April 12, 2013

Air Date: April 12, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Green Team in the Hot Seat

View the page for this story

Two of the nominees for posts in President Obama’s Green Team recently faced confirmation hearings in the Senate. Ernest Moniz, nominee for Secretary of Energy, and Gina McCarthy, nominated to head the EPA, answered questions on a number of difficult environmental questions. (06:05)

Who Rules the Rules of the EPA?

View the page for this story

The EPA will be President Obama's primary tool for slowing climate change in his second term. But the next EPA chief faces obstacles from inside the White House itself, at the Office of Management and Budget. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Georgetown law professor Lisa Heinzerling about this little known barrier to environmental regulation. (07:40)

Science Note/New Organs On Demand

/ Naomi ArenbergView the page for this story

This month, University of Iowa researchers announced a breakthrough in bioengineering. In this week’s Note on Emerging Science, Naomi Arenberg reports that the first multi-arm bio-printer might be able to create new organs. (01:55)

Turning On Tidal Power

View the page for this story

In honor of Earth Month, we are updating some of our favorite stories. This week, Jeff Young reports on the potential of ocean tides to create electricity to power the grid. Then host Steve Curwood learns from Ocean Renewable Power Company founder Chris Sauer how the tidal power experiment is working out. (09:30)

BirdNote® How Birds Sing So Loud

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Evolution has given the Carolina Wren one of the most impressive songs in the forest. BIRDNOTE®’s Michael Stein explains how this tiny bird can sing so loud. (02:00)

Secrets of the Forest Floor

View the page for this story

When we think about carbon sinks, we usually picture dense forests packed with big trees. But new research from Sweden suggests that tiny fungi in the soil may deserve a little more credit for slowing global warming. Host Steve Curwood talks mushrooms with ecologist Karina Clemmensen. (06:00)

The Future of Robots

/ Lisa RaffenspergerView the page for this story

Robots are no longer confined to the world of science fiction. They currently play important role in industry, medicine and the military. Lisa Raffensperger from IEEE Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation special "Life in 2030" reports on the future of robots in our daily lives. (10:00)

Rod Clark Essay - The Ten Minute Brook

/ Rod ClarkView the page for this story

Writer Rod Clark tells us about a sudden, short lived surprise the melting winter snows brought him in a meadow on his Wisconsin farm. (02:25)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

On the east coast of the big island of Hawaii the dramatic Akaka Falls plunge more than 400 feet down into a gorge. But follow a narrow path through the jungle … and you’ll find a much smaller cascade feeding a stream beneath a wooden bridge, sending up a mist of fine droplets. Toby Mountain recorded this soothing scene for his CD, A Week in Hawaii.

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: Lisa Heinzerling, Naomi Arenberg, Chris Sauer, Karina Clemmensen

Reporters: Jeff Young, Lisa Raffensperger, Rod Clark

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. President Obama's picks to head the Energy Department and the EPA face Senators on Capitol Hill, and the EPA itself is in the hot seat.

BARASSO: The EPA is making it impossible for our coal miners to feed their families - you know how many more times, if confirmed, will this EPA director pull the regulatory lever and allow another mining family to fall through the EPA's trap-door to joblessness, to poverty and to poor health.

CURWOOD: We assess the prospects of the nominees. Also, how to build robots to operate in our

world.

HONG: If a robot needs to live with us in an environment designed for humans, then I claim the robot needs to have size and shape of a human. So if the robot is not a humanoid form, it won’t be able to navigate an environment designed for humans.

CURWOOD: We'll have that story and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic smoothies, yogurt, and more.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Green Team in the Hot Seat

President Barack Obama announces the nominations of, from left, Ernest Moniz as Energy Secretary, Gina McCarthy as Environmental Protection Agency Administrator, and Sylvia Mathews Burwell as Director of the Office of Management and Budget, in the East Room of the White House, March 4, 2013. Official White house Photo

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Four months into his second term President Obama is still building his green team. Sally Jewell has finally been confirmed as Secretary of the Interior, but the President’s picks to run the Environmental Protection Agency and the Energy Department are waiting for Senate approval. Secretary of Energy-designate Ernest Moniz was President Clinton’s undersecretary of energy, and the experience showed at his confirmation hearings on April 9.

MONIZ: The President has advocated an all of the above energy strategy, and if confirmed as Secretary I will pursue this with the highest priority. As the President said when he confirmed my nomination 'we can produce more energy and grow our economy while still taking care of our air, water, and climate.' The need to mitigate climate change risks is emphatically supported by the science and by the engaged scientific community. DOE should continue to support a robust R and D portfolio of low-carbon options, and to advance a 21st century electricity delivery system.

CURWOOD: When the MIT Professor was asked to introduce his family to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Moniz had some numbers.

MONIZ: I’d start with my wife of 39.83 years, Naomi…

Ernest Moniz, nominee for Secretary of Energy (photograph: Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

CURWOOD: Minnesota Democrat Al Franken challenged the professor's arithmetic.

FRANKEN: Dr. Moniz thank you for being with us. You said you’ve been married 39.83 years, may I remind you you’re under oath. Is your anniversary June 10th.

MONIZ: June 9. That’s in the rounding area – err error.

FRANKEN: All right, well we’ll have to consider.

CURWOOD: It was a light moment in a session that mostly dealt with dark matters. Professor Moniz is a nuclear physicist and Nevada Republican Dean Heller grilled him about the stalled Yucca Mountain nuclear waste depot.

HELLER: Yucca Mountain was plagued with problems, included falsified science, and design problems. Given this, it's no wonder that Nevadans don’t trust the assertions that Yucca Mountain is safe. The people in Nevada deserve to be safe in their own back yards. No amount of reassurance from the Federal government will convince us that Nevada should be the nation’s nuclear waste dump.

CURWOOD: The chairman, Democrat Ron Wyden of Oregon, complained about the Cold War era atomic weapons plant in Hanford, Washington, where radioactive waste has been leaking.

Ron Wyden, chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (photo: United States Senate)

WYDEN: As Congress works to address nuclear waste, it’s important that the Department take responsibility for contaminated waste sites like Hanford. It’s flatly unacceptable that the department still has no viable plan to clean up the waste on the Columbia River half a century after the contamination occurred and more than a decade since Doctor Moniz served as undersecretary of energy.

CURWOOD: The Senator wanted reassurance that, if confirmed, Ernest Moniz would act. The professor replied that, were he confirmed, he would. By and large he had a warm reception, and his nomination is expected to sail through. A couple of days later EPA nominee Gina McCarthy faced the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee.

Gina McCarthy, nominee for the head of the Environmental Protection Agency (photograph: EPA)

MCCARTHY: I'm deeply honored that President Obama has nominated me to lead the EPA. Having spent my career in public service I know of no higher privilege than working with my colleagues at EPA, with Congress, and our public and private partners to ensure that American families can breathe clean air drink clean water and live learn and play in safer healthier communities.

CURWOOD: The committee gave the nominee a cordial reception, but there was plenty of criticism of the agency she's been tapped to head. Some Republican Senators questioned the reality of climate science, and complained that EPA regulations are destroying industries and costing jobs. Here's John Barasso of Wyoming.

US Senator John Barasso (R-WY)

BARASSO: I'm not sure whether the nominee before us today is aware personally of so many folks who have lost their jobs because of the EPA, and a role I believe it is taking now, which is failing our country. The EPA is making it impossible for coal miners to feed their families. How many more times if confirmed with this EPA director pull the regulatory lever and allow another mining family to fall through the trap door to joblessness, to poverty, and to poor health. Regulations and proposed rules on greenhouse gasses, coal ash, mercury emissions and industrial boilers have led to the closing of dozens of power plants in the US, costing our country thousands of jobs.

CURWOOD: But Independent Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont was having none of that argument.

US Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT)

SANDERS: Really this is not a debate about Gina McCarthy. Senator Barasso made it very clear what the debate is about. It is a debate about global warming. And weather or not we are going to listen to the leading scientists of this country who are telling us that global warming is the most serious planetary crisis that we and the global community face and weather we are going to address that crisis in a serious manner. And in essence what Senator Barasso has just said is 'no'. He does not want the EPA to do that. He does not want the EPA to listen to science. What he wants is for us to continue doing as little as possible as we see extreme weather disturbances, drought, floods and heat waves all over the world take place. So, let me go on record and say I want the EPA to be vigorous in protecting our children and future generations from the horrendous crisis we face from global warming.

CURWOOD: Bernie Sanders of Vermont. Still, despite the heated rhetoric, even GOP members said they are looking forward to working with Gina McCarthy. And she too is expected to win confirmation.

Related links:

- Department of Energy

- Environmental Protection Agency

[MUSIC: Captain Beefheart “When I See Mommy, I Feel Like A Mummy” from Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) (Warner Bros. 1978)]

Who Rules the Rules of the EPA?

Lisa Heinzerling, Law Professor at Georgetown University (photo: Georgetown)

CURWOOD: Well, assuming Gina McCarthy is confirmed, she'll head up the agency perhaps most responsible for delivering on President Obama’s promises to address climate change and rein in carbon emissions. But the next EPA head could face a surprising and continuing obstacle inside the Obama administration itself, at the Office of Management and Budget. Lisa Heinzerling, a former EPA official who is now a Law Professor at Georgetown University has written about OMB's sometimes obstructive role in environmental rule-making. She joins us now from Washington DC. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HEINZERLING: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: First off, please explain to me what is the Office of Management and Budget, and how does it impact the Environmental Protection Agency's ability to promulgate regulation?

HEINZERLING: The Office of Management and Budget is an office within the White House famous mostly, as the name implies for managing budgetary issues. And it also has within it a little office called the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. People who know this office, know it by its acronym OIRA. And for quite a few years now, that office OIRA, has reviewed all of the major regulations that come out of administrative agencies and has had the authority to disapprove of rules that come out of administrative agencies. Most people don't know this, but it's a very powerful office.

CURWOOD: I gather this process got going during the Reagan administration under the tutelage of David Stockman. To what extent has this been an attempt to consolidate control in the Office of the President?

HEINZERLING: Well, I think to a large extent, it has. One of the striking things people have noticed about this dynamic is that most presidents, regardless of party, have seemed to clamped down tighter and tighter on administrative agencies and to centralize power more and more within the White House itself.

CURWOOD: So what's the criteria that OMB uses when it judges EPA rules?

HEINZERLING: Well, it's a little bit hard to tell. The first thing I would say is that at least in this administration many rules have gone to this office for review and have never come back. They are stuck there for years and years and there's no explanation about why that is. And so it's a little bit hard to evaluate the criteria by which they're being judged to or to describe the criteria when you don’t know why the rules are stuck. The second point is that OMB tends to look at rules through the lens of cost-benefit analysis. That's what its governing executive orders provide, and that's been its bent over the years. So to some extent at least we can speculate that some of the rules are stuck because they don't pass some of these cost-benefit analysis.

CURWOOD: What a second, Professor, as I understand, the law for a number of EPA regulations such as stuff under the Clean Air Act, cost-benefit analysis isn't allowed. Do I have that right?

HEINZERLING: You do have that right. That's why the process is so puzzling and even troubling. Some of the most important provisions of the Clean Air Act actually don't allow cost-benefit analysis. The Supreme Court held unanimously an opinion by Justice Scalia no less that EPA could not consider cost-benefit analysis in setting those standards, and yet strikingly the one rule that President Obama has returned to an agency in this administration - with a public explanation - was a rule set under that provision of the Clean Air Act. That was the standard for ozone.

CURWOOD: Ozone pollution? You're talking about smog, right?

HEINZERLING: Yes, and so the troubling message that this sends is the possibility that cost-benefit is being used to evaluate rules even where it's legally forbidden.

CURWOOD: What did the President say in his message of transmittal saying that he was

sending the ozone back to EPA. Did he mention cost-benefit?

HEINZERLING: That's so interesting. He actually said...he cited regulatory burden and regulatory uncertainty and the economic conditions in the country. Sounded an awful lot like the consideration of costs to me at least.

CURWOOD: Ordinarily one would want to think that one should look at the cost of a regulation. Explain why cost benefit analysis would be a problem in such a case?

HEINZERLING: Yeah, I think it's tricky to figure out exactly what the benefits of environmental regulation are. It's hard to quantify them. It's hard to figure out how many people might die or fall ill or go to the hospital or miss work or school if pollution stays at current levels. And then it becomes even trickier to figure out how much those things are worth in dollar terms. These are kinds of questions that have dogged economists for many, many years. And I'm not sure we have good answers to them yet. The worry is cost-benefit analysis will skew the process against environmental rules. It'll almost never tell us to do a rule that we otherwise wouldn't want to do. They'll often come in and say or suggest that we shouldn't engage in rules that probably seemed like a really good idea. Rules on water pollution, for example, tend to fare very poorly in cost-benefit analysis. Let me just say again though, one of the predominant points worth noting about this process right now is that we just don't know why rules are getting stuck in the White House. It could be cost-benefit analysis, or it could be something else entirely. We just don't know.

CURWOOD: What specific issues do you think this will impact in the remainder of President Obama's term?

HEINZERLING: It will, I believe, absolutely affect rules on climate change. It'll affect rules on energy efficiency even at the Department of Energy. It'll affect large air pollution rules like air quality standards for pollutants. It will affect large rules on water pollution, rules on toxic chemicals in so far as the agencies issuing rules - and rules that the White House deems as major. It affects everything he does.

CURWOOD: There's much controversy over the CO2 rules. What you're saying makes me wonder if one should be concerned the White House again will intervene in what the EPA is trying to do in putting forth rules about the amount of greenhouse gases that can come from power plants and other places.

HEINZERLING: Well, I think that given the way the administration has handled regulatory policy so far, there's no question but that any rules on greenhouse gases from the EPA will go to the White House for review. And in that process they may well be either substantially changed or could be rejected altogether.

CURWOOD: And this will be in public view?

HEINZERLING: Not necessarily. I would hope that something so important would be more transparent than some of the other processes I've described. But I can't say that it will be given the track record. I think in an administration that has so committed to transparency - and I think really intense transparency in many domains - I think it's striking that in the domain of regulatory policy they've had such closely held secrets.

CURWOOD: Lisa Heinzerling is a professor of law at Georgetown University. Thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

HEINZERLING: My pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- Lisa Heinzerling’s faculty page

- Office of Management and Budgets

- Lisa Heinzerling’s article criticizing OMB in the Yale Journal on Regulation

CURWOOD: Coming up...Scientists say it won't be too long until If you need a new organ, they can simply print one. That's just ahead Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Bonobo “Antenna” from The North Borders (Ninja Tune 2013)]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ernest Ranglin: “Black Disciples” from Below The Bassline (Island Records 1996)]

Science Note/New Organs On Demand

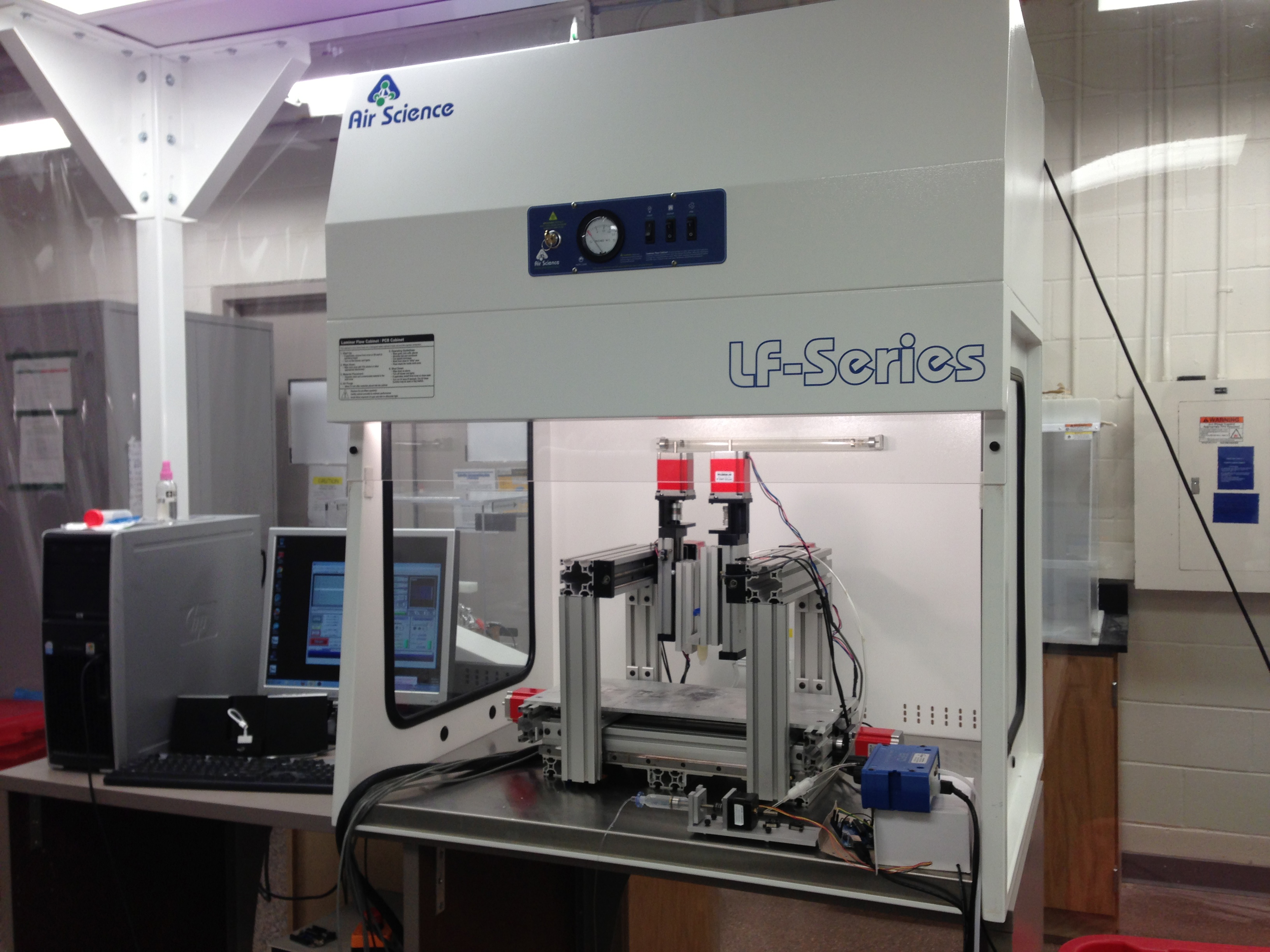

The multi-arm bio-printer (photograph: Yin Yu, University of Iowa)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Just ahead, tides ebb and flow like clock-work twice a day - but that doesn't ensure smooth sailing for tidal power. First here's this note on emerging science from Naomi Arenberg.

[MUSIC]

ARENBERG: A breakthrough in printer technology could make it possible for scientists to manufacture human organs in the laboratory. These bio-printers rely on mechanisms that resemble the old dot-matrix system, except that, instead of spraying dots of traditional ink, they spray “bio-ink.” That’s a solution of living cells and a thick liquid biomaterial that helps the cell grow into living tissue, once printed onto a surface. A container of this “bio-ink” is fastened to the end of a printer “arm,” which scans back and forth to print a row of dots on each pass.

The bio-printer is not a new idea, but now a new design by University of Iowa engineers enables specific tissue cells to be printed alongside blood vessel cells so fast, it’s almost simultaneous. This means that those tissue-specific cells can grow and develop with their own blood vessels, ensuring a flow of nutrients to the fragile, young tissue and hastening its development.

What makes this possible is a double-arm printer. Until now, printers had only one arm, which laid down only a single line of bio-ink. The research team hopes to print human organs for transplant within five to 10 years. One of the first of these could be a pancreatic organ that could be implanted anywhere in the body to regulate glucose level. Now that people are living longer, the demand for replacement organs is far out-pacing supply. Perhaps the laboratory will be able to help fill the gap.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Naomi Arenberg.

Related links:

- The University of Iowa’s newsletter about the bioprinter with a video

- Do-it-yourself bioprinter

- Ted talk about printing a human kidney

- Link to article, “Development of a valve-based cell printer for the formation of human embryonic stem cell spheroid aggregates.”

Turning On Tidal Power

Tidal generator (photo: Jeff Young)

CURWOOD: In honor of earth month which we celebrate for the whole of April, we're bringing you updates of some of our favorite stories. Back in July of 2011, we looked at harnessing the power of ocean tides to generate electricity. Jeff Young went to Maine to bring us this report.

YOUNG: The barge-like craft moored to a dock in Portland, Maine, looks like some modern version of a sternwheel paddleboat. Hydraulic arms hold a massive cylinder of blades ready to go in the water. But this boat isn’t built for speed, it’s built for power—tidal power. It’s the creation of Chris Sauer and his Ocean Renewable Power Company.

SAUER: This is our baby, this is the Energy Tide 2. This is the largest ocean energy device ever deployed in U.S. waters.

YOUNG: Let’s have a look.

SAUER: Come aboard!

YOUNG: The Energy Tide 2 is normally anchored near Eastport, in an arm of the Bay of Fundy called Cobscook Bay. Sauer towed it to Portland for a national convention on ocean energy. He shows me to the boat’s business end, the high tech composite blades curved inside a turbine generator unit, or TGU.

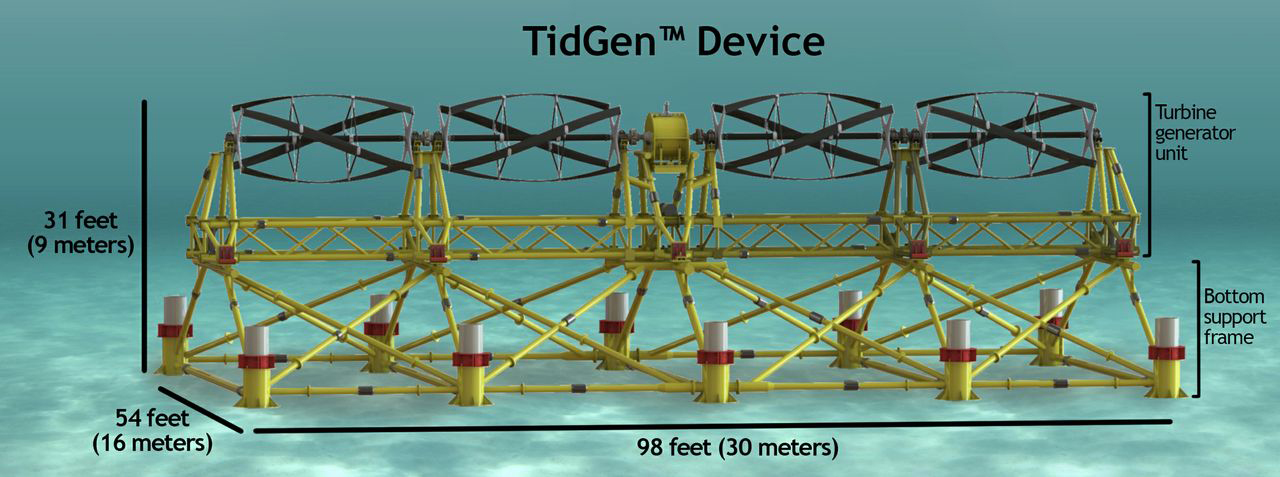

The TidGen tidal generator. (Photo: Ocean Renewable Power Generation)

SAUER: When it’s fully deployed it’s directly under this axle right here. And it’s about 15 feet from the top of the water to top of the TGU, and then it’s locked into position and it just sits there. And as the tidal currents come it starts to generate electricity. And then of course the tide reverses and comes the other way and does same thing. On ac average basis we’re generating about 18 to 20 hours a day.

YOUNG: A small cabin crowded with electronics and monitors converts the power and keeps track of what’s happening underwater. The unit can generate 60 kilowatts of power and that’s been going to a coast guard station, the country’s first federal facility to use tidal power. But primarily, this is a research project. Sauer says in a year of operation it’s shown virtually no impact to fish or other marine life, and it’s proved that the tides can predictably generate power that could be plugged into the grid. Now Sauer wants to scale up.

SAUER: The next step is our turbine generator unit is going to get a little bigger, instead of two turbines it’s going to have four turbines. It’s going to be about twice as long but it’s going to put out three times the power. So instead of a design capacity of 60 kilowatts it will be 180 kilowatts. And we hope to get that in the water and connected to the grid by the end of the year. That’s our plan.

Tidal generator out of the water (Photo: Ocean Renewable Power Generation)

YOUNG: Sauer says the project also proved tidal power can generate jobs. The company has provided jobs for 100 people in Maine, people like Darrell Speed who had been laid off.

SPEED: Honestly I was at the stage where I was going to have to look to go outside of Maine. I was born and raised here, wanted to stay here, but you know it was coming down to that.

YOUNG: That’s when Speed saw an ad for ocean renewable power. He had no idea what it was about.

SPEED: Well quite frankly I didn’t care at the time I needed a job. Like I said, I wanted to stay in Maine. But since I’ve gotten here this company, you know, it’s a company about creating jobs but also a company about creating a sustainable energy resource for the United States. And it’s renewable. The tides go, ebb and flood every day you can set your watch by it. Now will we be 100 percent able to replace all our energy resources? No. But we’re part of the answer. A big part of the answer.

CURWOOD: Well, it's a couple of years later - and that's about when the company hoped it would be feeding tide-generated power to the grid. So we contacted Chris Sauer, the President of Ocean Renewable Power Company again, to find out if he made his deadline of getting plugged in by the end of 2011.

SAUER: Well, we didn't quite make that schedule, but we did get it connected to the grid. In fact, September 5 of 2012 we delivered the first power into the grid from any kind of ocean energy project, whether offshore wind, wave or tidal anywhere in the Americas other than a project in Nova Scotia that involved a dam.

CURWOOD: So a tidal cycle is about 24 hours. How much of that period of time are you able to generate power?

SAUER: We're actually generating on an average basis maybe 16 to 18 of the hours in a day.

CURWOOD: Now, I understand that you've got plans to expand and put more title generators in the Bay of Fundy in Maine. Tell me about that please.

SAUER: We were able to negotiate a long term 20 year power purchase agreement, which means we secured the market at a attractive price for our power to build out the project in Downeast Maine - eventually up to five megawatts which we intend to do over the next four, five years.

CURWOOD: How many units will you have?

SAUER: Well, that'll be roughly 18 to 20 additional turbine generator units, we call them ,TGUs.

CURWOOD: Now, of course the tides are one source. What about tidal rivers?

SAUER: Well, rivers...any kind of moving water...we have a...what's called RivGen power system which is a much smaller version and it's really designed to be installed in remote communities that have what they call microgrids, typically powered by diesel generators and this is a system that we essentially can tow up river that deploys itself. We simply ballast it. Our first project is going in a year from this summer in a little village in Alaska called Igiugig. So that's very exciting.

CURWOOD: And for folks wondering what's novel, of course, no dam required.

Chris Sauer and his company’s Energy Tide 2, which was developed with some help from the federal government. Sauer hopes the Dept. of Energy will continue its modest support of tidal power. (Photo: Jeff Young)

SAUER: No dam required, and nothing visible from the surface. Everything is below the water so we like to tell people the view before we install the project is exactly the same view you see after.

CURWOOD: Chris, back in 2011 you were concerned about the funding for tidal energy projects. How's that going in, and what's going on in terms of federal backing for your research installation?

SAUER: First of all, the project we have installed now could not have been done without significant involvement of the US Department of Energy. We were able to secure on a competitive basis a $10 million dollar grant for this project, which really allowed us then to raise the private capital. But in general, the mood in Washington, DC, is to defund R&D, particularly for new things like tidal or wave. And so we've been battling that, the amount of money that is made available, for instance, DOE to bid out on a competitive basis is a pittance. It's a few million bucks compared the money made available for other things like nuclear or “clean coal”. It's really miniscule.

CURWOOD: When do you get to break even on this?

SAUER: Assuming the growth scenario where we're able to attract capital, we as a company will be at a break even point in about three years. In terms of cost of electricity, our projections are showing by 2020 or so, we are going to be competitive with virtually any new sources of power. If you look out into that timeframe it looks very good. The issue is how do we get from here to there.

CURWOOD: So give me the back of the envelope calculation as to what the potential for tidal power is in United States? If we were to tap, you know, the obvious and sort of the easier places to do, how much of our power could we get from tidal energy?

SAUER: There's estimates that say it could be ultimately 15 or 20 percent of the total demand for electricity in United States.

CURWOOD: Let me guess there are other countries around the world that are grabbing this technology and running with it? Do I have that right?

SAUER: You're right. In fact, our competition is really for the most part over in Europe. One of the things that's happened there was early on there was significant government involvement in terms of subsidies to get people going. And then some of the European industrial companies people like Siemens and ABB and others have now invested in those European companies that have projects in the water. Although honestly, we've kind of caught up with them, but the problem is now they've gained a significant capital and human resources and this is not happening in the US. We're in a David and Goliath dilemma here because we're going up against the big boys and we're not that big.

CURWOOD: You know, I think I've heard this story before. I think it's called wind energy. I mean we develop the turbines, but the Germans make and sell them now.

SAUER: Yes. We started out in the 70s pioneering and in the end we kind of lost patience and interest. Next thing you know the wind industry comes back in the 90s and it's...most of it is being built by companies from Europe. So I hope this doesn't happen, but it looks like that maybe where this all headed, which is unfortunate.

CURWOOD: Did you ever think when you were a boy playing at the seashore that you would be harnessing all those waves?

SAUER: Well, it's funny. I'm from Illinois, central Illinois, Peoria, Illinois. I didn't even see an ocean until I was in my 20s. So I didn't dream about that because I had a hard time conjuring up what the heck the seashore looked like. But the thing that was compelling at first was almost 70 percent of the world is covered in water. And what I didn't know at the time, is 70 percent of the electricity in the world was within 200 miles of an ocean. And so, if you can somehow put those two things together - excuse the bad pun – but it could be a sea change in how electricity is generated and distributed.

CURWOOD: Perhaps it will play in Peoria.

SAUER: It will play in Peoria.

CURWOOD: Chris Sauer is the President of Ocean Renewable Power Company. Thank you so much, Chris.

SAUER: Thank you. It was a pleasure.

Related links:

- Watch a Video About TidGen

- Listen to the Original Story

- Oceans Renewable Power Company

- Ocean Renewable Energy Council

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE® THEME]

BirdNote® How Birds Sing So Loud

Carolina Wren on a branch (photograph: Ken C Schneider)

[Written by Bob Sundstrom]

CURWOOD: Evolution is a wonderful thing - creating the most weirdly beautiful, ingenious and unlikely creatures. In the beautiful camp there are, of course, many, many birds. But don’t look for showy feathers or glorious colors to distinguish the subject of today's BirdNote®. Here's Michael Stein to explain.

[CAROLINA WREN SONG]

STEIN: When a Carolina Wren tips back its head and sings, something remarkable happens. A Carolina Wren can sing so loudly that you almost have to shout to be heard over its song.

Wrens aren’t the only small birds with big voices, but they are the best known for this ability. How can a bird like a Carolina Wren, all of five-and-a-half inches long and weighing only as much as four nickels, produce so much sound?

The Carolina Wren has one of the loudest songs out there (photograph: Ken C Schneider)

The answer lies in the songbird’s vocal anatomy. Unlike you and I, who create sound from the larynx way up at the top of our windpipe, a bird’s song comes from deep within its body. Birds produce song in a structure called the syrinx, located at the bottom of the windpipe where the bronchial tubes diverge to the lungs. The syrinx is surrounded by an air sac, and the combination works like a resonating chamber to maintain or amplify sound.

Evolution has given birds a far more elaborate sound mechanism than it’s given humans. Where we wound up with a flute, songbirds got bagpipes.

I’m Michael Stein.

[MUSIC: Brad Mehldau “The Falcon Will Fly Again” from Highway Rider (Nonesuch Records 2012)]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Sample: “Cannery Row” from Carmel (UMG Records 1979)]

[MUSIC: Brad Mehldau “The Falcon Will Fly Again” from Highway Rider (Nonesuch Records 2012)]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joe Sample: “Cannery Row” from Carmel (UMG Records 1979)]

CURWOOD: To see some photos of those shrill Carolina Wrens singing their hearts out, flit on over to our website LOE.org.

[Bird songs for BirdNote come from The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Today’s show brought to you by The Bobolink Foundation. For BirdNote, I’m Michael Stein.

###

Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Carolina Wren song [128927] recorded by Gerrit Vyn.

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2013 Tune In to Nature.org April 2013 Narrator: Michael Stein

ID#

sound-17-2013-04-11 sound-17}

Related links:

- The story at BirdNote®

- The official BirdNote® website

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988. Or write to PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts 02199. Our e-mail address is comments@LOE.org. That's comments@LOE.org. You can hear our program anytime on our website or get a download of the audio to listen when you want at LOE.org.

Coming up...a secret of the trees is revealed in some down-to-earth research to understand global warming. Stay tuned for more at Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Secrets of the Forest Floor

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. If you hear the words "carbon sequestration", you might well think of dense forests filled with mighty trees. But new research reported in Science magazine suggests that tiny fungi in the soil may deserve a little more credit for fighting global warming. Ecologist Karina Clemmensen of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala joins us now via Skype to discuss her fungi research. Welcome to Living on Earth.

CLEMMENSEN: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So before your research, what was the thinking on the mechanism for carbon sequestration in forests?

CLEMMENSEN: Yes, so the way people think about it is that carbon enters the soil through litters on the soil surface. So like needles and leaves and branches fall to the soil surface. And then after some decomposition the remains that stay behind accumulates as humus as we call it in forest soil.

Marasmius species are common litter decomposers. (photo: K Clemmensen)

CURWOOD: Your research suggests that the fungi in the soil play a much larger role. Can you explain that for us?

CLEMMENSEN: Little bit simplified, there's two major groups of fungi for forest soil. So there's the fungi working with the leaves that are falling on the soil surface. That's free living saprophytic fungi? So they basically release carbon out of organic material. And then there's the other group of fungi which live in symbiosis with the tree roots.

CURWOOD: What are these fungi called?

The white structures in the soil are visible mycorrhizal fungal structures on the roots tips (mantles) and fungal mycelium extending from the root tips into the surrounding organic soil. (photo: KE Clemmensen)

CLEMMENSEN: Mycorrhiza fungi. They sit on the tree roots and receive carbon directly from the tree, which makes carbon into photosynthesis. And they use that carbon to grow in the soil and produce biomass. And in return, as part of the symbiosis, they return nutrients and water to the tree. So they basically have the capacity to add carbon to the soil at depth.

CURWOOD: So the tree harvests the sunlight for the fungi, and the fungi does the processing to sequester the carbon.

Mycorrhizal fungi on the root of a birch (photo: Karina Clemmensen)

CLEMMENSEN: Um hum.

CURWOOD: So what do these fungi look like?

CLEMMENSEN: Yes, as many of the mushrooms that you know from the forest - like chanterelles and different other edible mushrooms that you see. But that's some that you see there, like the apple on the apple tree. The rest of the fungus is living like small threads in the soil. But if you look closely on the root tips of the tree, you can see that the tips are normally rounded, and they can have different colors - and that's the fungus that form those structures. It can be completely black or some are yellow and you can see hair structures extending from the root tip.

Amanita muscaria, a mushroom formed by different fungi that live in ectomycorrhizal symbioses with trees (photo: KE Clemmensen)

CURWOOD: How much carbon are they adding, do you think?

CLEMMENSEN: So this is kind of the major finding here. So this mechanism of the mycorrhiza fungi to grow in the soil has been known for a long time, but here we're able to quantify how much carbon they actually add - more than 50 percent, 50 to 70 percent of the carbon that is currently stored in the soil is derived from the root rather than from above ground litter.

CURWOOD: Tell me, in general, how important are boreal forests to carbon sequestration around the world?

The study was conducted on 30 islands of different sizes in the two large lakes, lake Uddjaure and lake Hornavan, near Arjeplog in N Sweden (photo: A Bahr)

CLEMMENSEN: If you consider the boreal forest, the biome, together with the Arctic biome, they actually contain a third of the carbon stored in soils globally. If you consider the boreal forest only, it's 16 percent of the carbon stored in soil globally.

CURWOOD: Now, are the fungi working in the Arctic area as well?

CLEMMENSEN: Yes, definitely. We have the same major groups of fungi, but there we have a transition of more dominance of Ericacoid plants like heather plants. They associate with the so called mycorrhiza fungi. And definitely we think that those fungi have an equally big role in carbon sequestration in those areas.

Cortinarius armillatus forms mycorrhizal symbiosis with roots of birch trees (photo: KE Clemmensen)

CURWOOD: So what needs to be done to keep fungi happy? In other words, how does your research shift how we should think about the way we should be managing forests?

CLEMMENSEN: The study we present here is only done in natural forests. It's a long age gradient with forests ranging from 100 years to over 5,000 years. So we have not addressed the question of how to manage forests really. But from this grading we can say that if we leave a forest undisturbed for more than 1,000 years, several thousand years, then it continues to suck in carbon into the soil.

CURWOOD: Ah ha, because people have been saying, look, a tree, once it gets to be full mature size, it's not taking up any more carbon - be almost better to cut it down and plant a new tree. But you're saying no.

Cantharellus tubaeformis, mushrooms formed by different fungi that live in ectomycorrhizal symbioses with trees (photo: KE Clemmensen)

CLEMMENSEN: Yes, maybe the story for the soil is a bit different, right? So we have to consider these processes in the soil more. And definitely when you cut down the tree, then the mycorrhiza fungi will die. And that would leave this other group of fungi, the free living saprotrophs that I talked about living in remote...normally living in the litters, fresh litters in the soil surface. So they could potentially move down and start decomposing more of the stored carbon. A general thing to say here would be, OK, clear cutting in forest management would probably not be good for carbon sequestration.

CLEMMENSEN: Karina, what do you hope comes out of your research?

Karina Clemmensen photographing fungi (photo: A Bahr)

CURWOOD: I hope modelers creating predictive models of future carbon balances and so on would consider this different pathway, and try to create response functions of the two different pathways - the litter and the root derived carbon - because those two pathways might react differently through forest management and climate changes. So it's important to describe them as two different ways of carbon to enter the soil.

CURWOOD: Karina Clemmensen is a researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala, Sweden. Thank you so much for taking the time.

CLEMMENSEN: Yes, thank you.

Related links:

- Karina Clemmensen’s faculty page

- Clemmensen’s paper in Science

[MUSIC: Meshell Ndegecello “Dead End” from Weather (Naïve records 2011)]

The Future of Robots

Charli, the humanoid robot (photo: Spectrum Magazine)

CURWOOD: Our humanoid friends and help-mates have just celebrated National Robotics week - with special events such as a Robot Zoo, and a Robot Block Party though of course we don't imagine the bots are drinking beer or wine. They may be the stuff of science fiction, but robots are now widely used in industry. And more and more they take on such dangerous tasks as defusing bombs or flying aircraft over hostile territory. To get some clues of how robots will interact with just plain folks, Lisa Raffensperger took a trip to Los Angeles. Her story comes to us from the IEEE Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation special, "Life in 2030".

RAFFENSPERGER: You smell the Los Angeles Korean Festival before you see it—billows of smoke rising from enormous grills, skillets of dumplings……fried potato pancakes. This small park in central L.A., for one weekend a year, becomes a fairground. Vendors sell food, Korean groceries, and makeup. And L.A.’s Korean population—the largest outside Korea—turns out by the thousands. But in one corner of the hubbub is something quite different.

STUDENT 1: I want a leg battery. I want to stick a leg battery in here so we can run longer.

STUDENT 2: So right’s done. You want me to put it in? There’s a specific order, but you gotta go plug, in, base. I got it. That’s the most annoying motor to change.

RAFFENSPERGER: Two of Dennis Hong’s postgrad students take turns working on a five-foot-tall robot—CHARLI [for Cognitive Humanoid Autonomous Robot with Learning Intelligence], who you’ll meet properly a little later on. They’re getting him ready for his big stage act later this afternoon. His white chest plate is removed, exposing his CPU, or central processing unit, the hardware you can think of as the brain of the robot. He has white arms and a smallish egg-shaped plastic head with a black faceplate. But apart from those, he looks like a contraption from an advanced erector set—all gears, motors, and metal beams.

CHARLI was America’s first true full-size humanoid when he was created back in 2010. Compared to bots like Honda’s Asimo, CHARLI’s strength is that he’s sort of the cheap-and-cheerful type—he weighs only about 30 pounds, and he’s designed to be one of the cheapest humanoids out there.

He’s also, as it turns out, the world soccer champion among robots. Bryce Lee, a Ph.D. student in Hong’s lab, explains.

LEE: It’s got a couple of sensors. One is a standard USB webcam that’s in his head that he uses to look around, find ball on the field, find the lines on the field so he can figure out where it is and locate the goals. Then it figures out how it wants to move in order to kick it to score. It’s also got an inertial measurement unit, kind of like your inner ear, a balance sensor that it uses to figure out if its tilted forward a little bit so it will compensate by tilting itself backwards just to stay as balanced as possible during its walk. But when it runs soccer mode, it’s 100 percent autonomous. It’s actually better playing soccer autonomous than it is with us remote-controlling it. We’re pretty bad at that.

RAFFENSPERGER: But CHARLI hasn’t flown all the way to L.A. from the lab’s home at Virginia Tech to play soccer. He’s here to bust a move, to show off his dance steps.

[MUSIC: GANGNAM STYLE]

The Korean pop song “Gangnam Style” had only weeks prior become a global sensation, and just for this occasion, CHARLI has been taught to do its signature dance. There’s only one problem. The night before, instead of busting a move, CHARLI busted a motor. There are already tiny audience members clamoring…

KID: What happened yesterday?

COLEMAN: He died. He started.

KID: Oh.

RAFFENSPERGER: Will he dance today, they all want to know.

MAN: He’s gonna work at 4 o’clock, definitely. Definitely.

RAFFENSPERGER: Since Hong founded the lab in 2004, RoMeLa—the Robotics & Mechanisms Laboratory at Virginia Tech—has moved increasingly toward humanoid robots. That’s no accident, says Hong.

HONG: If a robot needs to live with us in environment designed for humans, then I claim the robot needs to have size and shape of a human. The reason being when you open a door, the door handle is at certain height, because that’s ergonomics—it’s designed for humans. Your step size has a certain height for humans to walk on the steps. So if robot is not humanoid form, it won’t be able to navigate an environment designed for humans.

RAFFENSPERGER: Not all of the team’s projects are humanoids, but two of their biggest are. One is called SAFFIR—for Shipboard Autonomous Firefighting Robot. The bot is being designed now on a [U.S.] Navy grant. The other is THOR, for Tactical Hazardous Operations Robot. That one will be entered into the DARPA Robotics Challenge, what Hong calls the...

HONG: ...biggest, boldest, most expensive, craziest, most-challenging-yet-most-important-in-my-opinion robotics project in the history of humankind.

RAFFENSPERGER: Exactly the kind of burden these humanoid shoulders can bear. At least, that’s what Hong’s betting on.

LEE: Watch out—you don’t want to be too close to the robot! He might kick you.

KID: Oh, yeah, he’s a soccer champion, I remember. I don’t wanna get kicked in the face by a robot.

RAFFENSPERGER: It’s almost go time, and CHARLI is doing his first and only practice run. He’ll be operated by remote control, but still there are myriad things that could go wrong. His feet set wide, he starts with the side-to-side rocking…then some galloping, feet firmly planted…culminating in the lassoing motions of the song’s music video. It’s a hit. It’s gotta be said: The robot’s got rhythm. Now let’s just hope he’s not got stage fright too. The novelty of robots will wear off in coming decades, and some of their entertainment value with it. They might be as familiar as the postman.

HONG: [The year] 2030, for example, you buy something online, and it’s not going to be a brown truck delivering your boxes but probably unmanned aerial vehicles that’s going to drop this package in front of your door.

RAFFENSPERGER: Still, robots will be far too expensive for ordinary domestic use, Hong says.

HONG: Are we going to have humanoid robots walking around in our home? Probably not. You’ll see these expensive robots used where money doesn’t matter. Medical robotics, military robotics—when people’s lives are involved, cost doesn’t matter.

RAFFENSPERGER: And this part is maybe overlooked in our computer-mad culture: Hong says it’s really the nuts and bolts of robots that will hold them back.

HONG: If you look at technology that involves physical systems like cars or anything that needs to move machinery, it doesn’t grow as fast as information technology. We’ve been talking about flying cars since when? Do we have flying cars today? No, we don’t. So by 2030 I believe we’ll have electronics software up to par, but what’s going to be lagging is physical systems.

RAFFENSPERGER: Hong’s group is working on some such mechanisms, taking inspiration from the way humans walk.

HONG: We’re coming up with big departure from the traditional humanoid architecture, developed these new types of actuator that extend and contract like human muscle, they have built in titanium springs for impedance control. This is high-risk, high-payoff project—it’s ridiculously difficult. But if we can succeed, it’s going to be a revolutionary change in how we can build walking robots.

RAFFENSPERGER: It’s CHARLI’s moment in the sun. Dennis Hong walks out and introduces him, and Charli steps forward right on cue.

CHARLI: Hello, everyone. My name is CHARLI, the first autonomous full-size humanoid robot from the United States made by Dr. Dennis Hong at Virginia Tech. Welcome to the 39th Los Angeles Korean Festival. I hope you are having a great time.

RAFFENSPERGER: In Korean, Hong says how CHARLI is a soccer champ but will today be trying something new. Then, CHARLI’s feet spread wide, cue the music, cellphone cameras already in the air.

CHARLI executes every move perfectly, the audience bobbing along in time. The video is plastered on YouTube. You could even call it a vision of the future—but the reality will be much more interesting if Dennis Hong has anything to do with it. I’m Lisa Raffensperger.

CURWOOD: Lisa's story comes to us from the IEEE Spectrum Magazine, National Science Foundation special, "Life in 2030".

Related links:

- Original story on the Spectrum website

- IEEE Spectrum online

Rod Clark Essay - The Ten Minute Brook

A Northern Cardinal (photo: Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: In many parts of the US, winter has worn out its welcome, and as it finally slips away on his Wisconsin farm, writer Rod Clark made a remarkable and fleeting discovery.

The last patches of snow still linger in Rod Clark's Wisconsin meadows (photo: Rod Clark)

Clark: Have I ever told you about the ten minute brook? I myself have seen it only once in its full glory, sparkling and cold as it carved its way through snow and reluctant ice. My dog Morley discovered it, abandoning our path through the woods in sudden pursuit of the unknown. I called him several times, listening for the jingle of his tags in the crisp air. At first there was only the cawing of some refrigerated crow, and then - I heard it. Nothing sings like a brook, in that crystal braid of voices, saying: Listen to me! I am water, clear and crystal, trickling down over moss and stone. So I was thrilled - but also astonished! To the best of my knowledge, there was no brook on my land!

As the last snow melts, pools and streams appear. (photo: Rod Clark)

But then I found Morley lapping at an icy rivulet that had magically appeared on the hillside - and the mystery was solved. Heavy snows in the upper field had melted, and finally the weight of the water had pierced the dam of snow at the edge of the rows and poured into woods below, creating a tiny brook where none had been before. And standing there, I listened carefully, because I knew that in a few minutes, the upper field would be drained, and the song of the brook would be brief. And it was important to listen to this music pouring out of winter into April, because the brook was singing of warmer days to come and all the songs that would follow, like the one I was hearing just then, above the rush of water, as a young cardinal, perched high in the pines began to sing his ruby song of love for any lady cardinal perching in the woods, and all the world to hear.

Rod Clark expects spring flowers in his garden soon (Rod Clark)

Rod Clark's Cambridge Wisconisn farmhouse home (photo Rod Clark)

CURWOOD: Rod Clark lives and writes in Cambridge, Wisconsin. He's the editor and publisher of Rosebud magazine.

Related link:

Rosebud, Rod Clark’s magazine

[MUSIC: Pat Metheny “Spring Ain’t Here” from Letter From Home (Geffeen records 1989)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth. They call it the greenest building in the country.

HAYES: This is a building that functions like an organism, that's to say it has ears, it has eyes, it has a sophisticated nervous system, and it has a brain it functions very much like the Douglas Fir forest functioned that was here 150 years ago.

CURWOOD: Earth Day founder Denis Hayes and his new Bulltt center in Seattle. That's next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: We leave you this week beside trickling water…

[WATERFALL]

CURWOOD: On the east coast of the big island of Hawaii the dramatic Akaka Falls plunge more than 400 feet down into a gorge. But follow a narrow path through the jungle … and you’ll find a much smaller cascade feeding a stream beneath a wooden bridge, sending up a mist of fine droplets. Toby Mountain recorded this soothing scene for his CD, A Week in Hawaii.

[AUDIO: Waterfall: A Week in Hawaii (Rykodisc 1987)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Alicia Juang, Qainat Khan, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners. The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth