Fingerprinting Frackwater

Air Date: Week of July 10, 2015

An aerial view of a wastewater pond located in the Marcellus Shale, Pennsylvania. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

Determining the source of water contamination in the environment is tricky, as many industrial pollutants are similar to naturally occurring chemicals. A recently developed method of “water forensics” could help determine if a frackwater spill is the culprit. Robert Jackson of Stanford University explains this method to Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald and describes why it’s important to pinpoint the source of environmental pollutants.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Now, as he [Allegheny Front’s Reid Frazier] was explaining, pinpointing the precise source of groundwater contamination can be tough. Many fracking chemicals are naturally occurring, or are used in other industries. But a study published a few months ago in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology lays out a new forensic approach to help track down the exact source of fracking water pollution. One of the authors is Robert Jackson, who teaches at Stanford University. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald.

FITZGERALD: So tell me about a little bit about what you’ve done, about your study, and how that's addressing some of these problems.

JACKSON: Well, for a number years now, we've been interested in tracing the chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing fluids and also elements found naturally deep underground that might contaminate groundwater. That contamination could occur through a well that's made improperly or poorly, but it can also happen if wastewater leaks out into the environment. And oil and gas operations in United States generate a trillion gallons of wastewater every year. There's a lot of it.

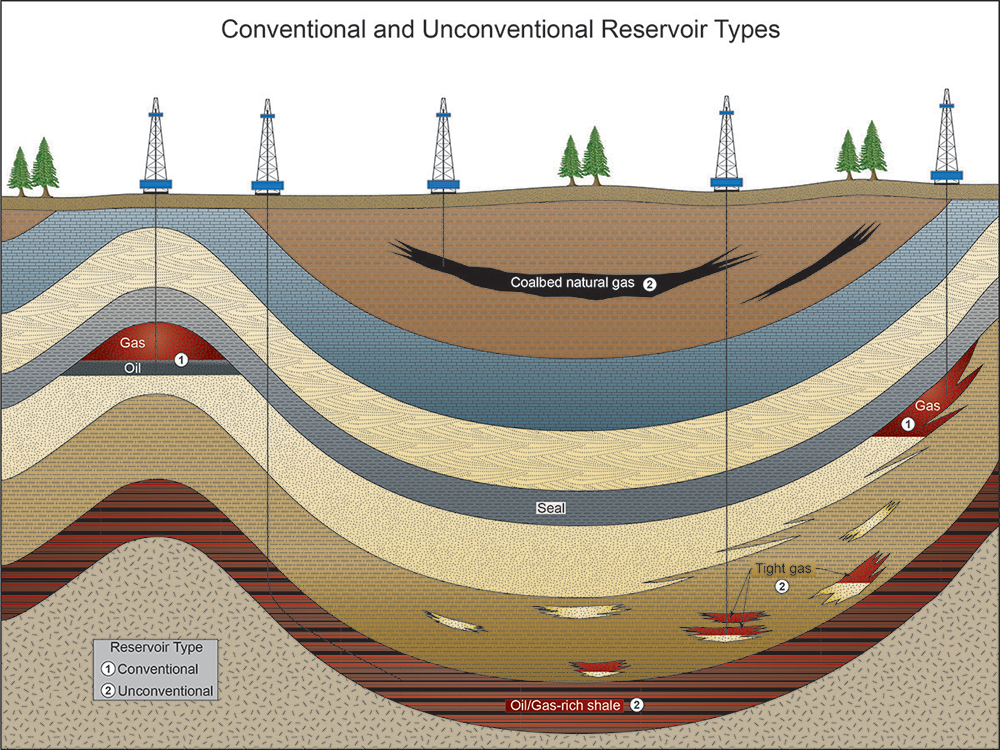

Diagram of location of conventional and unconventional oil and gas reservoirs in ground formations. Fracking (drilling and pumping large quantities of chemical-laden water underground) helps access these reserves. Fracking fluids and water flow back to the surface carrying native chemicals and elements from the surrounding rock and clay formations. These chemicals and element ratios give each fracking wastewater source a specific analytical signature that can be used to identify it in the case of a spill. (Photo: Wyoming State Geological Survey)

FITZGERALD: So tell me a little bit about the work that you're doing, and how you're able to determine whether water has fracking fluids present in it.

JACKSON: Well, in this paper we focused on a handful of elements. Boron, lithium, in particular, but also salts, such as chloride, and even bromide. And we're focusing on these elements because some of them are added into hydraulic fracturing fluids - boron in particular - but all these things are found naturally deep underground. When the company pumps water deep underground to extract the oil and gas, some of that water flows back to the surface. When it does it carries those elements back with them, sometimes in very high concentrations. In the Marcellus [shale region], for instance, the water that comes back out of the well might be 10 times saltier than seawater, and so if that water that is produced out of the oil and gas well leaks onto the surface, then we can use the presence of these elements and their chemical signatures, the isotopes, to identify them.

FITZGERALD: So you call boron and lithium, in particular, tracers. What you mean by tracers?

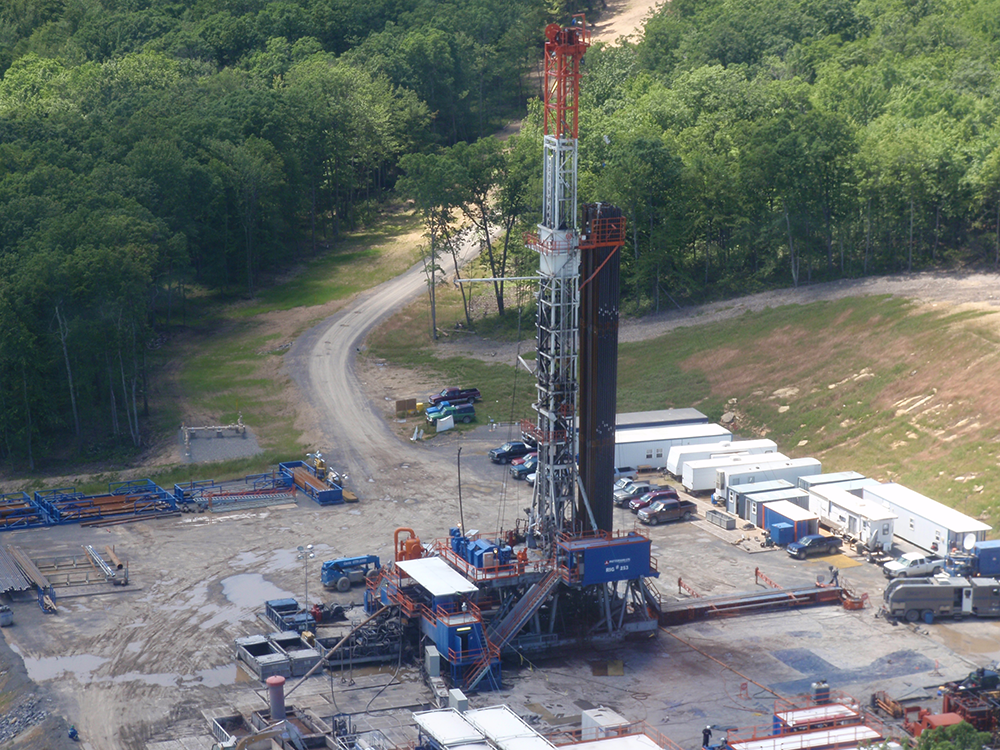

A drilling rig in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. There are over 1.1 million active oil and gas wells in the U.S., and over a trillion tons of fracking wastewater is generated in a year. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

JACKSON: A tracer is a compound that you can use to tell different sources apart. So when I talk about a tracer I'm thinking about something that might be found in different concentrations in different sources. It might be found in one source but not the other at all, or it might have a different chemical signature like its isotopic composition. So these compounds allow us, even at very low concentrations, to identify the source in the environment. So I'll give you an example. A few years ago, in the Monongahela River in Ohio and downstream there was this really big controversy about increases in bromine and other salts in the river water potentially impacting people's drinking water, and there was a lot of discussion about what the source of that was. Was it old coal mines, was it conventional oil and gas wells, or was it the newly hydraulic fracturing wells that were popping up all over the place in the watershed, or at least in the wastewater that was being brought to the watershed?

So this kind of approach allows us to disentangle, to distinguish those kinds of situations. We can separate different waste streams and tag them back to their source.

Truckers ship fracking wastewater around the country for clean-up and processing. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

FITZGERALD: So basically you're looking at the chemical, the presence, the concentration, the isotopic situation with these different compounds and indirectly you’re able to say well this possibly came through fracking chemicals rather than the way it would occur naturally.

JACKSON: That's right. These tracers and many others that we've developed and many other groups around the world have developed allow us to identify the source of contamination in the environment really well.

FITZGERALD: Why would we want to use this approach?

An aerial view of a wastewater treatment plant in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus Shale. (Photo: Prof. Robert Jackson)

JACKSON: We want to be able to keep track of wastewater in the environment. We might want to see if a wastewater treatment facility is working properly. We might want to identify the source of a potential spill, if somebody thinks a spill has happened in their neighborhood or in their stream or river, has it actually happened and if it's happened what caused it? This allows us to go in and identify the sources of contamination in the environment and that's really important and very useful.

FITZGERALD: Professor Jackson, you called this a "forensic approach"...can you explain what you mean?

JACKSON: Well, at a crime scene, investigators will go in and apply a forensic approach. They might gather DNA. They might gather blood types. They might gather hair, and they assemble a set of evidence to assess a probable cause, a probable weapon, even sometimes a probable person. So in science we can talk about forensics in the same way, we can gather and apply a suite of chemical analyses and then apply them to a particular situation and try to figure out what caused the problem.

FITZGERALD: You're fingerprinting fracking wastewater?

Robert Jackson is a Professor of Environmental Earth System Science at Stanford University and co-author on the study “New Tracers Identify Hydraulic Fracturing Fluids and Accidental Releases from Oil and Gas Operations” published in the Journal of Environmental Science & Technology. (Photo: Stanford University)

JACKSON: We are fingerprinting fracking wastewater. It's not the same scale of resolution as a DNA identification. It's not a one in 100 million or one and 1 billion chance. The tools are not that accurate, but they're pretty accurate.

FITZGERALD: In the end, what do you hope comes out of this research?

JACKSON: All of the research that I do in this area has a single purpose in mind. We want to improve things to make things better so we can provide some tools that companies and regulators can use to keep spills from happening, to track wastewater in the environment better and ultimately to make the entire process safer, then I think that's a good reason for doing the work. There's also a basic science component to this we're learning about what's found naturally deep underground so when I get a basic science project and a project with strong relevance today, I'm happy about that.

CURWOOD: Robert Jackson is a co-developer of the frackwater forensic fingerprint technique.

He teaches at Stanford University, and spoke with Living on Earth’s Emmett Fitzgerald.

Links

Duke’s press release on “New Tracers Can Identify Fracking Fluids in the Environment”

Study co-author and Professor Robert Jackson’s Stanford University webpage

Locate over 1.1 million active oil and gas wells, spills and wastewater injection on FracTracker

Difficulty making frackwater clean-up profitable, our piece.

ThinkProgress’ piece on tracking fracking waste

Inappropriate disposal of solid, radioactive frackwaste contaminates water, our story.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth