Your Brain On Parasites

Air Date: Week of September 2, 2016

A hairworm parasite exits a cricket (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

Parasites have been on Earth for millions of years, and exist in every type of animal and ecosystem. Writer Kathleen McAuliffe’s recent book, “This Is Your Brain On Parasites”, describes some of the many ways these creatures manipulate their hosts’ behavior to ensure their survival and succesful reproduction. As she explains in conversation with host Steve Curwood, some may even affect human behavior and increase the chance of mental illness and car accidents.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Parasites. They range from microscopic bacteria and viruses to 50 foot long tapeworms. They've been living on us and in us and their other host organisms for millions of years. In her new book, "This is Your Brain on Parasites", author Kathleen McAuliffe describes the numerous links between animals and parasites, how they've co-evolved, and how parasites may actually affect the behavior of humans and other animals. Kathleen McAuliffe joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MCAULIFFE: Pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Your book is really fascinating, and, well, really requires a whole different way of thinking to absorb it. So we're going to go at this sort of one piece at a time. First, talk to me about trematodes and their relationship with ants and why this shows that these parasites can affect the way that animals behave.

MCAULIFFE: Trematode are basically a parasitic worm, but they have three hosts often, or two hosts, different species, and there's a very interesting case of a trematode that when it gets into an ant's brain it instructs the ant to leave its colony at night and climb to the top of a blade of grass, lock on to it, and just hang there overnight. If nothing happens, it goes back down to the colony the next day and he returns the next evening and he will do that again and again until a sheep comes by and happens to eat that blade of grass with the ant attached, and when that happens the parasite gets into the sheep, specifically into its bile duct, which is exactly where it wants to be because that's the only place it can reproduce.

CURWOOD: So, OK, a couple of questions here. Why is the parasite doing this and if it does do this, why isn't it sending the ant away during the daytime? You would think that the sheep eat during the day as well as night.

Toxocara canis (canine roundworm) from a puppy. (Photo: Joel Mills, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

MCAULIFFE: Because if the ant remains attached to the blade of grass during the daytime, it will fry to death in the noonday sun. So that's why it will go back down to the colony and act like a normal ant during the day, but then it returns it night to reattach to that leaf until it gets eaten basically.

CURWOOD: Amazing. So, in another words, the trematode has taken over the life of this ant.

MCAULIFFE: It's hijacked its behavior.

CURWOOD: Now most people are kind of freaked out about parasites, Kathleen, so what made you want to write a whole book about them?

MCAULIFFE: The genesis of the book was an item I came across one day on the web, a brief article about a parasite that gets into the brains of rats, and it actually can turn the animals innate fear of cats into an attraction, and when I say attraction it actually makes the rodent sexually attracted to the scent of cat odor and so needless to say the rodent soon is back in the belly of the cat which is the only place that this parasite can sexually reproduce. And this so blew me away that I thought, can there possibly be more examples of this? It just seemed so wild. And I started asking around and I found out that there's just scores of manipulations every bit as impressive, and they entail ants, they entail fish, they entail crabs, even mammals, so it's a very broad phenomenon.

CURWOOD: Now, there's a fascinating part in your book where you talk about toxoplasmosis, something that people can get from cats and the evidence that quite possibly this exposure to this parasite can change human behavior. Talk to me about this.

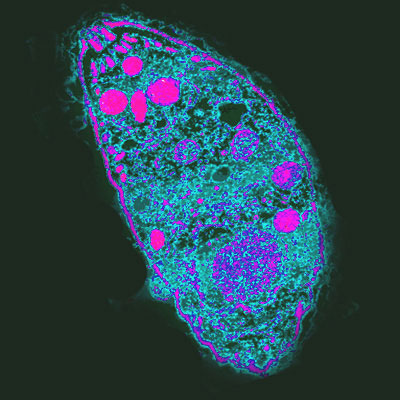

MCAULIFFE: Yes, this cat parasite is the one I mentioned a little bit earlier. I mentioned that there is a parasite that can get into rodents and make them sexually attracted to cats. That is toxoplasma and what happens is after it gets into that cat gut, the cat begins shedding the parasite's eggs in its feces. So we can accidentally be exposed to that when we're change a cat litter box or even sometimes it can happen while you're gardening or if you don't do a really thorough job cleaning vegetables, if you don't get off all the dirt particles, you can be exposed to the parasite that way, and 20 percent of Americans have the parasite in their brain, and a lot of research suggests that in a small percentage of people, we don't know how many, but it can contribute to mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, there's evidence that it increases recklessness and so several studies, independent studies, have shown that people who have the parasite are more likely to be in car crashes. I don't want to terrify people because, remember 20 percent of people are infected and, for example, in the case of schizophrenia 1 percent of the population schizophrenia and the parasite is probably only involved in some percentage of those cases. Some people think as high as 40 percent, others think it is as low as 10 percent or even a few percent, but your risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia is not dramatically elevated simply because you have this parasite in your head.

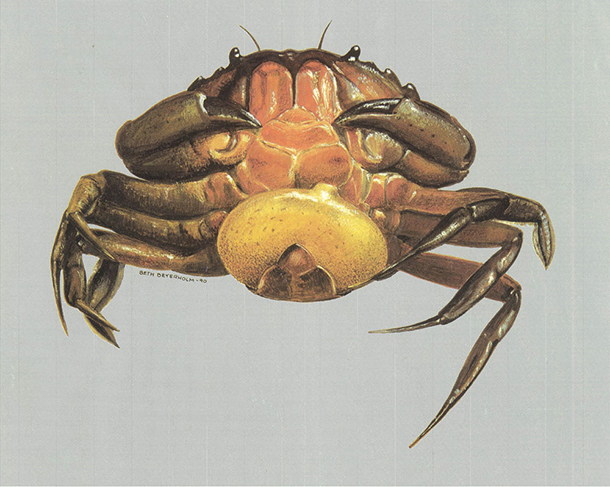

Sacculina carcini, a parasitical barnacle on a female swimming crab from Belgian coastal waters. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

CURWOOD: Car crashes? So being exposed to cat feces could raise the incidence of car crashes?

MCAULIFFE: There are a few studies. I know that one of the best studies which was done in Czechoslovakia involved many thousands of participants, and it was a very good study because it was longitudinal. So they first identified people who tested positive for the parasite, and then they followed them over I believe a five or 10 year period, and they showed that yes indeed, the people who had the parasite we're more likely to go on to be involved in car crashes, especially when they were the party at fault.

CURWOOD: And what kind of numbers did they get regarding these traffic accidents?

MCAULIFFE: The people who tested positive for the parasite were 2.7 times more likely to be in a car crash especially crashes where they were at fault.

CURWOOD: Well, that's almost three times as likely. I guess a defense in front of the judge...the cat made me do it.

Kathleen McAuliffe is a science and health writer and has also published articles for The New York Times, Smithsonian, and Atlantic Monthly. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

MCAULIFFE: Nobody's yet used that defense but interestingly enough Stanford Law School actually held a conference to discuss the question of whether toxoplasma could constitute a defense for criminal behavior. The lawyers ultimately decided that the science is not far enough advanced to be used for that purpose, however, they said in capital punishment cases they might actually try to use the infection during sentencing time as a mitigating factor, because apparently in capital punishment cases because basically you know you may pay for a heinous crime with your life, they are not quite as stringent about the kind of evidence that they'll allow to be introduced into consideration.

CURWOOD: Kathleen, how surprised have you been to learn that parasites seemed to have an effect on human behavior in certain cases?

MCAULIFFE: Initially, when I first heard about it, I was very surprised. However, when you understand how some of these parasites work, it isn't so surprising. So, take for example, the parasite toxoplasma. When it gets inside our brains, the neurons it invades, it will crank up their production of dopamine, which is one of our own neurotransmitters. The protozoan itself has genes that allow it to do that, but it does do some things are just so wild and I have no idea how it pulls it off. For example, the same parasite goes into the testicles. It cranks up testosterone production. It causes the rodents to become overly confident, super cocky. That makes them also at greater risk of being caught by a cat. The same parasite can also cause female rats to produce excess progesterone and it has the same effect on them. They become very much emboldened, and nobody knows how they do that. So there's certainly many routes by which this parasite can change behavior. It also just kind of randomly lands often in the brain and if the parasite becomes clustered in certain locations, you can understand why it might, for example, affect your judgement of risk or why it might affect your risk of getting a disease like schizophrenia. If the parasite is sort of randomly scattered, randomly dispersed across the brain, probably you're not going to get many adverse effects, but if it clusters in specific regions, it is easy to comprehend how it might be causing trouble.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about how the parasite that causes malaria causes humans to perpetuate its nefarious mission.

MCAULIFFE: One of the things it does when it infects a person is it introduces an anticoagulant, it's sort of like a blood thinner. So when other insects then feed on that person they can suck more infected blood out of them, and then these little flying syringes can go and infect many more people. Another thing that the parasite does is it, when it gets into a person, it changes their odor; it may actually amplify our scent, and that means that more insects and uninfected insects will then be attracted to the body of an infected person and they will feed on them and then just go spread the parasite to more and more people.

CURWOOD: Kathleen, what kind of stories of been done that demonstrate that the malaria parasite can change human odor?

Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite that infects cats and other mammals, including people. (Photo: AJ Cann, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

MCAULIFFE: There was a very interesting study done in Kenya where they actually put children in tents, separate tents, and they have children who had malaria at a transmissible stage of infection in one tent, and they would have children who were infected but the parasite was not yet at a transmissible stage, and then they had children who were completely uninfected. I wanted to say that all these children were actually protected from being bitten, but they basically released insects into these tents to see if they favored one child over another, and what they discovered is that these insects and they're all uninfected mosquitoes, had a strong preference for the kids that had malaria at a transmissible stage.

CURWOOD: What's your favorite parasite and why?

MCAULIFFE: I think my favorite parasite has to be a parasitic barnacle. Suspend any notions you have about how barnacles look or behave. This barnacle basically injects a clump of its cells into a crab and it just overtakes its whole body. The closest real-life entity to the nightmarish image of a bodysnatcher. This barnacle just all its tissues spread to the inside of the crab and it even sterilizes the crab and then from that moment on, the crab lives and exists solely to nourish the parasite and it will even, when the parasites babies are ready to be born, it will go into deeper water, it will bob up and down and release them send them on their way. So basically, it's a robo-crab.

CURWOOD: Wow, a zombie huh?

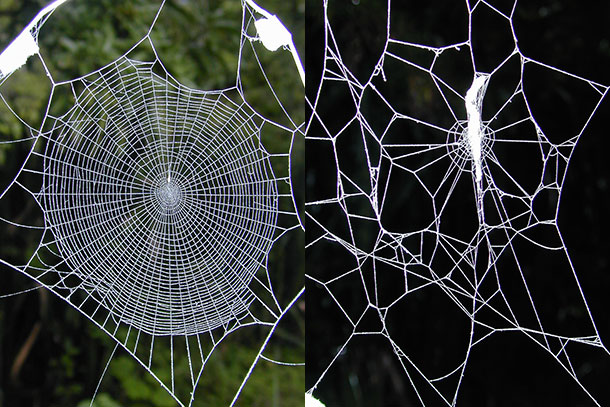

The normal spiderweb on the left contrasts with one spun by a spider infected with a parasitic wasp that changes its behavior. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

MCAULIFFE: A zombie crab. The other thing that's important to know about this is lots of these parasitic manipulators are extremely common in nature and they have big ecological implications. So, for example, this parasitic barnacle, they make up 20 percent of all barnacles, and in many parts of the world, these barnacles have colonized huge proportions of crabs. So, for example, in Danish fjords one quarter of the crabs have been colonized by the barnacle. In Hawaii, 50 percent. In many parts of the Mediterranean, 100 percent of the crabs that you see are really a barnacle masquerading as a crab. I call them robo-crabs.

CURWOOD: So those crabs. Are those crabs we eat?

MCAULIFFE: I asked that question to one of the experts because it horrified me to think that one of those crabs might end up on my dinner plate. The parasitic barnacles as I say invades the soft tissues of the crab like a metastatic cancer but then it sterilizes the crab and where the crab would normally grow a brood pouch on its underside, the parasite grows a brood pouch of its own and it’s visible, it’s he only visible portion of the parasite. It's kind of a yellow bladder shaped organ and fisherman look for it, and when they see it, they do not sell those crabs, they just throw them back in the water.

CURWOOD: Yeah, parasites I mean OK, why do we need them? The thought would be that we might just be better off without them if they didn't exist?

A hairworm crawls out of a frog (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

MCAULIFFE: A lot of food chains actually would collapse if it weren't for parasites because parasites are basically taking a lot of animals out of one habitat and plunking them down in another. Just give you an example there's not a parasite that gets into fish brains and it makes the fish go to the surface and rollover, it lowers the anxiety of the fish so that they then get eaten. Well, the vast majority of these fish become parasitized by adulthood and these fish are amongst the most common denizens of California estuaries and actually estuaries in many different parts the world. As are the shorebirds that then swoop down to eat them. So, parasites have a profound impact on food chains. And it's a question that a lot of biologists is, “would the world be the same if it weren't for those parasites?” Because they're incredibly common. The cat parasite I mentioned, toxoplasma, it has infiltrated basically every warm blooded animal on Earth. It's in birds and all mammals, it has even invaded the marine ecosystem, so it's in dolphins, it's in whales, it's in walruses on ice sheets. So these parasites have a profound impact on ecology and the world wouldn't be the same without them, and yes, they cause horrible diseases, but nature would not work the same without them. In fact, a parasitic existence is the most common on the planet.

CURWOOD: Well, we could go into politics on that one, but we won't.

MCAULIFFE: [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: So given that parasites are so widespread and affect both animals and humans, what's the message here to the medical community?

MCAULIFFE: It depends of course on the specific parasitic manipulation we're talking about. In many instances, there should be I think, one of the applications is that doctors should be paying more attention to how to prevent the spread of these diseases. So, for example, toxoplasma, the cat parasite, it is often transmitted to children through sandboxes because sandboxes are a favorite place for cats to bury their feces. So simply covering sandboxes when they're not in use is a very good way to protect against the spread of the parasite. I think there also has to be greater awareness of the risk of getting the parasite from rare meat. Cattle can pick up the parasite from the ground and it actually gets into their flesh, the meat that we eat. So if you like rare meat, it does increase your risk of becoming infected like 50 percent of French people have a parasite because they love their meat so rare and “saignant” is literally “bleeding”. If you are one of those people who likes rare meat, then it's wise to freeze it first and then cook it because when you freeze it you kill the parasite.

Kathleen McAuliffe has received awards and fellowships in recognition of her excellence in science writing. (Photo: courtesy of Kathleen McAuliffe)

So I think really the emphasis has to be on protection, but also a lot of money is being invested in developing vaccines possibly for cats to stop the spread of this disease and a group of researchers are also looking at developing drugs that can route the parasite out of the head and they're looking specifically at drugs used to treat malaria because as it turns out toxoplasma is a close relative of the parasite that causes malaria so they're hoping that some of the drugs are effective against malaria may also be useful in treating toxoplasma.

CURWOOD: Kathleen McAuliffe is author the book "This is Your Brain on Parasites". Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Kathleen.

MCAULIFFE: It was a pleasure.

Links

The Atlantic: “How Your Cat Is Making You Crazy”

CDC: About the parasite toxoplasmosis

CDC: About the parasite toxocariasis

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth