Living Downstream

Air Date: Week of May 21, 2010

A farm in Central Illinois, near where Steingraber was raised. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

Biologist Sandra Steingraber wrote about evidence linking cancer with environmental toxics in her book "Living Downstream.” Now she brings her case to the big screen in a new film of the same name. Host Steve Curwood talks with Steingraber about her efforts to make the environment part of the public health discussion.

Transcript

CURWOOD: Recently the journal Pediatrics reported a link between exposure to pesticides and the condition ADHD, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. It seems that almost every week we learn some unsettling bit of news about the effects of chemicals in our food, or water, or air, or the products we use.

Environmental chemicals have long been a concern for author and biologist Sandra Steingraber—particularly those linked to cancer. In a new film based on her groundbreaking book of more than a decade ago, Ms. Steingraber explains why her own cancer diagnosis as a young woman left lingering questions about the disease.

CLIP: I’m one of those people who really does come from a family with a lot of cancer in it. I wasn’t the first in my family to be diagnosed. My aunt went on to die of the same kind of bladder cancer that I had. I have uncles with prostate cancer, colon cancer, but the punch line of my story is that I’m adopted.

CURWOOD: Sandra Steingraber’s book, “Living Downstream”, laid out evidence showing links between environmental toxins and cancer rates in her hometown. Now a new edition of the book and the film of the same name expands the evidence of the relationship between our health and our environment. Sandra Steingraber, welcome to Living on Earth.

STEINGRABER: Thanks Steve.

CURWOOD: Where did you grow up and tell me why you relate the cancer you developed as a young adult to the environment in which you were raised?

STEINGRABER: I grew up right in the middle of the middlest state in America, the second of the three “I” states. Illinois is both and industrial state—we have 30 different industries along the Illinois River valley, and indeed I could look out my back door and see all the smoke stacks of industry, but I could look out the front door and see the farm fields of agriculture—so it’s also a very agricultural state.

An irrigation canal on a farm in Illinois. (Photo: P. Marco Veltri)

And as a young biologist I knew that families have more in common than just chromosomes—that we share an environment. I used some of my background in biology to be able to read the medical literature, and I learned that my particular cancer—bladder cancer—is considered a kind of quintessential environmental cancer.

We actually know more about the environmental contributions to that disease than many others. And so, I was really interested not just in my own cancer, but the cancer rate of the whole area because I’m only a sample size of one. So, yeah, there are it turns out are bladder carcinogens that periodically turn up in my hometown drinking water wells.

CURWOOD: For example?

STEINGRABER: Well, perchloroethylene is one. That’s a solvent that’s used to dry clean clothes, it’s also used in machine shops, which is probably in my hometown how it found its way into the drinking water wells. Trihalomethanes are another group of chemicals that are actually created when we chlorinate water. So I’ve never actually claimed that drinking water with these suspected bladder carcinogens in it as a child is what gave me bladder cancer.

A farm in Central Illinois, near where Steingraber was raised. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

But what I do say, from a human rights point of view, when these chemicals are allowed free access to an environment and trespass their way into our bodies, somebody’s going to get cancer. And that’s the problem.

CURWOOD: What about this gap between what’s known about cancer and the environment and what’s communicated and the way people behave about it? Why does this gap persist?

STEINGRABER: I think there are probably multiple reasons for it. When you go into the doctor’s office you always fill out questionnaires about your family, medical history, and there are no questions that ask you about, you know, where is your water supply compared to the toxic waste landfill? What are you exposed to in your occupation?

We come to believe the source of cancer must lie within the DNA machinery of ourselves. I think that we spent a lot of time in the 1990s searching for cancer genes, but the field of study now called epigenetics reveals that in fact there is another layer of instructions on top of our genome—called the epigenome—to mediate environmental messages streaming in from the outside world.

Sandra Steingraber near her home in Western New York. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

And so the new thinking now within the scientific community about the way genes and environment interact is more like a piano with our genes as the keyboard, if you will, and the environment as the hands of the pianist. You could play Bach or you could play improvisational jazz—it’s the same keyboard, it’s the same DNA but the environmental messages have changed. And so really we need to see cancer as the result of an interaction between genes and the environment.

CURWOOD: At one point you go back to where you grew up in Illinois and you have an interesting conversation with your cousin who’s a farmer. Let’s listen to some of that from your movie, “Living Downstream”:

MOVIE CLIP: We will use a little bit of atrazine usually in the spring, and it’d be nice to not have to use any. It’s expensive. But in production—ag, today—it’s pretty difficult not to. We try very hard to pick our places we use it; we want to keep it out of the water sources. You know, we stay hundreds of feet from any open creeks or surface drains, wells, things like that.

CURWOOD: Your cousin is using atrazine, which is banned actually in the country where the company that makes it is headquartered—Switzerland, much of Europe it is banned—and yet scientists here in the U.S. say there’s not enough damning evidence. First, before I ask you about your cousin, how much evidence does it take to ban a chemical?

STEINGRABER: I don’t think there’s one answer to that. The filmmaker Chanda Chevannes I think made a very wise decision to choose two chemicals to stand in for the hundreds that I kind of review in “Living Downstream”. Atrazine being one and PCBs being another.

And I think it’s a study in contrast; PCBs are one of the handful of chemicals we abolished in the 1970s on the basis of less evidence than we have now for atrazine, and that turns out to have been a very good decision because new research keeps showing us how strong the link is between PCBs and certain kinds of cancer.

And here’s atrazine—the Europeans banned it based on their belief that it’s an inherently unmanageable chemical because it dissolves in rain, it runs into the water, it evaporates finds its way into fog and snowflakes and raindrops. So here’s my cousin, John, one of the most caring people I know, and yet, like so many other farmers he uses a chemical that is one of the most common chemical contaminates of drinking water. I’m sure he is being extremely careful, but the Europeans have decided that no one can be careful enough with atrazine, it’s like opening Pandora’s box, it’s just unmanageable.

And yet, we have the same data available to us, and we reach a different conclusion.

Steingraber on a bank of the Illinois River. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

CURWOOD: It took you, what, four years to make this film you said. And in the course of making it you have a test that revealed some abnormal cells in your own body?

STEINGRABER: I did. I took the camera crew in with me to one of my cystoscopic check ups, in so doing I thought, ‘Well, I’ll pull back the curtain of privacy around this exam, which is so common and familiar to me, but probably most people don’t have a visual image of it,’ and it’s an excellent tool of early detection; it saves lives. It should be me who brings a camera crew into this room, then I got this unexpected result back from that particular exam.

The thing that cancer patients usually do when a test comes back ambiguous is simply pull the curtains of silence around yourself and keep your own counsel. But it’s a kind of high wire act because one wrong word, you know, somebody says something a little too reassuring or they express a little too much worry, it knocks me off the high wire. High wire being I have to be vigilant, I have to advocate for myself, I’m going to need a second opinion, I’m going to need to do some research, but I’m not going to panic, I’m going to hope for the best.

So I’m seeking to make sure that we look as hard as we can for something that I don’t want to find. That’s a very hard psychic place to be and usually you want to have a lot of privacy around you, but we’re in the middle of making a film. And so I knew that I was going to have to talk about these results within the real time of the film and so we did.

Author and ecologist Sandra Steingraber. (Photo: Benjamin Gervais)

CURWOOD: Is there a parallel between this personal uncertainty and that of scientists who are looking, say, for the hard proof about the danger of chemicals who get an ambiguous result that could portend something?

STEINGRABER: So that’s an interesting parallel, actually, I think certainly based on the result of any one study even if it’s statistically significant, we can’t conclude much, and so we’re always in the scientific community looking across in different fields of study—veterinary science, epidemiology, lab bench work—to see whether there’s a kind of state of the evidence that’s beginning to emerge. And the question of our age is, at what time do you decide you have enough data to take action and do something differently?

CURWOOD: What have you done to take action amidst this uncertainty?

STEINGRABER: I’m really interested in taking an upstream approach, a public health approach, to these issues. I’m not interested, for example, in trying to have my children live inside some kind of non-toxic bubble. Moreover, there are many problems that we face that there are no individual solutions for.

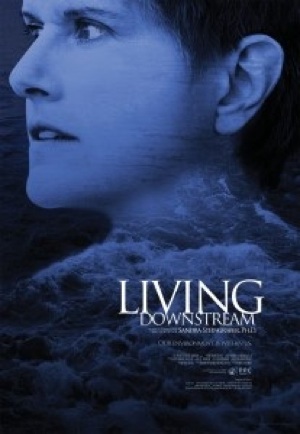

Living Downstream Movie Poster (Courtesy of: The People’s Picture Company)

Most likely my bladder cancer came through an exposure in drinking water. Well, it turns out that most of our exposure to carcinogens in drinking water doesn’t actually come from drinking the water—it comes from bathing and showering. So you can drink all the water from France or Fiji that you want in your bottles, but every time you step in the shower you’re having a very intimate relationship with your public drinking water supply.

So you can’t opt out of the food chain or the water cycle. You know what is in the air, the water and the food rearranges itself and becomes our blood and our flesh and our exhaled breath and our urine. If we don’t want these chemicals in our bodies we can’t have them in the environment.

CURWOOD: Sandra Steingraber is author of “Living Downstream” and the principle player in a film of the same name. Thank you so much.

STEINGRABER: Thank you, Steve.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth