Learn about the Fern

Air Date: Week of March 28, 2008

Willliam Cullina, author of the “Native Ferns Moss and Grasses,” showed reporter Bruce Gellerman native ferns in a botanical garden in Framingham, Massachusetts. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

Ferns usually play second fiddle to wildflowers in the garden but they take center stage in William Collina’s new book “Native Ferns, Moss and Grasses”. Living on Earth host Bruce Gellerman tours the nation’s premier botanical garden for native plants with the author.

Transcript

GELLERMAN: Ferns usual play second fiddle in gardens, but in William Cullina's new book “Native Ferns Moss and Grasses” these emerald plants - subtle and sensuous - take their place front and center.

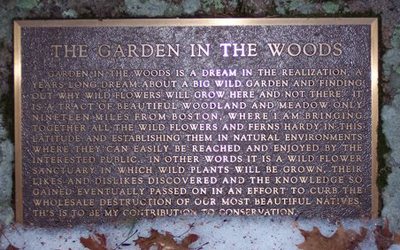

Cullina directs research and development at the New England Wild Flower Society, which runs the Garden in the Woods. 30 miles west of Boston in Framingham, Massachusetts, it's the premier botanical garden in the nation for plants native to America.

[SOUND OF SNOW CRUNCHING UNDER FOOTSTEPS]

A few weeks ago, Bill Cullina took me for a walk along snow-covered paths through the Garden in the Woods in search of native ferns, moss and grasses.

CULLINA: The steps might be kind of slippery, so we can go, you know, take this other path over here.

[SOUND OF WALKING, SNOW CRUNCHING]

GELLERMAN: Now why native ferns, moss and grasses? And how come it’s not mosses?

CULLINA: Well technically it should be mosses. That was something the publishers thought there were too many ss sounds in the title, so they decided to shorten it to moss. But when I first pitched this idea to my editor before I did the woody plant, she said ‘well nobody’s gonna buy a book on green, you know, it’s all green.’ And so I thought a lot, I joke about in the book, you know saying well I’m gonna go around and buy some plastic flowers and stage ‘em around in amongst all the ferns, you know, because you just naturally want to see color. But the more I thought about it and wrote about it and focused my own thinking on the matter, the grasses in the sun and ferns in the shade and mosses, too, really provide the texture and the background on which the wild flowers kind of paint so to speak. You think about a meadow without grasses --it wouldn’t look wild, it wouldn’t really look appropriate. In the same way, in most places in the woods, if you walk around in the woods, most of what you see in the understory, especially here in the Northeast, are ferns. You don’t see huge blazes of wildflowers. You see them sort of scattered around. It’s the ferns that really hold it all together.

Garden in the Woods is a wild plant sanctuary, where ferns and other plants native to America thrive.(Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

CULLINA: Yeah.

[SOUND OF WALKING, SNOW CRUNCHING]

GELLERMAN: Yeah, this is what Simon and Garfunkel would call “a hazy shade of winter.”

CULLINA: [laughs] That’s right, you know we’ve had some years where it stays mild for a long time and a lot of years when we have, you know, more than this snow by this time of year.

[WALKING, HUM OF ENGINE]

CULLINA: The property here is just under 50 acres, and you drove here so you know it’s this little sort of oasis in the middle of the suburban sprawl of Boston.

GELLERMAN: Well there’s a fern right, right there.

CULLINA: Yep, this is a Christmas fern here, so named because it is one of the few truly evergreen ferns that live around here. So most of the ferns will die back down to the ground during the wintertime, but this is really evergreen, and people used to collect these fronds for Christmas decorations, you know just a little bit of green. And people sort of joke if you look--

[WALKING OVER SNOW, STRETCHING]

CULLINA: If you look at these and you pull one of these things off they look kind of like a little stocking, one of these leaflets.

GELLERMAN: Oh yeah.

CULLINA: And so, you know that’s sort of another wives tale that’s why it’s called Christmas fern, but uh...

GELLERMAN: What’s the botanical name?

CULLINA: Polystichum acrostichoides. Most of the ferns have very interesting, sort of tongue-twisting names, and that’s one of them: Polystichum acrostichoides.

GELLERMAN: Give me some other examples of tongue-twistering names.

CULLINA: Well among the ferns -- one of my favorites is Glade fern, the Latin name for it is Diplazium pycnocarpon. And then we’ve got Hay-scented fern, which is Dennstaedtia punctilobula. So you know this -- the Latin names really, especially with ferns, they’re made to describe different features of the plants in Latin. They’re not made to be sort of easy and friendly to pronounce. That’s why common names like glade fern and hay-scented fern are kind of nice for people to have, too.

GELLERMAN: Lady fern.

CULLINA: Lady fern, yeah that’s a nice easy one.

GELLERMAN: Right, right. Now what about Lady fern -- I understand it’s like the most popular here, is that right?

Willliam Cullina wrote “Native Ferns Moss and Grasses.”(Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

GELLERMN: Is it true that Lady ferns can be found in every state but Nebraska?

CULLINA: [laughs] Yeah I bet there’s gonna be somebody out there in Nebraska proving us wrong, but according to the, you know the taxonomic work, yeah that’s basically. Why not Nebraska? Because Nebraska doesn’t have much in the way of the woodland habitat that they need. Most of the other western states have enough in the way of higher elevation habitat somewhere that Lady ferns can grow. There are some ferns like Bracken fern for instance, which is common in the woods around here, probably vying for the most common plant in the world. You can find Bracken fern on just about every continent from the, you know, the rain forests to the mountain tops and you know the boreal forests of Florida and Asia and all over the place. It’s amazing. Part of the advantage of something that’s been around for so long -- it’s been able to colonize just about everywhere, so in parts of Asia people actually collect and eat the fiddleheads of that species, but it’s a highly toxic thing and--

GELLERMAN: A toxic fern?

CULLINA: A toxic fern, yeah. Well, you gotta figure that if you’ve been around for millions of years you’ve figured out how to prevent being eaten, right? So most ferns are loaded with defensive chemicals to prevent them from being eaten. And Bracken fern has got several different kinds of poisons, so I certainly don’t recommend eating it.

GELLERMAN: Really. You know because when I think of ferns, I think of dinosaurs

CULLINA: Yeah.

GELLERMAN: And the ones that were back then, are the same as now?

CULLINA: There’s an amazing discovery, you know just in the last few years they found -- there’s a fern that grows around here called Interrupted fern: Osmunda claytoniana. And it’s a beautiful fern, it’s three foot high, it comes out of the ground it has black-- the spores that it reproduces with are, and these special fronds that are black, so it’s very sculptural when it comes out of the ground. And recently found fossils in Antarctica of all places that are two hundred million years old of this species. So it has remained unchanged for two hundred million years. You think about all the species that have gone extinct in two hundred million years, and this fern, unassuming fern is now, you know, has survived. So, it’s doing something right.

GELLERMAN: Well let’s take a little bit more walk.

[SOUND OF WALKING, SNOW CRUNCHING]

GELLERMAN: Well, I'm looking at this tree, and I was a cub scout and we learned that moss only grows on the North side of the tree. This tree has moss on only one side. Is that the North?

CULLINA: Well there’s two things we’re looking at. We’re looking at the lichens, which are going up.

GELLERMAN: That’s not moss?

CULLINA: No, lichens are different than moss. The moss is on the bottom. What you see on the sides of the tree is a lot of that are lichens. But the mosses are growing down around the base.

GELLERMAN: And the mosses are growing all around the base, so the answer is.

CULLINA: That anywhere it’s moist enough the mosses will grow, so--

GELLERMAN: I wasn’t a very good cub scout, I gotta tell you.

Willliam Cullina, author of the “Native Ferns Moss and Grasses,” showed reporter Bruce Gellerman native ferns in a botanical garden in Framingham, Massachusetts. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

[WALKING, SNOW CRUNCHING]

GELLERMAN: Bill, it would seem to me that you have the perfect job for somebody like you.

CULLINA: I do wake up everyday and think that I’m very fortunate to be doing what I love doing and also this kind of thing -- talking with other people about it -- couldn’t be happier.

GELLERMAN: Bill Cullina is director of research and development for the New England Flower Society. His new book is called “Native Ferns, Moss and Grasses.” Our story was produced with the help of Alexandra Gutierrez.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth