus landed in the New World in 1492, he described what we now call “tobacco” in his journal. History now records that a crew member, Rodrigo de Jerez, is the first European smoker, and wouldn’t ya know, he became quite fond of tobacco. They brought it back and started tobacco’s reign in Spain.

Christopher Columbus “discovered” tobacco in November 1492, a month after landing in the New World. (Photo: Mike Green, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So when we think of Columbus today, we think explorer, or maybe genocidal explorer, but he kicked off the tobacco business, too, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, thanks, Columbus! Tobacco is one of the few discoveries that accelerated everything from colonization and independence to slavery, Indian slaughter, emphysema and early death. Oh, and another word about Rodrigo de Jerez, pioneer smoker. As the story goes, he didn’t get to witness the tobacco craze he started in Spain. Not long after he got back to Spain, it came to the attention of the Spanish Inquisitors that this guy just got back from America was snorting smoke out of his nose and mouth, and so off to prison he went.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Well, he did have a lot to answer for! Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News - that’s EHN.org - and the DailyClimate.org. Thanks, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Sure, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more at our smoking website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- ESPN: The Turf War

- CPSC no longer stands by safety of artificial turf

- Largest Seawater Desalination Plant to Open Next Year

- Saudis Start Production at World’s Biggest Desalination Plant

- The history of tobacco

[MUSIC: Boston Pops/John Williams, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes, Jerome Kern/Otto Harbach, Unforgettable (Sony BMG)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...lots of buzz about ancient and modern bees. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michala Petri and Lars Hannibal, The Bee, Opus 9, No.1, Franz Schubert /arr.Michala Petri and Lars Hannibal, Greensleeves, Works For Recorder (Philips)]

Building a Better Honeybee

Terry Shanor, a beekeeper from Butler County, sports his favorite shirt at the annual picnic of the Pennsylvania State Beekepers Association. A co-op of beekeepers in the region are trying to breed tougher honeybees that can survive cold winters and fight back against parasitic mites. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Fall can be an exciting time of year for beekeepers. Despite the problems plaguing bees - disease, pesticides and this year a drought that’s reduced the honey flow in parts of the country, it’s still the time when bee-wranglers see the results of their and their bees work. We have a resident beekeeper right here at Living on Earth, Helen Palmer and she’s been busy as that proverbial bee.

[SPINNING OF HONEY EXTRACTOR]

PALMER: Now that’s a familiar sound to beekeepers like me, who have only one or two hives – it’s the noise of the extractor. It’s a centrifuge to get the honey out of the combs where the bees carefully store it. What we do is open up the hive and take the frames full of honey.

[BUZZING OF BEES]

PALMER: The bees aren’t too keen on that, so we puff lots of smoke at them.

[SOUNDS OF PUFFING SMOKE]

Living on Earth's Helen Palmer, a keen beekeeper, calms her bees with smoke before extracting this fall's batch of honey. (Photo: courtesy of Helen Palmer)

PALMER: Then we carefully cut the wax capping off the combs and put two or three inside the extractor and spin it, and the honey flies out.

[EXTRACTOR SPINNING]

CURWOOD: Yes, but, Helen, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. So where’s the honey for me to taste?

PALMER: Well it just so happens I do have one of my few precious jars of honey here. You can only have a smidgen though!

[SFX OPENING JAR, SPOON]

CURWOOD: Mmmm...wow that is really good. Thank you, Helen.

PALMER: You’re welcome, Steve.

CURWOOD: And you will be back in a few minutes with news of beekeeping from thousands of years ago, but meantime, we have a story from Lou Blouin of Pennsylvania Public Radio’s Allegheny Front. He has an update about one of the biggest problems facing bees in recent years – a pest that weakens hives and how researchers and backyard beekeepers are teaming up to build a better honeybee.

BLOUIN: Beekeepers have plenty of tough days. But this—this is a good day.

RAPASKI: [CHEWING] My mouth is full. We’re eating honey that is fresh from the hive. And it’s so delicious.

BLOUIN: That's Pittsburgh beekeeper Steve Rapaski. And he actually hasn’t been around to check on this particular hive in a month. And now, the bees, have built a crazy jagged, mini mountain range of foot-tall honeycomb inside an empty bee box...

RAPASKI: The good news is that it’s what we call fresh cut-comb honey. But it’s what we call a major screw-up by a beekeeper that should have put frames in there a month ago.

BLOUIN: As far as screw-ups go, it’s not really a big deal. But beekeepers aren't really allowed a whole lot of real screw-ups. And not because of colony collapse disorder. Scientists actually don’t really see much of that these days. Bee researcher Maryann Frazier says the main thing that’s been wiping out honeybees since 1990s is actually a parasite, called the varroa mite.

Typically, beekeepers insert rectangular wooden frames into bee hives so that bees will store honeycomb neatly inside the hive. As urban beekeeper Steve Repasky found out, this is what happens when you forget the frames: The bees will build a free-form comb inside the empty box, much like they would do in the wild in hollow trees. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

FRAZIER: It’s a parasitic mite that feeds on blood of adult bees and on the brood.

BLOUIN: And it’s basically like having a six-pound house cat attached to your side, sucking the life out of you. Treatments for these mites were, and still are, pretty limited. Get this: We actually spray bees—which are, of course, insects—with insecticides. The hope is we’ll kill the mites, but not the bees. The approach has worked well enough to at least give colonies a fighting chance. But out on a farm in western Pennsylvania, beekeepers are trying a new approach.

[FOOTSTEPS IN GRASS]

BERTA: Let’s go light a smoker and look at some bees.

BLOUIN: This is commercial bee breeder Jeff Berta. He’s part of a co-op of about 100 beekeepers stretching from Michigan to Tennessee that’s trying to build a better honeybee.

BERTA: Number 18, she is there. That little disc there with the 18 on it, we call those our Nascar bees because they have numbers on them.

Maryann Frazier, a researcher at Penn State's Center for Pollinator Research, checks on one of her experimental honeybee hives. Frazier is testing the effects of pesticides on honeybee colonies. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

BLOUIN: Number 18 is one of Berta’s all-star queen bees. She’s also a bit of a science experiment. This queen’s mother is from a Vermont colony that survived disease and cold winters. And then Berta had her artificially inseminated by Purdue University scientists, who developed bees with natural resistance to mites.

BERTA: The bees will take the mite and they will bite the legs and will chew on the mite. And if they bite a leg off of the mite, the mite will bleed to death. So the bees are actually fighting back. That’s the type of genetic line that we’re after right now.

BLOUIN: So now with every egg No. 18 lays, she passes on those leg-biting behaviors—making a colony that can rid itself of mites naturally, with no help from pesticides. It’s a huge breakthrough. But the breeding project can’t end there. Because Berta can’t artificially inseminate every queen, any descendants of No.18 that turn into queens themselves will likely just fly off and mate with any old drones within a few miles. Meaning, if Berta’s beekeeping neighbors don’t have strong bees too, they can easily dilute his carefully selected lines. Bee geneticist Christina Grozinger says you have to be in it for the long haul.

Bucking the paradigm in the beekeeping world, beekeeper and breeder Jeff Berta doesn't use pesticides to control mites on his honeybee colonies near Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania. Instead, he breeds bees that have natural grooming behaviors that keep colonies free of mites. (Photo: Lou Blouin)

GROZINGER: So, you can’t sort of produce a stock and say, Now I’m done! And that was it! Now we can just sell it everywhere! You have to constantly reselect and constantly have to have people very interested in working as part of this effort.

BLOUIN: That’s why Jeff Berta and the co-op of beekeepers happily give eggs from their best colonies to neighbors and swap queens to try out new genetics. It’s all part of shifting the paradigm from a system where beekeepers simply buy new bees every year, to a lasting neighborhood of bees that can slowly create real survivors. I’m Lou Blouin.

CURWOOD: Lou Blouin reports for the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- More about the honeybee and colony collapse disorder

- The varroa mite and its viruses plague honeybees

- Finding honeybee behavioral genes that help bees fight mites

- Continual selective breeding and research may help build a mite-resistant bee

The Beekeepers of Ancient Egypt

Seal amulet, 2311-2140 BCE. Bone; 2.6 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of the John Huntington Art and Polytechnic Trust 1914.684.

CURWOOD: Well, bees and humans have interacted for millennia – new research shows beeswax in use some 8000 years ago in Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, and records of beekeeping in Egypt date back to the days of the Pharaohs. A new book called The Tears of Re documents what we know and how we know it – by the way “Re” is the name modern Egyptian scholars give the sun god who most of us grew up calling “Ra.” Gene Kritsky, chair of Biology Department at Mount St Joseph University in Cincinnati wrote the book, and he spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Professor Kritsky, your book is called, The Tears of Re. Can you read the inscription that gives it that title?

KRITSKY: Certainly, the title is inspired by a papyrus that was written around 300 BCE, and it tells the story of the god Re and the origin of bees and reads:

“The god Re wept, and the tears from his eyes fell on the ground and turned into a bee. The bee made his honeycomb and busied himself with the flowers of every plant and so wax was made and also honey out of the tears of Re.”

PALMER: So, tell me what the ancient Egyptians believed about bees?

A reconstruction of the beekeeping scene in the tomb of Rekhmire based on firsthand observations by Kritsky. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Well, bees were considered sacred because they were a gift from Re. They were made from his tears and that gave bees not only a valuable aspect because of what they've contributed and brought to Egyptian society, but also they were theologically important. During the 26th dynasty, which is where the seat of the Egyptian government was at the time, in Sais the temple of Neith was called the house of the bee.

PALMER: The 26th dynasty...when about was that?

KRITSKY: That was approximately around 600 BCE.

PALMER: Now, they believed that the bees came from Re, but how important were they in Egyptian society?

.png)

The offering table with two containers of honey in the tomb of Menna. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Bees were incredibly important in the sense of...the oldest honeybee hieroglyph goes back to just shy of 3000 BCE, so it was a very ancient symbol in the Egyptian writings, but even in the old kingdom beekeeping was an important activity organized by the state. We know that honey was important because it was an important sweetener to the Egyptian cuisine; it was also used as a medicine. And we know that beeswax was used in cosmetics as well as in paintings and even in some embalming practices.

PALMER: Well, we know, of course, that honey is a very powerful antiseptic now. I presume they didn't know of that value of it, but you say it was used as a medicine. Do we know how?

KRITSKY: Yes, it was. In fact, they would use honey for cuts and for burns. But of the 900 some odd prescriptions I found in some of the various medical papyri, close to 500 of them included honey as one of the ingredients. They used honey as a way of making the medicine taste a little sweeter, but it also, as you pointed out, had antibacterial properties, which also probably included medicinal value to the concoctions.

.png)

Beekeeping relief in the tomb of Pabasa. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

PALMER: Of course, we're talking about a time when there wasn't sugar cane, there wasn't sugar beets. So there presumably wasn't any other main source of sweetener apart from honey and maybe fruit.

KRITSKY: That's correct. Indeed it was very expensive commodity in ancient Egypt and usually only the higher classes and parts of the Royal Court, for example, would have enjoyed honey.

PALMER: How do we know it was expensive?

KRITSKY: Well, we know that on a number of the papyri that talk about the rations given to workers.

We know that people who, for example, work directly with the Pharaoh would receive an allotment of honey daily, but the laborers did not.

PALMER: Is there any way of having an objective sort of like money value of it? Do we have any clue about that?

Part of a beekeeping relief at Pabasa’s tomb. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Well, one of the things that's really, I think really interesting about ancient Egypt is that their economy was not currency-based like ours. Their entire economy is based on almost like a bartering economy. It was based on the concept of the deben, and that's a quantity of copper which could be used to make a certain-sized vessel. And they didn't carry around pieces of this copper. Instead if you're to be paid, let's say two bags of grain for a day’s work and the person paying you didn't have the grain, he or she could pay with an equivalent value of another commodity. It could be honey, it could be beer, it could be something like that. But they had a very complex understanding of the comparative value of various things that were needed for daily life.

PALMER: In your book you have some wonderful pictures of cave paintings and papyri that show honey. It was also used as a kind of tribute from the various provinces to the Pharaoh?

KRITSKY: Definitely. In the tomb of Rekmire, you'll find a whole series of paintings that show tribute being paid in the form of honey.

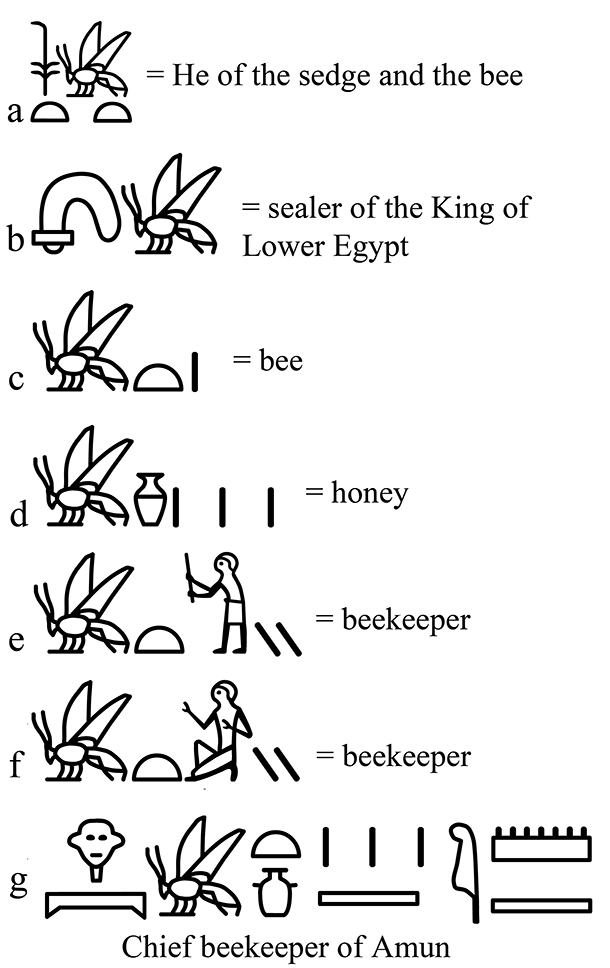

PALMER: So how much can we read about what the hieroglyphs tell us about bees?

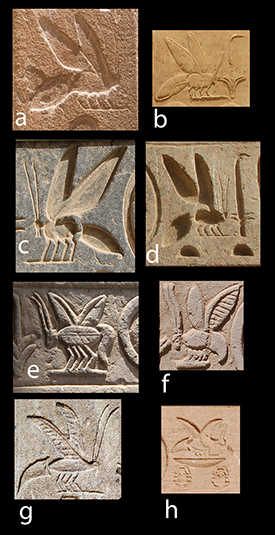

A honeybee hieroglyph throughout Egyptian history. a. Tomb of Mereruka, Sixth Dynasty; b. Deir el-Bahri, Eighteenth Dynasty; c. Ramesseum, Nineteenth Dynasty; d. Medinet Habu, Nineteenth Dynasty; e. Kom Ombo, Ptolemaic Period; f. Kom Ombo, Ptolemaic Period; g. Philae, Ptolemaic Period; h. Kalabsha Temple, Roman Era. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Well, the Egyptian hieroglyph language was quite complex compared to ours. In addition having consonants like we have with our alphabet for example, they had over 700 hieroglyphic symbols, and the honeybee hieroglyph could represent with a certain notation to mean a bee, the actual insect, but it also formed the syllable bit. So if was part of the royal titular, which was Nesu-Biti, that would mean the King of Upper and Lower Egypt that represented the delta or Lower Egypt region of the country. It's also used in the word for honey, and it's also used in the word for beekeeper and symbolized, in the case of the word for beekeeper, you have a laborer next to a honeybee with the consonant for the t, that basely symbolized the occupation for the beekeeper.

