Bayou Restoration Progress

Air Date: Week of April 8, 2016

Louisiana’s wetlands comprise about 40% of the nation’s wetland area, but coastal erosion erases between 25 and 35 square miles of the state’s wetlands per year. (Photo: Ryan Hagerty, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

There are today ambitious plans to rebuild thousands of acres of marshes in the Mississippi Delta, the first line of storm-surge defense for New Orleans and the surrounding communities. But as Paul Kemp, wetlands expert at Louisiana State University explains to host Steve Curwood, there are still questions over the funding, and even if the marsh restoration plans work, the Delta will be far smaller than it used to be.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Over a decade after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans is in many ways a different city, but still not fully protected by levees and rebuilt marshes. There are ambitious plans to restore the wetlands that once buffered the city, but progress is not as fast as it might be. To update our report from a decade ago, we turn to Paul Kemp, who teaches Oceanography and Coastal Science at Louisiana State University. Welcome to Living on Earth.

KEMP: Thank you, Steve, I'm pleased to be here.

CURWOOD: Now in our earlier piece, we spoke with a biologist about the Caernarvon freshwater diversion project. What's the status of this project today?

KEMP: Well, it's our oldest operating artificial river diversion and it's been now operating since 1991.

CURWOOD: And what is it designed to do exactly?

KEMP: Well, the Mississippi River built the Mississippi River delta. It spread out and delivered water across hundreds of miles of coast through many channels called distributaries. It's understood that if we’re going to have this delta survive with the kind of sea level rise that we're seeing, we have to recreate those distributaries and that's what Caernarvon is, it's the model for a new artificial distributary system.

Wetlands restoration is an important piece of minimizing the impact of storm surges like Hurricane Katrina. (Photo: Information, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA)

CURWOOD: How successful is the Caernarvon diversion project in terms of rebuilding the wetlands there?

KEMP: Well, its purpose was actually to keep salt water that was moving up into the wetlands, keep it farther out to sea, mostly for the benefit of people growing oysters. It has had a beneficial effect on, on the wetlands also. It's actually building a small delta and in places it's enhancing the productivity of the marsh but it's not really meant as a land building marsh.

CURWOOD: Now, what about other such diversion projects. How successful are they proving?

KEMP: We have only three artificial diversions operating right now. Caernarvon as I said is the oldest. There's another one on the other side of the river that's about the same size called Davis pond, and it's been around since the early 2000s. And then we have the West Bay diversion, and so we only have really three of these diversions in operation.

CURWOOD: So there's a major overarching plan. It's a 50-year plan for $50 billion to rebuild as much as some 33,000 acres of wetlands marshland. What's been achieved so far if anything with that?

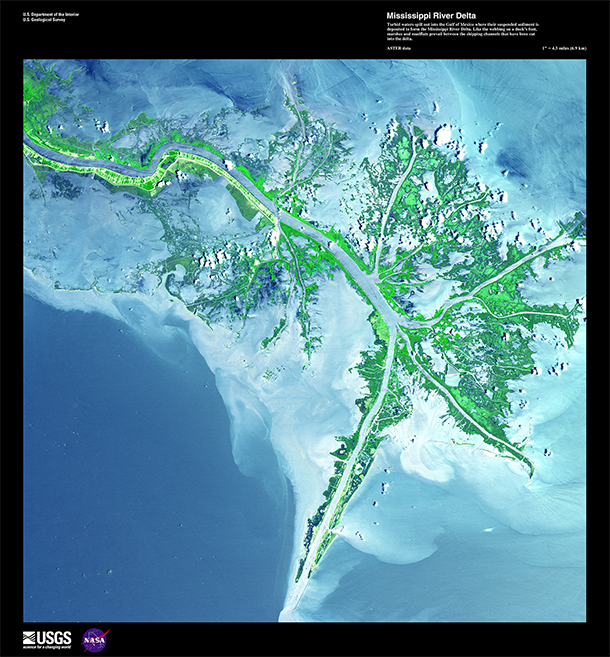

The Mississippi River Delta played a vital role in shaping much of Southern Louisiana over thousands of years. (Photo: ASTER data (direct), Wikimedia Commons)

KEMP: Well I mean a lot has been achieved. I mean land loss continues of course because a lot of what pushes land loss is actually the sinking of the Delta and the rising of sea level which is a global phenomenon, but we are now getting close to opening up diversions that are large enough to really reverse loss over substantial areas; the footprint of the delta of the 21st century will be much smaller than it is today, but it will still be a very substantial delta.

CURWOOD: By the way, the West Bay diversion, how's that doing, what's it done in terms of useful amounts of rebuilding land?

KEMP: Well it's done quite a lot. We have seen a tremendous amount of development both below sea level and more of it now above sea level with vegetation beginning to take hold there. What we learned was that you have to protect the the areas that are receiving sediment from waves and that when you do that land building really takes off.

CURWOOD: Paul, all of this is very expensive. As I understand it the penalty portion of the BP Deepwater Horizon settlement was slated to go to restoration, but in the end I understand it was less than some had hoped. How do you feel about that?

KEMP: Well I mean, the plan ...the 50 year plan that you referred to earlier, Steve, this is a $50 billion plan, and so even when we're talking about the billions in terms of the settlement with BP we're still talking about only a fraction of what is needed. There are pressures of course in this time of very tight budgets to try and move some of that funding toward other important purposes - education, health so on in the state - but those are being resisted very strongly. What we have found is that people in the state and actually at the national level have understood that this is something that has to happen for there to continue to be a place for us to live.

CURWOOD: Professor, recently federal government auctioned off a large tranche of oil and gas leases for the gulf. How might that help or hurt the cause of rebuilding the wetlands?

KEMP: Another source of funding that has been identified is actually mineral revenues from the outer continental shelf. There was a law passed several years ago that stated that starting in 2017, a portion of the proceeds from lease sales and royalties that would normally go to the federal government would actually be distributed to the coastal states that are really feeling the impact of that development in terms of losses to the environment, that will provide additional revenue for coastal restoration.

Paul Kemp is a Coastal Oceanographer and Geologist at Louisiana State University. (Photo: courtesy of Paul Kemp)

CURWOOD: So, Paul, ultimately how hopeful are you about all of this looking ahead?

KEMP: I guess it's more my nature to be hopeful. I teach students and they are helpful and I encourage them to be hopeful and to take an active role in restoration and to restore our coastal landscapes. I think there is some reason to be hopeful. As I said we have the advantage of having the Mississippi River, which is a huge land building asset if it is properly managed.

CURWOOD: Paul Kemp is a geologist, marine scientist and wetlands expert at Louisiana State University. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

KEMP: It's been great, Steve.

Links

Proposed oil and gas leases in Louisiana

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth