Reach for the Stars

Air Date: Week of October 8, 2004

From the moment nine-year old Neil deGrasse Tyson saw the night sky in New York's Hayden Planetarium, he knew he wanted to be an astrophysicist. Not only did Tyson fulfill his dream, but he eventually became director of the Hayden Planetarium. He talks with Living on Earth host Steve Curwood about his journey, and about why he continues to marvel about the wonders of the universe.

Transcript

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Looking up is something Neil deGrasse Tyson just loves to do. He takes great pleasure in watching “the cosmic real estate,” as he calls it. Stars, nebulae, planets, comets, galaxies --these celestial bodies tease him with their beauty and mysteries--mysteries that he’s working to solve as an astrophysicist and director of New York’s Hayden Planetarium.

As one of a very few African American astrophysicists, Neil Tyson also finds joy in being a role model as he shares his enthusiasm about the nature of the universe. You may have seen him in the recent specials by Nova on PBS called “Origins,” or perhaps you have picked up his autobiography, “The Sky is Not the Limit – Adventures of an Urban Astrophysicist.” Neil Tyson joins me now in our studio.

Now, Neil, you knew from early on in your childhood that you wanted to be an astrophysicist. In fact, you had a defining moment — you were nine years old, you went into the Hayden Planetariun - and, or course, you’re director there now, all these years later - but what happened to you that day?

TYSON: (LAUGHS) That was a defining moment. On that day I was struck by the night sky as I had never before seen it. Having grown up in the Bronx, New York - of course, one of New York City’s five boroughs - I thought I had known what the night sky looked like. It had a dozen stars in it, you know, you can see the moon and the sun – and that was my inventory of the cosmos. It was not until a trip to the Hayden Planetarium at age nine – and the lights dimmed, and the stars came out, and I thought that was kind of entertaining, you know, the nice hoax. I didn’t think it was real, because I knew the night sky – I had seen it from the Bronx, and there were 14 stars. So I was certain it was a hoax until I left the city with the family on a family trip into Pennsylvania, actually, and I looked up, and there was the night sky.

From then to this day – it’s an embarrassing thought, but it’s true nonetheless - that when I look up at the night sky from the world’s finest observing sites I say to myself, it reminds me of the Hayden Planetarium.

CURWOOD: (LAUGHS) But actually the moment, the “ah-ha!” moment, was when you were outside and could really see the sky.

|

|

CURWOOD: Now, why do you suppose that of all the kids from your school class that went to the Hayden Planetarium that day that you’re the one that wound up as an astrophysicist and, in fact, running the planetarium? TYSON: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. Maybe the shape of my neurological receptors was different. But I can tell you this: that every single person I grew up with remembers their first trip to the Hayden Planetarium. I don’t think that’s even unique for the Hayden Planetarium in New York City. Any school trip to a planetarium, you remember that first time your whole life. So it’s not as though that day mattered to me and didn’t matter to others; it mattered to everyone. But, somehow, I was star-struck. CURWOOD: Okay, so you’re a kid in the Bronx. What do the neighbors think of a kid who’s up on the roof… TYSON: (LAUGHS) CURWOOD: That’s where you went to look, right? With binoculars? TYSON: Well, binoculars are not so obvious from afar. But over the years when I saved money from walking dogs, actually, in this apartment complex in which there were many dogs – that’s sort of the urban counterpart to the paper route, is you walked people’s dogs, 50 cents a walk – I bought my first telescope. And I’d haul the telescope to the roof. People would see that and think I had a bazooka or something. Police would come all the time wondering what I was doing. CURWOOD: (LAUGHS) So, what do you say to the cops? Because here’s this African American guy up on the roof with something that look’s like it could be a weapon, and – TYSON: Yeah, plus I had a cord going down to a neighbor to get power to run the clock drive on the telescope, so there’s a wire going down the side of the building. So, this probably looked odd to the police for anyone to be up there. But this is, of course, in the 1960s and 70s, black Americans were not typically thought of as either academic by the establishment, certainly not by the police department – and there I am, looking at the universe. So, the planet Saturn bailed me out every time. (LAUGHS) CURWOOD: Saturn bailed you out? TYSON: Yeah, you just show somebody Saturn through a telescope, they become a puppy. You know, they re-holster their gun and they say, “wow, that’s cool, I want to show my kids!” CURWOOD: So, what is it about the solar system that fascinates you? TYSON: Well it’s not only the solar system, it’s the galaxy and the entire universe. I don’t think I’m unique in my fascination with the cosmos. I don’t twist the arm of editors to have them make cover stories of cosmic discoveries. You look at Time magazine, Newsweek magazine, the major newspapers have science sections – an image comes down from the Hubble telescope, they put it right on the cover. I don’t twist their arm to do that. They know intuitively, if not intellectually, that there’s some deep feeling we all have to try to understand our place in the universe. And this is a feeling that has expressed itself not only across time but through culture. Through the history of human culture you’ve got people wondering what our place is in the universe. For the first time we can now address those questions using the methods and tools of science, which makes today more exciting in that regard than in any previous time. CURWOOD: Okay, I’m going to take you, the scientist, away from science a little bit to plain, old-fashioned emotion. This is the media, right? - TYSON: Sure, okay. CURWOOD: We tell the facts but it’s got to come with feeling. TYSON: All right, all right. CURWOOD: Okay, so I want to do a game of association with you. Is that possible? TYSON: Okay, go for it. Just so you know, I’m generally not strongly driven by emotional thoughts. So I don’t know how this game will go. (LAUGHS) CURWOOD: I guess we’re about to find out. TYSON: (LAUGHS) We’ll find out. CURWOOD: Here’s the game: what word or phrase comes to mind when I mention the following? And we’ll start with an easy one. Now, as I understand it, your favorite planet is Saturn. Saturn. TYSON: Splendor. CURWOOD: Splendor. TYSON: Yes. It’s by far the most beautiful planet of them all. CURWOOD: Really? TYSON: Oh yeah, Saturn, you can’t argue with Saturn. With the rings? Come on now. Other planets have rings, but nothing like Saturn’s rings (LAUGHS). CURWOOD: Jupiter. TYSON: Ah, Jupiter. All I can think of is the comet that slammed into Jupiter back in 1994. A comet slammed into Jupiter. That sight was unforgettable to me, that’s an image I have. It’s a comet that had been minding its own business whose orbit got altered for having come a little too close on one of its fly-bys. And then Jupiter captured it and put it on a collision course and the comet broke into two dozen pieces, and each piece carried the energy of the asteroid that took out the dinosaurs here on earth 65 million years ago. And 24 of them plunged into Jupiter’s atmosphere. CURWOOD: Um, diversion from the game for a moment. What would have happened if that comet had hit the earth? TYSON: There’d be no people left on Earth, just as 65 million years ago there were no dinosaurs left after we had such an impact. But this impact was vastly more devastating, would have been vastly more devastating than even that impact. So, I keep part of my attention and I keep an eye on the vagabonds of the solar system, because one of them will surely show up with our name on it. CURWOOD: I want to come back to that in a little bit, but let’s go ahead with the game now. TYSON: So that means I don’t feel emotion for Jupiter, I just feel the facts about it. I’m sorry, the game isn’t working. We can try a few more. CURWOOD: So far, it’s kind of interesting. To me, anyway. Okay, we’re still in the free association: the Milky Way TYSON: Milky Way. I think of the different cultures and the names they have for it. And my first thought is what they call the Milky Way in China. If I’d practiced this – I think it’s Ying-Hur, which translates into English as “the silver river.” And every time I see the names the various cultures give the Milky Way, they’re all majestic, they’re all poetic, they’re all beautiful. And that’s a testament to the emotions we all feel when we look up and try to name things. We don’t look up and name it 20-syllable words. The biologist sees the fundamental molecule of life and they call it deoxyribonucleic acid. We look up and we say “the silver river” for the Milky Way. (LAUGHS) You know, it’s a different emotion. CURWOOD: The Big Bang theory. TYSON: Big Bang. Once again, in astrophysics we stick to the one-syllable descriptors of things, even important things. Big Bang, you know, I see that as the triumph of 20th century astrophysics. To actually recognize and measure and demonstrate the fact that the universe had a beginning – a beginning. It wasn’t even thought so. Why even have that as a thought? And it’s traceable back to Hubble. Hubble the man, not Hubble the telescope. Hubble the man, after whom the telescope was named, of course. He discovered the universe was expanding in the 1920s. And you run through the math and look at the observations, yesterday the universe was smaller than it was today. Go back a few more days, it was even smaller. Keep going back there’s a point where all the universe began as one little nugget – 14 billion years ago. I think that’s one of the most amazing stories that has emerged from modern science. And not enough people have come to feel that and appreciate what a triumph that is, no longer having to resort to the mythologies of cultures past because we have the methods and tools of science to address these problems. CURWOOD: But, of course, science always raises a question when it answers one. And the obvious one is: what was before the Big Bang? TYSON: We have no idea. (LAUGHS) That’s right, that’s part of the fun of science. Some people are uncomfortable with ignorance. Good scientists have to, in fact, relish in it. In fact, there’s part of a poem by Rainier Marie Rilke. The poem ends, “you must learn to love the questions themselves.” So yeah, right now the next frontier is what was around before the Big Bang. We have some ideas, but nothing grounded in observation or experiment. CURWOOD: Okay, last question in our game here. What word or phrase comes to mind when I mention Pluto? TYSON: Pluto. Overrated as a planet. (LAUGHS) CURWOOD: Overrated as a planet? TYSON: Overrated, overrated. I mean, it was discovered by an American so Americans got all happy about it and, coincidentally, it has the same name as a Disney character – which was first sketched, coincidentally, the same year that Pluto the cosmic object was discovered: 1930. So with Pluto, you know, we think of it as a planet but most people who think that don’t also know that there’s six moons in the solar system bigger than Pluto, including Earth’s moon. And so we don’t start calling our moon a planet, but why not? We ought to if size matters. Well, if size doesn’t matter, let’s look at composition. Pluto is, more than half of its volume is made of ice. If Pluto were where Earth is right now it would grow a tail from the heat of the sun evaporating the ice. Now, what kind of behavior is that for a planet? We have a word for things that have tails in the solar system – we call them comets. In fact, we just recently discovered other objects in the outer solar system that look more like Pluto – Pluto and they look more alike than either of them look like any other planet in the solar system. So we think Pluto has found its family, its family of comets in the outer solar system. I still love it to death but you’ve got to take it in context. CURWOOD: My guest is Neil deGrasse Tyson. He’s director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York, and his book is called “The Sky is Not the Limit – Adventures of an Urban Astrophysicist.” And we’ll resume our conversation in just a moment. You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. [MUSIC: John Williams Conducts John Williams “Parade of the Ewoks” THE STAR WARS TRILOGY (Sony Classical – 1990)] [MUSIC: John Williams Conducts John Williams “The Imperial March” THE STAR WARS TRILOGY (Sony Classical – 1990)] CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. If you’re just tuning in, my guest is Neil deGrasse Tyson. He’s the director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York City and author of “The Sky is Not the Limit: Adventures of an Urban Astrophysicist.” Neil, in your book, which I guess is a memoir of sorts, you write about having an existential crisis with your academic major -- astrophysics. So, I’m wondering if you could read for us from a section here about that time in your life. I think it’s on page 135.

One day after practice we were walking out of the athletic facility when he asked me what I’d been up to lately. I replied, “My problem sets are taking nearly all my time and I barely have time to sleep or go to the bathroom.” Then he asked me what my academic major was, and I told him physics, with a special interest in astrophysics. He paused for a moment, waved his hand in front of my chest, and declared, “Blacks in America do not have the luxury of your intellectual talents being spent on astrophysics.” No wrestling move he had ever put on me was as devastating as those accusatory words. Never before had anyone so casually, yet so succinctly, indicted my life’s ambitions. My wrestling buddy was an economics major and a month earlier had been awarded the Rhodes scholarship to Oxford where, upon graduation, he planned to study innovative economic solutions to assist impoverished urban communities. I knew in my mind that I was doing the right thing with my life – whatever the right thing meant – but I knew in my heart that he was right. And until I could resolve this inner conflict, I would forever carry a level of suppressed guilt for pursuing my esoteric interests in the universe. CURWOOD: Now what was the ethnic background of this gentleman? TYSON: He was black. American black, straight American black out of a city, you know, a big city. So I couldn’t just cite that he didn’t understand my situation. If he were white I could say he just doesn’t know. But we had such common profiles, right on through being the college athletes. And his comment was so simple and so real that I was just devastated. I was devastated. And it took me ten years to dig out of that hole that he put me in. CURWOOD: So how did you resolve this? TYSON: Well I didn’t. I mean, yes, I went on to graduate school – CURWOOD: Yeah – TYSON: But again, I was carrying this guilt, wondering whether I could ever fully and deeply justify my interests. And let me comment that my graduating class that was at Harvard, of 132 black graduates only two went on for advanced academic degrees, myself included. The rest went on to professional degrees – law school, medical school, went into business, that sort of thing. So if you want to ask, you know, who’s doing good, if you go on to a professional degree you make much more money, you become economically upwardly mobile much sooner. And there I was trying to get a PhD for the next six, seven years of my life, earning practically minimum wage doing it. So it took ten years. And it was not until I was in graduate school - Columbia University – there was an explosion on the sun and Fox News called our department. And they would usually send public inquiry to me because they knew I had some appreciation for public curiosity. And I spoke with the weather guy because they always do all the science things with the weather guy. And the weather guy said “There’s this explosion on the sun, should we be worried?” And I said, “Oh, not to worry. This is a blob of plasma, the sun burps these up every now and then and occasionally one heads towards Earth. And it’s charged particles, they’ll see Earth’s magnetic field, they’ll spiral down and collide with our atmosphere, render it aglow. You’ll have a beautiful display of the Northern Lights this weekend. Use it as an occasion to go north. And he said, “That’s great, can we get you on the air saying that?” I said, “Fine.” So they sent up the limo, and I ran home and put on my one tie and my one jacket, shaved, and we did the interview in the studio, pre-taped. I went home, called everybody, of course, you know, grandma, mom, dad, sis. There it was on T.V. I’m watching myself, I’m eating dinner and watching myself, kind of like an out-of-body experience. I said, “Was that me? No, I’m me. So who could that be? Well that was me, but I’m here.“ CURWOOD: (LAUGHS) TYSON: (LAUGHS) The first time you’re on T.V. watching it you have to get through this, your brain has to figure that one out. But anyhow, I realize at that moment – this is 1989 – I had never before seen a black person interviewed on television for expertise that had nothing whatever to do with being black. You think about it, you’ve seen blacks – sure, they’re entertainers and actors and athletes – but when you look at people brought on to television as experts, watching myself that was the first time I had ever seen it. The interviewer didn’t ask me, “Well, how do black people feel about this explosion on the sun?” CURWOOD: (LAUGHS) TYSON: “Does the melanin in the skin make any….?” It was not about being black. It was about my expertise. And I realized this is one of the last challenges of race relations, is shaking this stereotype that the black community can’t do anything intellectually challenging. And I realized that if I or anyone else like me were visible doing just that, that that could have a greater force in the future of race relations than any enterprise zone that gets set up in the inner city. And, at that point, I realized this is what I’ve got to keep doing. I can’t turn down these opportunities. Still need to be the scientist but I stand the possibility of becoming vastly more influential than my accuser ever would have been. And I don’t even know what he’s doing now. I looked him up and couldn’t find him. I don’t know what he’s doing. CURWOOD: He’s probably making money. TYSON: (LAUGHS) Probably making money! CURWOOD: Well… TYSON: That’s my long story. But it was transformative for me. CURWOOD: In your book, you say you want to bring the universe down to Earth. And you lament that Hollywood, even the news, distorts science. How best do we achieve scientific literacy in our society? TYSON: A couple of ways. You know, if I had a nickel for every parent who walked up to me and said, “How do I get little Johnny or Jane interested in science?” And one of my – I give them an answer they don’t actually like – I say, get out of their way. CURWOOD: (LAUGHS) TYSON: If you’ve ever been around a kid – you know, a four-year-old, a three-year-old, a six-year-old – they’re into everything! They’re experimenting. They’re playing music with the pots and pans, and they’re pouring milk on the table and throwing things. And what’s the first thing a parent says? “Stop doing that.” “Sit down.” “Be quiet.” “Stop making the noise.” “Clean that up.” And when my daughter – you know, she was two, she poured milk on the table and watched it drip through the eaves of the table separators, and then looked under the table and watched it drip down on the ground. She was doing experiments in fluid dynamics, as far as I saw. (LAUGHS) And I let that continue and, of course, I cleaned up after her. But I think kids are natural – they’re born curious about the world around them, so in that sense they’re born scientists. You just get out of their way. And make sure you take them to museums where they can express this curiosity, and possibly mess up somebody else’s place instead of yours! (LAUGHS) CURWOOD: (LAUGHS) What did your wife say about this, uh – TYSON: I cleaned up, there was not a problem. I made sure to clean up. CURWOOD: (LAUGHS) Now, what should the role of planetariums be in communities? TYSON: I think, you know, there’s no counterpart to planetariums in any of the other sciences. There are no, sort of, “Here’s a physics particle accelerator for you to visit this weekend, Johnny.” You know, the closest you get to this is dinosaur bones on display. You can bring the universe to the public. The universe is photogenic. Like I said, the Hubble brings back the next picture it’s cover story in all the news weeklies. So we have the advantage that not only is the universe photogenic, our vocabulary to describe it is transparent. We don’t use big words. We use simple words that actually have some descriptive value. Spots on the sun? Sun spots. CURWOOD: (CHUCKLES) TYSON: Big red stars? Red giants. Regions of space where light doesn’t come out and you fall and you never come out? Black hole. These are our formal terms for very real astrophysical things. I’d like to believe that the scientific literacy of the public can be pumped, can be enhanced, can be enriched by using the universe as a hook to get people interested in science at all. If you’ve got people that are indifferent to science I don’t believe they can retain that indifference with the slightest encounter with how beautiful the universe is. You just show them that and they’ll say, “I want to learn more.” Look at the chemistry of space. Now we’re looking for life on other planets. You can become an astrochemist, an astrobiologist, a biogeologist, because there’s life thriving deep within the fissures of Earth’s crust. The biologist is no longer separated from the geologist. They must live together in the same room. So, there’s so many frontiers of science represented in the study of the universe that I think, if that can’t hook you, nothing will. And that’s what we’ve got to promote. And that’s the role of the planetariums going forward, I think. CURWOOD: One of the most provocative parts of your book involves your calculations of the odds of getting killed by an asteroid. TYSON: (LAUGHS)

TYSON: These are important and real questions. In fact, I was co-signer of a letter, an open letter sent to Congress and the administration, appealing – even in the midst of all the problems that we now face in the world – appealing to Congress to consider the importance of devoting some resources, national or international resources, to tracking and monitoring the trajectories of asteroids and comets that we already know cross Earth’s orbit. They just happen to cross orbit when we’re not there, at the moment. But if they cross our orbit at all, one day in the future, they may cross the orbit at the same time we’re in that spot and then hit us. So, getting back to the likelihood of that, a very important statistic that is not widely appreciated. Yes, your odds of getting your tombstone saying “killed by an asteroid” are about the same as the one that would say “killed in a plane crash.” The reason why those are the same is because an asteroid, as rare as it would be, is of tremendously high consequence. If an asteroid the size that took out the dinosaurs hits again – or even less, a smaller one than that – it could kill a billion people. Whereas, an airplane crash, annually a couple of hundred people die in airplane crashes. How long would it take airplane crashes to accumulate to kill a billion people? It might take ten million years, 50 million years. Well, once every 50 million years an asteroid kills a billion people. So, when you look over a long enough base of time, the number of people dead from an asteroid would be the same as the number of people dead from an airplane. And that’s why those statistics match. The point of citing them that way is to sensitize the public to the need to do something. I’m not talking about directing billions of dollars to it because it might not happen for another million years. But you don’t want to be stuck. I don’t want to be the laughing stock of the universe, of being a species on Earth that has the intelligence and the technology to do something about it and end up going extinct for having sat on our hands and done nothing. That would just be embarrassing, I think. CURWOOD: Okay. TYSON: So, what do you do if you see one coming our way? If you want to be macho about it you’d detonate it and blow it into smithereens, but that’s not the wisest solution. What you’d want to do is nudge it out of harms way. It’s still out there, but it takes very little energy to just guide something slightly, give it some sideways motion, so that by the time it would have hit Earth it actually misses us completely. And we’ve got workshops with engineers and astrophysicists and orbital dynamicists working on that very problem right now. But it’s not that much money if you want to know which asteroid would pose that risk. Right now, our inventory of Earth-crossing asteroids is woefully incomplete. There could be thousands that we have yet to discover that are headed our way. And not all are large. The small ones actually hit more frequently. Those are the ones we know the least about. So, it’s just an appeal to throw a couple of dollars that way. Insurance companies know this – it’s the - what is it worth to buy insurance for a very rare but high consequence event. CURWOOD: Now you’ve been on a couple of presidential commissions looking at what we should do in space. So, what do you say? From your perspective, what would be the ideal move for the United States – for this planet – to take in terms of space exploration? TYSON: You have a couple hours for this (LAUGHS)? I’ll try to make that brief, but a couple of things. First, there aren’t many agencies, government agencies, that stimulate dreams the way NASA stimulates dreams. In fact, I would say no other agency stimulates dreams at all. And NASA’s the only one that does it, and they do it like it’s nobody’s business. Those dreams are to look up and imagine yourself among the stars. To look up and answer questions that you might have harbored all your life about is there life in the universe? What is it like to walk around on the surface of Mars? What’s it like on the rings of Saturn? NASA is the agency to do that. And I know there are problems in the world – there were problems in the world in the 1960s, we were fighting the Vietnam war, a cold war, it was the height of the civil rights movement. But the Apollo Project, when you poll people as one of the greatest achievements, not simply of Americans but of human beings at all, the Apollo missions to the moon are at the top of that list. We look upon that era as a time when dreams were realized. And that’s what gives you energy to keep living, to try to improve life. That’s what you – that’s food for happy thoughts in this desert of unhappy, this desert of tragedy and problems that we face in the world and the Middle East and the terrorism threats and the like. Occasionally, I need to pause and look up – and look up literally and philosophically. And our future in space does that for me. CURWOOD: Neil deGrasse Tyson is the Frederick P. Rose Director of the Hayden Planetarium and author of “The Sky is Not the Limit – Adventures of an Urban Astrophysicist.” Thank you so much for taking this time with me today. TYSON: It’s been a pleasure. [MUSIC: The Ventures “Fear (Main Title from “One Step Beyond”)” VENTURES IN SPACE (EMI – 1992)] Links

– “The Sky Is Not the Limit” by Neil deGrasse Tyson |

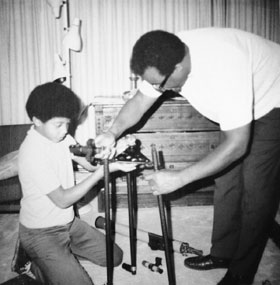

Twelve year old Neil and his father, Cyril deGrasse Tyson, assemble Neil’s first telescope. (Photo courtesy of Tyson Family Archives (1970) Reprinted by permission of Prometheus Books)

Twelve year old Neil and his father, Cyril deGrasse Tyson, assemble Neil’s first telescope. (Photo courtesy of Tyson Family Archives (1970) Reprinted by permission of Prometheus Books)  Neil deGrasse Tyson (Photo courtesy of Patrick Queen© Reprinted by permission of Prometheus Books)

Neil deGrasse Tyson (Photo courtesy of Patrick Queen© Reprinted by permission of Prometheus Books)  At age fifteen, Neil deGrasse Tyson went to Camp Uraniborg in the Mojave Desert in Southern California. In this picture, he stands looking through binoculars next to a large-format astrocamera. (Photo courtesy of Tyson Family Archives (1974) Reprinted by permission of Prometheus Books)

At age fifteen, Neil deGrasse Tyson went to Camp Uraniborg in the Mojave Desert in Southern California. In this picture, he stands looking through binoculars next to a large-format astrocamera. (Photo courtesy of Tyson Family Archives (1974) Reprinted by permission of Prometheus Books)