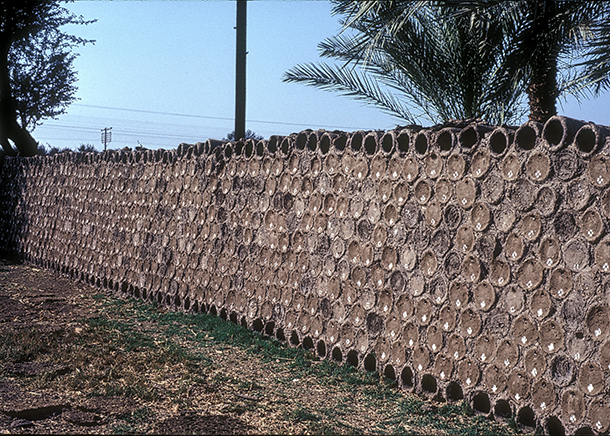

PALMER: Describe for me what the ancient Egyptian hives were like because they are quite different from the kind of hives we have today.

KRITSKY: Oh, they certainly were quite amazing. They were these horizontal tube hives. They were made out of mud that was dried into large cylinder and then stacked on top of each other, very similar in the construction of the hives we still see used in Azerbaijan and Iran, for example.

PALMER: Do we have any real understanding of exactly how they practiced beekeeping? Can you say to me if I were an Egyptian beekeeper what would I be doing on a daily basis or on a monthly basis?

KRITSKY: Well, we don't have any real evidence of how they actually kept their bees, but there are some practices that we can discern from the temple and tomb paintings. We know, of course, they used horizontal hives, but in one of the hives, the oldest one from 2450 BCE, we actually see the beekeeper holding something to his face and it's right up against the opening of the hive. The hieroglyph above it means “to weaken” or “to slacken” or “to emit a sound”, and that's been interpreted as smoking bees - which is a way of quieting bees - or may be calling bees. One of things the traditional Egyptian beekeepers practiced, they would call the queen, make a little sound and the queen would respond. That would tell them if there was a queen ready to emerge or what was the status inside the hive. If that was the case then their beekeeping was much more sophisticated than we can appreciate.

Egyptian words and phrases that incorporate the honey bee hieroglyph. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

Once they got the honey, we have a painting that shows them removing round honeycomb from these horizontal hives. The honeycomb was crushed and then placed into containers. There's a sub-discipline called experimental archaeology. So of course I had to do this...I took honeycomb and I crushed it, and I put it in a container in hot sun and the beeswax floated the top and the honey stayed below the beeswax. And in one of the reliefs we actually see one of the beekeepers holding a vessel - it has a spout coming from not the top of the vessel but from the middle or towards the bottom - much like a gravy separator or a fat separator used for making gravy, and that may be one way they could've decanted a lot of the honey and not getting a lot of the wax mixed in with it. Once they had the honey separated from the wax, they would seal it in jars. In the Old Kingdom these jars were large and round. In the New Kingdom we see these sort of almost diamond shaped vessels that were like two bowls with the bottom bowl filled with honey and then a ring of wax along the middle and then another bowl on top and that was the typical container that was used to hold the honey.

PALMER: Now, you say they not only used the honey, they also made use of the wax. Tell me a bit more about how they used the wax.

KRITSKY: We know that wax was used in cosmetics, for example, they wore wigs and they would keep the curls of the wigs in place by using beeswax. We have evidence of beeswax being found in a very thin layer on some mummies, so it was used as a preservative that way but it wasn't going to be prevalent enough for the broader context. But beeswax was also important as a wonderful magical substance. Beeswax when it burns, it burns with a very bright light. It also doesn't leave any ash. Moreover, if you put beeswax in the hot Egyptian sun, it will start to change, it'll get a little molten like, a little liquidy. And so all these tied in with their solar theology would've been important to the Egyptians, and so they had a number of ways that you could take beeswax carvings, for example, if you wanted to ward off evil by taking a hippopotamus for example and carving it into an beeswax and igniting it and burning it away, that would be one kind of magic that would help form a protective spell, for example.

.png)

Four beeswax sons of Horus. From the left: Hapy, Duamutef, Imsety, and Imsety. Third Intermediate Period, late Twenty-first Dynasty (1069-945 BCE) or early Twenty-second Dynasty (945-715 BCE) (Photo: used with permission of the Cleveland Museum of Art)

PALMER: Wow, so you are, I know, a beekeeper yourself. Do you feel kinship with these ancient Egyptians and their beekeeping?

KRITSKY: Oh, I really do. There's something...if anybody out there has not kept bees or if they have kept bees they'll know what this like. Of course, western beekeeping, we're wearing the veil, the protective gear, and it sort of limits your peripheral vision. You've got your smoker going, and when you open up that hive and you smell the sweet smell of the honey and the honeycomb, and if when you're really at one with your bees you don't use gloves anymore. It's almost like a tai chi. You're carefully moving the frames around, so the bees don't get alarmed and don't sting you and so on. To me it's a very ancient occupation because it goes back to ancient Egypt obviously, but there's something that's kinship with us, humans and bees, that I find very alluring.

PALMER: Now so as far as we know, they didn't have some of the problems that beekeepers have today, and I know that you are actually working on bees and some of the problems in your current research. Can you tell me a little about that?

A wall apiary south of Minya in central Egypt. (Photo: Gene Kritsky and used with permission.)

KRITSKY: Certainly. I'm working in association with Dr. Andrew Rasmussen, he's our microbiologist here at Mount St. Joseph University, looking at the impact of fungicide contaminated beeswax foundation which is used to actually give the bees a little bit of a head start when they are starting a hive. So we're going out and we're seeing what flowers are the bees visiting. We're sampling those flowers for natural yeasts and fungi and we're intercepting the bees with their pollen balls as they're entering the beehive to get the pollen balls and then we're going into the hive itself to sample what the pollen is doing in the hive. The bee basically inoculates that pollen with yeasts which ferments the pollen into what we call bee bread - which is called bee bread because it actually smells like bread dough - and that fermentation that these yeasts do in the pollen helps convert it into the bee bread which the bees use as a food product.

Entomologist Gene Kritsky at Edfu (Photo: ©Jessee Smith, courtesy of Gene Kritsky)

PALMER: Typically when people are making new frames they put in a wax foundation, which is shaped like a honeycomb that tells bees where to actually build up walls. Are you saying that this foundation that all of us beekeepers buy and put into the hive is already contaminated with fungicide?

KRITSKY: Yes the recent papers have shown that close to if not all the foundation that's being manufactured now has fungicides already present in that wax and this may be a contributing factor to some of the bee health problems because the bees aren't getting the same nutrition they normally get if indeed natural yeasts are not present. And that's what we're trying to find out with our research. We're trying to see do these that yeast we're finding in the flowers, that we find in the pollen balls, how long are they still surviving in the honeycomb as the pollen is converted to bee bread.

PALMER: Wow, that's really interesting. I didn't know about the fungicides on the foundation.

KRITSKY: And it's not just fungicides. There's insecticides on some of the wax as well, so there are a number of laboratories around the states and in Europe that are looking at this question because it's rather critical because bees are important for life.

CURWOOD: That’s Gene Kritsky, Entomologist, Chair of the Biology Department at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati and author of The Tears of Re. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer. And by the way, we asked what his current research on pesticides and fungicides in wax had discovered, and he told us “it’s still too soon.”

Related links:

- The Tears of Re from Oxford University Press

- Video: Kritsky on Advanced ancient Egyptian beekeeping techniques

- Video: Kritsky on Medicinal uses of ancient Egyptian beekeeping

- Video: Kritsky on the economic value of beekeeping

- About entomologist Gene Kritsky

- Prehistoric farmers were first beekeepers

[MUSIC: Norbert Kael, The Flight Of the Bumblebee, Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov/arr. Norbert Kael, (Available on Norbert Kael's website, http:// www.norbertkael.com/music- video.html. Not commercially available.)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you from the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, and Jennifer Marquis. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, and Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more; www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth