Climate Risk for Real Estate Values in South Florida

Air Date: Week of July 18, 2014

Flooding during Tropical Storm Andrea in 2013 (Photo: National Weather Service Office in Miami, Florida)

Biologist Phil Stoddard is the mayor of South Miami, a South Florida suburb threatened by rising sea levels. Mayor Stoddard tells host Steve Curwood that municipalities in Florida are doing all they can to prepare for climate change, but he does not think the state government is taking the issue seriously, and the risk to real estate values is considerable.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The latest climate science is sobering when it comes to projected sea level rise in the years ahead. Only days ago, the Obama administration awarded several millions to helping states and tribal regions prepare for the effects of climate instability, including flooding. For Miami, Florida, one of the most affluent cities in America, sea level rise is already a problem. This low-lying region is seeing flooding and local politicians are trying to figure out how best to respond. Philip Stoddard is the Mayor of South Miami, a suburb. He was also trained as a biologist. Welcome to Living on Earth, Mayor Stoddard.

STODDARD: Well, thank you very much. Good to be here.

CURWOOD: So tell us about the situation in south Florida. How is sea level rise affecting the Miami area right now?

STODDARD: Well, what we’re seeing right now is effects on the coastal areas and effects inland, and they’re a little bit different.

So in the coastal areas, South Beach, this is the south end of Miami Beach, gets these king tides particularly in the autumn where on the high tide the water currents are coming in pretty hard, and they force their way in the storm drains and the streets fill up with seawater. And people’s cars rust, and people kayak down the street, and they sell their apartments and move. And so now, Miami Beach is investing a huge amount of money in backflow preventers and pumps and so forth to stop this problem. So that's the coastal problem.

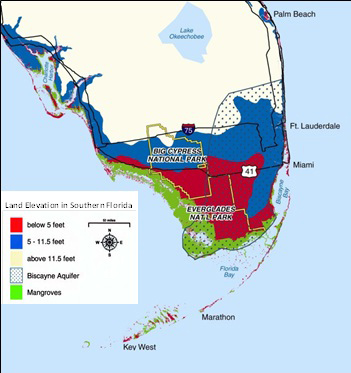

Inland, it's a little bit different. South Florida is extremely flat and so when we get a lot of rain inland it tends not to go anywhere. Now with the sea level gradually creeping up on us it means that there's less downhill for the water to go, and so we tend to see more puddling. We’ve been installing pumps in the inland areas trying to move the water out, but pumping water uphill doesn’t work very well. So the projection is that at some point we’ll no longer be able to pump the water out. There will be too much sea level rise to move the water out, and at that point the inland low-lying areas are just going to flood out.

Storm over Miami Beach (Photo: KatGrigg; Creative Commons 3.0)

CURWOOD: So what are the sea level rise projections in the Miami area, and with that rise in sea level, what do you expect to have in terms of impacts?

STODDARD: The scientists believe now that there's enough heat already stored in the oceans to melt the polar ice sufficiently to put probably 60, 70 feet of water over the planet. That takes out all of South Florida, we don't have any land that’s above 25 feet above sea level. So in the long run, we're all gone, and then the question is how long are you talking here?

CURWOOD: Yeah, how long are you talking here?

STODDARD: I think we'll be looking into -- in about maybe 100, 200 years before we start seeing total inundation on that scale. Now the problem is that we have systems that are very sensitive to sea level, particularly our freshwater supply and our sewage systems that fail at one foot. We've seen now somewhere in the range of eight inches to ten inches in this area since people begin recording, and that has caused some, you know, some problems. We can address those problems in the short term. We can have a good life here for, I don't how long, but certainly the rest of my lifetime I think. Now will my children be able to survive in South Florida for their lifetimes? I very much doubt it.

Land elevation in southern Florida (Photo: EPA)

CURWOOD: Looking at your town, South Miami in particular and the Miami area, how is the advent of global warming affecting things such as housing prices or insurance?

STODDARD: I mean, house prices are going up down here. It’s still a great place to live. What we’re starting to see is pressure on the flood insurance. Our insurance rates are higher than elsewhere in terms of flood insurance, and we have to have flood insurance for mortgages. And the federal government has held off increasing them by one more year. But at some point we're going to have to start paying what someone in FEMA considers to be the realistic risk and our insurance rates are going to go up, and that makes it hard to sell your home.

CURWOOD: What are the odds, do you think, that the Miami area is going to see a crash in real estate prices as people begin to realize that this climate thing—it's not an “if” but a “when”?

STODDARD: Well it’s—we get to debate this one. I mean, here, we’ve gotten out of the solid science into the area of economic speculation, but I think it's inevitable, and what we don't know is when. Ultimately if the water is going to cover us, real estate prices are going to go from high to zero, and the only thing we don't understand exactly is when it's going to happen and what's going to precipitate it.

So my own prediction and I could be wrong on this, but this is my prediction, is that there will be some natural event, a hurricane, a big storm surge—I call these primary disruptors—and one of these primary disruptors is going to shake people, shake their confidence, and some people are going to start moving out. And that point, it's anybody's guess what happens to real estate prices. Once the perception is there, that it’s not a safe place to park your money for real estate, prices drop. Perceptions are very, very important.

CURWOOD: Now what are you doing as the Mayor of South Miami to address this problem?

Low lying and coastal, Miami, Florida is one of the United States’s most vulnerable cities when it comes to sea-level rise (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

STODDARD: Well I think the most important thing we can be doing right now is educating people, just starting the discussions, explaining the science to people in terms they can understand. I don't know that I'm smarter than anybody else, but I sure work hard at trying to understand what's going on, and so I'm able to explain the science to my residents. I’m able to assure them that we are in fact paying attention and the things that we need to be doing, we are doing.

So, we are watching for flooding. We're correcting drainage problems where they occur. We’re looking into the land development codes and what changes have to be made in order to prevent people from creating problems in the near future. I think we’re doing all the right things. We've also got larger scale sustainability issues where Florida has to take a leadership role. We’re not going to solve the problems of flooding by putting solar panels on our houses, but we need to be setting the example; because I mean, if we who have the most to lose don't set an example, who else is going to follow us?

CURWOOD: Now what about the state government there in Florida? What is the state of Florida doing about the threat of climate disruption?

A street in the suburb of South Miami (Photo: Gray Read)

STODDARD: I think the state’s official position involves an ostrich with his head in the sand. I mean we have a governor who was asked about climate change in my presence, and he says, “I’m not a scientist, next question please.” I mean that was a stupid answer quite frankly. Everybody can't be a scientist, but you have to listen to scientists. And you know, you hear people say, “Oh well, the scientists don’t agree.” Well, scientists never agree on everything exactly; that's the process. We debate stuff; we look at evidence. We sort it out. But the state of Florida? No, the state of Florida is in the dark ages.

CURWOOD: So you’re a politician, but you're also a biologist. So as a scientist, what do you think when you hear politicians really ignoring this threat of climate disruption?

STODDARD: [SIGH] I mean, I despair, quite frankly. You know, this is the largest threat that the planet has ever seen. I mean, you know, if we thought for instance that there was a Death Star posed over the Earth, and they said, “We’re going to send a big tube down into your atmosphere and pump it full of carbon dioxide until we cook you guys out of there.” Well, we would mobilize all of the forces we could as a civilization to fight back. “Oh no, you’re not going to cook us out of here.” But yet here we are essentially doing it to ourselves through the fossil fuel industry, and we’ve got people saying that it’s not happening, people who don't want to talk to the scientists, people who really have a vested interest in the destruction of the planet. How can we have these people as leaders? How can we elect them? It boggles the mind.

Mayor Philip Stoddar installs solar panels on his south Florida home, accompanied by his wife, Gray Read and the installer, Danny Upchurch. (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Stoddard)

CURWOOD: Why do you think that local politicians such as yourself are leading the way on climate—addressing climate change in this country, which is clearly a national, international issue?

STODDARD: I think we're leading the way because we see what's about to happen to us. When you see the train coming, and it’s coming directly at you, it's hard to ignore it. You know, when I talk to my geologist colleagues and my hydrologist colleagues, and they say, “Oh, yeah…” I’m not sure I should say this on public radio, but they said essentially, you know, “We’re done for. There's nothing we’re going to do down here.”

Mayor Philip Stoddard (Photo: Courtesy of Philip Stoddard)

I have colleagues who've sold and left, figured they’ll get their money and take off. But most of them, I have to say are sticking it out, and a lot of them are very dedicated to making changes in the medium and short term that will sustain our civilization for longer. And there’s a very, very good reason for doing this even if you sort of despair in the long term, and that is that we can handle problems better if we have time to adapt to them. If something happens very quickly, it creates mayhem because you can't plan. If you can see it coming, then you can start planning, then you can have intelligent solutions to even very, very difficult problems. And that's why it is so critical that we do things now and in the short-term that buy us time, that let us take an orderly approach to the changes that are coming for the planet.

CURWOOD: Philip Stoddard is the Mayor of South Miami. Thanks so much for joining us today.

STODDARD: You're very welcome.

Links

Philip Stoddard is the Mayor of South Miami

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth