Monarch Butterflies on the Rebound

Air Date: Week of March 4, 2016

Monarchs cluster tightly, so researchers can estimate the overall population size based on the amount of forest the butterflies cover. (Photo: skeeze, Pixabay public domain)

As recently as the mid 1990s, a billion or more Monarch butterflies fluttered through US and Canadian meadows in the summer and headed to forests in central Mexico in the winter, but habitat loss, pesticides and climate change have endangered their population. Host Steve Curwood discusses a recent survey indicating a rebound in Monarchs with Tierra Curry, Senior Scientist with the Center for Biological Diversity, and learns what the US and Mexico are doing to ensure that the species continues to recover.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. There’s good news for Monarch butterflies which migrate north from forests in Central Mexico in the spring and back south from the US and Canada in the fall. When researchers began tracking the Monarch populations during their stay in Mexico 20 years ago they found that numbers were dwindling, and recently they went so low it seemed the beautiful butterflies were headed for extinction. Habitat loss, illegal logging, and bad weather are all implicated in their decline, but now a new survey of the Monarch wintering grounds in Mexico offers some hope. For more details we called up Tierra Curry, a Senior Scientist with the Center for Biological Diversity. Welcome to Living on Earth.

CURRY: Thank you so much or having me on the show.

CURWOOD: So, how excited are you that Monarch numbers here in North America seem to be going up?

CURRY: I am really relieved, but I'm also very cautious because the reason the numbers are up three times this year was perfect weather, and so I'm hopeful that we'll continue to have good weather, but the Monarchs are so vulnerable to the weather that we need to get their population to a much bigger size so they can be resilient to all the threats they're facing.

CURWOOD: Now, researchers started looking at Monarch colonies back in the '90s. How big were they then?

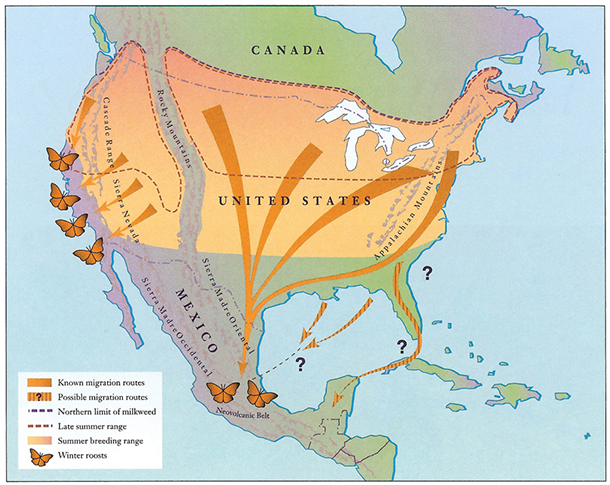

The migration of Monarchs takes several generations to complete. During their time in the US, Monarchs cover 48 states. (Photo: USFWS, public domain)

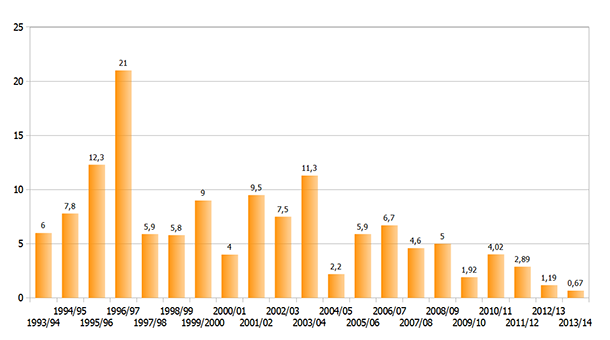

CURRY: You know, back in the mid-90s, they estimate that there were from 700 million to a billion Monarchs, and before people started counting when there were wild prairies and lots of forests in Mexico, there would have been even more Monarchs, so historically there probably were a billion, but then three years ago that number fell down to 25 million. And that caused utter panic because that's so few Monarch butterflies so everyone's breathing a sigh of relief that there's 150 million now, but the Monarchs are so vulnerable to the weather that we need to get their population to a much bigger size.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the territory back when they were a billion. How much forest did they cover?

CURRY: So, monarchs are amazing. They do this multigenerational migration from Canada and the Northern United States at the end of summer all the way down to 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. The monarchs cover 45 acres and so 18 hectares of forest that winter. They cluster really densely on the trees and the trees turn orange because the conditions there are perfect for them to spend the winter. It's not so hot that they wake up and burn off all their fat, and it's not so cold that they freeze. And because the area is so small, they're really vulnerable to bad weather threats. Back in 2002, 500 million Monarchs were killed in a winter storm, and 500 million Monarchs is more Monarchs than we currently have in the whole population.

CURWOOD: How small did the territory get?

Size of overwintering area in hectare of the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) in Mexico 1993/94-2013/14, based on the data of Eduardo Rendón-Salinas and colleagues of World Wildlife Fund-Mexico and the Reserva de la Biosfera Marisposa Monarca (RBMM).

CURRY: So this past winter the Monarchs only covered 10 acres of habitat, but three years ago they didn't even cover a single hectacre, it was only 1.6 acres of Monarchs three years ago, so it's good news that they're back up to 10.

CURWOOD: So this is still a tiny tiny area compared to what the Monarch butterflies have occupied there in the Mexican sanctuaries.

CURRY: It is a tiny area, and a big question scientists are trying to figure out right now is how many monarchs do we need to have as a base level to be resilient to all their threats. So the best numbers that scientists have come up with so far is six hectares of habitat, or 225 million Monarchs as the bottom line number that we need. And so this year, we had perfect weather, we had 150 million Monarchs, it's still under the number that we need and what that indicates that we have to increase the milkweed habitat in the summer in their breeding grounds in the United States and Canada. Scientists estimate that we've lost more than 165 million acres of milkweed, and so far we've only restored about 250,000 acres, and we're still losing one to two million acres a year, so the ball is in the court of the United States to get more milkweed in the ground and to stop the loss of milkweed if we're going to save the Monarchs.

In the winter, Monarchs swarm the skies in central Mexico’s Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve and clump on the branches of oak, fir and pine trees. (Photo: rainasun, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And just to be clear, Monarchs depend on milkweed for breeding, and since this is a multigenerational process, at each stop they need to lay eggs, go through that process, and they can eat other things but they must have milkweed for breeding, if I have that correct.

CURRY: That's right. The Monarch adults nectar on a variety of different flowers, but the caterpillars will only eat milkweed and the milkweed has these toxins in them that give them some predator defense from birds and make them distasteful. So, the Monarch females have to fly around until they find a milkweed and if they don't find a milkweed then they just can't reproduce. But the challenge that is facing the Monarch are really huge right now especially in the United States where we've lost so much milkweed to agricultural changes. Basically, as crops have been genetically modified to be resistant to herbicides and glyphosate in particular, the corn and soybean fields that hosted the Monarchs traditionally have become sort of ecological deserts. So they don't support native pollinators anymore, they don't have milkweed and the other flowers that are important for the Monarch butterfly and that's what has caused the migration to take such a big hit in recent years is the loss of milkweed.

CURWOOD: How has the Mexican government worked to protect the habitat, the forest area there where they overwinter?

Tierra Curry at the Minneapolis Monarch Festival (Photo: courtesy of Tierra Curry)

CURRY: Mexico has been working really hard to protect those forests because Monarchs are really important in Mexico culturally. You know, they go there in the winter, their arrival marks the beginning of the Day of the Dead celebration, some people think that they represent the souls of the departed, but they're really important culturally and historically. They've increased enforcement, they're monitoring, they're working with the local communities to promote sustainable tourism and alternative sources of income for the people, they've made some arrests for the illegal logging that happened in the past year. So I think with everything Mexico is doing it puts the ball even more firmly in the US's court to step up our game and make sure that our summer breeding habitat is protected. And so everyone can make a difference by planting milkweed, but the challenges that it's facing are huge in terms of habitat loss and herbicides and climate change which threatens its US habitat with drought and with heat waves and it threatens the Mexican forest habitat. So we all need to do everything we can and I think it makes to be protected so that there's a comprehensive strategy and funding to make sure that we still have Monarchs for future generations of children to see and revel at.

CURWOOD: Tierra Curry is a Senior Scientist with the Center for Biological Diversity. Thanks, Tierra, for taking the time with us today.

CURRY: Thank you for talking about Monarchs.

Links

Study: Forest Surface Occupied By Monarch Butterfly Hibernation Colonies in December 2014

WWF-Mexico and partners protect Monarchs and their habitat

Monarch Numbers in Mexico Fall to Record Low in 2014

Monarch Joint Venture: federal and state agencies, NGOs, and academic programs save Monarchs

About the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth