July 26, 2013

Air Date: July 26, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Microbes and Evolution

View the page for this story

The bacterial fauna on our bodies and in our guts can do more than regulate digestion. A new study in the journal Science says microbes can influence evolution. Host Steve Curwood talks to Seth Bordenstein, co-author of the research that some evolutionary biologists are calling groundbreaking. (07:40)

Challenges for the New EPA Chief

View the page for this story

The race is on for the recently confirmed head of the EPA, Gina McCarthy, to get rules in place that restrict global warming emissions from power plants, before President Obama leaves office. For an inside look at Ms. McCarthy's road ahead, host Steve Curwood talks with Carol Browner, EPA chief in the Clinton administration, and climate czar during President Obama's first term. (06:05)

Science Note: Palm Oil

/ Poncie RutschView the page for this story

A group of geneticists have found a gene responsible for palm oil yield, which could help make palm oil farming much more efficient in the tropics. Poncie Rutsch reports. (01:30)

Radioactive Water from Fukushima in the Pacific

View the page for this story

More than two years after the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan had a meltdown following flooding from a tsunami, radioactive water is likely seeping into the Pacific Ocean. Argun Makhijani, President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, tells host Steve Curwood that Japanese officials still don’t know how to contain the radiation fully. (05:50)

Trash in Kerala

/ Meara SharmaView the page for this story

India is developing fast and rising salaries bring more consumption, and much more trash. In south India, a village chosen as the site of a trash disposal facility has rebelled. As Meara Sharma reports, it refuses to accept any more garbage from a nearby city. (10:15)

Zero Waste Atlanta

View the page for this story

From organic food to composting to replacing plastic straws with paper ones; eco-activist Laura Turner Seydel tells host Steve Curwood there are a lot of easy things the restaurant industry can do to become more sustainable. (04:10)

Citizens on the Watch for Hummingbirds

View the page for this story

Hummingbirds are particularly susceptible to the changing climate because of their speedy metabolism and lengthy migrations. They need a reliable nectar source, but some flowers now blossom earlier. National Audubon Society scientist Geoff LeBaron joins tells Steve Curwood about a new citizen science project to monitor hummingbirds in the US. (05:25)

National Moth Week

/ Ari Daniel ShapiroView the page for this story

From July 20th to 28th, citizen scientists in the US and forty other countries celebrated National Moth Week, by taking moth walks and heading out with flashlights to find the elusive night-fliers. Ari Daniel Shapiro reports. (05:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Seth Bordenstein, Carol Browner, Arjun Makhijani, Laura Turner Seydel, Geoff LeBaron

Reporters: Poncie Rutsch, Meara Sharma, Ari Daniel Shapiro

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. There is a major breakthrough in understanding how creatures evolve. It relates to the millions of microbes that coexist with other species, including us.

BORDENSTEIN: We’re all walking bags of microorganisms, and we should be proud of that because without the microorganisms, we would simply die and they would live on, and so they are essential to our fitness and our health.

CURWOOD: And science has found microbes are apparently key for evolution.

Also, the tricky and delicate path the new EPA administrator has to navigate to cut more greenhouse gas emissions.

And heading out into the darkness, in search of stealthy night fliers.

MOSKOWITZ: There’s something kinda magical about being out at night with all kinds of biodiversity - everything from the size of a pinhead up to a moth the size of your hand.

CURWOOD: It’s National Moth Week. That and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic smoothies, yogurt and more.

Microbes and Evolution

An artistic rendering of the Nasonia wasp.

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. There is a major breakthrough in research into evolution and genetics. It seems that our own genes tell only part of the story of how our bodies work. Now research funded by the National Science Foundation shows that the microbiome is also key to speciation, the process by which new species evolve. Seth Bordenstein is an Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at Vanderbilt University, and co-author of this new study. Welcome to the show.

BORDENSTEIN: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Now this is pretty complicated science. Can you just walk us through briefly what you did in this experiment?

BORDENSTEIN: Sure. Every animal has a gut, and within that gut is a large population of bacterial cells that scientists called the microbiome. And we appreciate how important it is today in health and disease. We know far less about whether the microbiome is essentially important to the evolution of animals, and plants for that matter. And what we set out to do was test the hypothesis that new species of animals can arise through changes in their gut bacteria or gut microbiome.

CURWOOD: How do you do that?

The hologenome theory suggests that not just individual organisms, but their collective microbial communities as well, are the object of evolution. (Bigstockphoto.com)

BORDENSTEIN: Well you do that with an excellent system to examine speciation, and so we have selected a parasitic wasp. And this wasp has four very closely related species in it. Essentially they're undergoing speciation right now, and it allows biologists to capture the key events that contribute to the origin of new species. And we realized that when these species interbreed and they can make what's called a hybrid, that the hybrids sometimes die. They don't survive to adulthood. And for a while people had asked why is it that these hybrids are dying. People ask this question in many systems: why do hybrids die between closely related species.

CURWOOD: And I'm guessing that what you found is changes or differences in their gut bacteria make the difference.

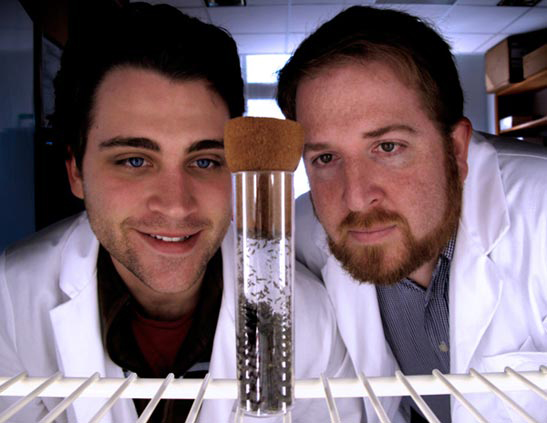

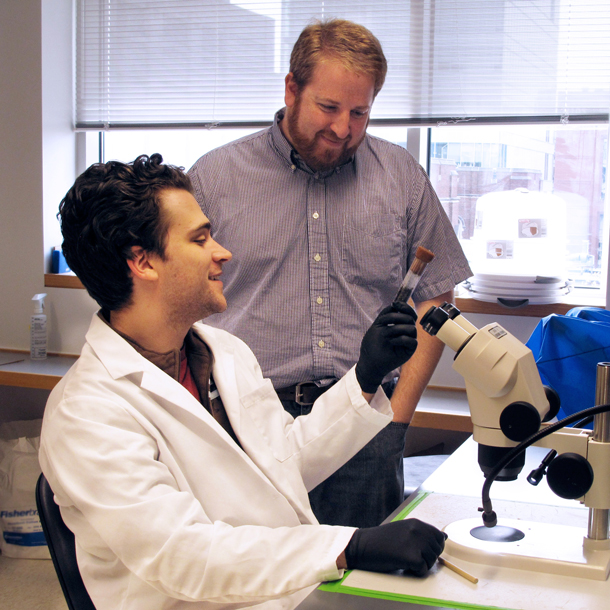

Co-authors Robert Brucker (left) and Seth Bordenstein (right) of Vanderbilt University (Seth Bordenstein)

BORDENSTEIN: That’s correct. And it's not just changes in the gut bacteria, but changes in the genes, and that it really takes two to tango. It takes both the gut bacteria and the genes inside the animal cells to drive the origin of these new species.

CURWOOD: Now how did you find the effects of evolution along with microbiome by looking at the hybrids of these wasps?

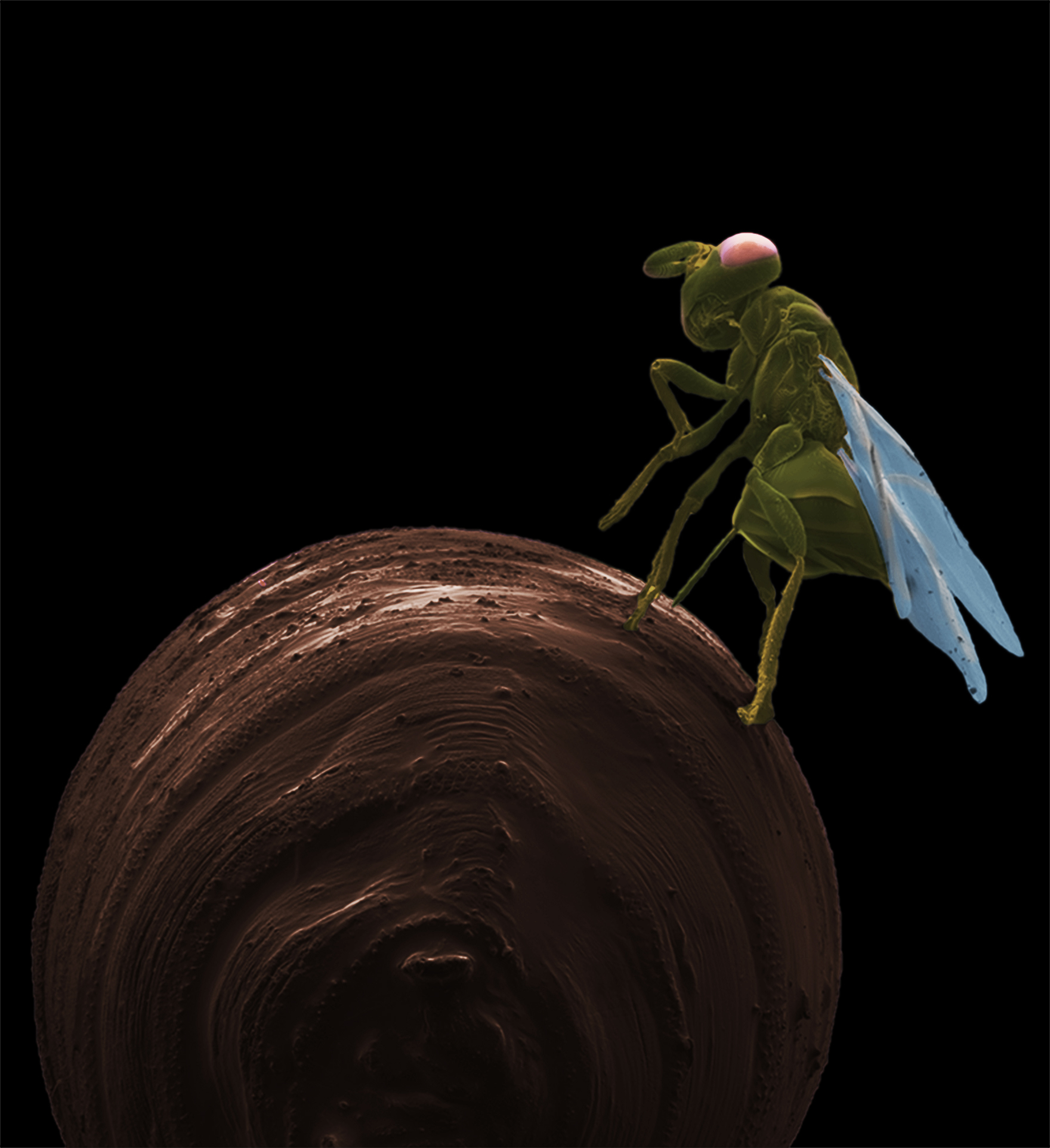

Nasonia vitripennis, one of the parasitic jewel wasps used in this study (M.E. Clark)

BORDENSTEIN: So these wasp hybrids showed a very interesting trait in which their gut microbiome looked different than the parental species, the non-hybrids. And we decided to eliminate the microbiome from the hybrids and see what effect that would have on their death. And remarkably, we found that the hybrids lived when we took the microbiome away, indicating that the bacteria are essential to causing hybrid fatality.

CURWOOD: And meaning then that bacteria are essential in this process of evolution?

BORDENSTEIN: Correct. Because speciation is the process by which two organisms can't interbreed anymore, and we showed that the microbiome is essential to that process.

CURWOOD: Now your research touches on a controversial idea in evolutionary biology called the hologenome. What is that?

One of the first proponents of the hologenome theory of evolution worked with fruit flies (Bigstockphoto.com)

BORDENSTEIN: So the hologenome is basically the aggregate genome of an organism. That is, if we consider the microbiome and the cell’s mitochondria and the cell’s DNA together, and we sum this information...this genetic information up. Some folks consider this a hologenome, the total genetic information of an animal or a plant, and that the object of evolution is not just one of these genomes, but all of them together. And that's what changes through the origin of new species.

CURWOOD: Well wait a second here. Us humans, we have 10 times as many microbial cells as our own selves. So we're only 10 percent of the genetic game for being human?

BORDENSTEIN: I'm sorry, but we are. We're all walking bags of microorganisms, and we should be proud of that because without the microorganisms we would simply die and they would live on. And so they're essential to our fitness and our health.

CURWOOD: So what other studies have there been to support this hologenome theory?

Micrograph of one of the Nasonia wasps (Robert M. Brucker)

BORDENSTEIN: So the hologenome theory is in its early days, and it’s arguably something that will have a lot of questions around it. Conceptually, the two founders of the hologenome theory, Richard Jefferson and Eugene Rosenberg, have come up with the description of the theory. And Eugene Rosenberg's lab from Israel has found that if you take a single species of fly, the same species, and you split that species and cultivate it on two different diets, and then you bring these flies back in contact with each other and ask, “do they mate?” , they stunningly found that these flies didn't mate when they were reared on different diets, but yet they were considered the same species. They were able to find that it was the bacteria in their guts that changed that helped contribute to this mating discrimination that they saw in this one species.

CURWOOD: I mean, at the end of the day, does that mean somebody who eats big Macs wouldn't get along with somebody who is a vegan?

BORDENSTEIN: Well, probably not, but we do know that microbes affect the way we smell, and if individuals choose to date or find the partners based on their smell, then that is a form of discrimination that is occurring. And if it happens at the population or species level then new species will be arising, and so while anything is possible in biology, I doubt that humans will be splitting into different species.

CURWOOD: Now sometimes in the process of heredity genes become more or less active, or sometimes can work in different ways. What role do you think microbes might play in turning genes off and on?

BORDENSTEIN: That's a great question. So microbes will clearly turn on immune genes when they are present. The immune genes serve as essentially the guardians of the host defense system. But there may be many biological processes as we learn about the microbiome that could be turned on, for example brain development, digestion, the way we smell. These are things that increasingly the microbiome is shown to have a role in.

Researchers Robert Brucker (left) and Seth Bordenstein (right) in the Bordenstein Lab (Seth Bordenstein)

CURWOOD: Wait a second. You’re saying that bacteria govern how well we might develop our brains?

BORDENSTEIN: Indeed. So there is an excellent experiment done where they observed brain development in germ-free mice. Germ-free are simply mice that don't have microbes in them. And they showed some severe deformities in their brain structure indicating that perhaps the brain and the nervous system is dependent upon a proper gut microbiome to be present in that mouse, and perhaps this is common phenomena in other animals.

CURWOOD: So what's been the response of the scientific community so far to your findings?

BORDENSTEIN: The response has been quite nice. We seen quotes of calling this work ‘groundbreaking’, and it is early days for this work. So we've also seen some people say we really don't know how common this phenomenon will be yet, but I think that the most exciting research happens at the frontier, the edge of science where we know the least. And if we don't take the risks to confront these exciting ideas, we’ll never know if they're correct or not.

CURWOOD: What's next for hologenome research?

BORDENSTEIN: The next phase is hopefully this paper excites people to go into their own systems to examine how common speciation by microbes are, how common the hologenome theory is. So it's not just us, but it's going to be hopefully many labs that start to confront this question were we could have a unified framework under a hologenome theory or not, depending on what the evidence is.

CURWOOD: Seth Bordenstein is an Associate Professor of Biological Sciences at Vanderbilt University. Thank you so much. This is truly fascinating research.

BORDENSTEIN: Thank you, again.

Related links:

- Learn more at the Bordenstein Lab

- A blog about symbiosis and one of Life's great rules - Out of Many, One - by Prof. Seth Bordenstein

- Live in symbiosis, Robert Brucker's blog

- Seth Bordenstein's Twitter

- Robert Brucker's Twitter

- Vanderbilt’s write-up of the research

- the study

[MUSIC: Bordenstein: Funkadelic “A Joyful Process” from America Eats It’s Young (Westbound Records 1972) Happy Birthday to the Funkmeister George Clinton 07/22/1941]

Challenges for the New EPA Chief

Coal power plant stacks ( Big Stock Photos)

CURWOOD: When President Obama presented his climate protection plan in June, he also ordered the EPA to get moving on rules to restrict carbon emissions from electric utilities. The administration had already instituted limits on emissions from cars and trucks, but power plants are even bigger polluters. Trouble was, the confirmation of a new head of the EPA had been long stalled on Capitol Hill. But on July 18, Gina McCarthy was finally confirmed, and she now faces a grueling schedule for this rule making, and fierce opposition from some in Congress and industry. For an inside look at her road ahead we turn to Carol Browner, EPA chief in the Clinton administration, and climate czar during President Obama's first term. Welcome to Living on Earth.

BROWNER: Thank you. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: It took a long time, but Gina McCarthy has finally been confirmed.

Gina McCarthy (photo: United States Government)

BROWNER: No, it's great. I mean it did take much too long, but the good news is she's there, she's gonna be great, she's got the right experience and there’s a lot to be done.

CURWOOD: So you’ve been in her shoes, Carol Browner. What's it like to run an agency like the EPA?

BROWNER: Well, first of all, it’s an honor. You get to come to work every day and think about how to make our air a little safer, our water a little cleaner. I think she faces a particularly complicated challenge. The President has called on EPA to move forward with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and that's going to be complicated, but obviously very, very important. And I think she can do it.

CURWOOD: How supportive do you think the President is going to be in her efforts here?

BROWNER: Well, I think he’s very supportive. He's done something that never happened to me in my eight years at EPA, which is he's signed an instruction to EPA saying ‘get this done’. You know, whenever EPA does something, inevitably they go into the White House, to go to OMB [Office of Management and Budget], and there’s a lot of back-and-forth debate about whether or not EPA should be doing it, and once you cross that bridge, then how it should be done. Well in the case of this, the President has taken off the table that first debate - whether or not this should happen. He said, it should happen. There will still be debate about the best way to make it happen, but that's a real, real indication of where the President stands - his willingness to say ‘we’re not going to debate yay or nay, but we're gonna do it, let's move forward’.

CURWOOD: Well, the President issued a memo saying this, and it's rather ambitious in its timetable. It tells the EPA to have a new proposal together before the end of September this year in terms of dealing with power plants.

Carol Browner speaking at a press conference with President Obama and Vice-President Biden (photo: Obama-Biden Transition Team)

BROWNER: Well, I think what you see in the Presidential memorandum to the EPA, to Gina, is recognition from the President that they need to get the entire process done before the President leaves office. And so, if you work the calendar backwards, they need to get going because after they propose the standards, then they have to finalize the standards, then the states have to write plans about how to meet those standards. There’s a number of steps in the process - all hugely important. I have every confidence that EPA and Gina will pay attention to those steps. That’s what the President was thinking about. He knows, believes, that climate change is real; he believes we have an obligation to do something; he wants to do something; he has done something, and this is the next step in the process.

CURWOOD: Explain for me what the relationship is between the EPA and the states for this rulemaking?

BROWNER: So the section of the Clean Air Act, the law that EPA will be using to do this work, gives the states a very, very important role. Once EPA determines how much of this pollution we need to take out of the air, then the states actually write the blueprint. They write the plans for where those reductions are going to come from. And so it's important to engage the states, not just at that point in the process, but from the very beginning. They will have good ideas about how best to find the most cost-effective reduction of these greenhouse gas pollutants.

CURWOOD: So a state could, what, have a cap-and-trade program like California, or just set a particular standard?

BROWNER: That's an interesting question, and I think there are lots of folks who do think a state could use some sort of trading mechanisms, some sort of a regime that allows you to look across all of the sources of electricity generation that put out this kind of pollution and then allow the industry to work across those facilities. You might have a situation were several states would sign up to the same cap-and-trade program, and then they would work across state lines like the RGGI program, like that which is the northeast program, or like the California program.

CURWOOD: Now the House Appropriations Committee just announced their plans to cut EPA’s budget by some 34 percent, and eliminate any new greenhouse gas regulations. It seems that Gina McCarthy...well, it’s not going to be easy for her, is it?

BROWNER: [LAUGHS] Well, the good news is we have two bodies. The Senate would have to agree. I mean, look, the American people don't want the environmental cop off the beat, you know, there’s a lot of other work that EPA does in addition to this focus on greenhouse gas pollution, and I don't think these cuts are likely to stand up. And it’s also disappointing that apparently the House of Representatives doesn't believe in good science because part of what they're cutting is not just enforcement, it’s also the science work of the agency. But I think at the end of the day, the Senate will not agree to those cuts.

CURWOOD: So we have limitations on CO2 emissions from cars and trucks. There's been progress on the household emissions energy standard, but the power utility sector has been real tough to get agreement on - all these court cases over the years. How much is riding on these rules?

BROWNER: Well this is a big chunk of emissions. What comes out of the power sector in terms of these pollutants is significant, and you know the administration has already done, as you said, transportation, they’ve looked at appliances that we use in our homes, and so this is the next big chunk. I think for the President to fulfill his commitment, partly the commitment he made in Copenhagen, for example, this is the next single thing that has to happen.

CURWOOD: Carol Browner is the former climate czar for President Obama and former head of the EPA for President Clinton, now distinguished Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Thanks so much for taking this time with me today.

BROWNER: Thank you, Steve.

Related links:

- President Obama’s memorandum ordering the EPA to act on power plant emissions.

- Full text of President Obama’s climate action plan

- Video of President Obama’s June 25, 2013 climate change speech

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Visit Carol Browner’s webpage at the Center for American Progress

CURWOOD: Coming up...getting dumped on...literally...and how one village in the south of India is fighting back. That's next on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Bonobo “Cirrus” from The North Borders (Ninja Tune 2013)]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Billy Taylor : “Two Shades Of Blues” from Homage (GRP records 1995)

Happy Birthday to the late Dr. Taylor 07/24/1921 -12/28/2010)]

Science Note: Palm Oil

The fruit of the oil palm looks like a coconut, with fruit on the outside of the shell and palm oil on the inside of the shell (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. In a minute, more trouble at the Fukushima nuclear power complex in Japan. But first this note on emerging science from Poncie Rutsch.

RUTSCH: Over half of the vegetable oil used worldwide in cooking, cosmetics, and cleaning comes from a tropical oil palm tree, that’s often planted on deforested land. The most popular oil palm species comes in three types, which yield different amounts of oil.

The oil palm kernels can grow a thick shell, and produce a small amount of palm oil. They can grow with no shells, and produce no fruit or oil. Or they can grow thin shells, and produce a lot of palm oil. But there was no way to tell which type a tree was until it grew large enough to bear fruit.

As early as the 1920s, breeders guessed that a single gene controlled both shell growth and oil yield. They called it the Shell gene. Now, a group of geneticists have found the Shell gene.

A woman works in an oil palm nursery in the tropics (Photo: Big Stock Photo).

Rob Martienssen at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, worked with the Malaysian Palm Oil Board to complete the oil palm’s genome. They determined that by mapping the genome of the oil palm seed before planting, they could select only the trees with thin-shelled fruit – the ones that will yield the most palm oil.

The new discovery should enable palm oil farmers to produce the same amount of oil using fewer trees and less land.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Poncie Rutsch.

Related link:

oil palm tree

Radioactive Water from Fukushima in the Pacific

Fukushima Reactors 3 & 4 after meltdown of 3 began. ( Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: Back in March of 2011, a huge earthquake off the coast of Japan caused a tsunami that crashed over the Fukushima nuclear power complex. One of the four reactors suffered a meltdown, and today radioactive material is still being released into the environment. Now there are new concerns that radioactive water is leaking into groundwater and ultimately flowing into the Pacific Ocean near the facility. Arjun Makhijani is President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. We called him up to find out what type of radioactive material could be getting into the ocean.

MAKHIJANI: Well, they have got three different radionucleotides in large quantities and concentrations in the groundwater under the plant, which is strontium-90, which mimics with calcium, goes to the bone; cesium, which mimics potassium, goes all over the body; and tritium which is like water, so also goes all over the body. So these are quite mobile, strontium and tritium particularly, and so these are the ones that would wind up in the ocean and also in ocean life. But currently it’s unclear how much of the contamination is reaching the ocean.

CURWOOD: So how much might that radioactive water affect human health once it gets out into the environment?

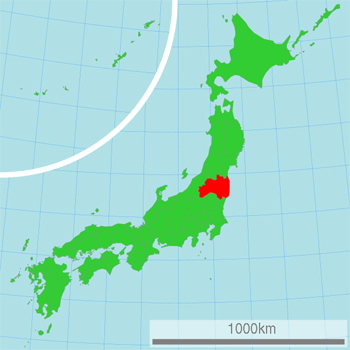

Fukushima Prefecture is featured in red. (Wikimedia Commons)

MAKHIJANI: Well, the strontium-90 and the cesium would both be perilous, and since the strontium-90 is more mobile and also more dangerous biologically, strontium behaves like calcium, so it goes to the bone. It also bioaccumulates in the base of the food chain and algae. Ultimately because it does bioaccumulate and there is quite a lot of strontium, you could have a large part of the food chain near Fukushima being contaminated.

CURWOOD: Now, what happens to people who are exposed to strontium-90?

MAKHIJANI: The effects, of course, affect your chances of getting cancer all over the body, but specially in the organs that it targets. It’s like the bone and bone marrow. It’s a special problem I think for pregnant women because the stem cells of our immune system are formed in the bone marrow. So when the stem cells are being formed, if pregnant women drink contaminated water, or eat contaminated fish, the outcomes could be worse than cancer because then you’re talking about a much more compromised child in the sense of having a compromised immune system - it makes you more vulnerable to all kinds of diseases.

A large area around the Fukushima nuclear facility will be uninhabitable for generations.

CURWOOD: Now, it’s been two years since this accident, but this nuclear meltdown reactor is going to be hot for quite a long time. Just how long will it be super hot?

MAKHIJANI: Well, the cesium and the strontium have half lives of about 30 years, so we’re talking several hundred years there. But there are, of course, other materials, like plutonium, which has a half life of 24,000 years and so on. There are fission products that have half lives in the millions of years so you’re talking about radioactivity that’s essentially forever. And you know Chernobyl, where there was an accident in 1986, has become a permanent waste dump. It’s very, very unclear to me how they are going to be able to get at this molten fuel, extract it from the bottoms of these highly damaged buildings and package it for safer or less dangerous storage or disposal. Right now, they’re still, two years later, trying to contain the situation on an emergency basis.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, of the 50 or so nuclear reactors that Japan had before the Fukushima disaster, 48 or so of them have been shut down. So how is Japan getting electricity in the meantime? And what are, do you think, the government’s plans to start up nuclear plants again in Japan?

TEPCO has admitted that radioactive water from the Fukushima nuclear facility is likely leaking out of the plant and making its way to the ocean.

MAKHIJANI: Well, they had 54. Of course, four were damaged by the accident. And so that leaves 50, and two are operating as you said. There’s a lot of public resistance to opening the others. So they’re getting their energy from a number of sources. First of all, they’ve got a highly coordinated conservation program. They’re importing more fossil fuels. And they are trying to rapidly increase their renewable energy production - both wind and especially solar. But the government policy of the present prime minister is to restart the reactors.

CURWOOD: So, now more than two years since the Fukushima accident, and the problem seems to be far from contained, how can the Japanese get a handle on this going forward from here?

MAKHIJANI: It’s very, very unclear in terms of what is going to happen with Fukushima. Of course, it is in a seismic zone, so one of the big dangers is this highly radioactive waste sitting in these pools. If that infrastructure that is now damaged becomes much more damaged, then the devastation could be quite great, and much more of it could wind up in the oceans. I mean, they have millions and millions of gallons of radioactive water that is stored in tanks on site, near the site, and they’ve been building tanks like they’re going out of style and they just cannot keep up. And they have no idea what they’re going to do with these millions and millions of gallons of contaminated water, and that’s just one of the problems. The other one is, they’ve got this molten fuel at the bottom of these reactors. It’s going to be extremely difficult to get at it. So, the general idea is that it’s going to take them decades - this is an accident that’s shockingly not stopping - even the emergency is not over.

CURWOOD: Arjun Makhijani is President of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research in Maryland. Thank you so much, Arjun.

MAKHIJANI: Thank you, Steve.

Related link:

Institute for Energy and Environmental Research

[MUSIC: Funkadelic “Good Thoughts, bad Thoughts” from Standing On The Verge Of Getting It On (Westbound Records 1974)]

Trash in Kerala

Uncollected trash piles up all over the city of Trivandrum. (Meara Sharma)

CURWOOD: India was once on track to achieve enormous economic growth, and with a population of more than a billion, the world’s largest democracy was expected to become the world’s third largest economy by the middle of the century. But the promised economic growth has slowed markedly, and surveys show India is now one of the worst places to start or run a business, and infrastructure is woefully inadequate for its growing population. Among the symptoms of India’s failure to manage its leap into the 21st century are the villages near major cities that have become dumping grounds for urban waste - often with little planning and disastrous effects. But in the southern state of Kerala, one trash-burdened village is fighting back, as Meara Sharma reports.

SHARMA: There’s a funny smell in the air in Vilappilsala. It has the same whiff of sulfur you get in rotten eggs, mixed with decaying fruit, spoiled meat, and a hint of something chemical. It’s like that school painting class when you mixed all the colors together, and no matter how much red or yellow you added, it always turned out sludgy brown. This foul stench is the result of all the pungent rubbish a big city produces, thrown into one big pile in the village of Vilappilsala. And the villagers don’t mince words about their home.

VILLAGER 1: It is the most dirty place in the Kerala state. They are a dumping yard.

Members of the Vilappilsala panchayat (village council). To protest the garbage they've kept an ongoing hunger strike for over two years. (Meara Sharma)

SHARMA: 13 years ago, the corporation of Trivandrum - the capital of Kerala - chose the nearby village of Vilappilsala as the site of a new disposal facility to process the waste of the growing city. They commissioned a private company to build and operate it. The company planned a state of the art plant that would transform some of the wet waste into compost, or bio manure, that could be sold for profit.

A woman beside her house in Vilappilsala. She lives across the street from the garbage facility. Most of her neighbors have fled their homes. (Meara Sharma)

As construction began, the residents of Vilappilsala were unaware of what exactly was planned. But Trivandrum-based sociologist Devika Jayakumari says they welcomed the prospect of development.

JAYAKUMARI: People in Vilippilsala, let me tell you, were also eager about growth, and things like that.

SHARMA: RVG Menon is an engineering professor and local environmentalist from Trivandrum. He’s kept an eye on Vilippilsala and the private company’s trash facility for years.

MENON: The private party had made calculations that if they convert 300 tons into bio manure, they could get enough revenue from it.

SHARMA: However, things didn’t exactly go according to plan.

MENON: Then they realized the manure that was produced by the plant did not have that much demand in the market, and then the private parties decided to process only that much quantity of waste which will produce sellable amount of manure.

A villager showcases leachate-polluted water from the river in Vilappilsala. (Meara Sharma)

SHARMA: But though officials at the garbage facility planned to limit the amount of waste they processed, trash from the city still came in by the truckload, day after day. The company processed a fraction of the waste, and just dumped the rest - much to the dismay of the villagers.

VILLAGER 2: Gradually after 12 years it was like a huge mountain.

SHARMA: A noxious mountain that oozed black sludge and poisoned the river. After a few years, the green, coconut palm-fringed village of Vilappilsala – and its inhabitants – began to feel the physical toll of the waste.

VILLAGER 3: In 2005, the dumping yard created so many problems - air pollution, water pollution, and everything. They have so many diseases, skin diseases, some asthmatic problems, breathing problems. Because the waste smell is creating asthma.

SHARMA: Trivandrum-based sociologist Devika Jayakumari remembers how the once pristine village turned foul.

JAYAKUMARI: The dirt was just pushed into a local stream. I remember seeing that stream before the plant – it was a beautiful silver rivulet. Turned into, dark thick, black thick, ugly, horrible smelling waste stream is what you see now.

SHARMA: Kerala is warm, rainy, and very humid. In a climate where nothing dries, it’s extremely difficult to deal with wet waste. Not only does it not compost easily, it also releases a toxic liquid called leachate. Engineer RVG Menon says the processing plant didn’t quite take these facts into account when they let the pile of trash build up, untreated.

MENON: The waste produced in Trivandrum or any part of Kerala for that matter, has about 75 to 80 percent moisture. Especially when it is raining, rainwater also falls in it, because of the drizzle, and that increases the quantity of leachate, and they had no facility for treating this much quantity of leachate. So it was overflowing and mixing with the groundwater and then coming into the stream. It was an open stream there, and that stream ends up in the Karamanah river, from which we get our drinking water. So we are also sufferers of pollution - the polluted water is distributed as drinking water and distributed in the city.

SHARMA: Word spread about the dump in Vilappilsala, and soon the village was infamous for its stench. The mountain of trash began to taint every aspect of the villagers’ lives – from land value to marriage prospects.

VILLAGER 4: You cannot sell the land because the factory nearby is creating problems. So no selling and no buying is going on. It’s the first problem. The second problem is the wedding in the near area. Bride and bridegroom - both of them, difficult to marry a girl . They say "where are you living?" "I'm living nearest the factory." "Oh that is very difficult to stay there…" So the wedding is stopped on the way.

SHARMA: Now, the importance of marriage in India can't be overstated - it’s perhaps the single most significant custom for all levels of society. But the trash issue soon became bigger than dashed marriages, and the villagers had had enough of what they call “their suffering.”

So in December 2011, they fought back. Thousands of villagers joined together and completely blocked the roads to the garbage plant. When the garbage trucks trundled in from the city, they had nowhere to go. This went on for days. When the city sent the police, the villagers refused to budge, and the plant was forced to close.

It’s been over two years since garbage has entered Vilappilsala. The city isn’t willing to abandon the plant just yet, but the villagers say they won’t rest until it’s closed for good.

VILLAGER 5: We have only one idea. That the factory is not existing here. We close it, that chapter. One time or two times, no compromise. The countryside people’s are in strong decision. We will not allow the vehicles in Vilappilsala.

SHARMA: While this gridlock festers, the city of Trivandrum has ceased all trash collection – there’s nowhere to put the garbage. Trash piles up in corners around the city. People slyly toss bags off the side of highways, or burn their waste on small streets. The current Mayor of Trivandrum, K. Chandrika, recognizes the plant cannot cope with the scale of waste produced in the city, and proposes shifting some of the burden away from the plant.

CHANDRIKA: We need process only 90 tons of the garbage there. And we are trying to decentralise our garbage to the household level itself.

SHARMA: But she insists that the plant has to reopen and has gone to the courts to force the villagers to stop their blockade.

CHANDRIKA: It is up to the court to consider, the high court considers all the matters. The people should obey the law.

SHARMA: While the villagers of Vilappilsala are firmly opposed to bearing the burden of trash they didn’t produce, the challenges facing the village and city are larger than a blame game.

No one in the country is impervious to India’s mounting waste. But reducing the amount of trash that ends up in the dump would involve serious government intervention through recycling programs, packaging regulations, and innovative approaches to trash management. One new effort in Kerala uses trash as a construction material to build railway platforms. So cities around India are trying, but it’s not working smoothly anywhere, yet.

Engineer RVG Menon treats the little waste he produces in his own yard, but he knows this isn’t possible for everyone.

MENON: So I think a centralized treatment facility is unavoidable in a city like Trivandrum, or in any city for that matter. You have waste collected from the marketplaces, street cleaning and government offices where they don’t have facilities for disposing of waste, so this is the responsibility of the corporation - they have to collect it and they have to have central facilities.

But unfortunately nothing is possible in Vilappilsala now. The people won’t listen to anything. And until Vilappilsala is no longer like this, no other neighborhood will allow this facility in their backyard. So the way out is for the government to find some location reasonably big and in the control of the government, where they operate a model plant with no anxiety and convince the people it is possible to do it this way.

SHARMA: At the moment, India produces 115 million tons of solid waste every day. And by 2030, there'll be 1.5 billion Indians, and half of them will live in cities. So how India tackles its trash is critical. And with population levels rising across the world, this is an issue for all cities that send their garbage away from urban areas. For the sake of the natural and built environment, trash disposal can’t remain out of sight, out of mind for long.

For Living on Earth, I'm Meara Sharma.

[This report was produced by Meara Sharma and Henry Peck]

Related link:

Almirah Radio

[MUSIC: Various/Bombay Dub Orchestra “Mumtaz (The Ornament of Palace Mix) from Traveler 06 (Six Degrees Records 2007)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...from too much waste in a village in India to zero waste in a city in America. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Snarky Puppy: “Flood” from Tell Your Friends (Ropeadope 2011)]

Zero Waste Atlanta

(Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The restaurant and hospitality business can pile up lots of waste if it isn’t careful - everything from left over food to used containers to cooking oil. And to keep all that junk and goop out of landfills, the restaurants, hotels and convention center in downtown Atlanta got together a few years back to create the first zero waste zone in the southeast. Eco activist and restauranteur Laura Turner Seydel joins us now. Tell me Laura, how did the downtown Atlanta Zero Waste Zone get started?

Laura Turner Seydel (Laura Turner Seydel)

SEYDEL: Well, it really came out of the need to create a more sustainable city. We actually lost a conference to a city that was perceived to be greener. So the city of Atlanta rallied to make our city perceived as greener and came up with the zero waste zone.

CURWOOD: The restaurants got involved here. What was done involving the restaurants, and why are they so important?

SEYDEL: Well, first of all, the four parameters that were adopted by each one of the restaurants as part of the convention centers, the arenas, the hotels were: one, all the spent grease was collected to be turned into biodiesel; all of the valuable materials, such as corrugated cardboard, paper, glass, aluminum, plastic, food cans needed to be recycled; all the residual good food would be distributed to the homeless and the hungry based on the good Samaritan laws; and then all the food prep residuals were to be composted. And all of that has been happening. We’ve had record numbers of businesses adopt these parameters and become part of the zero waste zone initiative, and it really grew to other parts of Atlanta and Georgia based on the success that we experienced in downtown Atlanta.

CURWOOD: I know you’re on the board of your dad’s restaurant chain. You call it, what, Ted’s Montana Grill?

SEYDEL: That’s right. We say “eat more, bison.”

CURWOOD: So I imagine you made these changes in your own restaurant beyond, of course, just serving buffalo, right?

SEYDEL: Well, you are so right. In 2002, we opened our first restaurant. We have, actually, 44 now. But we have made a huge commitment as leaders in sustainability for the industry. One of our big commitments is going 99 percent plastic free. And one of my pet peeves has become plastic straws. When I learned that 500 million plastic straws go from our lips to the landfill after one use on each day in the United States, I really became a huge opponent to plastic straws, and we actually have paper straws at Ted’s. We actually put the guy that manufactured paper straws back into business, and now the guy’s a millionaire and has been making paper straws for the cruise ship line industry and other companies that are trying to do what we’re doing and reduce the amount of plastic.

Disposable plastic straws are not on the menu in a “green” restaurant. (Bigstockphoto.com)

But one of the really important things that has evolved out of the zero waste zone and our partnership with the National Restaurant Association - they’ve made a big commitment to sustainability and have produced and put on their website, available to their members, 65 different videos that are how-tos...how to reduce water use, energy use, how to manage recycling and waste, and these are just great ways for restaurants, and really important ways that restaurants are able to reduce the cost associated with operations. And it really is a big deal in a down economy for these small and medium size companies to be able to reduce costs.

CURWOOD: Laura Turner Seydel, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

SEYDEL: Well, thank you, Steve, and we’ll look forward to seeing you soon.

Related links:

- Laura Turner Seydel’s Website

- National Restaurant Association’s greening guide

[MUSIC: The Bad Plus “Seven Minute Mind” from Made Possible (The Bad Plus Music 2012)]

Citizens on the Watch for Hummingbirds

Calliope hummingbirds are the smallest birds in North America (Photo: Dan Tracy for Hummingbirds at Home).

CURWOOD: The changing climate is impacting birds, from the largest of all to the smallest of small - the hummingbird. Hummingbirds are more fragile than many bird species, in part because their fast metabolism requires nearly constant feeding. Geoff LeBaron is a scientist and the director of the Audubon Society’s annual Christmas bird count. He’s working on a citizen science project called Hummingbirds at Home, where people can share their observations, and I called him up in Northampton, Massachusetts to ask him why it’s important to monitor hummingbirds.

Hummingbirds at Home includes an app to add geographic tags and make hummingbird monitoring easier (Photo: Hummingbirds at Home)

LEBARON: Well, what we’re learning, what we’re realizing, is there’s a growing mismatch in the time when the hummingbirds are arriving here from their wintering grounds and the initial blooming of the wildflowers. When they’re first arriving, they’re very energy stressed and need all the nutrients they can get, especially out west; in some areas of the Rocky Mountains, we’re discovering that the initial flowering is happening as many as two, two-and-a-half weeks ahead of when the hummingbirds arrive. They’re actually arriving at the end of that first flowering, and there isn’t anywhere near as much nectar and resources for them available. So we’re concerned about how that will affect, or how that is affecting, their nesting success, and also their long-term survival and their ability to then head south again for the next fall.

CURWOOD: By the way, how far do hummingbirds typically travel when they migrate?

LEBARON: The two furthest species are Rubythroated hummingbirds here in eastern North America, which travels about, back and forth, between most of eastern North America and northern South America. In the west, the Rufous hummingbird actually goes from Mexico, and they bred as far as southeastern Alaska.

A ruby-throated hummingbird, the hummingbird most commonly spotted in the Northeast, hovers above a backyard feeder. (Photo: Cheryl Gayser for Hummingbirds at Home)

CURWOOD: Wow! So what kind of data do scientists have on hummingbird migrations?

LEBARON: There’s a lot of known data and a lot of people studying arrival dates, and where species of hummingbirds are and at what time, and what’s happening to them in terms of vagrant species showing up in the east, which is happening more and more.

CURWOOD: Vagrant?

The Rufous hummingbird follows the Rocky Mountains to migrate from Alaska to Mexico (Photo: Diana Douglas for Hummingbirds at Home).

LEBARON: Vagrant species in terms of ones that actually aren’t supposed to be here in the fall necessarily. In the east, some of these western long distance migrant birds, that end up in the northeast late in the fall, when hummingbirds should have left.

What isn’t known though is what are the interactions between hummingbirds and their nectar sources. And that’s really what the Hummingbirds at Home project is about. We hope to learn, do they have hummingbirds in their yard, and what nectar sources do they have, including do they have a hummingbird feeder. And as you’ve probably noticed this, if you’ve had a feeder up in the past, and don’t get it up in time, your hummingbirds are going to be buzzing around where that feeder was last year saying ‘where’s our feeder this year?’ They’re incredibly good at learning where the nectar sources are in their territory, and they monitor them on a daily basis.

Geoff LeBaron, Audubon scientist and director of the Christmas Bird Count, monitors the hummingbirds in his backyard (Photo: National Audubon Society).

CURWOOD: So you have an app.

LEBARON: We do.

CURWOOD: Let’s see. I set up an account, and I can enter a patch or list a single sighting. So I click ‘patch’ and a timer starts ticking...and when I see a hummingbird?

LEBARON: When you see a hummingbird you can select...there’s a list of species of hummingbirds there. For us in New England this time of year, it’s just going to be Rubythroated, unless you want a lot of birders visiting your yard, in which case you could try to report something else.

Sometimes Allen’s hummingbirds end up in the Northeast in the late fall after they lose their bearings during migration (Photo: Jack Ludwick for Hummingbirds at Home).

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

LEBARON: So here we would just say ‘yes, I have hummingbirds that are Rubythroated’, and then there’s a box for each nectar source that you can check when you see the hummingbird go to that nectar source.

CURWOOD: So with climate disruption, the temperate zones are moving north. What are the odds that we’ll see different kinds of hummingbirds in the northeastern part of the United States?

LEBARON: Especially in the fall, I think that it’s an increasing pattern that we are seeing. The Rufous tend to migrate over land, so they follow the Rocky Mountains down, and then they really have to make a sharp turn to head south, to head down to Mexico. If there’s a weather pattern. - most of our strong weather comes across from west to east across northern North America - those birds will just continue eastward until they actually get here to the northeast.

So we are seeing an increasing number of Rufous hummingbirds. As more and more of these out of season hummingbirds are being banded, we’re realizing there’s an increasing number of Allen hummingbirds as well, in addition to the tiniest bird in North America which is the Calliope hummingbird, which is another long distance migrant hummingbird, and they show up also here in the northeast late.

People without smartphones can also log their data using the Hummingbirds at Home website. Once the scientists begin to analyze the data they will post the results here. (Photo: Hummingbirds at Home).

And we are trying to figure out what the long-term ramifications are. For most of these birds, especially the Rufous and the Calliopes, on any given day, they are actually experiencing sub-freezing temperatures because they breed up high in the mountains in the northern Rockies. So it’s not the temperature that is in their detriment, as much as just the lack of nectar source for them if they get up in the wrong place at the wrong time.

CURWOOD: Your citizen science project, Hummingbirds at Home, this year was a pilot season, but I gather you have a fair amount of data. How many folks have signed up for this?

LEBARON: Last I heard, we had 6,000 or 7,000, people, or as many as 10,000. But we’re hoping there will be quite a bit more than that for future seasons.

CURWOOD: Really, what are your aspirations?

LEBARON: The more the better, really. People as you know, love hummingbirds. And in the long term, what we really hope to do is develop guidelines on what people can do in their yard that will actually enhance the survival and chances of reproductive success for the hummingbirds in the area.

Because of their small size, hummingbirds must feed frequently to fuel their speedy metabolism. (Photo: Lea Foster for Hummingbirds at Home).

CURWOOD: Geoff LeBaron is an Audubon scientist and the spokesperson for the Hummingbirds at Home citizen science project. Geoff, thanks so much for joining us today.

LEBARON: Well, thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: There are more details about the citizen science hummingbird project at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Hummingbirds at Home

- Geoff LeBaron

[MUSIC: David Barrett “Hummingbird” from Music For Acoustic Guitar (David Barrett Music 2006)]

National Moth Week

Female (top) and male (bottom) Automeris io moths. (Wikipedia commons)

CURWOOD: Citizen science is a trend that's spreading. From July 20 to 28, people in 40 different countries as well as the US prowled around at night to celebrate those fluttering denizens of darkness - the moths. There's been moth spotting, and moth slumber parties, as well as lectures and night walks from Bhutan to Belgium and New Zealand to Norway. And reporter Ari Daniel Shapiro has been checking out some of the events here in the US.

SHAPIRO: There are countless animals that have a kind of power over humans that lure us in, that compel us to write mythologies, that make us gaze through a pair of binoculars. Usually the animals are big, charismatic things - like tigers, or pandas. But charisma can come in much smaller sizes too, and trigger just as powerful an attraction. It’s this appeal of the small that turned people out in droves.

MOSKOWITZ: They’re amazing. Let it settle - now you can see those red underwings.

WOMAN: Wow.

KID: Oh, wow, that’s like, awesome.

SHAPIRO: We’re in Frost Woods Park - a patch of green in East Brunswick, New Jersey, and our first of three stops. It’s nighttime - about 9pm. And these couple dozen kids, parents, and neighbors are on the lookout for moths.

MOSKOWITZ: There’s something kinda magical about being out at night with all kinds of biodiversity - everything from the size of a pinhead up to a moth as big as your hand.

SHAPIRO: David Moskowitz is the co-founder of something called National Moth Week. In late July, for an entire week, over 300 hundred moth-inspired events were hosted in every state in the US - except North Dakota...

MOSKOWITZ: North Dakota, where are you?

SHAPIRO: ...and in numerous places around the world – Costa Rica, Gambia, Bulgaria, even the Azores in the middle of the Atlantic.

MOSKOWITZ: There’s always something to find. It’s like a treasure hunt.

SHAPIRO: The other co-founder, Liti Haramaty, says National Moth Week’s intended, in part, to cast aside the view that moths are just a swarm of ugly, winged pests.

HARAMATY: Some of them are as beautiful as butterflies, or even more beautiful than butterflies.

SHAPIRO: Such as the io moth, or Automeris io, Haramaty’s favorite – a bright yellow one with two big black eyespots on its wings. She says that looking for moths can be really rewarding. For one thing, in the US, moths outnumber butterflies by about 15 species to one, not to mention that finding moths at night is pretty easy.

HARAMATY: All you have to do is turn on a light at night, and they’ll come to you - you don’t have to go look for them.

[GENERATOR POWERS UP]

SHAPIRO: Two and a quarter miles above sea level, perched atop the continental divide of Cottonwood Pass in central Colorado - our second stop - a generator roars to life, powering a bright light. It’s nighttime, and the faces of a dozen people light up in its soft blue glow. Most of them are lepidopterists - who study moths and butterflies by profession. Someone’s unrolled a screen in front of the halogen - to catch the moths flapping through the cold mountain air.

LANDRY: It’s a hepialid - [Korscheltellus] gracilis. For the first time in 30 years.

ADAMS: Hold on just a second - it looks like there’s something much bigger on the other side. Oh yeah, here we go. Here’s a noctuid. I think it’s a Lasiestra. It’s still kicking a little bit.

Madagascar Sunset moth (Chrysiridia rhipheus)

(Photo: Didier Descouens-Wikipedia commons)

SHAPIRO: Jean-François Landry, who drove here from Quebec, James Adams, who flew in from Georgia, and the rest of the group are collecting these high elevation moths.

LANDRY: In terms of unknown diversity – new species, this is kind of the frontier.

SHAPIRO: By far the youngest person up here is Megan McCarty. She’s 16, from Indiana, and is an avid lepidopterist in the making.

M. MCCARTHY: Oh, this is just a killing jar. I basically put moths in here, and I have poison in here. And then I’ll put them in my collection.

SHAPIRO: Her dad, David McCarty, has tagged along too.

D. MCCARTHY: I’m a supporter of moth love. I like to see the action, but it’s just something that Megan does. I like birds.

SHAPIRO: Our last stop is in the middle of the island of Oahu, in Hawaii up past a series of pineapple plantations on a lush path in the Ewa Forest Reserve. It’s usually closed to the public. That’s because this trail runs along a knife-edge ridge, only 25 feet wide, with a drop on either side. But Cynthia King, an entomologist from Hawaii’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife – is keeping careful watch over the 17 people who’ve assembled in the fading daylight.

KING: Everybody else have their stuff - water bottle, flashlight, rain jacket? Awesome.

[GUST OF WIND]

SHAPIRO: A strong gust of wind sweeps across the ridge. Wind’s not good for spotting moths - it doesn’t allow them to settle on the lit-up sheet.

But it turns out it was ancient winds that blew most of Hawaii’s moth species - 850 and counting - from the mainland out to its islands. That’s why the moths in Hawaii tend to be smaller than the ones you’d find in North and South America. Little moths can travel much farther on the wind.

Finally, the breeze settles down, and a single moth emerges out of the darkness. A tiny, mottled flutter.

KAWELO: Oh, ooh.

[BAG OPENING]

SHAPIRO: Kapua Kawelo, who’s out here with her two kids, gently lowers the moth into a baggie.

[FLUTTERING]

KAWELO: Hey, there’s a moth over here. You guys wanna check it out?

SHAPIRO: Cynthia King comes over to investigate.

KING: This is a little sphinx moth.

SHAPIRO: Or Hyles wilsoni perkinsi. The group spots another several moths but before long, it’s time to pack it in.

They head back, walking carefully along the ridgeline. And they talk softly about searching for such small treasures beneath the night sky. Their headlamps twinkle along the path like a constellation of slow moving stars.

For Living on Earth, I’m Ari Daniel Shapiro.

CURWOOD: Our story about National Moth week comes from the series “One Species at a Time," produced by Atlantic Public Media, with help from The Encyclopedia of Life.

Related links:

- Encyclopedia of Life

- National Moth Week

-

[MUSIC: Anthony Olinger “Moth” from Dance Of The Insects (Anthony Olinger Music 2012)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Poncie Rutsch, Erin Weeks, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and check out our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Ren Stevenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth